PAJU, South Korea — A water bottle filled with rice. A giant bottle of Tylenol. A dollar bill. A Bible.

One by one, Pastor Choi Moon-su placed these items on the wooden coffee table in his office. So far, he had shared very little about himself or his work. A kind but gruff older man in a characteristic bowler hat, he had directed me to sit while bustling around his book-filled office in silence, arranging materials before allowing me to ask him any questions.

But these four items gave me all the context I needed. Anywhere else, they might have seemed innocuous, but the church office where we sat was just a dozen kilometers south of the Demilitarized Zone, the region that has separated North Korea and South Korea for more than 70 years. For months, human rights activists have been sending these exact items—as well as surgical masks, media-filled USB sticks and anti-government leaflets—over the DMZ in packages attached to hundreds of large helium balloons.

The practice dates back to the Korean War, when governments on both sides scattered propaganda leaflets in enemy territory as a form of psychological warfare. Half a century later, in the early 2000s, North Korean defectors living in South Korea adopted the tactic in hopes of reaching ordinary people with anti-government messaging and Christian ministry.

“If you give one dollar, [a worker] can eat and live for a month. If a whole family shares this bottle of rice and makes porridge, they can eat for several days. Or, if a person sells it at the market, they can use the money to eat for six or seven months,” Choi said. “We are sending these balloons from a humanitarian point of view. What the North Korean defector groups are now doing is the sort of work a pastor must do.”

The work has never been popular with North Korea; in 2020, the government even blew up an inter-Korean liaison office building close to the DMZ in retaliation for the anti-government leaflets. This spring, stopping the balloons once more became a top priority for North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

On May 28, the North Korean government kicked off its tit-for-tat response to the activists by launching its own balloons—but rather than aid or propaganda, they carried bags of trash. Since then, more than 3,300 have landed in South Korean territory, dumping at least 15 tons of paper, plastic, cloth, soil and even human and animal waste. The balloons have disrupted flights, sparked fires and caused upwards of 100 million won ($74,600) in damage. One even fell in front of the South Korean president’s office in the central Seoul neighborhood of Yongsan, heightening security concerns.

The South Korean military has harshly criticized North Korea for this “despicable and irrational provocation,” which it deemed an “inhumane and crass” violation of international law. But in the country’s legislature, representatives of the two major parties—the conservative People Power Party and liberal Democratic Party—have been caught up in a debate over the impact of the activists’ work on Korean security and the potential limits of free expression.

“Why did trash balloons come from the North? It’s because the South scattered leaflets against the North,” National Assembly member Seo Young-kyo, a member of the Democratic Party, said during a legislative meeting in June. “We should have dialogue, not a confrontation between powers.”

For years, supporting the defector-led groups seemed like a no-brainer to me. From 2017 to 2020, I had worked at the Human Rights Foundation, a New York-based advocacy group, where part of my job had been to promote a program collecting USB drives that would be filled with media and smuggled into the North. Under international law, North Koreans have a human right to access information, and many defector activists have attested to the impact foreign media had expanding their world views while they still lived under the Kim regime.

But now that I’m in South Korea, I have a chance to better understand the domestic debate around balloon launches and leafleting in particular. And it has perhaps no clearer expression than in Paju, the midsize city that is home to Choi’s Nambok Jungang Church.

Weeks before the hot summer day of my visit, activists from the high-profile group Fighters for a Free North Korea had gathered at night to launch their balloons near the church. They were interrupted by Paju’s liberal mayor, Kim Kyung-il, who “strongly protested and confronted” the group, according to the liberal news site Hankyoreh. After an ensuing scuffle, during which Kim claimed he was threatened with a wrench, the group’s members scattered. They’d given up on the rest of the evening’s launches, but that wasn’t enough to ward off criticism. The next day, a few concerned citizens began picketing in the church garden to oppose sending any more leaflets to North Korea.

Kang Yeong-do, Kim’s head of media relations, explained that the mayor had disrupted the balloon launch because of a sincere concern for citizens’ well-being.

“Because the safety of citizens is his first priority, the mayor tried to block [the balloon launches] with his own body,” Kang said during an interview in Paju City Hall. “When he travels around Paju City, everyone he meets holds his hands and tells him the leaflets can’t fly because they can’t live with the anxiety. There are many older people that plead with him this way.”

Kang explained that citizens of Paju are also worried about the effect the balloons could have on the local economy, especially on the tourism industry and farms near the DMZ.

“If the relationship with North Korea worsens, tourism in Paju will stop,” Kang said. “We have to have some peaceful flow between the South Korean government and North Korea in order to stably plan for our futures.”

Historically an agricultural and military city, Paju is best known today for its DMZ tourism. Its various attractions and districts branch off from expressways with thematic names like Freedom Road and Peace Road. But over the past few decades, the city and surrounding Gyeonggi province have invested significantly in diversifying their economies. These days, Paju is home to many South Korean publishing companies and has been attracting attention as a potential hub for high-tech manufacturing.

