PARIS — On the evening of Saturday, May 12, bad news broke. A man in the 2nd arrondissement, a central and touristy area on the city’s Right Bank, assaulted passersby with a knife, killing one and injuring three. It was the latest in a series of terrorist attacks on French soil.

The assailant, 20-year-old Khamzat Azimov, had arrived in France with his parents in the early 2000s, fleeing violence in Chechnya. His family received refugee status in 2004; six years later, his mother gained French citizenship, which enabled him to become naturalized at the age of 13.

In 2016, Azimov—like many other perpetrators of terrorism in France before him—was put on an intelligence watch list known as “Fiche S,” indicating a potential threat to national security. He was flagged as someone susceptible to radicalization, but considered a secondary risk—his entourage, more than any specific actions he had taken, had been the cause for concern. Officials insisted that he otherwise showed no signs of radicalization.

The attack briefly dominated the news cycle, but quickly faded—the death toll was relatively low compared to past violence. Meanwhile, another incident that same evening on the other side of the city curiously did more to capture national attention, exposing some of the complexities of preventing radicalization in contemporary France.

A little before 8 p.m., Maryam Pougetoux, the president of her campus chapter of the student union UNEF, gave an interview on the television channel M6 to discuss protests university students have been organizing for months against a controversial reform to the admissions process. But few seemed interested in what the 19-year-old had to say about the student mobilization. Most attention was focused instead on what she was wearing; in a matter of moments, Pougetoux, who is Muslim and wears a hijab, became the subject of a national controversy that has dominated media coverage for nearly two weeks.

Laurent Bouvet, a political scientist, self-proclaimed public intellectual and cofounder of the Printemps Républicain movement—a group of academics, journalists and former politicians born from the 2015 attacks at Charlie Hebdo, which I discussed in-depth in my January newsletter—took a screenshot of Pougetoux giving her interview. “At UNEF, the [intersection of fights against discrimination] is well underway. The president of the UNEF says so,” he wrote sarcastically, tacitly mocking the notion of “intersectionality”—a theory coined in the United States to describe the way multiple forms of discrimination interact—that he and his fellow ideologues reject. Celine Piña, an essayist, was more direct, accusing Pougetoux of being a pawn of the Muslim Brotherhood, facilitating its “infiltration of student unions.”

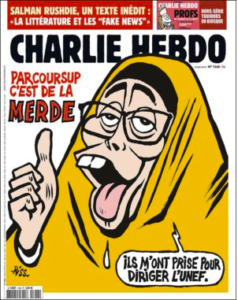

The hashtag #MaryamPougetoux was soon trending on Twitter. Pougetoux had woken up that day as a literature major and student-union president; by the evening, she was a national phenomenon. In the days that followed, she was pictured on the homepage of nearly every national news outlet. The week after, she was caricatured, drooling, on the cover of Charlie Hebdo.

As a reminder, headscarves and all other “ostensible religious signs” are banned in public schools—per a 2004 law based on a certain interpretation of French secularism, or laïcité—but are authorized in universities. Some politicians and intellectuals, including members of the current government, have advocated for expanding the law’s scope to higher education.

Pougetoux, who insisted her hijab has no political significance, expressed shock over the escalation of the incident. The series of events mirrored an episode earlier this year that I detailed in my February newsletter. At the time, figures on the right and left dug into the social-media history of Mennel Ibtissim, a contestant on the TV singing competition “The Voice,” after she performed with her hair covered in a turban. The ensuing hysteria led her to withdraw from the contest despite having awed both the judges and public with her performance.

But while the “Mennel affair,” as it was dubbed, remained mostly limited to the confines of the media, Pougetoux’s case went further, eliciting responses from top government officials across a variety of domains. She wasn’t just a contestant on a singing competition, but a representative of a student union that holds significant symbolism in France. For the likes of Piña and Bouvet, the fact that a Muslim wearing a hijab could preside over UNEF marked a dangerous shift in the union’s politics. In 2013, in contrast, it had advocated to expand the ban on conspicuous religious signs to universities. That perceived slide prompted Marlène Schiappa, the minister for gender equality, to call Pougetoux’s headscarf “proof of religion’s grip” and “a form of promotion of political Islam.”

