ALEXANDROUPOLI, Greece — On the feast day of Agia Varvara, the protector of children, my friends Georgios and Vasiliki invited me to Vasiliki’s family home to try her grandmother’s version of varvára, a sweet Thracian porridge of boiled wheat, raisins, almonds, chopped walnuts and cinnamon. As we enjoyed the nutritious snack, our conversation turned to the American soldiers who, over the past week, had become omnipresent in the city. Georgios had arranged for a group of them to explore the hiking paths he’d developed with our friend Mr. Michalis, a veteran hunter with a playful streak. Mr. Michalis took them to a waterfall, showed them ancient walls and a wine press and reported that they were “good kids,” nice and polite.

Vasiliki also recounted seeing a Black man and a fit blond woman out jogging. “It was like I was in an American movie!” The soldiers’ diversity was a quality of the States I didn’t realize I had missed. As probably the only Asian-American in Alexandroupoli, I found it refreshing to see a non-Greek face, not least one that looked like mine.

The soldiers were here as part of Operation Atlantic Resolve in late November and early December, when Alexandroupoli hosted the largest transfer of United States military equipment through its port to date. The 1st Air Cavalry Brigade was arriving for a nine-month rotation in Europe with over 700 pieces of equipment, and the 1st Combat Aviation Brigade was heading home to Fort Riley, Kansas with about 300 pieces. The ARC Independence, a 228-meter-long green-and-white cargo ship, docked at the port’s container terminal for several days to transfer the hardware. It could be seen from across the port, towering over a wall of yellow, green and red shipping containers erected for security. Every day, news outlets and curious locals followed helicopter movements from the waterfront and covered the landing of army units at the Alexandroupoli airport.

I had the opportunity to spend several days inside the security perimeter to observe how Greek and American teams worked together to quickly inventory and prepare hundreds of military elements for transportation either back to the United States for service or onward to the Stefanovikeio military base in central Greece and beyond. I wanted to learn about the local impact of this latest milestone of US-Greek cooperation: what it meant for the future of the city and how it would benefit workers and businesses.

The positive reception Americans have received in this border town underscores how decades of anti-Americanism in Greece are giving way to a mutually beneficial strategic relationship.

A once and future transportation hub

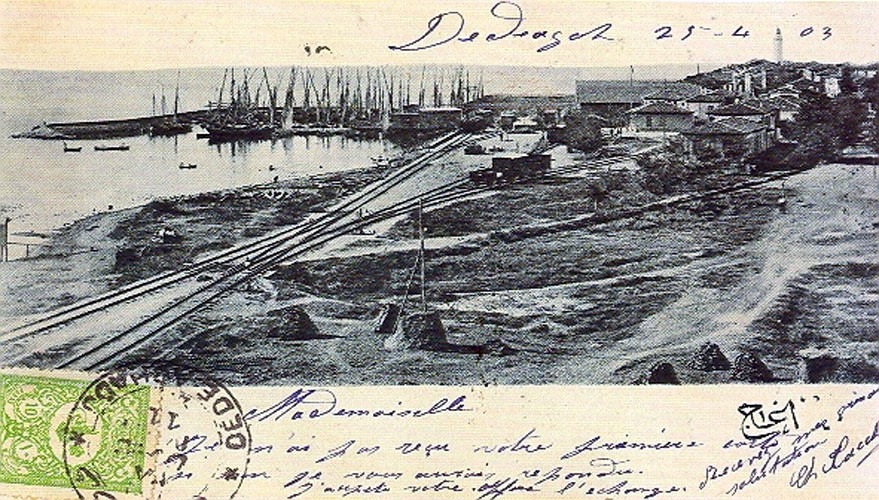

Alexandroupoli, the capital of the Evros regional unit and one of the newest cities in Greece, was first established as an Ottoman fishing settlement called Dedeagach in the mid-19th century. The city’s strategic location on a key land route between Europe and Asia, with an outlet to the Aegean Sea, made it an ideal transportation hub.

