WENGDING, China — The Wa people weren’t always headhunters. After springing to life from the inside of a gourd, they flourished in the mountains between modern-day China and Myanmar. But according to legend, as they spread, they found their rice did not grow well at higher elevations, so they sought help from their more developed neighbors. The leader of the neighboring tribe was unsurprisingly uninterested in the Wa’s prosperity, so he gave them some sterilized rice seed and sent them on their way. The Wa returned to their land, sowed the seed and waited with disappointing results. They turned to their neighbors for help again.

“You didn’t make an offering of a human head when you planted?” the leader asked. “No wonder nothing grew!” He gave them more seed, this time unboiled and fertile, and sent them home again. Now under the watch of freshly severed heads from neighboring tribes, the healthy seed naturally produced an abundant crop. But intertribal conflict prompted by the violence kept the Wa and smaller tribes at war with one another and more easily managed by their dominant neighbor.

“Your head would make a great trophy,” Yimeng Hongmu tells me as she concludes recounting the Wa legend. “It’s light-skinned and bearded.” Hongmu is a Wa historian who placed top in the entire county on the college entrance exam. I trust her assessment of my head. We are chatting over lunch with Li Zhuqing, a Communist Party official with the Bureau of Culture and Tourism that oversees cultural preservation.

“I’m guessing the neighbors were Han,” Li quips apologetically and the two of them laugh together. Li herself is Han with a round pale face and drawn-on eyebrows like most Chinese women above 25. Hongmu’s teeth shine white against her dark skin.

I came for the mud fight. Every year Cangyuan county attracts over a hundred thousand tourists to the Monihei Festival. The name means “rub you black” and is both a reference to Wa people’s dark skin and their tradition of blessing people by dotting their foreheads with a mix of ash and ox blood. In 2004, government funding helped scale the forehead dot into a citywide mud fight in hopes of attracting tourists. So here I was.

A girl takes a selfie at the citywide mudfight known as the Monihei Festival

But domestic tourism in China is less about getting off the beaten path than “beating a path to state-sanctioned points of predefined interest,” anthropologist Chris Vasantkumar writes in the book Mapping Shangrila. So in the early 2000s, as it was developing its mud fight plans, the Cangyuan county government identified additional attractions nearby that would bring tourists to this remote corner of China. So came about the rediscovery of Wengding, “China’s last primitive tribal village.”

Wengding is a photographer’s dreamscape. Stilted wood houses with grass roofs are clustered together in a valley surrounded by banyan trees hundreds of years old. Wrinkly Wa women in colorful headscarves and traditional dress sit on their porches smoking long tobacco pipes. They smile warmly, revealing teeth blackened with tree resin to prevent decay. One tourist website touts: “[Wengding] remains a living village where life goes on as it has for ages.” But tourism development, the modern economy and government intervention have despoiled this primitive tribal village. It’s no longer primitive, the tribe is divided and the village is but a shell of the once-vibrant Wa community—all in the name of cultural preservation. It turns out you can’t save culture by selling it.

Tourism de force

Thousands of ox skulls line the final kilometer to Wengding. “It’s so over the top,” Yang Jianguo tells me. “The government does whatever it thinks tourists want.” Jianguo is 52 years old and the seventh generation in a succession of Wa chiefs. Small-framed and soft-spoken, he’s also a man of opinion. At Wengding’s entrance, a tourism development company has constructed a 25-foot tall sculpture of a “native,” naked and grinning, and a hundred more ox skulls cover a concrete tree nearby. “These are not Wa culture,” he says. “Sculpt an ox. Plant a tree. Real trees have spirits! That is Wa culture!”

Technically, Jianguo’s father is still chief. At the age of 16, he had entered public security school in Kunming, the provincial capital, but was purged as a landlord under Chairman Mao Zedong and sent back to Wengding. Now 83 and almost deaf, Chief Yang mostly stays upstairs in the family’s stilted home and smokes Cloud Tobacco cigarettes. His wife, a living portrait, sits next to him in her ethnic dress and puffs on her pipe.

