“At night, it looked like another city,” Isabel tells me as she gestures out her office window toward the sea. “There were hundreds of lights. But now, what do you see?” she asks me.

“Nada,” I reply.

Isabel Soto Gonzalez runs the daily operations at the marina in Santa Rosalía. She tells me that the harbor (where we are docked to diagnose our faulty batteries) used to be full of calamareros, squid fishermen. This floating city of light just outside of the harbor puled in thousands of pounds of Humboldt squid every night. This mysterious six-foot-long predator is known for its massive size and an ability to rapidly change color from white to red. It has a beak so sharp it can cleanly shear a finger off a careless fisherman.

To catch squid, boats ply the nighttime waters with bright halogen bulbs directed on the water’s surface. This attracts plankton and little fish, which in turn lures the night-feeding squid. These days, panga fishing boats zip in and out of the inner harbor, or dársena, but mostly during daylight hours. The fishery for the giant squid supported hundreds of boats and over a thousand people—until the squid disappeared in the winter of 2009 and never returned.

“Too many fishermen?” I ask. Hundreds of boats in one area sounds like too much pressure on one species.

“I’m not sure. The squid supported all those boats for years. Then they just disappeared so fast.”

The first time I heard about the rapid disappearance of an ocean species it was the black abalone. The warm water from the powerful 1997 El Niño caused the abalone to succumb to a naturally occurring disease, causing a catastrophic population crash. Yet no one speaks of a 2009 El Niño, and the El Niño events between the powerful 1997 and 2015 occurrences were significantly more mild.

Almost 10 percent of the 12,000 residents of Santa Rosalía earned their income through the capture, processing, and sale of squid. As I talk with people in town, it’s clear that the disappearance of the Humboldt still reverberates in the community. An entire industry was lost in one season—and at first no one here can tell me why.

A Harbor First For Land, Then For Sea

The story begins not on the sea, but the land. In 1868, a rancher discovered copper in Santa Rosalía in the form of blue-green concretions, or boleos. He supposedly sold his claim for a measly 16 pesos, and in 1884 a French company gobbled up claims, followed by a 200-kilometer grant from the Mexican government in 1885. Compagnie Boleo (El Boleo Copper Company) developed 375 miles of tunnels under the pueblo and Santa Rosalía joined many other Mexican towns in an era of resource exploitation that filled foreign pockets. Massive maroon piles of tierra quemada, or scorched earth, still preside in perfect cones on the town’s north mesa. When production waned and the Mexican Revolution started the process of taking back Mexico’s resources, the French sold the mine but left their distinct architectural stamp. Instead of the typical coastal structures of concrete and thatch roofs, there are rows of charming wooden clapboard buildings and corrugated red tin roofs. A steel frame church, designed by Alexander Gustave Eiffel of the famed Paris landmark, was disassembled in Belgium and shipped around the South America’s Cape Horn in 1897 to Santa Rosalía, where its bell still tolls today.