In 1869, the Ottoman Empire awarded a concession to Maurice de Hirsch’s Paris-based company Chemins de fer Orientaux to construct a railway network from Constantinople to Vienna. A branch of the main line connecting Dedeagach to Adrianople (modern-day Edirne) was completed in 1872. The route ended at the port to facilitate ship-to-train freight transfers. At the same time, the company Dussaud Brothers built the first port with a pier and an artificial mole to shelter boats and cargo barges from the wind.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the port and railway played a central role in the import and export of goods from the wider region of Thrace. The infrastructure soon transformed Dedeagach into a vibrant trade and administrative center with eight consulates and 18 banks and shipping agencies. Greeks, Turks, French, Austrians, Franco-Levantines, Jews and Bulgarians arrived to take advantage of new commercial opportunities.

Today, Alexandroupoli has a population of about 70,000 and all the comforts of a modern city. The sidewalks are wide and clean, unlike the tangle of Athenian streets, which are often upended by tree roots and left open for power or water work. The pace is slower, too, and there’s a strong sense of community.

A friend visiting from Athens was shocked to see cars and motorcycles stopping to let her cross the street. Since you can walk anywhere in about 10 minutes, it’s not unusual to receive spontaneous invitations for coffee or dinner. On nights and weekends, off-duty soldiers and police officers crowd the outdoor seating areas of the sleek coffee bars that line the main avenue. Locals take advantage of the red and green bike lanes, and in good weather, families stroll along the seaside promenade.

Konstantinos Chatzimichail, CEO of the Alexandroupoli Port Authority, grew up in the city and raised his family here. Not long after I arrived in October, we arranged a meeting at the port offices where he insisted I address him using the informal second-person singular. With his suit and aviator sunglasses, he seemed to exemplify the friendly, accessible tone of the city’s business class.

Chatzimichail comes from a family of businessmen. In 1974, his father founded the Interbagno Group, a one-stop supplier for the Greek military. “My grandfather worked with the military. So did my father, my brothers and my brother-in-law,” Chatzimichail said. “Our relationships are very close, almost familial.” Interbagno also equips energy and natural gas companies in the region. Chatzimichail still works for the family business. He told me he serves in his governmental role at the port without taking a salary.

He explained that as Turkey became a less reliable partner under Erdogan, the US military came to see Alexandroupoli as a faster, cheaper and safer alternative for shipments to Eastern Europe and the Black Sea than transport through the Bosporus strait in Istanbul. Alexandroupoli’s cargo terminal supports combined operations with direct links to the national and international railway network, as well as the national road system, while the airport is only five kilometers away. And unlike the better-known port of Thessaloniki, Alexandroupoli’s 500-meter-long cargo terminal pier is also deep enough to accommodate large ships.

This year, the port set a record for the transport of bulk cargo, mostly wheat—“the gold of Evros”—from northern villages exported to Italy. The authority loaded a ship with a capacity of 12,000 tons for the first time, creating work for truck drivers who had been unemployed during Greece’s decade-long debt crisis.

Bidding for the concession to operate the Alexandroupoli port for the next 42 years is currently underway, with the winner of the tender expected to be announced in February or March of this year. Of the four groups that submitted binding offers, two—BlackSummit and Quintana—are American. The third bid is from the French giant Bolloré in collaboration with the Copelouzos energy group and Goldair Cargo, and the fourth is from the Port Authority of Thessaloniki, a Russian-Chinese interest largely controlled by the Russian-Greek businessman Ivan Savvidis.

The port concession has geopolitical implications. In 2016, near the height of Greece’s financial crisis, the Chinese state-owned company COSCO bought a 51 percent stake in the Piraeus port outside Athens, which grew to 67 percent in October. The major shipping hub serves as a gateway to the European Union for Beijing’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative. Meanwhile, in northern Greece, Kremlin-linked Savvidis owns a 67 percent stake in the port of Thessaloniki. Winning the concession for Alexandroupoli could help the United States check its rivals’ growing influence in the eastern Mediterranean.

In addition to being a military and commercial hub, Alexandroupoli will also host major projects like a floating storage regasification unit that have the potential to transform the energy landscape of the western Balkans. I will focus on those developments in a future dispatch.