Seeing everything in black and white

Schiappa’s comments about Pougetoux’s hijab weren’t surprising—after all, much of the opposition to the headscarf in France is based on the assumption that it is a sign of submission to men. Although Muslim women who wear the item routinely refute that assertion, it hasn’t prevented the equivalency between headscarf and female submission from becoming a sort of national dogma. President Emmanuel Macron recently declared that the headscarf is “not compatible with the civility of our country.” Particularly surprising, however, were statements that came from the interior minister, Gérard Collomb, the state official in charge of matters related to the war on terrorism.

In an interview with the well-known TV journalist Jean-Jacques Bourdin, Collomb likened Pougetoux—who was elected by her peers—to the “youth who are attracted to the Islamic State.” The fact that she could even represent the UNEF, he went on, revealed the need to foster a “moderate Islam to oppose this radical Islam.”

But his striking comparison doesn’t hold up to the reality reflected in the profiles of French youth who do radicalize. They often include petty criminals, school dropouts, recent converts to Islam—young people who lack structure, or a cause, and not 19-year-old literature majors engaged in student unions.

Bourdin asked Collomb if that moderate Islam would be “a non-veiled” one. He seemed pleased with his play on words. Collomb paused before concurring: “An Islam that would wear perhaps a sort of veil, but indeed not the full veil” that Pougetoux wears. “My mother, when she went to church, would wear a sort of veil—and perhaps yours did the same,” he said to Bourdin in an implied nod to their common heritage. “And that was a sign, a religious sign, but not a voluntary marker of identity to show that you are different from French society.” That, he concluded, is exactly what Pougetoux did.

Although government officials often describe terrorism in religious terms and focus on Islam’s ostensible aspects—headscarves and burkas, or public prayers—analysts, sociologists and practitioners alike warn against overemphasizing the religious dimension of radicalization. Still, public opinion—echoing the official line, or perhaps inspiring it—remains fixated on the notion that Salafism, a literalist reading of the Quran that seeks to return to Islam’s roots, and imams who preach its teachings, are the roots of extremist visions of Islam that inspire violence.

“Religion is the tree that hides the forest,” an intelligence official who works as a liaison between the Interior and Justice ministries and has decades of experience in the penitentiary system told me in a phone interview. “Average French people, as soon as they hear Allah Akhbar, they think it’s violent—even though, for Muslims in general, it’s something positive,” she said speaking on condition of anonymity. “The public sees only” the religious terms that “become a veneer” for violence, she added. Underneath are young people in search of a mission, an identity.

Elyamine Settoul, a sociologist specializing in criminology and radicalization, agrees. “When we see who ends up going to Syria from France, the social factor is glaring—75 percent come from low-income areas,” he said. “We can’t ignore the role of discrimination against French Muslims,” he went on, noting as an example that all qualifications being equal, job applicants with names presumed to be Muslim or North African are four times less likely to be hired than their white counterparts, according to a much-cited 2015 study. In other statistics, black and Arab young men are stopped 20 times more often than the rest of the population, and are regularly subjected to the French equivalent of stop-and-frisk. And among the more than 36,000 mayors of French “communes,” roughly the equivalent of a township, fewer than 10 are of Arab origin.

Islamist groups and recruiters for the Islamic State “capitalize on that discrimination to influence young people,” Settoul explained, “using it to strengthen their narrative that the Republic failed, that its promises are a lie.” Instead, they offer “a real sense of belonging, a dignified identity.”

But even as scholars and practitioners have insisted on the social or personal drivers of radicalization that often have little to do with religiosity, the government seems fixated on Islam itself. The Interior Ministry official I spoke to complained about that apparent misreading: “I’m sorry, but sometimes when I hear Collomb talk, he says things that seem to undo all of the work we’ve been doing on the ground for years, that we do on a daily basis.” That, the official told me, is likely a function of “political choices of the moment that are made under pressure from public opinion,” at the expense of expertise—or that are often influenced by “mediatized experts who lack necessary knowledge of the field.”