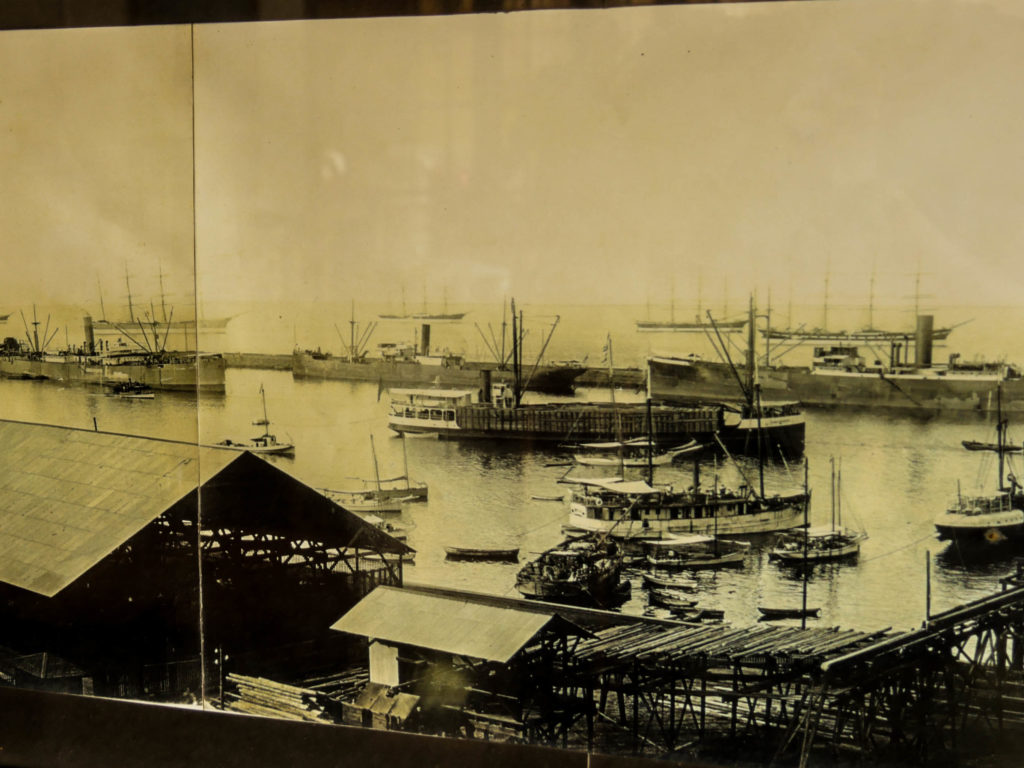

The French also left a crucial piece of infrastructure. This one relic of the mine now supports the size and economic bustle of the town: the harbor.

I learn this from Elías Moreno Camacho, the maintenance man at the marina. Elías is 54 years old and was born in Santa Rosalía. When he talks about how the quiet but towering nearby volcanoes drop straight into the water, his blue eyes get a little glassy and the crinkles around them soften.

Because of the mining operations, Santa Rosalía has the unique advantage of having the only breakwater and inner harbor for hundreds of miles. Indeed, this is the only reason that we are able to safely stay here on our sailboat—it would otherwise be an open and exposed strip of coast. The mining operation used the first slag from the mine to build the harbor’s rock wall. The ripples of obsidian-like, smooth black rock hold a stodgy edge against the sea. Originally, the harbor was built to import materials, such as massive wooden beams unavailable in the Baja desert landscape, and export the copper. Today, the harbor is used by a ferry from the mainland and the fishermen in their sturdy pangas, the 25-foot outboard-powered boats with a high bow and shallow draft.

Elías extolls the other virtue of the breakwater: it not only protects boats, but the town arroyo, or the valley between two mesas that funnels all water from surrounding mountains to the sea. The storm surge from the sea can inundate arroyos and the towns surrounding them. Storm surge occurs when the ferocious wind and waves of a hurricane cause the ocean to rise much higher than normal, stacking up at the land and flooding coastal areas.

Like almost all of the towns in Baja, Santa Rosalía is built in an arroyo. Mulegé, a town 30 miles south, is regularly ravaged by the ocean floods during hurricanes. But that doesn’t happen here, Elías tells me, because the mine created this sturdy breakwater. The mine may have brought many negatives, but it uniquely protected Santa Rosalía from one of the most dangerous impacts sea level rise and climate change. Mulegé needs a mine, he jokes. But he has pointed out that the extractive industry on the land protected a town—and thousands of fishing boats—that would otherwise not exist.

Perhaps this harbor, which shelters the town and the boats from increasingly dangerous hurricanes, explains the squid disappearance. The dársena was able to house hundreds of boats as squid became an increasing sought-after—and expensive—source of food. Long popular in the Mediterranean and Japan, the squid market is growing in popularity thanks in part to decreasing fish stocks. Because the Humboldt squid are so large and the harbor so protected, it makes good economic sense to catch hundreds of pounds in one night and have a safe harbor nearby to easily offload their fresh catch every morning. So did the calamareros take too many too fast?

The Shrinking of the Squid

In fact, the squid aren’t all gone, a fisherman tells me. They’re still here—just smaller. This could mean that the large adults were fished out. However, with the short lifespan of the calamar, the stock should have recovered after a couple of years.

Isabel, now my ally in solving this mystery, sends me down the street from the marina to a small, squat building pinned between a restaurant and a convenience store on the edge of a black sand beach.