Jianguo takes me on a tour of the village. He points out where the tourism development company installed power lines, and where they dug them up again to install water piping. He notes the stone-paved pathways dug up each time, and the piles of stones and gravel in Wengding’s main plaza, unmoved for six months. “We have no idea what they’re thinking,” he says. “They love to do things twice and seem to be just looking for ways to spend more money.” Jianguo points out the new walls as an example, wondering what was wrong with the old ones. “Make everything new—is that cultural preservation?” he asks rhetorically. “Is that what tourists want to see?”

There is something about Wengding tourists want to see. Some 80,000 visitors came last year and local officials expect the number to increase, especially since the completion of the new highway to the village last year. Entrance tickets have provided additional funding for improvements and many locals sell tea, wild honey and ethnic handicrafts for extra income. But peak season is short-lived. Tourists come by the busful for three days during May holiday—usually day-tripping from the “rub you black” festival—and several more days during the October holiday. The rest of the year, tourism is slow, with just a handful of tourists visiting each day, few of whom actually stay or eat in the village.

A moba, or Wa spiritual leader, plays a gourd flute for tourists during May holiday

But more challenging than erratic income streams, according to Wu Xiaolin at Yunnan University of Nationalities, is that ethnic tourism turns real life into performance. Dr. Wu first visited Wengding in 2006 for Ph.D. research and has followed the village’s development since. “A tension arises between the economic and the sacred.” She recounted villagers wrestling with that tension around their “sacred forest” ceremony. The secretive rite honors the forest god and cleanses the village for the coming year, but only one male elder from each household is allowed to attend. One year, an enterprising young leader invited tourists to join for a 100 yuan fee. “The younger generation is more economically minded and open to change,” she told me. “But the elders worry and fear change.”

Jianguo sides with the latter. We sit on his front porch sipping tea from his spring crop as a tourist’s drone buzzes overhead. A Wa-language sign reading “ny iex jao yaong” hangs above his doorway to attract passersby: village chief’s house. Two middle-aged Chinese tourists walk by in silence and enter Jianguo’s home, cameras in hand. As they leave, again without saying a word, a young couple from Sichuan see the sign and stop. “Is the chief here?” they ask Jianguo. He directs them up the stairs and inside where they stand awkwardly observing his parents from across the room. The girl’s face glows in the dimly lit room as she taps her phone and giggles nervously. The chief and his wife, accustomed to visitors, sit up straight and look toward the camera. The boy stands off to the side, uninterested, but dutifully holding his girlfriend’s coat and purse as she takes a sweeping video of the room to post on social media. The ten-second clip suffices and as quickly as they came, they’ve gone.

The last of the day’s tourists meander to the parking lot as the red sun dips toward the banyan trees in the west. But they aren’t the only ones to go. Last summer, Jianguo’s neighbor and her family moved to a new village a kilometer away that the government built to relocate Wengding residents. She packs up her tea and woven satchels and walks home. As the light fades, I stroll through the last primitive tribal village. But for a handful of televisions that glow through doorways, the settlement is dark. Houses are boarded up, some for the night, some for the long term. Even the village square, traditionally the heart of the community, is empty, save for a blue-faced man on his phone. Wengding is no longer primitive, it’s abandoned.

The China Eastern Airlines Demonstration Village where residents relocate from Wengding village

Rural suburbia

The next morning, there is no rural bustle—no smoke billowing from homes and no chickens squawking. There are no people. Only about 20 families still live in the old village and the rest haven’t shown up for work yet. I make my way over to the new village.

A wooden sign points the way: “Wengding Village—The Poverty-alleviation Project of China Eastern Airlines.” A stone-paved road winds around rice paddies and three-foot-high characters that read: “When you drink water, don’t forget who dug the well for you; when you prosper, don’t forget the Communist Party.”

If villages could have suburbs, this was it. Rows of identical wood-paneled houses line the streets, each with a Chinese flag flying from its roof. The twelve core Socialist values hang from solar-powered street lamps on the main thoroughfare: patriotism, harmony, democracy, freedom, rule of law—a promenade of aspirational goals.