A short commute from Seoul, Paju seems notably slower-paced and friendlier, with older Koreans taking an interest in tourists like me, striking up easy conversations at the bus stop. The city’s downtown is packed with restaurants and pharmacies, but nearby, low-rise buildings yield to rice paddy terraces, corn fields and fresh furrows.

Under former President Moon Jae-in, Kang said, a general “atmosphere of reconciliation” had relieved anxiety in Paju and eased development planning. As a liberal politician, Moon had revived the Democratic Party’s “sunshine policy,” favoring a more conciliatory, persuasive approach to relations with North Korea’s hot-tempered leaders. That had included passing a law in 2020 to criminalize leafleting and balloon launches.

However, in September 2023, South Korea’s Supreme Court found that the 2020 law constituted an excessive restriction on free speech. The decision kicked off a huge wave of activist balloon launches in the first half of 2024 and made it significantly harder for their opponents to legally restrict their activities. Hoping to gain some control back from the activists, Democratic Party politicians in Paju and Gyeonggi have been pushing to establish “risk zones” near the DMZ that from which the local authorities can block activists. So far, the measure has not passed but after a new flurry of balloon launches in early September, Gyeonggi’s Special Judicial Police reportedly began patrolling border areas to keep an eye on activist groups.

“It’s not that people feel anxious because of the balloons that are sent from here but because North Korea is sending trash balloons and missiles and drones,” Choi said. “Paju’s mayor should officially condemn North Korea and tell them not to send balloons.”

The question of how to handle relations with North Korea is one of the most polarizing issues that separates the two major parties. Where the Democratic Party prefers “sunshine,” the conservative People Power Party prefers a more oppositional, hawkish approach. Its members generally tolerate or even support activist balloon launches; this summer, various state officials said they have left the activists alone because of respect for the Supreme Court decision.

But the public does not seem to be as polarized when it comes to the balloon conflict. Every time I’ve brought up the trash balloons in casual conversation, people have responded with scoffs and laughter, dismissing the campaigns as childish or ridiculous. That fits with an overarching impression that most South Koreans do not think about North Korea-related issues often, preferring to focus on domestic political issues that affect their day-to-day.

Nevertheless, when surveyed by Gallup Korea, a majority of South Koreans supported greater restrictions on the activist groups, with 60 percent saying the government should stop them from distributing leaflets and only 30 percent saying they should not be stopped. Despite their representatives’ preference for noninterference, People Power Party supporters were evenly split on the issue.

The public is less opposed to other forms of psychological warfare. In June, in response to the trash balloons, the government resumed broadcasting propaganda messages through loudspeakers near the DMZ, another practice that had stalled during Moon’s tenure. In Gallup’s surveys, 55 percent of respondents supported the government broadcasts, while only 32 percent disapproved.

Daniel Connolly, professor of international relations at Korea University, explained that while defector activists are typically portrayed as “heroic figures” in Western media, the South Korean public may be more wary because of the diverse groups involved in the work and the differing justifications for their activism.

“They really put an emphasis on the humanitarian aspect of their balloons,” Connolly said in a phone interview. “But really, they have different standards for public diplomacy. Some are attempting religious conversion, some political overthrow, and some may be just trying to share news about South Korea or South Korean media. It’s many different actors with different perceptions of what they want to do to North Korea.”

“These subtle currents may make some South Koreans a little skeptical of these civil society actors,” he added. “South Korean citizens are probably much more confident in the state’s ability to turn on or off these broadcasts in a responsible way.”

The diversity of content and style is a point of contention among activists, too. Seongmin Lee, director of the Human Rights Foundation’s Korea desk, explained that many defector-led groups are privately critical of groups like Fighters for a Free North Korea for soliciting media attention with public balloon launches.

“By doing it publicly, they could get more chances of fundraising. I think that is understandable in many aspects,” he said. “But some people are very critical of these operations. There are certain things that need to be done in a discrete way”

“At the end of the day, our goal is not to create controversy [or] a security risk along the borderline [or] to provoke the North Korean regime” Lee added. “Our goal is to help North Koreans get to know their situation better [and] get to know the outside world. Through that, we hope they can make a decision about their future for themselves.”

Despite the legislative debates, the activists I spoke to said it’s important, now more than ever, to continue reaching out to North Korea’s people. Since the start of the Covid pandemic in 2020, Kim Jong-un’s government has tightened its borders and passed a flurry of new regulations cracking down on the free movement of people and information. As a result, North Koreans are more cut off from the outside world than ever before. Recent escapee testimonies have reported that the authorities have even resumed public executions for sharing and listening to Korean pop music.