When the interior minister likens a university student to young jihadis, is he genuinely defending a disproven reading of radicalization? Or is he pandering to the nearly half of French people who don’t believe Islam and the Republic can coexist?

The “moderate Islam” to which Collomb referred in his interview with Bourdin is a central element of Macron’s initiative to “reorganize Islam in France,” which he announced in February. That’s not a novel undertaking; governments since the 1980s have endeavored to create structures that would adequately represent France’s diverse Muslim communities. Yet those attempts to foster a sort of national Islam—transforming Islam in France to a centralized Islam of France—have drawn on state links to French Muslims’ countries of origin.

Algeria, for one, is a primary financial backer of the Grande Mosquée in Paris. In 2015, then-President François Hollande signed a deal with the Moroccan monarchy to send French imams to a training institute in Rabat. And the leadership structure of the French Council of the Muslim Faith—a major representative body that then-Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy created in 2003—disproportionately represents individuals and entities tied to Algeria, Morocco, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. According to a 2016 survey, only a third of French Muslims even know what it is, and critics denounce its opacity. The past two generations of French Muslims—who were born and raised in France—have little attachment to those countries.

Macron, for his part, has pledged to break with foreign influence. Although the details remain vague, the idea of creating a national Islam, in culture and theology—by, for example, creating a new generation of imams “made in France,” and limiting foreign financing of mosques in France. But in an apparent departure from that commitment, his government recently invited 300 foreign imams, primarily from Algeria and Morocco, for the month of Ramadan.

For Olivier Roy, a scholar of Islam at the European University Institute in Florence, the focus on Islam’s religious elements—mosques, imams and Salafism—misses the point. “If radicals came from mosques, it would make sense to control mosques, to control the curriculum of what imams preach. But radicals don’t come from mosques,” he told me in a phone interview.

“And we know it. They know it. We have the statistics. It’s absurd,” he added, frustrated, “to think that we can replace a Salafi imam with a ‘moderate’ one to fight jihadism. First, it would be unconstitutional, second, it would violate religious freedom”—which laïcité guarantees—“and third, it’s completely irrelevant.”

Overwhelming frustration

I’ve reflected on these themes during my interviews with French Muslims—often second and third-generation immigrants who are either practicing or come from Muslim households. The majority of the testimonies I’m including here are from women. Curiously, while men are vastly overrepresented among those who join the Islamic State group or wage violence on French soil, the national conversation about Islam as a threat to France has for years centered on Muslim women, and particularly their headscarves.

I’ve taken away an overwhelming sense of frustration with both state officials and the media. Many Muslims I’ve interviewed criticize a disproportionate focus on French Muslims at large in discussions about laïcité, national unity and the fight against radicalization, which they consider stigmatizing and counterproductive. It’s worth considering the way decades of routine op-eds, radio debates and national surveys about Islam’s “compatibility with the Republic” inspire resentment among an entire segment of French citizens who adhere to the faith. When, in a televised interview, President Macron calls the headscarf “not compatible with the civility of our country”—while stressing the need to foster a “moderate, French Islam” to drown out extremists—one wonders what that would actually entail, and what fate would hold for the French Muslims who don’t fit that vision of a national Islam.

I met Linda M., 18, a high school student in the 20th arrondissement, in eastern Paris, at a café not far from where she grew up. She’s soft-spoken and giggly, with fair skin and dark eyes—dimples on her cheeks give her a youthful air, but she’s decisive and articulate. She began wearing a floor-length jilbab when she was 15 and removed it in compliance with the law on religious symbols. (Jilbabs cover the whole body, exposing only her eyes, nose and mouth.) But she clashed with administrators when she wore a long black dress or a thick headband—non-religious items, she insisted, that teachers incorrectly perceived as religious dress because they knew she was Muslim. “They talk about radicalization, about Islamism, about the kids who have gone to Syria, and they say that there’s no space for political symbols at school,” she told me, sipping a hot chocolate. “But there is nothing political about what I wear—it’s a question of my relationship with God, and that’s all.”

