With a wild screech, a monkey springs from the trees and grabs our backpack. The pack sits unattended on a bench, but within a few feet of my hand. The monkey knows to grab the straps. But it miscalculates the weight of the pack and cannot leap back into the trees from the bench.

My husband Josh spins on his heel so that their noses meet only inches apart. The beige-faced monkey searches Josh’s tan face, then opens his mouth with a hiss, baring his teeth. Josh opens his arms wide to both sides and yells. They pause in space together, two primates separated only by a bag and a few million years of evolution.

I could step forward to also defend the backpack, but the interaction mesmerizes me. (Also, the monkey is a little intimidating.) Josh towers over the monkey, which moves its head up and down in quick jerks as it looks for evidence of his foe’s seriousness. I’m pretty sure the monkey can’t lift the bag, but I’m not sure that it won’t attack Josh, and I start to move. The monkey swivels, breaking the pause, and, with one hop and a scream, jumps into the trees overhead. The jungle turns into a cacophony of banshees and the whooshing sound of branches bending and leaves shaking under a troop of savvy thieves.

As we peer into the forest canopy, the attempted thief returns on a tree limb with a complete family size package of Oreos. That’s right, Oreos. It sits on the round branch and tears into the plastic. Each small package of four cookies it breaks open like a nut, using the tree as an Oreo-package-cracking tool. It opens the two cookie halves and licks out the white filling. But what happens next makes my jaw drop: once it scrapes the sugary filling clean, the monkey drops the two cookie pieces to the jungle floor without even watching them go.

I laugh out loud under the leafy canopy of Manuel Antonio National Park. So many tourists wander this tiny, 680 hectare park that these monkeys have not only stolen plenty of junk food, they have learned how to get their favorite calories. This forest thief presents as a wild animal to the tourists, but busily consumes junk food. It’s still a real monkey following its instincts to survive—but I have to wonder about the long term health of this monkey that won’t even eat the cookie part of an Oreo. I hope this isn’t a forest of diabetic capuchins.

I’ve been wary of the monkeys, and this guardedness is reflected in all my interactions in general in this country. Costa Rica created a wildly successful brand for itself as THE ecotourism destination. Preserved land takes up 25 percent of the country in a combination of national parks and private reserves. In addition, the country pledged to be carbon neutral by 2021. As a lifelong traveler dedicated to climate research and sustainable forest and ocean conservation, that should make me their best customer.

Instead, I arrived skeptical. I just didn’t see how the hype could be real. Turns out, some of this was justified, and some of it wasn’t.

What’s Real in Costa Rica

From the sea, the first shockingly noticeable thing about Costa Rica is the forest. Steep cliffs plunge into the Pacific, the land clad in a forest so dark green it looks like pine slopes instead of jungle, a mark of tropical dry forest (which still feels very, very wet in the rainy season.) Almost exactly at the Nicaragua border, rolling brown fields give way to steep green cliffs that plunge into the sea. We don’t see a single house or structure on shore for the first 50 miles. This is Santa Clara National Park, jutting into the Pacific. It’s in Guanacaste province, which is known for its culture of cattle and cowboys, but a large chunk of land is still set aside for forest.

The first national park in the province led an international trend in the mid-1980s. University of Pennsylvania biologist Daniel Janzen proposed that parks could only survive with “happy people” living around them. So when Guanacaste National Park set its boundaries, Janzen, who worked in Costa Rica for decades, invited local ranchers and their cattle to remain in the park, and they were trained and paid as park staff.

This ended up being one of the guiding principles of ‘ecotourism,” which had emerged in the 1970s with the worldwide environmental movement. Standard tourism ignored the needs of local people and environments by disregarding pressures on the land, coast, and sea, while profits funneled to foreigners. But the new ‘eco’ version strove to include the wellbeing of local people and natural systems.

