TROMSØ, Norway — On a blazing day in early August, the long blue channel slicing through dark mountains was sun-blinding. At the side of a shoreline road, under the shade of a slope, I had stopped with my bike for a drink of water. At my feet, bright grass tangled with yellow wildflowers tumbled down a hillside to a white beach lapping translucent water. Save the buzzing of insects and purl of waves, there wasn’t a sound.

“Excuse me, hello!”

Just up the road, a silver-haired man was walking toward me from a parked RV. He waved a tanned arm, revealing a long patch of sweat darkening the armpit of his faded t-shirt.

“This temperature,” he said in a thick Italian accent as he reached me. “Is it normal?”

We were standing 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle and only about 600 miles south of the North Pole. The channel before us was Kaldfjord (“cold fjord”), one of hundreds of straits created where Norway’s northernmost coast splinters into a labyrinth of islands. As we squinted at each other, a gust of cold wind rushed through the mountains, filling our shirts with salty air from the Norwegian Sea and the Arctic Ocean beyond.

This man had never been to Norway before, he told me. He pointed to his dusty van. Expecting frigid temperatures, he had bought extra gas to heat the vehicle at night.

“But this…” he shook his head, gesturing toward the exquisite glimmer before us. “This is Mediterranean.”

I had arrived in the city of Tromsø, five miles west of the fjord, just a week earlier in the midst of an Arctic heat wave. Each 21-hour day climbed into the improbable mid-70s Fahrenheit. On August 5, the local paper’s front page informed me that the coming week would make history—“Record-Varm August”—surpassing a record set only the previous year. Below the headline, a large color spread depicted a remarkably crowded beach at Telegrafbukta, on Tromsø’s southern shore. This man was right; save perhaps the pale complexion of the bathing bodies and distant, unmistakably Norwegian red wooden cabins, the photo could practically have been snapped in Sardinia.

From the moment I had stepped off the plane, the heat was a shock. But I shouldn’t have been so surprised—it was, in a way, why I was here. I had located my ICWA base in this small city near the northern tip of Europe to plant myself in a climate change hotspot. I came here to live full-time in a place changing four times faster than the rest of the planet, and experience it firsthand.

I also came to follow another set of rapid changes as global powers increasingly turn opportunistic eyes to this fast-melting region. Experts call it the “Arctic Paradox”: the same rapid melt that is making this region so vulnerable is also opening it to resource extraction, new shipping routes and other economic development.

Since 2005, when the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment—a first-of-its-kind collaboration of more than 300 scientists, experts and Indigenous representatives—depicted the rate and extent of Arctic melt for the first time, various countries have been jockeying for a piece. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, tensions reached a boiling point. Soon after, the Arctic Council—a forum between eight Arctic states and six Indigenous organizations that has enabled high North collaboration since 1996, including climate science partnerships—was suspended. Most Western countries have also sanctioned scientific collaboration with Russia, so that key global climate models are, for the most part, missing Russian data. For the first time in the era of climate change, half the geographical Arctic has gone dark.

Tromsø houses the headquarters of the Arctic Council, which shakily resumed work in May 2023 with Norway as its chair. Still, many of its projects remain suspended and some experts fear the post-Cold War era of “circumpolar peace” may have reached its end. Last year, Finland and Sweden joined NATO, leaving Russia as the Arctic’s odd-one-out. Moscow is now leaning on Beijing as a new Arctic economic partner with China setting its sights on a future “Polar Silk Road.” On both sides of the Russian border, the North is militarizing at rates not seen since the Cold War.

In the coming years, swift changes in northern climes will be a bellwether for the rest of the world. As the inaugural Peter Bird Martin fellow, I will spend the next two years doing my best to document them. My work will follow an interlocking set of questions. Beyond a latitudinal threshold, how do we define the “Arctic,” and who writes those definitions? As the region emerges as a center of both climate change and global competition, will conflict or cooperation define the next era of polar politics? And, as environmental changes disrupt existing social and ecological systems, what will that mean for the species and people calling this place home?

