SHAFARON, Nigeria — In late 2017, ethnic Fulbe herders became embroiled in a series of deadly tit-for-tat attacks with Bwatiye[i] farmers outside the town of Numan in eastern Nigeria. By the time the crisis ended in January 2018, around 150 people were dead,[ii] a dozen villages burned to the ground and hundreds of Fulbe who had called Numan home had fled.

When I arrived last March, I wanted to construct a detailed narrative of one case of farmer-herder conflict that could shed light on the larger phenomenon in West Africa. Considering that the killing ended in January 2018, I assumed I would be talking to people about events in the fairly distant past. As I expected, I was told about the land disputes that sparked the violence, about the government impunity that allowed it to occur and the conspiracy theories that have festered since. However, I was not prepared for how unresolved those issues remain and the palpable tension that still exists between the two communities.

Over the last decade, localized skirmishes between herders and farmers over scarce land and water resources have claimed the lives of around 10,000 Nigerians, making it the second-most deadly security crisis in the country after the Boko Haram insurgency. Clashes are often prompted by hyper-local disputes that spiral into deadly retaliatory attacks, sometimes leaving hundreds dead.

While those conflicts are localized—meaning that neither side has organized a national or regional movement—they all stem from, and are exacerbated by, land disputes, weapons proliferation, government impunity and conspiracy theories.

* * *

The town of Numan, population 80,000 and the capital of the eponymous local government area, stands on the south bank of the mighty Benue River. The town’s southern flank opens onto rolling hills of grass dotted with clusters of trees, meandering seasonal streams and the odd murky pond. When I was there in March, toward the end of the seven-month dry season, the trees had lost their leaves, the Benue had receded to half its size, most ponds had evaporated and the hills were covered in desiccated grass. Then, as it usually does in May, it began raining and, like much of savannah West Africa, the landscape was transformed overnight. Lush fields of grass sprang up and the river flooded its banks, rejuvenating ponds and nearby forests and catalyzing an explosion of life.

Bwatiye, who today are predominantly Christian, first settled in the Numan area in the 19th century, fleeing the persecution of the Sokoto theocracy.

Different clans of Fulbe, on the other hand, have for centuries survived the dry season by establishing seasonal camps in the river valley, which includes Numan. While some clans migrated to northern Nigeria when the rains started, others just migrated within the greater Numan area, and therefore have longstanding relations with their Bwatiye neighbors.

“I grew up living with Fulani [another word for Fulbe] people in the same way as my grandfathers,” Tashini Titus Dauda, the short, 60-year-old chief of the Bwatiye village of Shafaron, explained. He described how during the rainy season, Bwatiye farmers grew large fields of grain, while Fulbe herders decamped to Chabbal, an elevated area around 10 miles away. As the rains tapered off in October, herders gradually brought their livestock closer to the river, paying farmers to graze in recently harvested fields. Once the river receded, they would move from Chabbal to a settlement they called Shelewol, a collection of huts nestled between Bwatiye villages, the Benue River, and a pond that lingered through the dry season.

“They brought their milk; we gave them grains,” Dauda remembered. “We had a very good relationship.”