Martín Gozalez Rivas has overseen the fishing community here for 15 years. He is the Director of the federal Secretary of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries, and Food, SAGARPA, in Santa Rosalía. Or, as Martín says, he’s the jefe de pesca, the fishery boss. Martin’s manner is brisk and tidy, like his cleanly pressed light blue shirt. He was born in a tiny desert town in the center of the Baja peninsula, Vizcaíno, and he didn’t see the ocean until he was 18 years old.

“But once I saw it, that was it,” he states with an emphatic hand chop. “I knew that’s what I would do for the rest of my life.” He studied Oceanography in college in Ensenada, and has worked on the coasts of Baja for the past 26 years. Martín is the person who finally clues me in to the cause of the fishery collapse: warm water.

“In 2009, the currents changed, heating up the sea.” He knows this because he saw a change in the fishers’ catch, and not only in squid. It was a good year for lobster but a bad year for most fish.

In 2009, there was a mild El Niño, and this brought a surge of warm water into the Sea of Cortez. El Niños start a thousand miles away, at the equator, when the wind blows backwards. Normally, it blows east to west, from Peru toward Samoa. During El Niño years, low pressure builds up over the equator, and high pressure from the South Pacific rushes in to equalize the pressure. This global balance of weather pressure manifests as wind. The wind pushes water warmed on the surface of the South Pacific towards South America. The warm water flows east, then eventually to the north.

It’s a natural cycle, but a warmer globe means more frequent changes in weather patterns that cause El Niños. In addition, a warmer atmosphere and ocean mean El Niños can have warmer water, occur more frequently and with more effects, and cause difficult-to-predict regional and local changes to currents and weather. Warm water in the Sea of Cortez was one of the subtle regional changes in 2009.

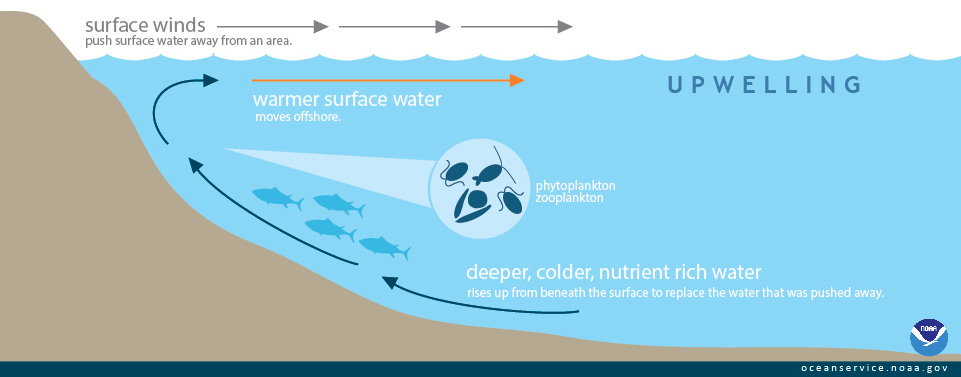

This warm water affects the underwater food conveyor belt. The Sea of Cortez typically experiences ‘upwelling’ in the water at the coast. Coastal winds blow the surface water away from the shore, and that allows the colder, nutrient-rich water from deeper in the sea to takes its place. This upwelling brings marine invertebrates to the surface near the coasts, feeding everything from little cochito (trigger fish) to Blue whales, the largest creature to ever exist on earth. This is one of the reasons for the Sea’s remarkable biodiversity, prompting Jacques Cousteau to call the Sea of Cortez “the world’s aquarium.”

During El Niño years, warm water flows into the Sea from the equator, trapping the cold water 150 feet below the surface. The upwelling current can´t cycle nutrients to the coastal water, so all of the animals that typically feast near the shore must look elsewhere for food.

The Humboldt squid, however, did something far more bizarre than just move. During a 2010 research cruise in the Sea of Cortez, Stanford biologist William Gilly discovered that the squid were sexually mature and spawning when they were only 6-months-old and a pound apiece, as opposed to their typical spawning at 18 months and 20 to 30 pounds.

“It was obvious that the squid were pretty screwed up,” Gilly said.

Eventually, he and his students found giant squid that had migrated to the Midriff Islands, 100 miles north of Santa Rosalía. At this spot, the land squeezes the sea to its narrowest point, and tidal currents are strong enough to remain unaffected by the influx of warm surface water. Once the squid moved to this area, they could still feast on reliable food until they were 30 pounds and a year-and-a-half old.