Thus from the sea, Costa Rica appears dramatically different than the rest of Mexico and Central America, a “Rich Coast” indeed. Even though the country was named by Christopher Columbus when he stumbled onto the Caribbean shore in 1502 for the metal riches he (mistakenly) thought he would find within, the country has come to honor its rich diverse biological resources. In Mexico, houses crowded the beaches and lined the arid shores. In Honduras and El Salvador, shacks peppered the ocean slopes, hillsides with only a few trees clinging to crumbling, deforested land. Nicaragua’s pastoral slopes showed grazing and farmland, despite 20 years of searing droughts.1

But Costa Rica’s slopes are untracked green, so dark and thick they appear black from the ocean. Dropping the anchor in Playas del Coco to ‘check in’ to the country, we scan this supposedly popular beach. No restaurants line the beach—only leafy mangroves trees and palms. When we row ashore, we discover that the restaurants exist, just set back and cloaked by foliage.

“Well, we have laws that protect the coast,” my friend Wilson Rojas tells me. Wilson grew up in a rural town near the Pacific coast, and despite his father’s insistence that he never learn English, he taught himself. After years in the hotel business, he started his own shuttle company, and we have hours to talk when I’m on my way to the airport. I explain to him that in other countries we’ve visited, laws don’t translate to enforcement. But Wilson states law as fact, as opposed to political suggestions.

This brings me to one of the most delightful and real aspects of traveling in Costa Rica: environmentalism pervades the national consciousness. Because of Costa Rica’s push to court ecotourists, it’s part of the “self-identity,” as Chris Wille from the Rainforest Alliance puts it—from the taxi drivers to President Luis Guillermo Solís.

In addition, the outrageously hardworking architect of the most recent climate negotiations in Paris was Christiana Figueres, daughter of the former president and revolutionary Jose Figueres Ferrer. The father is a national hero, the man who abolished Costa Rica’s military after the civil war in 1948, and granted universal suffrage; his daughter boldly followed in his footsteps, internationally championing the environmentalism that Costa Ricans embody.

In this way, ecotourism’s definition as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and improves the welfare of local people”2 seems to line up with Costa Rica’s push for equality that began in the middle of the 20th century.

Booted by Ethical Traveler

Yet Costa Rica has struggled in the past with the realities of ecotourism, and it does so again now.

In the mid-1980s, Costa Rica’s Institute for Tourism (ICT) offered incentives to investors to develop ‘eco’ tourism. However, most local people with limited resources couldn’t utilize them: the incentives only applied to hotels or lodges with 20 rooms or more. Large international hotel chains popped up along the coast and cashed in on the budding green reputation of the country, but their build and practices supported neither the local economy nor natural environment. By the early 1990s, experts estimate that foreigners owned 80 percent of the coast.

However, many families were still able to move into ecotourism as the industry expanded at 17 percent per year in the first half of the 1990s. From butterfly farms to restaurants, horseback rides to a few cabinas, local families could nose into the tourism trade and benefit from the boom. Most recently, increased non-stop flights from the US and Europe fuel the ecotourism expansion.

Beginning in 2009, Costa Rica was named one of world’s ten best ethical destinations by Ethical Traveler, a San Francisco-based non-profit organization founded in 2003 by travel writer Jeff Greenwald. The organization is dedicated to finding countries in the developing world that strive for and implement those original concepts of ecotourism: human rights and environmental preservation. (Ethical Traveler also added animal rights to the qualifications for their ranking in 2013.) Costa Rica has mostly remained on the list. But in 2014 and again in 2015, Costa Rica didn’t make it. Despite hosting Greenwald in the country, Costa Rica was excluded again in 2016.

Ethical Traveler cites ongoing, unresolved issues with shark finning, sea turtles (and the people trying to protect them), and consistently debasing and sometimes violently removing indigenous peoples. Although Ethical Traveler doesn’t specifically mention it, issues with indigenous rights are wrapped up with the question of building new dams and the specter of climate change.