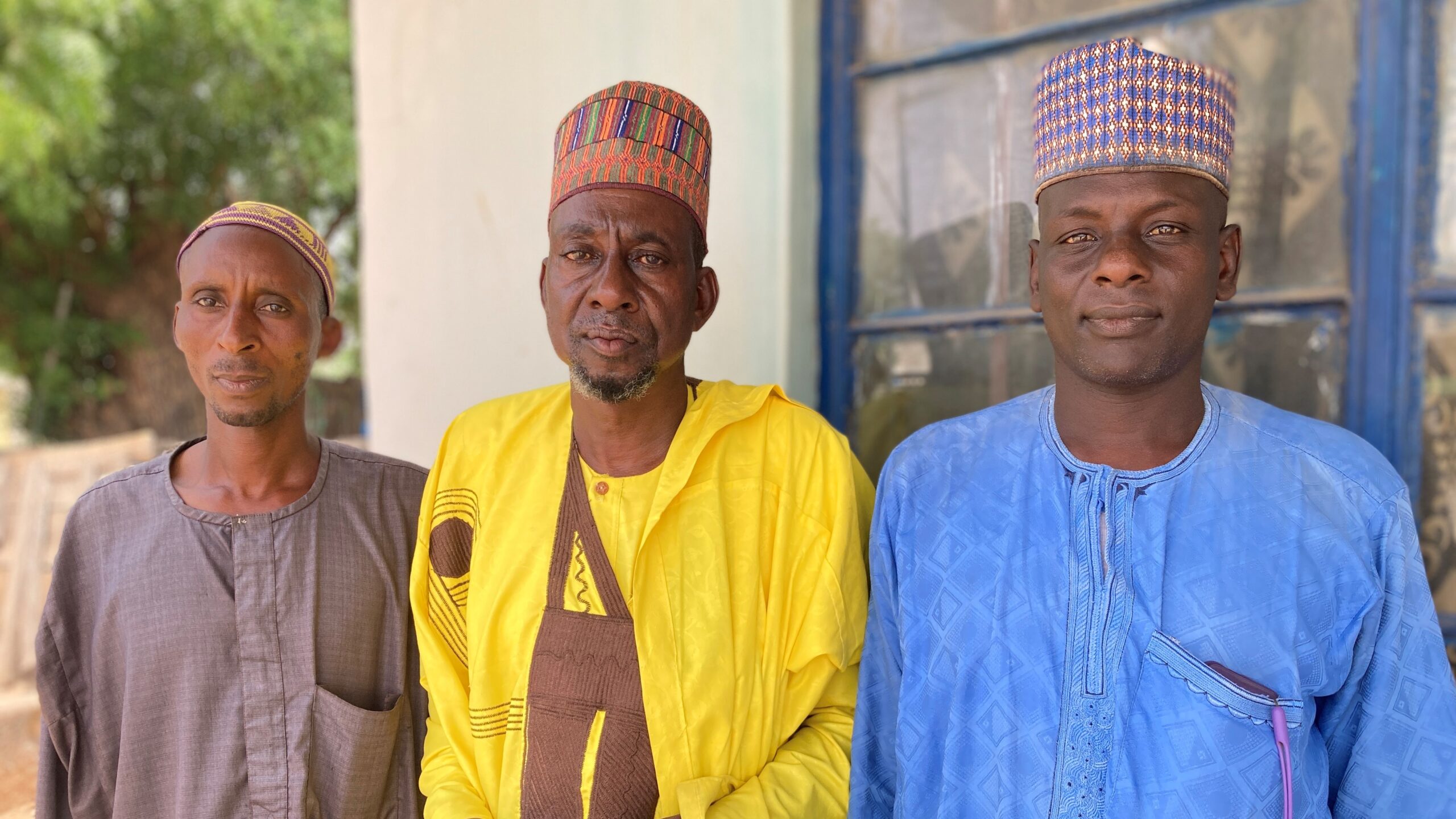

Ardo Kaku Galadima, the now-exiled chief of the Shelewol Fulbe, confirmed Dauda’s general narrative.

“They did not farm our livestock corridors and pastures, and we avoided their fields until after they had harvested,” the elegant chief-in-exile said. Disputes over crop damage were rare, both sides say, and when they did occur, they were quickly and fairly adjudicated.

However, over the last few decades, that fine-tuned system began to break down. As successive droughts struck northern Nigeria in the 1970s and 1980s, Fulbe herders from the north began spending more time in comparatively lush Numan. These newcomers did not share the same history of mutually beneficial relations with Bwatiye communities.

“We do not know them or their leaders,” said Pleangoto Kaanti, the headmaster of Shafaron’s primary school. “When we have a problem with them, we do not even know whom to go to.”

Concurrently, improvements in farming technology enabled Bwatiye farmers to cultivate more land for longer periods. With motorized pumps, they drew water from the river and larger ponds to grow another crop during the dry season. Fulbe herders began complaining that their grazing routes were now vegetable gardens and rice fields.

“Everywhere you look there is farming,” Galadima said.

Around the same time, herders across Nigeria began carrying light automatic weapons, mostly to protect themselves from cattle rustlers. Disputes over crop damage or the killing of livestock between the unfamiliar parties turned deadly.

Security and judicial services often failed to arrest or prosecute perpetrators. One side would take revenge, leading to a cycle of retaliatory attacks.

In January 2016, clashes of that nature between Bwatiye farmers and Fulbe herders 30 miles east of Numan left 19 farmers and one police officer dead. Six months later, similar attacks occurred even closer to town. Despite the mounting tensions in the area, Fulbe and Bwatiye around Numan continued their seasonal activities, and in late October 2017, Galadima and the other Fulbe families made their annual move from Chabbal to Shelewol without incident.

* * *

Early in my conversations with Fulbe and Bwatiye leaders, it became clear both sides told very different stories about what exactly had sparked the weeks of retaliatory killings in late 2017. However, the stories of both sides ultimately revolved around disputes over how to share land and water.

Fulbe leaders insist the crisis started on November 17 when Honest Irmiyya, the then-Hama Bachama (a title given to one of the Bwatiye kings), ordered all Fulbe to leave Numan. They claim that three days after the expulsion order, Bwatiye farmers chased Fulbe herders off their pasture, killing two in the process.

