War correspondent, author and former ICWA fellow Thomas Goltz (Turkey, Uzbekistan, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Iran, 1991 – 1993)—who described himself as “Mr. Bridge-Too-Far”—died July 29 in Livingston, Montana at the age of 68 after a long battle with cancer, his brother Neill E. Goltz said.

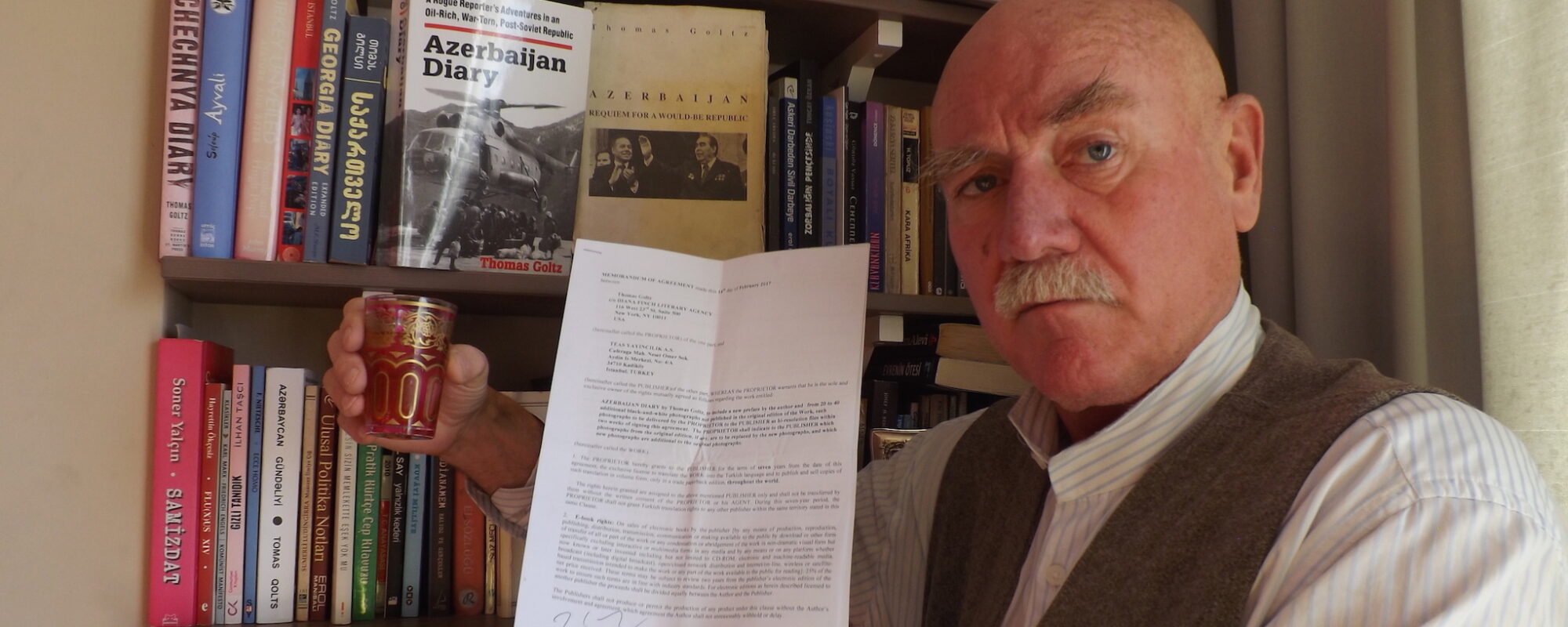

He was best known for his accounts of brutal conflict in the post-Soviet Caucasus region during the 1990s, especially his first book Azerbaijan Diary, based on his fellowship research, which recorded the mass killing of Azerbaijanis in 1992.

It “is far and away the best account of the era, a powerful, humorous, Thompsonesque portrait of the early 1990s,” the journalist Steve LeVine of Georgetown University tweeted.

A fixture at many ICWA meetings he would sometimes attend sporting a bow tie together with military fatigues and combat boots, and often court controversy, Thomas was rarely far from the center of attention.

“To some, he may have seemed over-bearing, a maverick or even a recklessly unguided missile,” wrote his friend Hugh Pope, a former reporter and International Crisis Group director of communications, “for many more, like me, Thomas will be deeply missed as a unique, funny and loyal friend and storyteller who made a virtue of never accepting any limits.”

“Sporting the bushy moustache of a 19th-century German general and topping his smoothly shaved head with a variety of Turkish and Caucasian caps,” he added, “Thomas was an inimitable, all-in reporter.”