Chatzimichail believes that increasing operations at the port and railroad will eventually benefit the rest of Evros, bringing new businesses and well-paid jobs to the region and motivating locals to stay. “This infrastructure provides both security and development,” he said. “The work we’re doing now will safeguard Evros and the larger region for the next 150 years.”

Yet some are skeptical about how much developments at the port will affect the wider region, and at what price. “There are people who think that maybe the presence of the military on a more permanent basis will bring traffic to the market, to stores and restaurants,” Giannis Hionis, secretary of the Union of Private Employees of Alexandroupoli, Feres and Soufli known as “The Unity,” remarked during a protest rally held at the municipal theater. “But is there even one example where increased traffic was accompanied by increased wages or a general improvement in working conditions?”

Some opponents of the plans say Americans will turn the entire city into a base to serve NATO and EU “wolf alliances.” Others, like Angela Giannakidou, president of the Ethnological Museum of Thrace, fear the port’s development will come at a cultural cost, incentivizing people to leave their villages and accelerating the loss of traditions linked to farming and the land.

A center for US-Greek defense partnership

Meanwhile, increased US-Greek cooperation at the port has highlighted its geostrategic significance for the transatlantic alliance. In 2019, the US military put up $2.3 million to dislodge a sunken dredger named Olga from the port basin. The wreck’s removal enabled the United States and NATO to use the pier’s full capacity to support larger vessels. Since then, the port has hosted a steady stream of US military operations that have further tested its capabilities.

Alexandroupoli is one of the key areas shaping the bilateral relationship, Chatzimichail said. “We’ve built close ties with the US, not only at the country level, but also person-to-person. We’ve started to think in the same way and operate together. The friendships and partnerships we’ve developed here and the safe and welcoming environment Alexandroupoli provides has helped make the case for the port’s continued inclusion in the updated US-Greece Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement [MDCA].”

An October 2021 update to the MDCA signed by Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias and US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken extends the duration of the agreement to five years, enabling Congress to commit funds to modernize Greek facilities in Souda Bay, Larissa, Stefanovikeio, and Alexandroupoli. It also adds the city’s Giannouli military camp as an additional location for joint collaboration where up to 600 US troops could be deployed to assist with logistics operations at the port.

Winning the concession to operate the Alexandroupoli port could help the United States check its rivals’ growing influence in the eastern Mediterranean.

When the updated MDCA was signed, much was made in the Greek press of the guarantee in Blinken’s letter to Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis to “mutually safeguard and protect” sovereignty and territorial integrity against actions that threaten peace. After an especially tense two years in Greek-Turkish relations, many of the residents I spoke with believed the American presence in their city would help to stabilize the region and serve as a check against future Turkish provocations.

Although the countries are ostensibly NATO allies, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan pushed thousands of Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Bangladeshi, and Syrian migrants towards Greece’s land border in February 2020. At the same time, the number of Turkish fighter jets flying into Greek airspace, including over inhabited territory like Lesvos, Chios, Samos and Evros, broke records. And in the summer and fall of 2020, Turkey sent the survey vessel Oruc Reis into waters where both countries claim jurisdiction, raising tensions in the Aegean.

For its part, Turkey has accused Greece of playing the victim. Defense Minister Hulusi Akar claimed Athens is violating international treaties by keeping troops on the islands adjacent to Turkey that should be demilitarized. He also stressed that any extension of Greece’s territorial waters beyond the six-mile status quo would block Turkey’s access to the Aegean, constituting a casus belli. Akar characterized the MDCA as Greece’s “showing off” through a “futile” alliance within an alliance that only weakens NATO. And during November’s G20 summit meeting in Rome, Erdogan reportedly told President Biden that establishing a base in Alexandroupoli “bothers us and our people.”

The evening the ARC Independence docked, there was a rally at the municipal theater organized by the Greek Committee for International Détente and Peace and several trade unions based in Kavala, 150 kilometers west of Alexandroupoli, to protest the MDCA and, in particular, US use of the Giannouli camp. A statement issued by the organizers called on people to “kick out the butchers” and “disengage Greece from imperialist plans and wars.” The unions decried the new plans as part of “capitalists’ constant hunt for more and more profit.”