Bwatiye communities, on the other hand, claim the violence began when Fulbe herders invaded an okra field on the morning of November 20, and when confronted, responded by shooting a farmer.

Regardless of what sparked the violence, it is generally accepted that around mid-day on November 20, a Bwatiye mob from Shafaron (and in Fulbe’s telling, surrounding villages)[iii] descended on the Fulbe encampment of Shelewol. The Fulbe men were out of the village, leaving the children, women and elderly alone. When these people saw the angry Bwatiye mob approaching from the east, they tried to escape by running south toward Chabbal.

According to Galadima and confirmed by a Bwatiye elder from the nearby village of Kikan, this group, mostly women and small children, was intercepted by a second mob approaching from Kikan that encircled them and hacked them to death with machetes. Shelewol was looted and set ablaze.

That evening, while the Fulbe gathered their dead, including many children, the commissioner of police in Adamawa State assured the public the authorities would arrest the perpetrators. Police and military vehicles patrolled Numan town and the main roads.

Galadima and other Fulbe leaders, however, claim no one even interviewed them. Although everyone knew who the perpetrators were, no one was arrested.

A war of words erupted as news of the attack spread. The chairman of the Muslim Council for Adamawa State called the attacks “ethnic cleansing” and the sultan of Sokoto warned against misconstruing “patience for weakness.” Pene Da Bwatiye, a Bwatiye communal association, responded that those were “weighty words/phrases mischievously used to incite well-meaning Nigerians and tarnish the good name of our peace-loving people.”

Instead, they accused Fulbe herders of “terrorizing farmers, eating crops and destroying livelihoods all over Nigeria.” As tensions rose unchecked and perpetrators roamed free, the government’s promises to hold those accountable felt increasingly hollow.

Despairing of ever getting justice, a small group of Fulbe took matters into its own hands. In the days after the attack, relatives of the victims approached their distant kin at weekly livestock markets offering kola nuts—a traditional way to ask for assistance—and requested support to avenge their dead.

Toward the end of November, word spread that dozens of heavily armed herders were gathering in the forests around Chabbal. When the police went to investigate, a firefight ensued, leaving six officers dead.[iv] The failed raid fueled rumors of an impending reprisal and a beefed-up security presence. Bwatiye women, children and elderly fled their rural villages. While Numan’s bus station heaved with people trying to get out, an eerie quiet fell over the rest of the town.

As the sun rose on December 4, around 100 Fulbe herders attacked the Bwatiye villages of Lawaru and Dong. In the neighboring Bwatiye communities of Pullum, Shafaron and Kodomti, people saw the smoke on the horizon and ran to the banks of the Benue. Kaanti, the headmaster in Shafaron, was among the few who grabbed a machete and started running toward the fighting.

“Then I met people on the road who said the Fulani were coming to Shafaron next,” Kaanti said. “I turned around and ran back to my village. The Fulani had guns; we had cutlasses. We could not fight them.”

He joined the dozens who fled across the river in fishing canoes, looking back as their village was engulfed in flames.