The Trouble with Turtles

“You’ve never had a turtle egg?” Oli looks at me incredulously, and I’m pretty sure I return the look. It’s like asking me if I’ve ever hunted an elephant. Nearly all species of sea turtles are classified as Endangered, and I used to work with a non-profit organization that partners sea turtle biologists with high school students in Costa Rica to protect Leatherback turtle nesting sites near the Pacuare River. Between snaring fishing nets, plastic masquerading as food, and the illegal trafficking of turtle meat and eggs, sea turtle populations worldwide have declined by an estimated 95 percent.

“Well, turtle eggs taste just like iguana eggs.” Oli turns down the corners of his mouth and shrugs, implying that I’m not missing anything.

Of course, I’ve never had an iguana egg either, so I can’t help but laugh. He also thinks it’s pretty funny that I have never had an iguana egg. I ask if they taste like chicken eggs. He contorts his face and tells me that, no, they’re gross. More…slimy.

Oli, Josh, and I have become good friends in our short time on the central coast. Oli’s enthusiasm for life is as infectious as his smile. Both he and Josh share a love of naturally-built treehouses and simple living, and he’s in the process of building his own unique ‘treehouse.’ We are mutually inspired by each other’s lives, and I feel like Oli treats us like family. He rarely has an afternoon or day off from his job as butler at a very high end villa, and we usually only see him for a beer. But he’s told us that his lifelong dream is sailing the world, so today we catch him for a sail after work.

However, he’s been turning pale and uncharacteristically quiet. Although he’s spent plenty of time at sea in small boats, the motion of the swell rolling under our keel is too much for him. We’re used to it, but the pitch forward as the swell catches us, and the way the boat falls off the back of the wave as it wobbles side to side, is not for the faint of stomach. He never complains, and keeps telling us how great this experience is—all while sinking further and further into his chair. I know that sink, the maybe-if-I-melt-my-stomach-into-the-boat-I-won’t-vomit move.

Before the sea manages to silence him, he tells us about his dad, who is from the city of Limón on the

Caribbean coast. He ate hundreds of turtle eggs a year. They’re purported to be an aphrodisiac, a performance enhancer for men (scientific research negates this.) Oli talks about this openly, giving us a glimpse into a normally forbidden topic.

“It was a huge part of the culture over there.” More quietly, he murmurs, “Still is.”

Sea turtles have been protected by the national legislature in Costa Rica since 1966. But eating sea turtle eggs is a bit like the machismo associated with playing football in the US. It takes generations to remove a cultural norm from the lexicon. People fight hard for its preservation, no matter the damages wrought. Eating turtle eggs, despite protection and dwindling numbers, is part of a larger coastal culture, especially on the Caribbean coast.

In the last decade, another ominous issue has melded with turtle eggs: the complex world of drug trafficking. Turtle eggs are relatively easy to collect, and at one dollar each, a few nests of 100 eggs are easy pickings for poor fishermen out of work. Many of the eggs now pass through similar trafficking circles as drugs.

In 2013, Jairo Mora, a 26-year-old volunteer, walked Costa Rica’s Caribbean beach at Moín, just like he had the two previous years. He walked the beach to protect turtles and turtle eggs from nighttime poachers. Mora is part of a new generation in Costa Rica, young people raised with environment at the center of their culture (instead of turtle egg-eating.)

Crime-ridden Moín beach is a nesting ground for critically endangered Leatherback sea turtles. These turtles may live over 100 years, and they don’t keep track of the political climate or crime scene when they are ready to have babies. Leatherback turtles often return to the same beach where they hatched or, unique among sea turtles, find a beach with soft sand (to protect their carapace, which is soft and leathery.) They drag their sometimes 2,000 pound bodies ashore at night, dig a hole in the sand, and lay around 100 eggs in this ‘nest’ that they then re-cover with sand. If the eggs are not found and eaten by anything from crabs to coatis, they’ll hatch in 20 days and face the dangers of the open sea.