* * *

Around 5:30 on my first morning in Tromsø, the heavy beat of reggae music startled me awake. I tugged back my blackout curtain and a flood of noontime light spilled through my window. Outside, seagulls swooped and pecked at each other and a flock of teens raced by on skateboards. Just below my open window, a man was unloading equipment from a parked truck, blaring music as he worked. I looked down the steep hill, over multicolored wooden rooftops, to the storefronts of the city center and the ship masts in the harbor below. The day had, it seemed, long since begun.

In the summer months near the top of the world, the Earth’s tilted axis spins toward the sun, washing its highest latitudes in endless day. Winter creates the opposite effect: When the Earth orbits to the other side of our star, the South Pole gets its perpetual day, and the planetary North spends two months in shadow.

In the northern season of sun, I learned, “day” and “night” are flexible terms. Close to midnight, as the sun just started to set, my neighborhood had all the quiet energy of twilit suburbia: Locals in shorts and t-shirts walked dogs, mothers pushed strollers, kids bounced on trampolines in their front yards. “We sleep in the winter,” one resident told me with a shrug. (With her characteristically dry Nordic delivery, I couldn’t tell if she was serious.) Still, it seemed, as long as the sun shines, it’s day. So, by 6 a.m. on that first day, I was out the door to join the city in its waking activity.

Tromsø, a 78,000-person city at 69 degrees North, is known as the “Gateway to the Arctic.” Due to its location along the Gulf Stream, it’s relatively milder than regions at similar latitudes. For that reason, it emerged as a major trade post for European fishers, whalers and trappers in the mid-19th century. In the early 20th century, it was the launching point for historic Arctic and Antarctic expeditions led by the likes of Amundsen and Nansen. (More than 10,000 years ago, Indigenous Sami people were the first to follow reindeer to this region, and have coexisted with Norwegian settlers for the last millennium or so.)

Today, Tromsø remains a vibrant northern capital. It’s a hub of research, fishing, shipping and tourism. The dense rows of historic wooden buildings downtown boast the most bars per capita in Norway, and tourists come to see a myriad of “world’s northernmost”s: the symphony, mosque, stand-up comedy club, 7-Eleven. The University of Tromsø – the Arctic University of Norway (UiT) and Norwegian Polar Institute lead the globe in Arctic research. Diplomats from around the world pass through the Arctic Council Secretariat, the Indigenous Peoples’ Secretariat and an office of the Sami Parliament. And, unlike the rest of northern Norway, Tromsø is growing: The population increased by 10 percent in the last decade.

It may not be a coincidence that the number of people is rising with the temperatures. In August, as southern European cities languished in heat—sections of Spain and Greece both climbed past record-shattering 114 degrees Fahrenheit—typically stormy Tromsø basked in unprecedented summer warmth. Weeks of sun brightened this oft-muted world to technicolor brilliance. Residents, tourists and waterfowl alike flocked by the hundreds to splash in algae-blooming waters, and breezes carried rich scents of grass and saltwater, pine and fish. In the town square, as the (largely pallid) populace strolled with ice cream cones and lounged on park benches, a city health official stood sentinel to distribute free sunscreen.

But just beneath the apparent bliss hummed an undercurrent of concern. Every day in August, my weather app projected a wildfire warning; after an unusually dry year, the woody region was a tinder pending a spark. Later that month, another headline warned of ice loss in the mountains, a full-page spread showing once-perennially white-capped peaks now disturbingly bald. Each year, warming waters are changing ocean circulation patterns, which in turn shift fish populations, threatening local fisheries. (In Norway, seafood is a $10billion-a-year industry, second only to oil.) For those I’ve met who have spent the past decade in Tromsø, the change has been alarming. For lifelong residents, the city was nearly unrecognizable this summer.