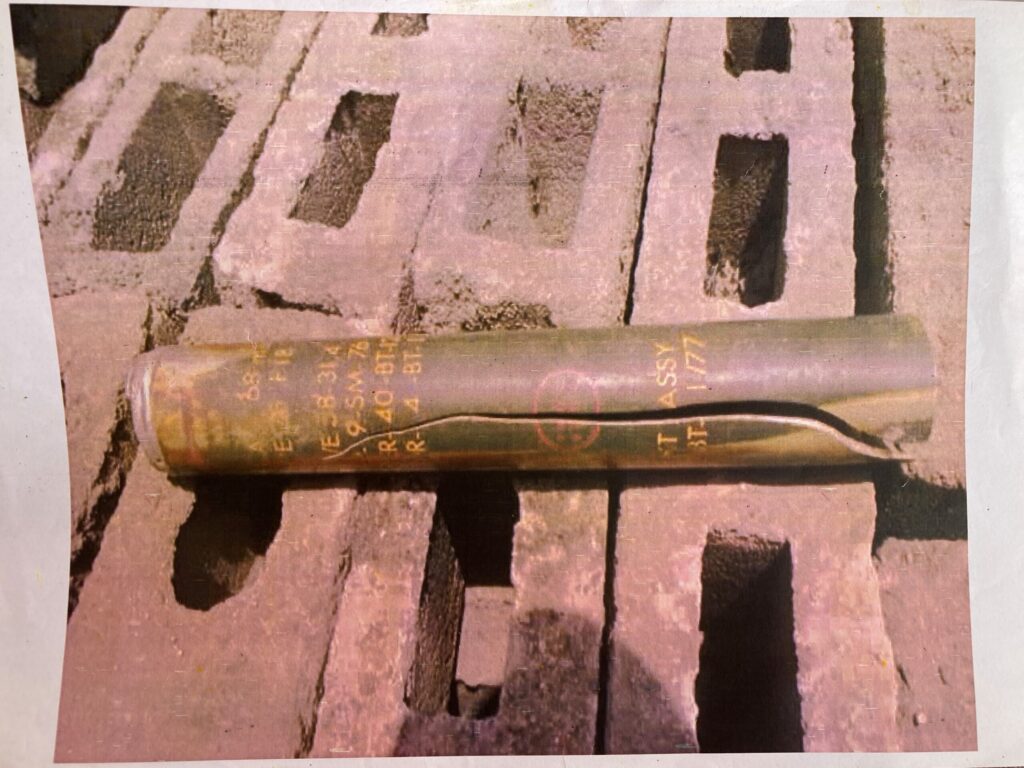

Meanwhile, at an air base in the regional capital, Yola, the Nigerian air force scrambled a jet and an attack helicopter. From hundreds of feet in the air, they fired rounds and dropped bombs onto the confusing scene below. The air force later said these were “warning shots” to deter the attackers, but most of the bombs fell in and around the Bwatiye villages being attacked.

Amnesty International later tabulated that 50 people died as a result of the herders’ attack, while 35 people died in the air force’s barrage. For many Bwatiye, who were already suspicious of the government, the military actions were further evidence of government complicity.

The cycles of violence were not over. While government officials again promised those responsible would face justice, small groups of Bwatiye attacked Fulbe hamlets between Shelewol and Chabbal. No one was killed, but houses and property were burned to the ground, and the few Fulbe left fled to neighboring Local Government Area Mayo Belwa. The last major attack occurred in late January, when a small group of Fulbe herders launched a nighttime raid on the village of Kikan, which had been spared in the December 4 attack,[v] killing three people and looting livestock and other valuables.

By the end of January 2018, between 130 and 180 people had been killed. No Fulbe remained in the rural areas around Numan town. Crops were uprooted, livestock slaughtered and millions of naira (thousands of dollars) of property destroyed. None of the responsible parties had been arrested or prosecuted. And rumors of grand plots and government complicity were already spoiling any chances of reconciliation.

* * *

As the tuk-tuk I hired trundled between the Bwaitye villages that had been attacked on December 4, my eye was drawn to a band of florescent green that stood out amid the plains of dry grass. As we got closer, I started taking pictures of a newly sprouted rice paddy with a pond in the background. Before I came to Numan, I thought my dispatch would end with the end of the crisis. However, the more I spoke with people, the more I saw that the structural drivers of the conflict remained unchanged, and the prospect of future violence remains all too real.

Using satellite imagery I later saw how within a year of the Fulbe fleeing, Bwatiye farmers began cutting down trees, delineating parcels and installing motor pumps around the large year-round pond near where Shelewol used to sit.

When I brought these rice paddies and gardens up with Galadima, he acknowledged that they contribute to Bwatiye food security. However, he insisted, the cultivation also happens to be taking place on land that was prized by generations of Fulbe as dry-season pasture for their livestock close to both the pond and the Benue River.

While Bwatiye farmers expanded their fields, back in Yola, the government established a “technical committee” to investigate the causes of the violence and propose workable solutions. Two years later, they unveiled a balanced account of the crisis that recommended protecting grazing routes for herders, disarming communities and paying compensation to victims. To date, the government has failed to implement those initiatives. No one has been prosecuted, and victims have yet to receive compensation.

The only efforts to reconcile Fulbe and Bwatiye in Numan have taken the form of mediation committees established by nongovernmental organizations. In 2020, a coalition of international conflict-resolution organizations established a network of “community observers” among Bwatiye and Fulbe to serve as an early warning team. If the community can’t handle a dispute themselves, they can refer the case to dialogue committees that can engage more powerful authorities.

Calvin Yusuf, the chairman of Community Security Architecture Dialogue in Numan, is convinced that if the project had been in place in November 2017, the deadly escalation could have been averted. However, he said, the program has its limitations.

While the dialogues they coordinate are useful, participants tell him they need more than words to restore livelihoods and ensure justice. That should be the work of the government, he said, but “the level of trust in government is reduced, so people look to NGOs instead.”