At Moín beach, Mora directed the efforts of Widecast, now renamed LAST, a volunteer organization which attempts to protect sea turtle eggs throughout Central America. This work became increasingly dangerous in 2012: Mora and other volunteers were held at gunpoint on the beach. Mora’s boss at Paradero Eco-Tour, a state-sponsored animal rescue group, had to relocate from Limón to San Jose as the death threats increased. Despite mounting danger, the headstrong Mora refused to be cowed, and he developed a local reputation for his fierce defense of the turtles.

For the 2013 nesting season, police stopped protecting Mora and his volunteers on their nightly beach walks, leading journalists to suspect that the local government, police, and drug traffickers had reached a new level of coziness. But, in the company of four international volunteers, Mora went to the beach anyway on the night of May 30th. His car was overtaken by five masked men when driving away from the beach. The four volunteers eventually managed to escape their abductors, but Mora’s body was found the next morning on his beach, naked and beaten.

Until March of 2016, no one was convicted. The international environmental scene was outraged at the suspiciously slow action and poorly conducted trials. As I read about the bungled case, with the government’s lukewarm response, inaction, and floundering, I found the proceedings remarkably similar to those in Mexico, a country renowned for its government corruption. I wondered about the ties between drug traffickers, local, and national government.

In its failure to deal swift justice in Mora’s trial, Costa Rica showed its internal crisis that had, until this time, been hidden from popular international view. Environmentalists couldn’t be safe on a coast ruled by drug traffickers in bed with local government. But with Mora’s disgustingly tragic case, a harsh spotlight shone on Costa Rica in a new way. And Ethical Traveler noticed.

No Sharks

We haven’t seen a shark from our boat since Mexico. Normally, we see them as a fin cruising at the surface. It’s not like Jaws: they often don’t appear to be in any rush, just hanging out at the top of their world. Sometimes we can see their tails languidly swishing side to side. Sharks are at the top of the food chain, a so-called apex predator that plays a crucial role in maintaining the health of their natural ecosystems.

We are only one boat, so I can’t know with certainty why we haven’t seen them: climate change, lack of food—or lack of sharks. We have seen many fishers with sharks in their boats, yet the finless bodies of sharks clutter certain docks and beaches, left to rot.

The fishermen we usually meet along the coast of Mexico and Central America are noticeably absent as well. On the central coast, in Quepos, an American-owned marina dominates the shore, and the fishing pangas enter and exit the estuary here, separate from shore and difficult to access from town.

In general, the fishers on the central Pacific coast feel forgotten in the tourism boom. In Quepos, the head of a fishing cooperative led a protest this summer calling for more government attention. The monopolistic fish buyer for the area imposes inconsistent and unfair pricing, they argue, making fishing an even more difficult job than normal.

With depleted fish stocks from overfishing and waters warmed by El Niño driving away many ocean species, some of the younger fishers have fallen prey to drug traffickers increasingly using the Pacific coast to run cocaine to the US. The traffickers pay up to $25,000 for one run, and the fishers, who know every nook of the coast, are their lackeys. Last year, seven Costa Rican men with no previous criminal records were arrested for drug running on the Pacific coast.

But for those who haven’t made the cut into tourism and aren’t willing to risk the drug trade, one of the most lucrative fishing practices is driven by the quest for another supposed aphrodisiac from the sea: shark fins. Costa Rica not only bans shark finning, but requires that the fins be partially or fully attached to the shark carcass in most fisheries.

However, there is no ban on shark fishing. Fishers throughout the coast know the high market value of just one fin, around $120. For someone living off $200-300 per month, the average take home pay for fishers in the Quepos area in 2016, one fin can make a huge difference.

This economic struggle echoes all the way up to the top of the government in Costa Rica. In 2015, President Luis Guillermo Solís said his government would lobby shipping companies to unravel current shark fin shipping bans, and “work to weaken shark protections.”

With these pledges, Costa Rica falls further away from its “green” reputation—and off the Ethical Traveler Top Ten for the third year in a row.

Profit from Every Dwindling Drop

Nearly every cab driver in Costa Rica tells you that their country will be carbon neutral by 2021. They state this with the same assuredness and pride they seem to feel individually about the country’s land conservation and their nation’s reputation therein.