* * *

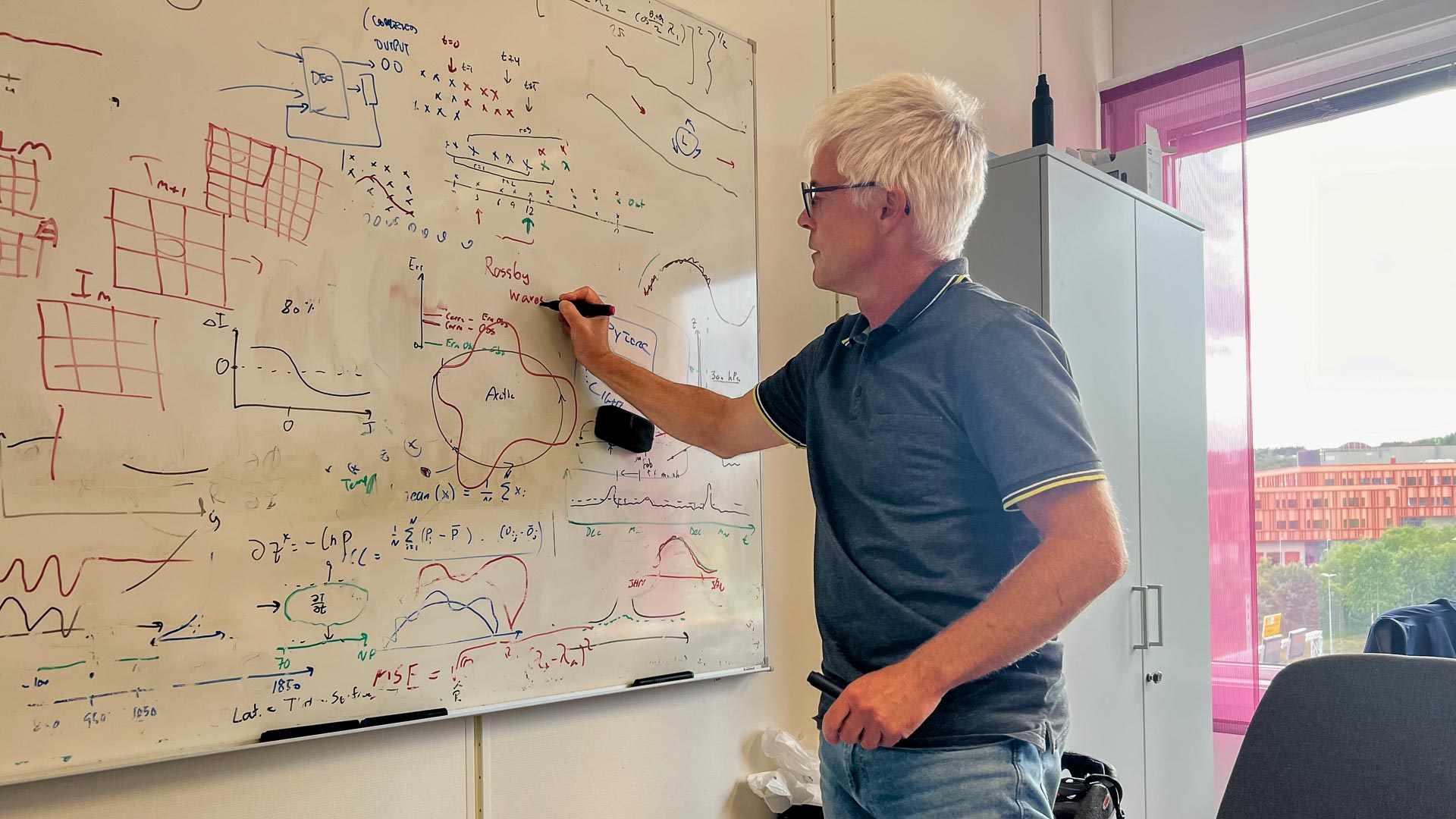

“It is very nice to have a good summer but it is of course also quite scary,” a UiT meteorologist named Rune Graversen told me in a rueful Danish lilt, leaning back in his chair.

I met him on a cool, overcast day in late August in his office in a modern glass building at the world’s northernmost university. In advance of the meeting, Graversen had sent me meteorological records from the past 40 years’ average temperatures in Tromsø, as long as we’ve recorded them. The trend is unmistakable: a jagged graph spiking up and to the right.