However, the few squid that stayed near Santa Rosalía bred a full year younger and only a fraction of their possible full size. Most creatures do not have this option to breed smaller, and it’s a unique adaptation of the squid given limited food. If they had needed to grow for another year, that population would have died out. Instead, they shrunk.

Seven years later, the giant squid still haven’t returned in numbers to support the ‘floating city’ outside the Santa Rosalía harbor. With a lifespan of six to eighteen months, squid don’t have much time for a memory of old breeding and feeding grounds. There are still squid at the shore, as noted by the fishermen, but nothing in number or size like before.

The Fallout on Land—and Sea

The fishermen couldn’t live off these tiny versions of the Humboldt squid—they don’t sell for nearly as much as a big calamari steak. Nor could the fishermen migrate over 100 miles in their open pangas to the ripping tidal currents around the Midriff Islands. Hundreds of boats of fishermen were suddenly out of work.

“There were many robberies. People were desperate,” Isabel tells me. “But who can blame them?” Their entire livelihood disappeared in one winter. Many of the transient calamareros left—but some, especially those who grew up here, wanted to stay.

What did the community do to confront this change? I ask Martín at SAGARPA.

“Well, they have adapted,” he says. This is the first time I’ve heard the word adaptation used.

“Ahh, you see, the calamareros are now pescaderos or tiburoneros (shark fishers),” Martín says wryly. “It works for now. But it means that the rest of the sea comes under more pressure, and they risk losing all of their livelihoods again if they can’t control their catch.”

One of the most common and effective ways for small-scale fisheries to govern their catch is a cooperative. A cooperative is an organization that self-governs their catch while creating collective bargaining power for their product. However, Martín tells me that the cooperatives in Santa Rosalía don’t function as they should. I make a note to talk with the fishermen about this.

Not only the men were affected by the loss of the squid—women and families felt the change as well. When I talk with Yerenia Aguilar Mesa, at FONMAR, the state-level agency that supports marine-based work, I ask her about how changes in the fisheries affect women.

“There were a lot of women who worked at the cannery,” she pauses, “—a lot of women. They all lost their jobs.” She notes that the fishermen have families to support. In some cases, both the husband and the wife were employed in different sides of the same industry. When that industry tanked, the family lost both incomes.

All of this because of warm water.

Riding the Current

In Mexico, there is a distinct pride in calling oneself a fisherman. Regardless of current work or situation, men state with dignity that they are a pescadero. It’s more than a job—it’s as much a part of them as the blood in their veins. Fishing is inseparable from their sense of self.

This continues to be the case with the soft-spoken fisherman I find working at the fueling station at the edge of the dársena. Vidál works the evening shift, from 5pm to 1am, and he and I sit on the curb in front of the gas station office under the yellow glow of the overhead lights, facing the sea. When I ask him que se dedica, what is your profession, he answers pescadero. Sure, he’s a gasolinero right now, but that’s only his job. He’s a fisherman as much as he’s a human.

Vidál was a fisherman by car. He used to drive the coast in search of octopus, and he would spearfish in rocky outcroppings along the coast. This kind of fishing is a very specific skill—to find and spear octopus. Octopus are intelligent as well as great at hiding. Despite spending a lot of time in the water, I have only seen two octopuses in the wild in my life. In addition, Vidál used a Hawaiana, a type of pole spear that uses a long elastic band inside a narrow pole to tension and shoot a three-point prong. This requires the ability to get within five feet of the target and be lightning fast and precise—all while holding one’s breath for minutes to find creatures designed to disappear under rocks. This makes his specialty a highly skilled profession requiring deep local knowledge. It’s also a skill threatened by the more destructive, larger scale fishers who rake the rocks with nets.

Unfortunately, Vidál can’t spearfish anymore because he lost his car in the hurricane last year. I asked him if he was supported by the fishing cooperatives.

He smiles grimly and shakes his head. “No. Son mafiados.”

It’s a mafia, he says. He tells me the cooperatives hold all of the permits for fishing. If an independent fisher, like he is, wants to get a permit to fish, he can’t do it without being a part of the co-op. But independent pescaderos can’t get into the co-op either. Instead of functioning to protect both the fish and the fishers, it functions as an exclusive club.

