CHANIA, Greece — I first visited Naval Support Activity (NSA) Souda Bay, an American military installation on the Akrotiri peninsula in western Crete, while working as the speechwriter for the US Embassy in Athens, when I facilitated former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s two-day trip to Thessaloniki and Crete in September 2020.

The trip had the orchestrated chaos of a flash mob. Hundreds of government officials, business leaders, diplomats, security forces and journalists converged on several sites for a few hours, each with their own stake in the secretary’s packed itinerary. In the public affairs section, we liaised with local reporters, organized the cultural program and worried over every detail of the optics, from the positioning of Greek and American flags to Covid masks and social distancing protocol.

NSA Souda Bay’s stated mission is to project power and warfighting capability in the eastern Mediterranean by providing logistical support, refueling and resupply services to US, NATO and coalition forces. Geographically, the remote forward operating station occupies the strategic central node where European, Africa and Central Command areas of responsibility overlap.

I drafted the secretary’s tweets for each stop on his itinerary, as well as complementary tweets for the State Department’s deputy spokesperson and Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt. I had often written about NSA Souda Bay for the ambassador’s defense speeches, and I used the three tweets to reiterate the embassy’s main talking points: that it is the “crown jewel” of US-Greece military cooperation, a relationship enhanced by recent updates to the countries’ bilateral Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement (MDCA), and its operations strengthen the NATO alliance and contribute to regional security and stability.

What I remember from that first three-hour visit to Souda Bay is largely impressionistic, limited to my own minor role in the proceedings. I arrived at the installation early and spent an hour in a holding room picking over a pile of American junk food. I remember the brilliant blues of the NATO Marathi Pier Complex, where Pompeo and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis boarded a Combatant Craft Medium boat used for special operations. And I stood on the sidelines in a Hellenic Air Force hangar while the secretary announced that the USS Hershel “Woody” Williams, a massive Expeditionary Sea Base ship assigned to US Africa Command, would be homeported at Souda Bay.

Some reporters saw the announcement as a show of support to Greece amid escalating tensions with Turkey. That summer, the Turkish vessel Oruc Reis carried out seismic surveys in waters disputed by the two countries, and a “mini-collision” of Greek and Turkish frigates in August 2020 brought the NATO allies near conflict. Two weeks before Pompeo’s visit, US Senator Ron Johnson claimed the United States was preparing to withdraw from Incirlik airbase in southern Turkey, and rumors were circulating in the press that one purpose of the visit was to discuss plans to transfer US military assets from Incirlik to Souda Bay.

While living on Crete this past summer, I wanted to revisit NSA Souda Bay to gain a fuller understanding of the US, Greek and NATO military facilities on and around the Akrotiri peninsula. What role has Souda played in the ongoing war in Ukraine? Did the 2021 update to the US-Greece MDCA result in upgrades to site infrastructure as promised?

After touring the installation and speaking with base commanders, sailors, journalists and locals, I was impressed by the facility’s close collaboration with its Greek hosts and its supporting role in the region’s most pressing conflicts. Indeed, since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war on October 7, the United States has deployed two aircraft carrier strike groups to the eastern Mediterranean to monitor the situation and deter Iran and Hezbollah from escalating it. The Greek newspaper Kathimerini reported that NSA Souda Bay was “on standby” to assist the strike groups. As regional instability necessitates a greater show of US and NATO force, Greece and the US may find opportunities to deepen their decades-long security cooperation at Souda Bay.

‘Premier installation of choice’

Roughly 18 kilometers from Chania, the capital of western Crete, NSA Souda Bay occupies a 1.1-kilometer strip within the Hellenic Air Force Base that is home to the 115th Combat Wing. Sharing an airfield with both the 115CW and Chania’s civilian airport, it is part of an ecosystem of Greek and NATO military installations that includes the Hellenic Naval Base in Souda; the NATO Marathi Pier Complex; the NATO Missile Firing Installation where allies test air defense, air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles; the NATO Maritime Interdiction Operational Training Center, which offers training in surface, sub-surface, aerial surveillance and special operations activities; and the new NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defense Center of Excellence.