However, at the Conference of Parties (COP) climate talks in Paris last year, Costa Rica quietly backed off of this claim, saying instead it would meet that goal by 2085. Costa Rica’s transportation sector uses 70 percent of their country’s total petroleum, and this accounts for 40 percent of the country’s total emissions—so their decision is driven in part by this sector.

I think about this from the passenger seat of Oli’s Suzuki Samarai as we roar past miles and miles of African palm oil plantations to get to his house. Oli can’t afford to own property in Manuel Antonio where he works, so he commutes 45 minutes per day and lives miles away from the coast, behind a sprawling oil palm plantation.

On the roadside, thick black smoke rises out of a stack at a plant processing the palm oil, and I wonder if these emissions get added to Costa Rica’s total. The United Fruit Company introduced these oil palms in Queops during the banana blight in the 1940s, and the industry has since grown wildly, to the point where the government finally yielded to political pressure in 2015 to enact a moratorium on new palm plantations. But no one sees the industry releasing its landgrabbing and sooty hold on the country any time soon.

We drive a terrible, rutted dirt road through a maze of monocrop oil palms to finally emerge at the foot of the Tarrazú mountains. On Oli’s only day off he’s offered to show us his ‘farm,’ about a quarter of an acre of remarkable self-sufficiency. His octagonal house, made with local teak and twenty feet off the ground, hovers over his well that he naturally filters with charcoal, sand, and gravel inside the cylinder. Chickens and ducks waddle around us, and pigs snort through the organic garbage.

“One hundred percent grasshopper fed,” Oli grins, picking up a chicken thoroughly annoyed by the disturbance in her cozy roost. I nearly cried with delight when he sent me home with a dozen eggs. (They were the richest chicken eggs I have ever eaten.)

Oli proudly shows us his one solar panel and a battery. All he needs it for is his water pump (he has a full bath in his second-story octagon) and two lights. But most people don’t live like Oli: they are connected to the national electricity grid.

Costa Rica gets most of its electricity from hydroelectric dams, some geothermal energy, and limited wind and solar. In 2015, Costa Rica claimed to meet one hundred percent of its energy needs from these sources for a record 113 days.

But the timing of this event provides the hint to the lack of sustainability of this feat. 2015 was an unusually wet year for the country (thanks to a climate change-fueled El Niño), which provided extra water for the dams. These renewable days only happened in the wet season. The rest of the year, to fuel the difference in demand as dams lose their power, Costa Rica relies on one of the dirtiest types of energy: imported coal.

According to ICE, Costa Rica’s government-owned energy company, dams typically provide 70 percent of Costa Rica’s power needs. In September, Costa Rica inaugurated the largest dam in Central America, the $1.4 billion Reventazón dam. Reventazón is Central America’s second largest public infrastructure project in history, only surpassed by the Panama Canal. Once all five turbines are powered up, it will be able to generate 305 MW, powering 500,000 homes. The 130-meter-high dam floods 6.9 square kilometers and has created an 8-kilometer-long lake.

The Reventazón dam disrupts one of the only remaining wildlife corridors for endangered species, including the jaguar, in Central America. The dam project committed $1.6 million to reforesting some of the scars in an attempt to patch together the corridor—but this serves a larger purpose to try to keep the loose sediments of the area from sloughing in and refilling the lake. The reservoir, roads, and traffic ensure the corridor has been sliced apart. Disrupting this corridor is no small potatoes for a country that hangs its reputation on caring for its wild ecosystems.