Graversen’s research doesn’t specifically concern Tromsø. This warming reflects Arctic changes as a whole, which, in turn, matter to the entire planet. It’s a common phrase in climate science: “What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.” For millions of years, this region has worked as the Earth’s self-cooling mechanism; warm oceans and air travel up here to cool down under the ice before sinking back south. As the ice disappears, the circulation patterns are slowing and shifting, spawning more extreme weather and raising average temperatures around the globe.

Many more consequences are still unknown. Of all the world’s inhabited terrestrial biomes, the Arctic is by far the least understood. These hard-to-access regions are historically understudied and data-poor. In many cases, absent observed data, climate models use borrowed averages from other regions to fill in gaps. But this is just the place where assumptions don’t work: Oceans and atmosphere behave differently here than in mid-planet latitudes. So Arctic climate scientists like Graversen are playing catch-up with the rest of the world.

Graversen researches one such less-understood area: high-altitude Arctic atmospheric circulation. To illustrate, he picked up a red marker and turned to a whiteboard already covered in dense mathematical scrawl. In a tiny white space, he drew the Earth encircled near the top with an undulating crown. It represented “Rossby waves,” large-scale heat transfers that highly influence weather. In the Arctic, they’re slowing down. As warming here outpaces that of mid-latitudes, the pressure differences between the regions decrease, slowing the frequencies of their exchanges. The risk is that weather depends on those exchanges to change. In the future, any extreme weather event could get “locked in” for a frighteningly long period, resulting in catastrophically extended months of drought or deep freeze.

The concept is abstract and Graversen noted my struggle to follow. So he made one point clear: The Arctic is an extremely vulnerable environment. These days, even small changes could trigger catastrophe. That happened in 2007, when “anomalous winds” caused an ice extinction event that permanently destroyed 38 percent of the planet’s sea ice. One trend of warm winds, added to the existing warming effect, hit like an ice-obliterating meteor. All that was lost is unrecoverable.

“You need not a hammer to make a big effect,” he said.

The new era of climate research isn’t about proving whether climate change is happening—it’s about understanding how it’s changing and what consequences that might bring for you and me. Since the collapse of circumpolar scientific partnerships with Russia, that work has become a lot harder.

Graversen is lucky: Weather data relies mostly on satellite observations, and his own work is relatively unaffected. But with each passing day of non-cooperation, we lose data that would help build the overall picture of the Arctic climate—crucial to making predictions that will help plan for what comes next.

* * *

Now, in mid-September, Tromsø is plummeting headfirst toward the dark period. Each night steals another staggering 15 minutes of light so that the sun already sets quite reasonably after 7 p.m. The harbor city has been swiftly restored to its more-typical gloomy glory. As bruised clouds hover low and sudden rains lash windows, locals have traded t-shirts for windbreakers and wool. In just a few months, we’ll plunge into the polar night and I’ll join the city’s commuters on cross-country skis.

Much like the massive research ships that temporarily dock in Tromsø harbor, towering over the city’s modest buildings, it’s tempting to view this city through the lens of its global significance. But it’s still a municipality with its own concerns. Some—a housing crisis, aging infrastructure—are familiar to many urban areas around the world. Others—nuclear submarines docking in the port, disputes about reindeer grazing in yards—are less common.

Part of my work will be debunking misconceptions about the Arctic, a diverse region spanning the top of the planet, home to 4 million people. As this past month made clear, it’s far from only icy tundra. So I plan to also focus my attention locally on this urban area rich with causes and conflicts I have yet to uncover.

To live in the Arctic is to become an unintentional archivist: Every observation captured is a snapshot of a warming planet. But this place is changing more quickly than I can possibly hope to document. That’s the challenge of the climate journalist: To depict flux as it occurs, you learn to see places as processes, grounding the moment in its accelerating march to an uncertain, but undeniably different, future. With each more-truncated day come new observations that leave me wondering, like the bewildered Italian man I met that first sweltering week, “Is this normal?”

I don’t feel qualified to answer. But as Graverson was careful to emphasize, neither do many of the most knowledgeable experts. In the Arctic, normalcy itself is an idea as endangered as perennial sea ice. What happens next is impossible to predict, despite the best efforts of climate and political scientists alike.

I hope to do my best to capture it as it comes.

Top photo: A beach in Kvaløya near Tromsø