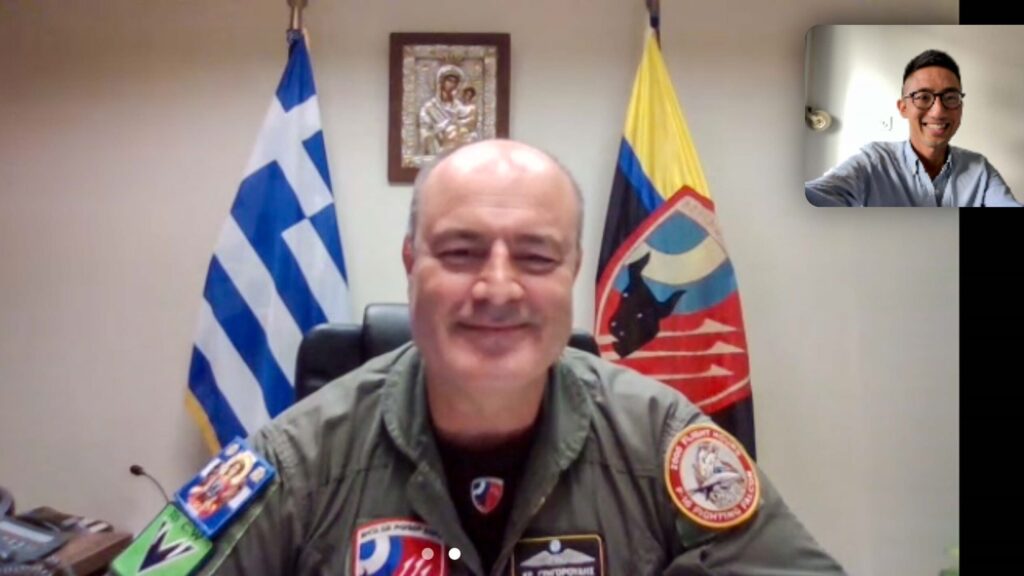

On a Zoom call, Hellenic Air Force Colonel Christos Grigoroudis, commanding officer of the 115CW, described how Souda’s location at the crossroads of Europe, the Mediterranean Sea and the Middle East gives the bay a unique geostrategic importance. “This area has been a key point for trade, energy and transport for centuries,” he said. Crete’s warm climate provides a comfortable year-round training environment. In addition, Marathi has the only deep-water pier in the Mediterranean Sea capable of berthing aircraft carriers like the two sent to support Israel.

Two weeks after the Hamas attack, Athens signed off on the construction of a new pier at the Hellenic Naval Base in Souda, part of a 188 million euro effort to expand and modernize the base so roughly half the Greek fleet can be stationed there by 2030. Commodore Nektarios Limperakis, commandant of the base, shared the thinking behind the decision. Compared to the Salamis naval base near Athens, where a majority of the fleet is stationed, “Crete is closer to hotbeds of unrest and conflicts that affect regional security, like Libya and the Middle East,” he explained. “Therefore, holding the Hellenic fleet in a strong forward position in Crete facilitates our role as a maritime security provider in the region.” Upgrading Greece’s second-largest naval base would give the fleet direct access to the eastern Mediterranean while relieving pressure from Salamis.

The collocation of military bases and installations facilitates collaboration and “provides extensive combined capabilities” continually used by the United States, NATO allies and partners, Grigoroudis said. “Souda is a very small place,” he added. “All the commanders are only a few kilometers away, and the actions of one facility may affect another. So we must be in close coordination.”

NSA Souda Bay was originally commissioned in 1969 as a 16-person naval detachment and became a naval support activity in 1980. Today, some 1,000 people including active-duty military, US civilian employees, contractors, family members and local Greek employees provided through the Hellenic Air Force work at the facility. It contributed some $158 million to the local economy in fiscal year 2022, including lease agreements and local purchases, local national employee salaries, concessionary sales, and service and maintenance contracts.

When I arrived for a visit, Public Affairs Officer Carolyn Jackson escorted me through two security checkpoints, the first for the Hellenic airbase and the second for NSA Souda Bay. The facility itself consists of pastel two and three-story buildings on either side of a single street, surrounded by a high chain-link fence. As we drove past a Liberty recreation center with its library and video game consoles, a Creamsicle-colored barracks building and a Navy Exchange minimart, I felt I’d entered a simulacrum of small-town, middle America.

Captain Odin Klug, commanding officer of NSA Souda Bay, met me in the skipper’s cabin, and together we took the “long walk”—as he joked—next door to the galley for lunch. The installation is small by design, he told me, which gives it agility and allows it to maintain a low profile. NSA Souda Bay is an unaccompanied tour of duty, meaning there are limited services for sailors’ dependents. There are no schools or childcare facilities on site, and many are deployed here on their first tours, as Klug was in 2006. He assumed command of the installation in July 2022.

In the serving line, he greeted colleagues and made an effort to speak to local staff in Greek. Over a meal of lobster tacos and chicken quesadillas, he said he felt language training was essential for developing relationships with local staff and community officials.