It’s not like this everywhere. On the Pacific coast, less than 100 miles to the west, cooperatives carry on their crucial functions: they police themselves, they carefully monitor and fish their product so it remains as consistent as possible, and they use their quality catch and solidarity to create market power. Yerenia at FONMAR grew up in La Bocana, a small Pacific fishing village, where all of the men are fishermen. She suspects that those co-ops function better because they have one cooperative per species, which is in part a function of a different permitting system. This helps pescaderos focus on the health and quality of catch of that species. The two sides of the peninsula have thus developed two very different styles of cooperatives.

Unwilling to deal with the politics of the cooperatives, Vidál found the job at the gas station when he couldn’t fish anymore. Does he like the job? I expect to hear no. Instead, he replies that he does.

I am terrible at disguising my reactions, so I must look surprised. Vidál smiles and shrugs.

“It’s steady work, and I get to be right next to the water.” He sweeps his hand out to the black sea just beyond the giant, above ground tank of diesel fuel.

Humans are remarkably tolerant of physical change. We have a high threshold for temperature shifts. As land-based bipeds who are soothed and restored by the sea, we rejoice and flock to the shore when the water is a little warmer. People, like Vidál, can change their work and shift their mindsets to survive in changing conditions.

However, we depend, for work and food, upon creatures which are sensitive to the slightest change in water temperature—even a couple of degrees. As a result, we are more vulnerable to temperature change than we might otherwise acknowledge. Santa Rosalía had proven at least partially resilient, even with its deeply flawed cooperative system. People live in Santa Rosalía because they like the small town, the seafood, and their roots. They want to be near the sea. Sometimes that may mean that their work isn’t on the water, but adaptability in this case comes from willingness to be flexible in work—and to wait and see if things improve.

****

Josh and I end up staying in Santa Rosalía for over a week to fix our boat’s electrical issues. Functioning batteries are crucial on the boat because we not only use them to start the motor, they run everything electronic, from our navigation system to our fans. We enlist an electrician and ultimately end up with three new batteries. As I talk with José, the electrician, he tells me he dreams of owning a sailboat. Since I have yet to meet a Mexican on a sailboat, I enthusiastically encourage him to find a boat—he already has all the skills to work on them. I write down two websites for him, and I can see a hint of hopefulness in his expression as he looks down at the paper between his thick fingers.

José moved from La Paz to Santa Rosalía only four years ago. The first time that he drove through Santa Rosalía, he returned to La Paz, sold his house, and moved everything to this pueblo eight hours to the north. I ask him why.

“I have no idea.” He laughs. “I like the small town, the seafood, and the ocean.” He affirms for me what I have already noticed about the people who choose to live in Santa Rosalía: they are willing to compromise to hang onto the life that they love, a life that they are consciously and actively choosing.

With new batteries, we leave the dock at three in the morning to motor into the blackness of night (to arrive at our next anchorage before dark.) We steer far away from shore to avoid the debris in the water from recent rains, and Josh and I alternate on bow watch with the spotlight to search for potential boat-damaging items. Daybreak finds us over five miles from shore. As the first sunlight pours from behind the clouds, a panga appears on the glassy horizon to our east. It barrels straight toward us, and only slows as they pull alongside. On the open sea, I’m concerned that the two men approached us because they have a problem. Everything okay? Sí.

Their panga overflows with mint green nets. With a big grin, the man in the middle reaches into the bottom of the boat and pulls up a four-foot Bonnethead shark, arching his back to lift it to his chest to show us. Both Josh and I exclaim, and I ask if we can take a photo.

Once my camera is out, the man at the motor, who seems to be the more experienced fisher, switches places with the young skinny man at the center, and as we two boats float together in miles of calm water, he lifts another shark, perhaps a Dusky, from the floor. He wraps his arms in a tight hug around the six-foot shark to thrust it over his head, like a snub-nosed trophy. I would normally feel sad about a dead shark, but their pride is palpable, and Josh and I cheer for these two men. They chased us down in the middle of the sea just so they could show us their catch.

In the hunt on the sea, a fisher must know the subtleties of two complex worlds: above the waterline, and below it. He must have the ability to navigate and fix a boat, and the savvy to find and trap a creature he can’t see until he pulls it from the water. It’s exciting to share a moment of their spoils. Their smiles glow with accomplishment.

We have sails up, so we are pulling away from their panga. With proud grins, the tiburoneros gun their outboard and disappear with their sharks into the open, wild, warming sea.