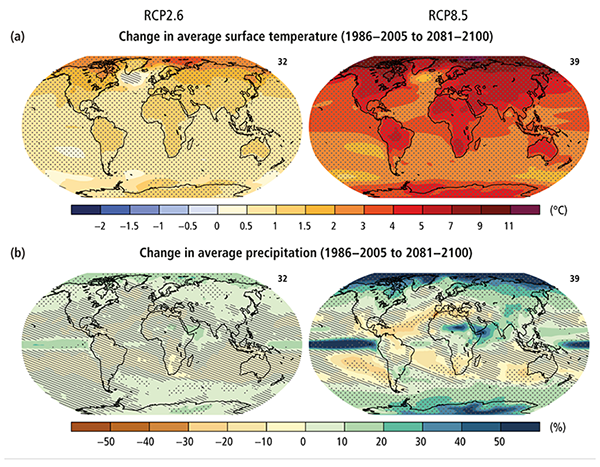

In addition, Reventazón makes Costa Rica even more dependent on hydropower for electricity. The country lies within a zone already suffering increasingly severe droughts. Climate models indicate higher temps and lower rainfall for the coming fifty years.

And then there’s the business of building new dams—which turns out to have an enormous carbon footprint. Dams are made with rock and concrete. The concrete industry is one of the two largest greenhouse gas emitting industries on the planet.3 In addition, when massive areas flood for the first time when a dam is erected, not only does the area lose the ability to take up carbon dioxide, the drowned trees emit methane, a greenhouse gas ten times more potent than carbon dioxide.4 This is particularly true in the tropics.

By contrast, while Costa Rica accrues foreign debt in a rush to build more massive dams, the US removes dams. Many of the removed dams in the US are small to medium size, and updating their energy-producing capacity isn’t worth the expensive bill. Beyond updates, the ‘developed’ world is valuing the natural functions of rivers more, while a ‘developing’ country pushes in the opposite direction. Solar, wind, and geothermal are at the forefront of renewable energy development, where smart grid management and storage can balance the intermittent input of sun and wind. But large buildup of this renewable generation seems strangely reserved for rich nations.

Dams are the low-tech, old-fashioned, high-capital way of the past, the expensive path of progress that has previously sunk entire nations. In the early 1980s, Latin American countries borrowed huge sums of money from international creditors to build industrialization projects, especially infrastructure. Costa Rica finds itself increasingly locked in to uneasy old debt patterns, an echo of the Latin American debt crisis.

Despite these issues, Costa Rica forges forward with their largest proposed dam yet, twice the size of Reventazón. It’s called the Diquís project, and protests have plagued it since the idea’s inception 20 years ago. The dam would flood the homes and land of the Térraba indigenous people and five other indigenous groups.

In 1956, the Costa Rican government granted the Térraba title to part of their traditional territory. However, the title was amended and reduced in 2004 without notice to the people. The Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE) then approved the Diquís dam, which would create a 27-square-mile lake that would flood ten percent of all of the Térraba’s land holdings. This includes farmland and over 300 sacred sites of archeological significance, displacing not only the tribe but their cultural heritage.

When dam construction began in 2007, the Térraba were again not consulted. However, with support from the United Nations, the community filed suit against ICE for indigenous and human rights violations, and the $2 billion project has remained (mostly) halted since. But Costa Rica feels the pressure to build the dam as an international energy market emerges for Central America, one where an interconnected grid means that countries could sell their excess power for a profit to other countries. The government wants to exploit the water that they have now—no matter the future of their water supply and their native people.

Yet not only would the dam displace native peoples, it would also alter one of the most productive watersheds and estuaries in all of Central America. The massive estuaries and mangrove swamps are an important breeding ground for the fish that support the entire ocean food system in Pacific Costa Rica. This brings us back to the conflicts of turtles, sharks, and desperate fishermen. It comes back to affect fishers in a vicious cycle, a sad perspective on the phrase, “we all live downstream.”

In 1994, Costa Rica amended their constitution to guarantee “every citizen the right to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment.” Two years later, the constitution was amended again to make clear that the “state is obligated to ensure that protection.” With giant, international-debt-incurring dams, the state does just the opposite. This not only hurts individual Costa Ricans, it erodes the state’s carefully constructed image as the ‘success story’ of Central America.