Klug wanted NSA Souda Bay to be the “premier installation of choice” for the US Navy and its allies and partners. “They choose whether or not to base aircraft out of here, whether they fly missions out of here, or sortie or bring ships in which can project significant power,” he said. “They could go to Palma de Mallorca. They could go to Malta. They could go to Split, Croatia. Why would they want to fight to come here?”

To help attract interest, the commander says he has focused on building and sustaining the installation’s readiness, prioritizing security, operations and most important, personnel. Since the base is shared with the Hellenic Air Force and hosts tenant entities that report to separate chains of command, he needed buy-in from many different stakeholders. That’s why understanding the locals and nurturing relationships at the municipal and regional levels have been important to him. A fan of extended metaphors, he described his job as pruning the branches of a tree so “everyone understands the way going forward.”

This past summer, as wildfires in central Greece triggered an explosion at an air force ammunition depot just six kilometers from the Nea Anchialos airbase, Colonel Grigoroudis requested NSA Souda Bay’s assistance to clear out brush from F-16 fighter jet magazines north of the Souda airbase. In early August, American sailors and their counterparts from the 115CW participated in joint live firefighter training exercises.

Since the eruption of war in Ukraine, NSA Souda Bay has also played an integral role supporting NATO and the US Sixth Fleet’s enhanced presence in the region, according to Vassilis Nedos, the political editor, diplomatic and defense correspondent for Kathimerini. This summer, the Gerald R. Ford Carrier Strike Group conducted operations in the Mediterranean Sea, part of the consistent carrier presence the US Navy has maintained there since December 2021, right before Russia’s invasion. Around the time of my visit, NSA Souda Bay hosted a detachment tasked with supporting the strike group’s forward operations in the Mediterranean.

Given the looming presence of a Russian fleet stationed in Syria, Souda’s logistics capability is “crucial for all these war games that are happening in the eastern Mediterranean, where we have submarines chasing other submarines and NATO warships monitoring where Russian destroyers and frigates are moving,” Nedos told me. NATO operations in the Mediterranean have become so routine since the start of the war, he said, that “it’s no longer news.” The strike group’s deployment was extended in October, and it was sent to waters near Israel.

Upgrades to NSA Souda Bay

Following a briefing in the skipper’s cabin, Klug and Jackson took me on a windshield tour of the operational side of the installation. Together, we drove onto the apron where aircraft are parked, refueled, loaded and unloaded. NSA Souda Bay shares the runway with the Hellenic Air Force and the civilian airport, and it can get busy in the summertime when there are many more commercial flights to Chania. The installation submits its flight schedule to the 115CW and communicates with them about arrivals, departures, local operations and movement from the apron to the runway or taxiway.

One of the first aircraft Klug pointed out to me was the State Department’s cone-nosed Gulfstream III, which is used for contingency medical operations not just within Greece, but around Europe, Africa and the Mediterranean. I remembered that Covid vaccine distribution through NSA Souda Bay was the reason our embassy in Athens was one of the first in Europe to get jabs in early 2021. Now I was looking at the plane that had transported the vaccines.

As we drove across the apron, Klug indicated bright yellow areas painted on the concrete. These contained hookups to an underground fuel hydrant system, a $6.5 million project completed in December 2021. Instead of bringing out a fuel truck, personnel can simply put a hose down, lock it into place and start refueling an aircraft. “A lot of thought goes into the process of future investment,” he said. “All this used to be unimproved earth.”

Before expanding the apron and adding the underground system, the installation conducted environmental studies to model how the project would be affected by earthquakes and temperature changes, and whether the ground could absorb enough water in the event of heavy rains. “Not only do we adhere to American universal facility code standards but we also act in concert with our Hellenic partners in the civil apron and the 115CW,” Klug told me.

In October 2021, the United States and Greece signed a second protocol of amendment to the Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement that has enabled US forces to train and operate within Greece since 1990. The update extended the duration of the MDCA from one to five years, consistent with other bilateral defense agreements between NATO allies. A big selling point of the deal here was that the longer term would allow Congress to make greater investments in Hellenic installations where Washington is authorized to operate military and supporting facilities, including Souda Bay.

The following month, the Hellenic National Defense General Staff (GEETHA) and US European Command (USEUCOM) signed an implementing arrangement to facilitate US-funded military infrastructure projects in Greece.

During my visit, NSA Souda Bay was abuzz with construction projects begun prior to the 2021 update. The largest was a three-story communications center that had broken ground last November. A tall crane stood over the site, and Captain Klug told me construction crews were getting ready to finish the second story. The $34 million project is scheduled for completion in fall of 2024. It will contain a telephone exchange, electronics maintenance shops, an electronic key management system vault and storage for equipment to be used by the installation. Klug sees it as a “facility for the future” that will affect operations for the next 10 to 20 years.