“It’s a little better here,” Xiao Anshi tells me at China Eastern Airlines Demonstration Village Unit #019. Her address hangs on the porch behind her next to a portrait of Chairman Xi. “We can strive for hygienic, civilized lives.” Mrs. Xiao is friendly as she takes a break from chopping pig feed, slivers of banana stalk covering her arms from the elbow down. I ask if she wanted to move here. “The government made us move,” she replies matter-of-factly. “The people staying in the old village aren’t obedient.”

Relocation villages like this one have sprung up all over China’s countryside as the state tries to better integrate rural residents into society and the modern economy. Typically, the government will fund construction of small housing complexes near main roads to sell units at a discount or even give to impoverished residents from surrounding areas. In Wengding, however, the focus is on relocating residents of the old village. “Their homes are so dark and dirty,” Li Zhuqing, the Party official, told me during our lunch about Wengding’s preservation. “We can’t let them live like that.”

Last summer, the government finished construction on the new village and began encouraging villagers to move. By fall, only about 20 families had moved into the China Eastern Airlines Demonstration Village, most preferring to stay in their ancestral homes, some of which have been in the family for seven generations. But local officials have allegedly pressured village elders to move and bring their relatives with them. One influential retired elder is reportedly back on the government payroll now that he relocated. “The government has ways of persuading people,” a hold-out in the old village told me, asking to remain anonymous for fear of trouble. “If you don’t comply, your life suddenly gets very difficult.” Applications to various government departments can get caught up in red tape. Entitlements under China’s preferential policies for minorities might not be disbursed. Clan by clan, the old village emptied out.

“It has divided the village,” the holdout tells me. Residents feel betrayed by those who’ve left and people in the new village think those holding out are stubborn and selfish. Competition for business and economic disparity within the village further stokes the division. “Our great unity is gone,” she sighs. “People used to share with one another. Now they don’t.”

In the new village, one neighbor also dislikes the disunity. “People should obey the government,” he says. “It has the people in mind.” The man, also surnamed Xiao and also with a portrait of Chairman Xi hanging on his porch, invites me to sit with him as he fixes a broken-down motorized cart. “People start to break down, too, when they get old,” he reflects with grandfatherly wisdom. Xiao is 65 and had double bypass surgery several years ago. But his household is officially poor and receives substantial health benefits from the state. For his $8,000 surgery, he paid only $800. The family sees the upsides. “It’s hard to let go of the old village,” Xiao tells me, “but there’s no other way.”

Zhao Sanmu also benefits from health subsidies. “I wouldn’t be alive if the government didn’t cover my dialysis,” he tells me. Zhao’s kidneys failed three years ago and he undergoes hemodialysis three times every week. He shows me the bulging veins on his forearm where nurses inject the needle. A fresh Band-Aid covers the wound from his last treatment. “Each time costs about [$200],” Zhao says. “We could never afford that.” So he is grateful, which is perhaps why an identical portrait of Chairman Xi hangs on his porch. But he complains about local leadership. “Officials just want to complete their tasks, they don’t care how it’s affecting our lives. Leaders should come into our homes to actually talk with us; instead, they walk around the beautiful new village and see what they want to see.”

Communication, it seems, is not the local administration’s strong suit. “The government never listens to villagers’ input,” the anonymous holdout tells me. “Plans are already finalized.” From her house, we look down on the first relocation village the government started building for Wengding residents. Ten units were already completely built when the government realized they would refuse to move. “In Wa culture, you can move up but never down,” she explains. So the government began a second village higher up.

But some lessons are never learned: The second village was also built without local input so the “modern” housing design is unable to accommodate a central fire or the sleeping arrangements prescribed by Wa customs. It strikes me that Wa customs themselves seem to be the greatest barrier to their preservation.

One such custom was highlighted in a 2019 investigative report by Cover Story (封面).

The Wa differentiate between an auspicious death—from natural causes—and inauspicious—from sickness, an accident or childbirth—and custom holds that in the event of an inauspicious death the family should tear down its house and rebuild it.