Savas Deftereos, a doctor at Democritus University Hospital and city council member for the municipality of Alexandroupoli, said in his speech at the rally that the city’s new infrastructure projects, including the Giannouli camp and the ring road, were designed to serve US forces. “These foreign soldiers do not guarantee our safety. Wherever the Americans have gone, they’ve created problems, sowed drugs, provoked bloodshed. Let’s remember Cyprus.”

Deftereos’ arguments recall US support for Greece’s military dictatorship and its position of equidistance during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, two main reasons for the anti-Americanism that until recently prevailed in Greece, especially on the political left.

But recent developments have done much to change mainstream attitudes. During the recent Greek debt crisis, the Obama administration worked to keep Greece in the eurozone, paving the way for a new era in bilateral relations. The left-wing populist Syriza government then in power strengthened ties with Washington, creating a bipartisan consensus that made it easier for the center-right New Democracy government to pursue policies like updating the MDCA when it took office in July 2019.

After the rally, a group of about 150 people marched down Alexandroupoli’s main avenue. “The only superpower is the people!” they chanted. Their voices brought me out to my balcony, and I watched them proceed in orderly fashion past my apartment building. Trailing a police officer on a motorcycle, they waved banners and flags while the city’s stray dogs ran alongside them. Another benefit of living in a small city: The protest was subdued by Athenian standards. Five minutes later, it was over.

Working with the Americans

Dimitris Karavassilis, the general manager of the Grecotel Astir-Egnatia hotel, was quick to dismiss the protest. “No one pays attention to those leftists,” he said. “They had to bring people from Kavala to increase their numbers.” He told me that the last mayor, Evangelos Lampakis, had tried to court Russian investors without success. “Historically, the Russians never helped Greece in comparison to the USA,” he said. “They tried to make contacts with the Russians, they saw that nothing happened, and now they see the Americans coming, which is a real thing.”

We were sitting in the hotel lobby just after Christmas, and throughout our meeting, Karavassilis rose many times to hug and kiss friends and to wish them chrónia pollá, or “many years,” an expression used during the holidays, but also for birthdays, name days and special occasions.

Originally from a small village 40 kilometers from Alexandroupoli, he studied in Italy and the United Kingdom and used to run European programs for rural and regional development in Evros. For two decades, he has hosted American officials at the hotel, and each time there are operations at the port, they book 20 to 30 rooms. During the visit of the ARC Independence, Karavassilis prepared a Thanksgiving dinner for his guests with a special menu.

“The Americans are excellent customers,” he told me. “Very polite, peaceful, they don’t create any problems, they have their own schedule, you give what you promise to give them and they accept and respect it.” The beachfront hotel, located at the end of the seaside promenade, is owned by the municipality. In addition to rent, 9 percent of the hotel’s annual revenue goes back to the city. “When they stay here, they are contributing to the community,” Karavassilis said.

Panagiotis Papadatos and his wife Sevasti Boi, who run the Piraeus-based transport and lifting company Cranes Arapis, have also worked with the Americans for over 20 years and serve as their main contractor for operations in Alexandroupoli. Panagiotis inherited the business from his father, Sevasti met him on a job and eventually came to work with him (“because she couldn’t stand to be apart from me,” Panagiotis said), and their son Giannis joined them as well. They described their company as a family, and constantly cleaned and cared for the space inside the security perimeter because during the operation, “it’s our home.”

Panagiotis recalled that the first US mission at the port was unprecedented for Alexandroupoli. “Sometimes we exceeded our budget because everyone saw the Americans and thought, ‘Here comes the dollar!’ The next time we came, they started to see us differently. They seemed more friendly, more professional. And as time passes, ship by ship, we get to know the locals, the port grows closer to the US military, and the dockworkers gain experience.”

Throughout the day, I often saw Panagiotis zipping from one place to another on an electric scooter, executing his plan to unload the ship as efficiently as possible. “With the Americans, each person does his specific job. Everyone has his specialty,” he told me. “The Greek does everything.” He gave an example of Americans calling a specialist to solve a problem while the Greek found the problem and fixed it himself. “Generally, Greeks don’t like to wait,” Sevasti added. “In the half hour you lose waiting, you could unload 30 vehicles.”