In the vacuum created by government inaction, dangerous conspiracy theories have festered. During my first meeting with the Hama Bachama, he explained that what had happened in Numan was no mere “farmer-herder conflict.” Instead, he portrayed the 2017 crisis as part of a conspiracy in which the supposedly Fulbe-dominated federal government was perpetrating ethnic cleansing against Christian minorities. He pointed to the actions of the Nigerian air force on December 4 as evidence that the government at the time was working with herders against their community.[vi]

A Bwatiye-produced report on the crisis spells out the narrative clearly:

The pogrom to annihilate and subjugate the Bwatiye Nation is being executed systematically with the Fulani terrorists under the garb of Herdsmen who have been invading Bwatiye settlements across the length and breadth of Adamawa State with the tacit support and backing of some powerful groups both inside and outside Adamawa State with the collusion of both Adamawa State Government and the Federal Government.

This conspiracy theory has undermined trust in the government even further and poisoned relations between the two communities. When the state government tried to set land aside for herders as a part of a plan to formalize the livestock sector, Bwatiye protested, fearing the ranches would be used as training grounds and arms depots for Fulbe militants.

The current Hama Bachama insisted to me he would never approve such a project, which he cast as a thinly veiled attempt by Fulbe to seize Bwatiye land.

* * *

For almost five years, Fulbe herders avoided bringing their livestock to Numan on the orders of the Hama Bachama.

“Truly,” Yusuf, the chairman of the Community Security Architecture Dialogue told me, “this is a big reason why there were no disputes during that time.”

Then in late 2022, under pressure from the state governor, the Hama Bachama reluctantly ordered his sub-chiefs to allow Fulbe herders to return.

In almost every Bwatiye village I visited, the Fulbe’s return was resented or viewed as extremely suspicious. Many Bwatiye expressed concerns that the Fulbe herders that returned to the area have been almost exclusively young men.

“Why don’t they bring their families?” asked Likita David, an elder in Kikan. “Are they planning something?”

The issue of compensation also looms large.

“Dozens of our people are dead, and there is still no compensation or justice,” said Jared Hanya, the chief of Dong, one of the first villages attacked on December 4. “How can we have good relations with them?”

During my audience with the Hama Bachama, he stressed multiple times that there could be no peace until his people receive compensation for the December 4 attack.

Meanwhile, Galadima and other Fulbe were pleased to finally be able to bring their livestock back to Numan.

“The Bwatiye keep saying it is their land and they are the only indigenes,” he asserted, his voice becoming deeper. “But we were also born here. Our fathers were born here and our children were born here. We are also indigenes!”

However, when his sons led their cattle into the Numan area, they were surprised to find their traditional paths blocked, he said. The shrubs around the year-round pond where they previously survived the deepest pits of the dry season were now a lattice of rice paddies, leaving them with fewer areas to access the pond water.

“This is not how we shared the land in the past,” Galadima said. “It is bringing more disagreements and arguments than before.”

Furthermore, Fulbe claim, dozens of cattle have been slaughtered in isolated incidents since they returned to the area.

“We tell the police and they do nothing,” he complained. “We still do not feel safe, and that is why we do not bring our wives and children.”

As I left Numan, I felt sick in the pit of my stomach. Fulbe herders seemed distrustful of the government and their own elites, and thus were more inclined to seek revenge on their own. Meanwhile, Bwatiye farmers quickly recast altercations over crop damage as part of a genocidal plot, making local efforts at restitution and reconciliation far more difficult.

While Fulbe and Bwatiye assume the worst of one another, I could not help but notice they all articulated the same frustrations about the government.

“Both sides want the same thing: justice and accountability,” Yusuf said. “However, as long as they refuse to engage with one another, they will be unable to address the deeper issues of land governance and justice that plague both communities.”

Endnotes

[i] The term Bwatiye refers to the language and the broader ethnic group, which today are divided into the Bachama and Batta kingdoms.

[ii] The number of people killed on both sides is very hard to confirm. The general range is from 130 to 180.

[iii] In the interviews I conducted, people from Shafaron claimed that Bwatiye youth from nearby villages joined those from Shafaron in the attack on Shelewol. Almost all Shafaron’s neighbors denied that they participated.

[iv] This was first reported in the press on December 1, and it is unclear whether it is the same event to which Ardo Kaku referred.

[v] Bwatiye claim that on December 4, young people from Numan rushed to Kikan to defend the village. Fulbe sources indicated that the air force’s assault did halt the attackers, forcing them to turn around before they struck every village they believed had been involved in the massacre at Shelewol.

[vi] A recent report by Reuters detailed how the Nigerian air force has a history of “accidentally” bombing civilians, including a refugee camp where people were killed and, more recently, a group of Fulbe herders.

Top photo: The mass grave outside the village of Dong