SEOUL — Three weeks into October, just as the leaves began to change color, a friend and I took an autumn pilgrimage to Seoraksan National Park on the northeastern coast of South Korea, roughly 120 miles from the capital. Disembarking a public bus, we joined hordes of nylon-clad hikers—families with strollers, tourist groups and older folks wielding trekking poles—and streamed into the park, one of the most famous tourist attractions in the country.

I had arrived in South Korea less than two weeks earlier to start my fellowship with the Institute of Current World Affairs. For two years, I will be immersing myself in society here and writing about the country’s culture and politics, with a special focus on its young people. As a newcomer, I’ve been keeping my eyes and ears open, gathering first impressions about a place I’m living in for the first time.

Aside from the natural beauty of the forested hills and mammoth rock formations, two things surprised me about Seoraksan National Park. The first was the convenience and consideration of the park’s development. Restaurants and cafes line the wide, paved path leading to the trailheads; bathrooms are plentiful, including on the trails themselves; and there are even informational displays teaching visitors stretches they can do before and after hikes.

The second surprise was much bigger both symbolically and physically: the Unification Buddha, a 48-foot, 108-ton bronze statue with a glittering urna of amber and jade on its forehead. Completed in 1997 after 10 years and a 3.8 billion won ($2.9 million) investment, the figure was created “in order to achieve national reunification… by combining the hearts of 20 million Buddhist monks as well as 70 million people” in North and South Korea, according to a sign next to its pedestal.

Accustomed to the United States national parks system—which enjoys broad bipartisan support and therefore tends to use politically neutral signage and symbolism—I was surprised to encounter such a strong statement about Korean history, identity and desire on the park’s main thoroughfare. It was a stark reminder that despite the peace I witnessed that morning, my friend and I were in a country still formally at war with its northern neighbor.

Not much later, along a tree-lined trail to a main attraction named Biseondae Rock, our laughter and conversation fell away as we took in another monument, this one a tall, concrete slab with Korean calligraphy running down a black stone in the middle, atop a base of large, gray bricks. It is dedicated to the “Unknown Freedom Fighters” who had battled Chinese soldiers on Seoraksan Mountain during the Korean War in a battle that helped ensure the park and its surrounding areas remained south of the eventual ceasefire line. The structure served as another reminder: Not only is this country still at war but we were standing on an actual battleground.

The synchronism of nature, history and modernity that I observed in Seoraksan was dramatic but not unique within Korea. In Seoul, I have been awed by the thoughtful curation of green space in urban areas, like Haneul Park and Seoul Forest. I have been impressed by modern conveniences and accommodations from subway vending machines that dispense library books to color-coded lights in some parking lots and bathroom stalls that signal empty spaces. And I have felt a similar surprised solemnity about Korean history on observing a monument, a display of battleships in the Han River or a young soldier in camouflage bicycling through a popular neighborhood market.

“If you are aware of [monuments], if you’re looking for them, you’ll see them everywhere,” Quentin Stevens, an urban design researcher at Melbourne’s RMIT University, told me over the phone. Although Seoul does not have an unusually large number of monuments compared to other major cities, Stevens pointed out that the vast majority were erected only in the last 70 years, after the Korean War. The history they commemorate is not much older; many show historical figures and events from the late 19th century on.

By creating such public monuments, Koreans and their government are attempting to settle some of their history and make a statement about who they are and what they stand for. And it makes sense: South Korea has been through a lot in the past century-and-a-half. There is a need to take stock.

In the late 19th century, Korea’s Joseon Dynasty, which had ruled steadily for 500 years, was strongarmed into signing a cooperation agreement with Japan. The peninsula spent the following decades at the center of international struggles. Between 1894 and 1953, it endured two China-Japan wars, 35 years of Japanese colonization, division in two by the Soviet Union and United States and the violence and devastation of the Korean War. While North Koreans went on to suffer repression and poverty under the totalitarian rule of Kim Il-sung and his descendants, South Koreans saw not one, not two, but three successive dictatorships between 1948 and 1988, run by Syngman Rhee, Gen. Park Chung-hee and Gen. Chun Doo-hwan.