Donning helmet and vest, I descended into the belly of the ship to speak with stevedores as they lashed heavy vehicles to the floor with chains. They were solid, weathered men who smelled of cigarette smoke and teased each other while they worked. Many had labored side by side for 30 years. They don’t receive a steady salary but get paid only when ships dock at the port. Since there’s not a lot of work, the union can’t purchase new equipment and retiring stevedores are not replaced by new hires. Recently, the group has shrunk from 45 to 28 people, obligating Cranes Arapis to bring additional hands from Athens depending on the size and complexity of missions.

Anthimos “Mikey” Mousounakis, the president of the dockworkers’ union, told me that since US ships arrive every few months and not every day, they provide extra income but don’t offer the stability the workers desire. “As soon as the financial crisis passed and work started to increase, COVID came,” he said. The union hopes that when the port is privatized, its owners can make them salaried employees and bring more traffic so they can work every day.

A strategically located canteen

Two weeks before the arrival of the ARC Independence, a new American-themed canteen called Gorilla.gr Kitchen opened at the entrance to the port. Reminiscent of a retro drive-in diner with its neon lights and customers’ cars parked out front, the canteen features a hipster mascot and a quote by the American chef Anthony Bourdain below its service counter. A Greek and English menu offers hearty fare at affordable prices: an XXL Texas burger on brioche, warm sandwiches stuffed with cheese, french fries, and slow-cooked beef, pork or sausage. The generous takeaway portions are impossible for me to finish in one sitting, although I’ve seen dockworkers polish them off after completing a job.

Lefteris Chrysanidis, Gorilla.gr Kitchen’s 28-year-old owner, was born and raised in Alexandroupoli. He learned to cook from his father, who owns a restaurant in the nearby village of Aetochori, and, since 2013, has spent his summers working in hotels in Mykonos and Halkidiki. When he returned to Alexandroupoli this past fall, he had saved up enough money to start a business and settle down. “When you’re away, you gain money and experience, but you lose other things,” he told me. “I decided it’s better to stay here to be with friends and family.”

He’d been given the nickname “monkey, gorilla—maybe because of my face, I don’t know,” and used it to brand the canteen, choosing this corner to cater to customers at the port. “Every day, 100 to 150 truck drivers pass through these gates. Further back is the US military. And next to us is a store that sells construction materials. All these people come to me to eat.” When I shared my observations about the display and menu, he said, “The whole concept is American-friendly.”

Business is off to a good start. Lefteris has been selling 300 sandwiches a day, and the evening I spoke with him, he ran out of bread and had to turn away a group of teenage boys. He hopes to franchise the business in other Thracian cities like Xanthi and Komotini.

Lefteris’ canteen seems like a smart investment, perhaps the first of many inspired by US-Greek cooperation in the city. “The US presence has elevated the morale of local businesses during a ‘cloudy’ period,” said Leonidas Skerletopoulos, marketing and communications consultant at the Evros Chamber of Commerce. “It’s also important for the city to become more international and extroverted since the Balkan mindset is far from a growth mindset.” The chamber facilitated the visit by instructing business owners to admit Americans with COVID-19 vaccination cards even though they couldn’t be scanned by the Greek government’s verification app.

A few days after the ARC Independence departed, I found myself driving alongside line haul trucks carrying US military equipment across Thrace on Via Egnatia. I wondered if the drivers had stopped at Lefteris’ canteen to take sandwiches for the road, and if they had also transported the wheat that ended up in my delicious varvára. With the upcoming port privatization, one thing seemed certain: These weren’t the last trucks I’d pass loaded with cargo from Alexandroupoli.

Top photo: Alexandroupoli Port Authority CEO Konstantinos Chatzimichail (right, in suit with US-Greek flag lapel pin) at the Atlantic Resolve Distinguished Visitors Day with (from right to left) Chief of Hellenic National Defense General Staff General Konstantinos Floros, Defense Minister Nikolaos Panagiotopoulos and US Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt