BERLIN — On a gloomy, gray morning in early February, I sat on a hard plastic chair at the Bürgeramt Tempelhof, a municipal office in southern Berlin, staring up at a large screen on the wall. A half-dozen or so Germans of varying ages sat in the socially distanced chairs around me: Some were there to change the address at which they were registered; others were renewing their passports or getting parking permits. All of them were equally transfixed by the screen, awaiting a two-tone ding! and the appearance of their 6-digit appointment numbers, boredom with a hint of despair on their faces as they fiddled with paperwork in their laps or checked their phones.

I had come because, nearly four years after arriving in Germany, I decided it was finally time to get a German driver’s license. My appointment, booked weeks in advance at an office across town from where I live, was scheduled for precisely 11:12 a.m. Around 11:25, I finally heard the telltale ding! and saw my number show up on the screen.

The appointment itself was relatively painless, at least by Berlin standards. A middle-aged man at a nondescript desk filed my application with minimal disdain and, after debating with a colleague, told me that, since my license was from the District of Columbia and not a handful of other US states, I would need to take the written driving test. I paid the fee and was informed I would get a letter with details about the test in about a month. I left feeling, as I always do in Berlin municipal offices, far more exhausted than I’d been on entering.

When most people of the world think of Germany, they picture order; they think of efficiency, of German engineering. Those concepts may actually apply at, say, BMW factories in Bavaria, but at least in Berlin, German efficiency more often feels like the punch line to a joke.

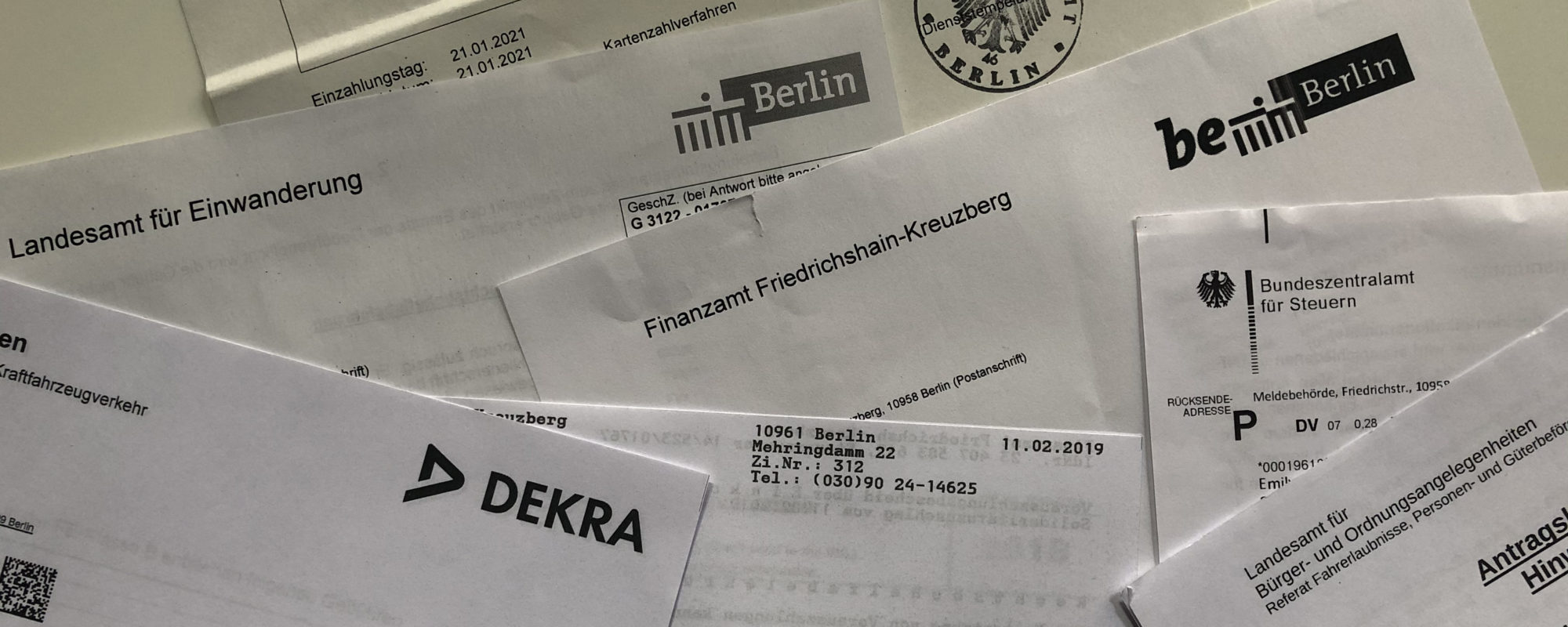

That’s because dealing with Berlin bureaucracy often borders on the absurd. You can bring a literal ream of paperwork with you and be asked for the one tiny thing you didn’t think of, or something that wasn’t on the list of requirements in the first place. A rule that’s ironclad for you—absolutely no speaking English at the Foreigners’ Office, for example—could be relaxed on a whim for someone else. The sometimes Kafkaesque experience is made all the more intimidating by the Amtssprache, or bureaucratic language, which can be a bit too much even for native German speakers: As a non-native, managing to discuss my Aufenthaltserlaubnis (residence permit) or Einkommensteuervorauszahlungen (quarterly income tax prepayments) feels like a major victory in itself.