I also visited the air terminal, a white one-story building with the gloomy gray interior of a ’90s office building. It has a capacity of 170 people, but there are plans to replace it with a two-story Joint Mobility Processing Center, which will include an air passenger terminal, air cargo terminal, air operations, a naval supply warehouse and administrative spaces for the Red Cross and United Service Organizations.

Down at the NATO Marathi Pier Complex, new warehouse facilities are also in the works. In January 2022, NSA Souda Bay broke ground on a logistics support center that includes dry goods storage, cold storage for fresh fruits and vegetables, a mail processing center and logistics management offices. The $4.9 million center was identified as an “absolute need,” Klug said, and is expected to be completed in March 2024. A project to renovate Marathi’s sewage treatment plant is scheduled to begin in 2026. When complete, it will cut treatment time in half.

Locals’ reactions to the US presence

As a Greek-American child visiting relatives in Chania, Gregory Pappas, founder of the Greek America Foundation and publisher of the news site The Pappas Post, recalled seeing graffiti on the mole leading to the city’s iconic lighthouse that read “ΕΞΩ ΟΙ ΑΜΕΡΙΚΑΝΟΙ” or “AMERICANS OUT,” referring to the nearby installation at Souda Bay. While US support for Greece during its decade-long debt crisis largely ended the widespread anti-Americanism that had taken hold of the country since Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus in 1974, Greek parties of the far left continue to protest Greece’s involvement in NATO-led maneuvers.

The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and other groups staged one such protest last February, when the aircraft carrier USS George H.W. Bush stopped at the port of Piraeus before arriving in Souda Bay for a scheduled visit. Demonstrators called on the government to withdraw from “imperialist interventions” in Ukraine and eject NATO from Greek bases. In a keynote speech at the rally, Nikos Ambatielos, a member of the KKE’s central committee, criticized NATO for using Greece as a “bridgehead against other peoples” to serve capitalist interests, making the country a target for Russian retaliation. He decried what he called political games that have led Greece to arm itself against its NATO ally Turkey at the expense of the Greek people.

The KKE forms a small but vocal minority against the “expansion and upgrading of NATO bases” in Greece. While in Chania, I met with Deputy Regional Governor Nikos Kalogeris, who told me that 95 percent of Greeks don’t have a problem with NSA Souda Bay, while the 5 percent who object are mostly communists. “Others believe the base makes Chania a target, but I think it actually makes our region safer,” he said.

On the day parliament ratified the 2021 update to the MDCA, the KKE unfurled banners on the Acropolis that read “No to war. No to involvement. No to the bases of death.” The conservative New Democracy party, which had an absolute majority, approved the amendment with a vote of 181 to 119, while leftist Syriza, Greece’s main opposition party, voted against the update despite collaborating with the US while in power.

Most of the residents I spoke with on Akrotiri, who are in closest contact with Americans from the installation, appreciated and benefited from their presence. Giannis Kasimatis, the tall, personable owner of Irene Tavern in the village of Chorafakia, where many sailors and civilian employees rent apartments, remembered being treated to chocolates by an American couple when he was a kid. “The Americans have done good for Akrotiri,” he told me. “They rent houses. They spend at shops and restaurants. They donate clothes to local associations. They’re our friends, and for over 50 years, they’ve supported us and the region.”

Giannis’s grandparents opened the tavern as a small kafeneio serving his grandmother’s recipes in 1979. Growing up, he spent lots of time there and took it over in 2014. The afternoon I came for lunch, he moved from table to table, chatting with customers and surprising children with balloons. For dessert, he treated me to loukoumades, fried dough balls drizzled with chocolate and honey. “We’ve had American customers for years,” he said. “They love our food.”

I considered how a lifetime of interactions with Americans might have shaped this outgoing young man. He told me one of his relatives has worked in the galley at NSA Souda Bay for 20 years. I met her in the serving line the following day when I had lunch with Captain Klug. Giannis also mentioned visiting New York, especially the Greek neighborhood of Astoria in 2016, and I hoped the constant stream of customers from Souda had helped give his family some stability during the turbulent years of the Greek debt crisis.

“Stronger together” is a popular catchphrase for describing cooperation between NATO allies. But in Souda Bay, it seems to capture a truly symbiotic network of relationships that is likely to deepen given the ongoing conflicts in the eastern Mediterranean.

Top photo: The orchestrated chaos surrounding former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s visit to the NATO Marathi Pier Complex in September 2020