From the late 1980s on, South Korea entered a period of steady democratization and truly remarkable economic growth—but it has not been smooth sailing. The Asian financial crisis hit the country hard in the late 1990s, and there have been several flare-ups in tensions with North Korea. South Korean presidents have been routinely investigated and jailed for scandals and corruption. Most notably, perhaps, was Park Geun-hye, impeached in 2017 after South Koreans staged some of the largest protests in the country’s history in response to a corruption scandal. She was later convicted for bribery and coercion.

But against all odds, and in just two generations, the country has transformed from an impoverished battleground into one of the most highly educated and technologically advanced nations in the world, and its 10th-largest economy. While democracy has receded across the globe for 17 years and counting, according to Freedom House, South Korea’s democratic system has been uncommonly resilient. In last year’s presidential election, prosecutor Yoon Suk Yeol’s victory came down to less than 1 percent of the vote, and yet he was still able to take office peacefully and uncontested.

That’s why it can be jarring to run into South Korea’s many monuments. They are a reminder of how different life was not too long ago, how unlikely it is for the country to be what it is now, and how much of the legacy of the past remains unsettled.

There are dozens of statues across the country remembering the women forced into sexual slavery during the Japanese colonial era, for instance—the “comfort women,” as they are still sometimes euphemistically called. The treatment of them and other Korean forced labor victims continues to complicate diplomatic relations between South Korea and Japan.

Although many Americans might see the Korean War as the stuff of history textbooks, the war’s violence and continued division of North and South are far from settled issues, as Seoraksan’s monuments demonstrate. To this day, young men are forced to complete mandatory military service to ensure the state can defend itself against North Korean attacks. Many in Seoul are by now numb to the threat of a nuclear fallout, but last spring, millions were thrown into panic by a mobile phone alert telling them an attack was imminent and they should prepare for evacuation.

This, at least, is one of my first impressions: that South Korea is a dynamic place where even the most unlikely changes are possible. Others who’ve lived in and written about this country have reached similar conclusions. The British journalist Daniel Tudor wrote in his 2012 book Korea: The Impossible Country that “[t]he Korean character does not resign itself in the face of tragedy and misfortune. People believe in their power to overcome almost any situation.” He attributes that steadfastness partly to some of the country’s major belief systems: Buddhism, which encourages continual self-improvement, and Confucianism, which demands the same through a focus on education.

Since arriving, the monuments I’ve seen, the human rights and international relations panels and conferences I’ve attended and the experts I’ve spoken to have confirmed that rebellion and change are an inherent part of what it means to be South Korean.

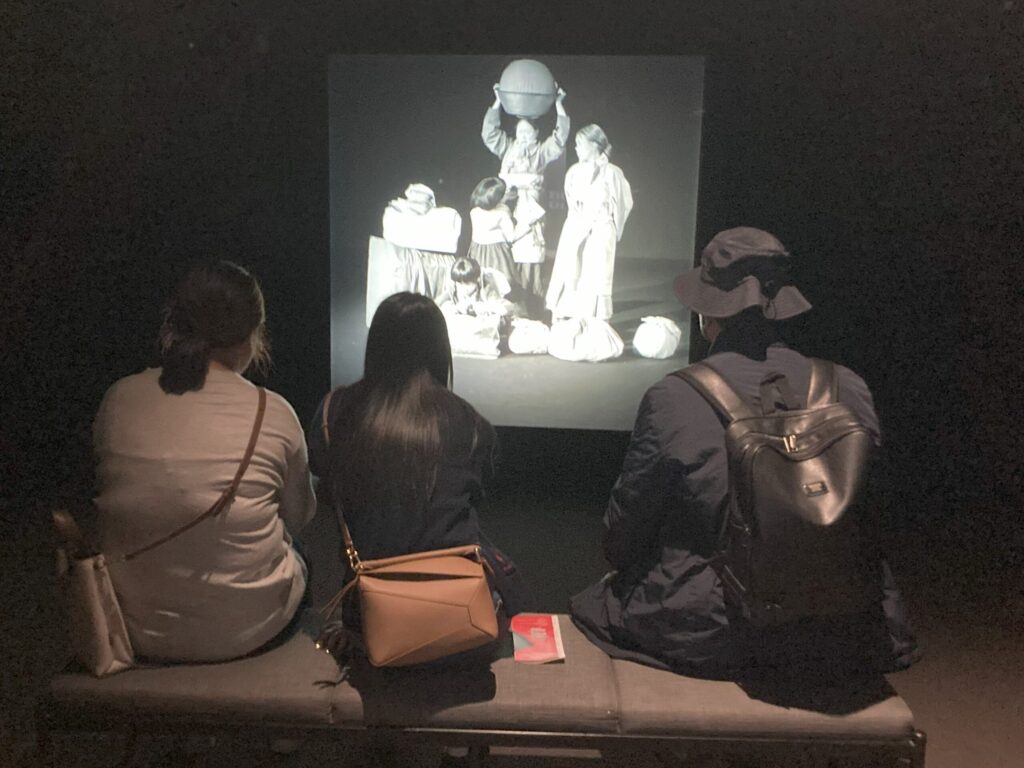

Government institutions, for instance, emphasize Korean tenacity. In the National Museum of Contemporary Korean History, curators tackle those 150 years of history by focusing on the Korean people and the many grassroots resistance movements they have organized. Rather than presenting Koreans as passive actors victimized by foreign agents, they kick off the exhibits by asking, “What kind of nation, what kind of life, have Koreans dreamed of in the chaos of world history?”

Indeed, Stevens, the urban development researcher, tells me that opposition to adversity—and especially opposition to Japanese influence—is an important part of nation-building.

“There are many examples of opposition to the Japanese colonial era as a way of reestablishing a narrative of Korea as an independent nation,” he explained. “There are four different statues of individual independence fighters during colonization, who all died or were captured trying to kill senior Japanese officials. Some of them are even holding grenades or throwing them. I find that unusual because in the West, I’m not used to seeing these kinds of demonstrative, violent acts of opposition in commemorative works.”

Today, the spirit of resistance looks like fervent participation in democracy. Seoul is alive with daily protests; it’s become, as The New York Times put it, “a kind of national pastime.” The last several weeks have seen gatherings to commemorate the victims of last year’s Halloween crowd crush, when the push and pull of hundreds of revelers accidentally caused 159 deaths and dozens of injuries in the central Itaewon district; strikes by subway workers, public school teachers and the largest labor union; demonstrations both for and against the Israeli government; new candlelight protests demanding President Yoon Suk Yeol’s resignation; and surely many more I’ve missed.

But in other moments, I get a very different impression. I have heard a lot from young people about the difficulties they face in their daily lives, and about political issues that concern them: violence against women, privacy violations, mental health stigmatization, debilitating academic pressure and much more. When I ask activists and experts if they see a possibility for things to change, they often say no.

“If anything, it’s getting worse,” one human rights activist told me, speaking of the academic and social pressure to succeed.

“I don’t think anything will change,” a mental health researcher told me. “Not in this generation—maybe in two.”

These are people who care passionately about the issues they work on, and yet they don’t expect to see improvement on them in their lifetimes. Part of their hopelessness about the possibility of change seems to be their belief that South Korean culture itself, not just the political system, would need reform for matters to improve. High school students, for instance, endure crushing social pressure to ace the formidable College Scholastic Ability Test—the CSATs, Korea’s version of the American SATs—a requirement to attend one of the country’s top schools.

Presidential administrations have continually passed reforms of the admissions system, hoping to ease students’ burdens. But the Koreans to whom I’ve spoken have said that it’s the competitiveness of parents and judgmental attitude of society in general that really need reform. Although Confucianism can be credited for South Koreans’ tenacity, some of its principles—such as its directive to improve one’s circumstances through education—also seem to be at the root of many other issues with which young South Koreans now struggle.