Ultimately, dams are at best a risky investment as rainfall becomes more unpredictable and more scarce. Costa Rica claims it already knows that the real money is in conserving natural systems. But their actions show that their reputation for ‘green’ energy is more important than the green ecosystems on which their tourism trade depends.

Reputations in a Changing World

Once I have spent a little time with a new acquaintance on my travels, I usually ask the same question before I tell them about my interest in climate change: what’s the biggest problem facing Costa Rica today?

I ask Wilson, our van driver, who has a thriving shuttle business and a ten year old son. He answers quickly, and I can hear the alarm in his voice.

“The narcos. They aren’t in my town so far, but I hear the stories. How they come in and take control and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

“We need a military to defend against this.”

The lack of a military in Costa Rica was the heart of national pride a generation ago. But that’s been slowly overtaken by the modern concerns of drug trafficking, which has even infiltrated the established fisheries and environmental conservation. At the center of the powerful Costa Rican pride now is ecotourism. But even that seems to be fading in favor of an international image as a leader in renewable energy.

No matter the cost.

* * *

Anchored in a cove near Quepos, we finally meet a local fisherman-turned-lounge-chair-deliverer. Marcos Manini speeds by our sailboat, throttling his panga through the cove and its uncharted rocks, to drop off and set up 20 plastic lounge chairs, colorful shade umbrellas, five paddleboards and three sit-on-top plastic kayaks that he tows behind his overloaded boat every day. He’s like the Clampetts on water. He’s imposing from afar with his big gut, bare feet, and curly mullet. We exchange friendly waves every morning until he finally swings by, curious. He’s laidback, and I like him immediately. I give him a cup of coffee and his eyes widen.

“Instantaneo?”

“No.” I grin and tell him it’s my favorite coffee from Chiapas, Mexico. He nods approvingly.

That afternoon, he returns with two fresh red snapper, ‘frescito’, the freshest. When I offer him money, he refuses. Snapper are high quality fish that can fetch decent money around here, so I’m touched by his generous gift.

Over the next month, Marcos stops by for coffee when he has time, and we invite him aboard once in a while. We relate our motor issues, and he inquires among his fishing friends about a new motor for us (which was an excellent price—but couldn’t work with a sailboat with a wet exhaust system.) We fix a fishing reel for him. I push his boat off the beach one day when his apprentice neglects it at low tide. Marcos has been shuttling chairs and kayaks for years, and it feels like we get to be his neighbor for a moment.

When we finally have to leave, we tell him we will be gone by the time he arrives in the morning, around 7am. There are many smiles and handshakes, and as he motors away, he turns around one last time and waves, his face lit with bright eyes and a caring grin.

Like Wilson and Oli, Marcos embodies what we have come to learn is a piece of authentic Costa Rica: friendly people. As the government clumsily navigates a changing world, this little country still manages to educate locals who take sincere pride in their pristine rainforests.

I think of the adaptability of the country, renowned for its peacefulness, rainforests, and beaches—all threatened, in one form or another, by the looming wave of climate change. Far removed from our rural anchorage and Marcos’ daily beach chair shuttle, Costa Rica’s Foreign Minister Manuel González warned countries in the developing world at the 2015 Paris climate talks: “Big or small, all of you are like Costa Rica: without an army to defend yourself against climate change.”

I step onto the rail and watch as Marcos disappears into the haze over the sea.

_____________________________________

ENDNOTES

1 This information comes purely from visual observation. On a sailboat, at least one person should always be looking around for boats, hazards, weather, etc. We saw the entire Pacific coast at around 5 knots speed over the last year, just a little bit fast than a jog.

2 The 1991 definition from The International Ecotourism Society (TIES)

3 Up to 5 percent of manmade emissions come from the industry: 50 percent from the chemical process and 40 percent from burning fuel for processing.

4 Methane disappears more quickly than carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, in tens of years instead of hundreds. However, their acute warming ability could spell quickened land and sea ice melting, a process with a high positive feedback loop (as more ice melts, the faster the remaining ice disappears.) If there is a ‘tipping point’ for warming, methane is a key ingredient to get us there.