She expressed frustration and disillusionment with tired tropes about the veil, and worried that the association between being Muslim—and showing it—and being a potential terrorist would “close doors” for her. She recalled a school trip to London, where she saw police officers wearing hijabs. “It shows that it’s completely normal to wear a headscarf and be a perfectly normal member of society,” she said, exasperated. “Not a threat, just the opposite. Even a police officer!” That, she went on, should disprove theories that women who wear the headscarf are victims, or subject to the demands of the men in their lives. She plans to become a doctor. “Not a single woman in my family wears the veil, and my father isn’t religious,” she added. “They were all surprised when I decided to wear it—it was 100 percent my choice, and the same is true for all of my friends who do the same. In Islam itself, no one has the right to force you to wear the veil.”

Even some of the Muslim girls I’ve interviewed who haven’t been directly affected by the law on religious signs consider society’s demonization of the headscarf alienating. Amal, 18, a high school senior in Vitry-sur-Seine south of Paris, lamented how “easy it has become to attack someone who wears the veil—it has become the most effective way to undermine her credibility.” Her classmate, Aïsha, wondered whether France would ever consider Islam “a religion like the others.” Since terrorism became a national focus in 2015, she told me, “Muslims are considered separate from the population—we’re a collective security question. And when people see a girl with a headscarf on TV, or in the street, they’ll find the easiest way to bring her down.”

Anne Bruneteaux-Dahhan, who is in her 40s and converted to Islam in her 20s, founded Rencontre Avec l’Islam—Encounter Islam—an organization in Saumur, in the Loire Valley, to help chip away at misunderstandings of Islam. She and her colleagues give talks at schools, universities and companies, and organize “open-house” days at mosques.

She wears her hair wrapped up in a turban, which she says rarely elicits strong reactions from her audience. One day, while speaking to a high-school class, she decided to do an experiment. “I asked about the fabric on my hair—what does it make you think? They all said, ‘It’s nice, very pretty.’ What does it make you think of me? They said, ‘Nothing in particular.’” She unraveled the turban and retied it to cover her neck and ears. “And now?” Nearly all of the students’ expressions darkened. “They told me, ‘You look closed-off, conservative, stern.’ I responded, I’m the exact same person—nothing about my face has changed. Why do you see such a difference?”

Bruneteaux-Dahhan was struck by “their bold assertion that I had become a different person—and the fact that they weren’t afraid to say it. It goes beyond what’s rational, it’s so deeply anchored in France.”

Politicizing differences

The knife attack in Paris, the politicization of Pougetoux’s hijab, and Muslim frustration with the media and government’s narratives around Islam are intertwined. They all reflect the complexities of preventing radicalization in contemporary France. When the interior minister likens Pougetoux, a university student, to young jihadis, is he genuinely defending a disproven reading of the reality of radicalization? Or is he pandering to the nearly half of French people who do not believe Islam and the Republic can coexist, according to a February poll? Another recent survey revealed that the majority of the population wildly overestimates the size of the Muslim community, which it places at 31 percent—about four times larger than the estimated reality.

Against that backdrop, it seems that official efforts to prevent radicalization—an undeniable threat that nevertheless remains marginal—can’t be disentangled from the politicized and increasingly vicious debates around Islam in general. The media recalibrating its representation of French Muslims—and considering the societal and political implications of helping turn Bouvet’s snarky Facebook post about Maryam Pougetoux into a national dilemma—would be a good start.

“It might be helpful if the media stopped talking about laïcité all the time, stop presenting Islam as against the Republic,” Linda said, laughing, as if the whole matter had become absurd. “But most of all, they could stop bringing us into debates we didn’t ask for, and discussing our religion, and our interests, without ever consulting us.”

“On the one hand we’re supposed to be French like the rest,” she added. “And on the other, we’re not compatible with the Republic. Isn’t the contradiction clear?”