It seems there is a rigidity to Korean culture that can’t easily be addressed. An American in the entertainment industry who has been living here for more than a decade told me most Koreans who are bothered by such aspects of their culture, and have the means, would just leave the country altogether. Those who stay will pass it on to the next generation.

When I first met Eunmi Choi, a researcher at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, a major think-tank, in mid-October, she had been speaking on a panel about how diplomats focused on China-Japan-Korea cooperation could pass on their work to the next generation of leaders. The audience in the impressive white hall in central Seoul’s Grand Mercure hotel was full of young people, but Choi, who is in her 40s, was the youngest on the panel. Before long, and with many humble disclaimers about her expertise on the topic, she was politely disagreeing with older panelists’ assertions about young people and their political views.

“When I saw the audience, especially those from the young generation—even though this session was for the young generation—I felt that they couldn’t agree” with what the older panelists were saying, Choi told me a few weeks later in a conference room at the Asan Institute.

She says she often ends up speaking on behalf of younger Koreans because she’s usually the youngest—and the only woman—in rooms full of “old men.” She says she’s able to raise new ideas by drawing on her experience teaching students at Yonsei University and Korea University. “I get the opportunity to say, ‘I’m sorry, but I think maybe the young generation thinks like this.’”

After a month here, I am also getting the impression that young people tend to be very misunderstood by older generations. For one, I have heard many say young South Koreans “don’t care about politics,” but I think that prevalent idea may have something to do with how “politics” is understood and defined here.

South Korean society is usually divided into four generations. The first is Koreans 70 years-old or older, who are generally very conservative and motivated by anti-communist ideologies. The second generation encompasses those in their 50s and 60s who lived through the democracy mobilizations of the 1980s and tend to be more progressive. Then there is an in-between generation of those in their 40s. Finally, the young generation—often called the “MZ generation,” for “Millennial” and “Gen Z”—encompasses everyone under 40.

South Korean politics has been extremely polarized largely because of the strong ideological leanings of older generations. “Ideology,” as Choi explained, often refers to a party or candidate’s stance on international affairs, especially relations with North Korea and Japan. Progressives are generally friendlier toward both countries, while conservatives are more antagonistic. “Politics” typically refers to the pitched battle between the two sides.

South Korea’s young people, by contrast, are more concerned with other issues and therefore don’t separate themselves across those established lines.

“Young generations are not interested in Korean modern history,” Dong-choon Kim, a professor at Seoul’s Sungkonghoe University, told me. “They don’t even know why national division came to Korea initially or why such a socialist, one-man rule was established in North Korea. And it’s not just history. They are not interested in politics in general.” (Kim is my faculty advisor at Sungkonghoe University, which supported my Korean visa application.)

“For young generations, [the Korea they know] is already a democratized country—already a wealthy, relatively economically developed country,” he added. “Their sense of Korean society is quite different from older generations.” Kim believes the younger generation’s lack of interest in history and politics is a postmodern, neoliberal trait. “They are quite sensitive about the gender issue and the environment, but not politics and state and class.”

From what I have observed so far, young people certainly seem hesitant to wade into the ideological debate, not least because it seems unproductive. Those I’ve spoken to said they avoid bringing up politics at work or school, afraid that ideological differences could hurt their prospects for success.

Even when talking about issues that, to me, seem inherently “political,” young people emphasize a desire to stay out of the political fray. At a youth conference on women’s rights in North Korea, for example, one speaker emphasized the need to “depoliticize” the topic to make any progress because otherwise it “may be exploited for political gain in the South Korea scene.” Many in the room hummed and nodded in agreement.

Given the apparent cultural rigidity and political polarization that they face, any hopelessness on the part of young South Koreans would not be surprising. And yet the way they see their country and the world is so different from previous generations that change seems almost inevitable. What kind of change, however, is not yet clear.

Many young people here are clearly dissatisfied with life in their country and have been for a while. In the coming months and years, I hope to address some of the issues they care about so I can better understand how they see South Korea and its place in the world, and what that might mean for its future.

Top photo: Sunset on the Han River at Seoul’s Haneul Park