His relationship with Azerbaijan, which began on his ICWA fellowship, started by chance, according to his own description. Recently graduated from New York University with a master’s degree in Middle East studies, he was on his way to Central Asia. When his plane stopped over in the Azeri capital Baku, he realized war between Azerbaijan and Armenia was breaking out.

“He called up ICWA and said I know my assignment is in Tajikistan, but this really seems to be where the actions is. Would you mind if I stayed here instead?” his brother Neill said. “That launched his career and made him who he was.”

Thomas’s life-long relationship with the country later included promoting an oil pipeline to Turkey by staging a motorcycle expedition along the route.

The authoritarian president, Ilham Aliyev, issued a condolence note. “I always remember with fond memories my meetings and conversations with him, and particular our meeting in Shusha in May of this year,” he wrote. “Bright memory of Thomas Goltz will always live in the hearts of the Azerbaijani people.”

While on his fellowship, Thomas traveled the entire Caucasus region, and volunteered to help with relief for the Kurdish refugee crisis in the aftermath of the first Gulf war. “I showed up in Iraqi Kurdistan and offered myself up to a group of international NGOs who needed a ‘logistician,’ meaning that they needed a guy to organize everything they could not do, or did not want to touch,” he recently wrote. He recruited his doctor father to serve as a physician there with Doctors Without Borders.

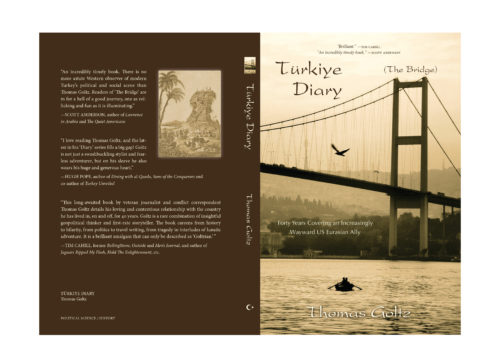

Thomas also wrote books about Armenia, Georgia, Chechnya and elsewhere. His other work included a documentary film about a brutalized village in Chechnya during the first Chechen war in the 1990s, for which he was a finalist for a 1996 Rory Peck award.

“Survival in those places called for clever tricks,” his friend the journalist Scott McMillion wrote, “bribing an Aeroflot pilot with a handful of Cuban cigars to get a free seat; leading a 60 Minutes crew to obscure petroleum baths in Azerbaijan; surviving in a Syrian prison by telling jokes in Arabic; supporting himself all across Africa with a one-man Shakespearean puppet show.”

“I… sallied forth with the pretense of changing the world,” Thomas told an interviewer in 2003. “This is common to many journalists, young and old, that that article that you write… will be so effective that the viewer, the reader, will stand up and shout: ‘Stop, stop this war! Stop this madness!’”

Thomas was married to Hicran Oje, a Turkish doctor based in Istanbul, where he lived for a time. He eventually established his base in Montana, where he sometimes taught university classes, also traveling widely. His parents sometimes accompanied him.

Late in his life, he wrote that he worried his mother Deborah with his “potential for engaging in unnecessary geopolitical foolishness, which (some might posit) is a signature of my career.”

Tributes have poured in. “He came to my rescue once in Chechnya,” the former BBC reporter Robert Parsons tweeted. “I was being aggressively questioned at a Chechen checkpoint when he appeared out of nowhere. Dr. Parsons, I presume, he said and calmed everyone down.”

Former ICWA fellow, trustee and fellow journalist Joel Millman said Thomas was “the most prolific and most enthusiastic of fellows, both during his fellowship when we first met and for nearly three decades afterward.

“He was a frequent house guest when passing through Manhattan,” he added. “I remember one New York visit that involved me watching Goltz barbeque venison he shot and cured in a New York City hotel room’s fireplace. Fellow guests included the UN delegation of the newly independent nation of Azerbaijan.”

His brother Neill said, “I’m not sure what line one crosses to qualify as ‘larger than life,’ but Tommy was certainly close to that threshold if not over it.”

Thomas was born in Japan, the second of eight children, to Neill F. Goltz, an ear nose and throat physician, and Deborah Donnelly Goltz, a classically trained pianist, and raised in North Dakota.

He spoke German, Spanish, Turkish, Azerbaijani, Russian, Arabic, Kurdish, Georgian and Farsi.

In 2020, he received an honorary doctorate from ADA University in Baku for his contributions to understanding between Azerbaijan, its neighbors and the United States.

Thomas is survived by his wife, mother and seven siblings: Neill, Edward, Martha, Julia, Stanislaus, Vincent and Charles.

A memorial will be held at 3 p.m. on Aug. 20 at the Shane Lalani Center for the Arts at 415 E. Lewis in Livingston, Montana. Please contact the institute for information about attending by Zoom.