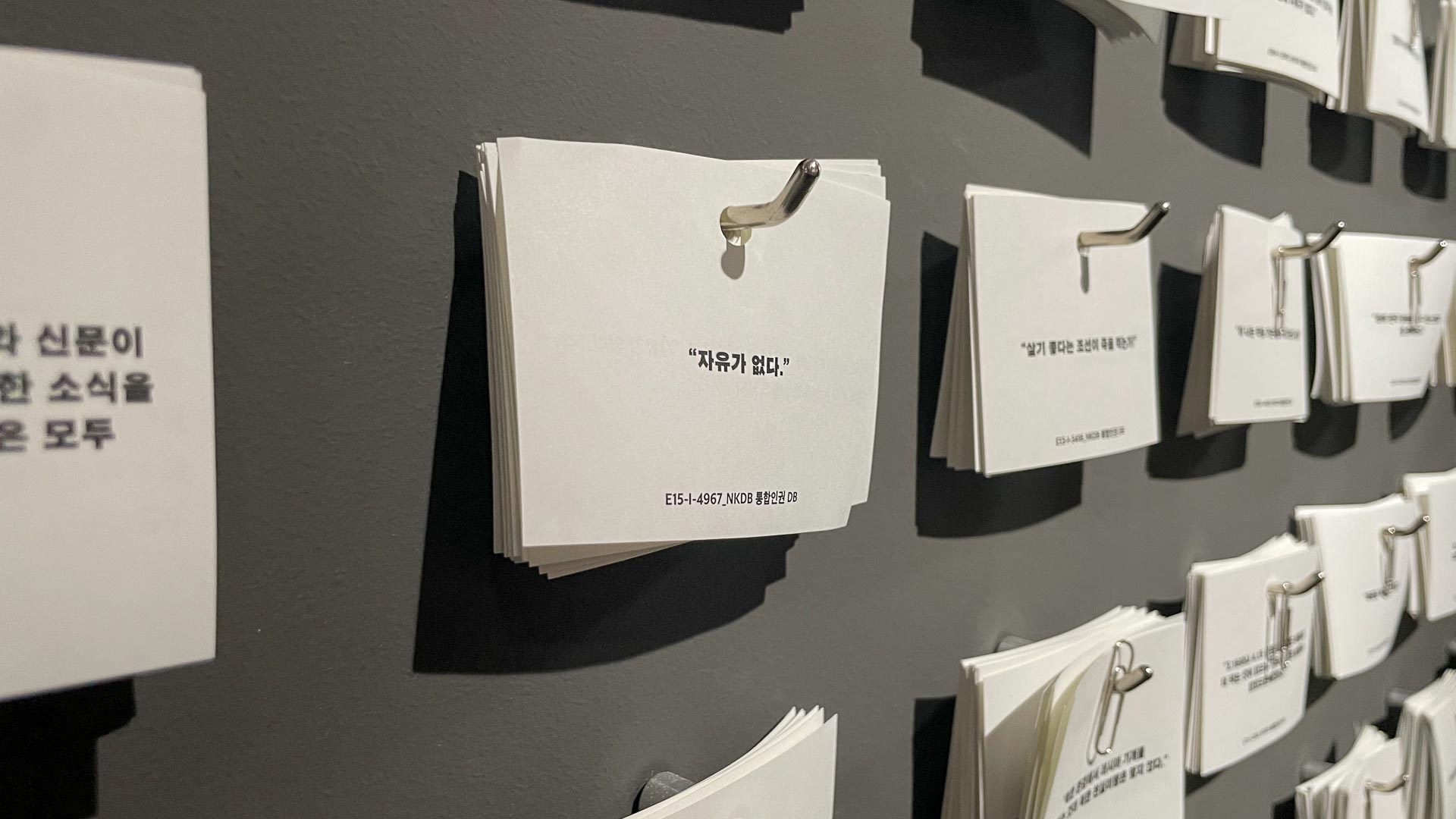

“The North Korean government knows how much information—whether it’s political, whether it’s historic, whether it’s just a South Korean drama—changes the way the North Korean people see not just the regime but also the outside world,” Hanna Song, executive director of the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, said in a phone interview.

She believes the fact that the regime reacts so strongly to the work of a “small number” of activists demonstrates the potential impact of their work. “Whether we agree with their method or not,” she said, “information really is something that will change North Korea eventually.”

In the short term, banning the activists’ balloon launches seems unlikely to improve security on the Korean peninsula, where relations have been steadily worsening. In January, North Korea stated that peaceful unification with the South was no longer possible, and since then has carried out a schedule of military actions designed to ramp up tensions, including GPS signal jamming, missile tests and a failed spy satellite launch. The balloon warfare fits into this much broader picture, allowing the Kim regime to vex its adversaries without provoking an escalation.

Still, the balloon debate offers insight into complexities I was too quick to brush aside in the past. As a human rights professional, it was easy to sort the world into good and bad actors, and deem anyone who opposed the activists as callous. But Paju’s citizens showed the impact smaller fluctuations in tensions can have on their sense of safety and financial futures. Understanding those concerns is crucial to better activism and policymaking.

Top photo: Ribbons convey South Koreans’ wishes for peace and unification on the barbed wire fence in Imjingak Park in Paju, a DMZ tourist and memorial site