In the weeks after my Bürgeramt appointment, I downloaded a mobile app to take practice driving tests. Unlike the one I remember taking as a teenager at a California DMV, the German exam is known to be notoriously tricky—especially the English-language version, which is at times poorly translated. As I drilled myself on the more than 1,000 practice questions, I came across things like impromptu street racing (you’re not supposed to do it) and so-called “disco accidents” among young drivers (apparently, when young people get hyped up and make driving mistakes late at night after partying). Countless expat forums and listservs endlessly trade tips about the process, which is ultimately not that difficult but takes time and diligence and, above all, willingness to memorize rules and questions that often have nothing to do with real-life situations.

Normally, the quirks of German bureaucracy are simply a fact of life—something we simply bear with a strained smile and a grudging Danke schön, filing the bad experiences away to commiserate with friends afterward. But these days, the downsides of the antiquated, rigid-until-it’s-not system are having a very real impact on Germany’s ability to handle the coronavirus.

More than a year into the pandemic, Germany has gone from being touted as a global model to seriously struggling in the face of its deadly third wave. Fueled by the B.1.1.7 variant, cases are rising rapidly and ICUs are starting to fill up. And where the United States is racing ahead with its vaccination program, getting shots in arms as fast as possible, Germany’s vaccinations can be described as sluggish at best.

German bureaucracy, when paired with actual life-or-death situations, is repeatedly falling short. Here, again, the absurdities are unavoidable: To get a vaccine appointment, you must first receive an invitation letter by postal mail; in that letter is a code you use to make an online appointment at one of the city’s half-dozen vaccination centers. Without that code, even if you know you’re part of an eligible group, you can’t schedule an appointment.

Some elderly Germans eligible for the vaccine since earlier this year couldn’t be contacted by mail to schedule their vaccinations because of strict data protection rules. And stories have come out about highly vulnerable people who are eligible for the vaccine and make an appointment—a recent cancer patient, for example—but are turned away on arrival for registering in the wrong system.

More than a year into the pandemic, Germany has gone from being touted as a global model to seriously struggling in the face of its deadly third wave.

Like their counterparts around the world, Germans are weary these days. The slow vaccine rollout and proposed new restrictions are contributing to a loss of faith in the government’s ability to handle the crisis. But where other countries seem to be adapting their strategies based on the situation as it unfolds, Germany remains rigid, watching a wave of new cases crash over it, seemingly unable to respond with anything but the same kinds of measures it’s used all along.

“We want to complement the proverbial German thoroughness with German flexibility,” Merkel said at a recent news conference, adding that the strategy for vaccinations should be “as fast as possible, as flexible as possible.” Germany? Flexible? Perhaps aided by my experiences with German “flexibility” over the years, my reaction was the same as those of many observers: I’ll believe it when I see it. (And in the meantime, I’ll get vaccinated back home in the States.)

* * *

On a crisp, sunny morning a few weeks after my Bürgeramt, I hopped on the U-Bahn subway and made my way back across town to the driving association where I would take my test. I was ready: I had studied all 1,139 practice questions (including the one about “disco accidents”), had called the test center and assured that yes, I had sent my fee by bank transfer the requisite five days in advance, and carried a clear plastic folder with all the necessary paperwork. After answering all 30 test questions and seeing a message pop up on the screen telling me I’d passed, a mere 15 or so minutes after arriving at the test center, I thought to myself: Finally, a simple interaction with German bureaucracy!

I should have known better. The man at the front desk congratulated me on passing the test, but couldn’t print my temporary license: It required a special kind of paper he didn’t have, he said with an apologetic smile. He sent me out of the building and around the other side, to another desk, where a blond woman told me that she, too, lacked this particular kind of paper.

She directed me to another hard plastic chair in a waiting room off to the side. From my seat, I heard her going from office to office asking her colleagues for help. After what must have been half a dozen conversations, she returned half an hour later with the prized printout and sent me, finally, on my way. “German bureaucracy,” she said, shrugging her shoulders.