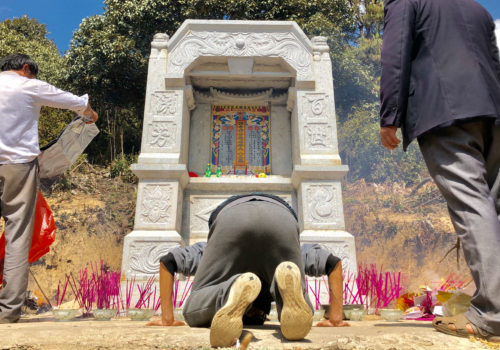

A Wengding man died inauspiciously several years ago. At the time of death, the Xiao family couldn’t afford to rebuild, but early this year, thanks partly to income from tourism, they decided to finally do so. The house was also on the verge of collapse. They consulted a moba—a Wa spiritual leader—to calculate the auspicious day for deconstruction and applied to the government for permission. But customs get complicated when your home is a state-owned cultural relic; residents have business operating rights but do not hold property rights. The Xiaos received no official response from the local government so when the auspicious day finally arrived, the family hosted a customary feast for the community. Able-bodied men and black-toothed women all showed up, as did “the higher ups.”

You can’t tear down the house, they were told.

But the Xiaos were past the point of no return. “It’s our house. If we want to tear it down, we’ll tear it down. We should have the right,” Xiao Yidao said in the Cover Story interview. “The government says ‘cultural relic.’ I don’t even know what that means.”

Self-interest and state-interest do not always align and, when you live on government-owned land in a government-confiscated house on a government-supplied pension, the space between diverging interests can be difficult to navigate. Or, in some cases, it’s straightforward. The next morning, the Xiaos tore down the house.

“If we didn’t protect Wengding, the entire village would have been ruined years ago,” Li Zhuqing tells me from her experience at the Bureau of Culture and Tourism. I don’t doubt what she says is true based on what I’ve seen in other “modernizing” villages across Yunnan. But she also suggests that officials did communicate earlier, and that the Xiaos refused to listen and have ulterior motives. Perhaps. Maybe minorities in China sometimes play the culture card to their policy advantage. And maybe the local government sometimes acts against the interests of its constituents. Maybe both sides contribute to the challenges. Indeed, maybe the system’s very opacity intentionally lends itself to negotiation on the margins.

“There’s also a lot of thought work involved,” Li continues. “Our leaders want them to be able to live like us normal people. They don’t understand the direction our society is going; they can’t just continue to ‘depend upon the heavens for food’” (靠天吃饭).

Growing pains

My last night in Wengding, I sit by the fire with Jianguo and his parents upstairs in their home. His daughter and her boyfriend call from southern China where they work in factories. Their faces fill up Jianguo’s phone screen.

“You should call more,” Jianguo tells the young man.

The boyfriend laughs nervously. “Yes, I will call every week,” he says dutifully.

“Just two or three times a month is enough,” Jianguo replies, followed by more nervous laughter and a long silence.

The young man continues tentatively: “Maybe my parents should visit at the end of the year, just before New Year.” Jianguo coughs. Both men shift uncomfortably. This is the cultural equivalent of asking permission to marry his daughter.

“That’d be fine,” Jianguo finally says to the young man’s relief.

The conversation is brief. Soon, Jianguo’s mother has the phone and chats with the bride-to-be. Chief Yang smooths out blankets on the bamboo floorboards and lies down on his side to watch the television across the room.

The fire burns down to a warm glow in the middle of the room and our conversation turns again to Wengding. “Some want to move back already,” Jianguo says, referring to new village residents. They see the old village holdouts haven’t actually lost their benefits and now feel the government tricked them.

Still, in Wa culture, homes rather than gravesites are central to honoring ancestral spirits, so moving back would be complex if not impossible for most. “They all fell for it,” Jianguo says sadly. “Maybe it will take five years, but eventually they will realize what the government has done is wrong.”

Jianguo’s words hang heavy in the dark room. Is he prescient or just pessimistic? Are others genuinely more optimistic or just more obedient? Only time will tell if ethnic tourism—the government’s proverbial rice seed—will sprout and allow the Wa people to continue to flourish.