In a recent Newsletter (JVC-3), I shared the perspectives of Acehnese Muslims in an attempt to complicate singular notions of Islam. The Story of the Stick tuned in to the (dis)harmonies of Islamic belief and practice, and set the stage for a consideration of the role that religiosity and gender play in Banda Aceh’s political theater (JVC-4). [1]

One astute reader, a friend who has also spent significant time in Indonesia and Aceh, wrote to remind me to “emphasize just how different Islam is practiced [in Aceh] from other parts of Indonesia.” She also pointed out that “there is no uniformity in religion for the entire geography of Indonesia.” Her critique pushed me to reflect on how I had inadvertently reactivated the same media framing of Indonesia as a religious place that I had criticized in my opening paragraphs.

She’s right to note that Aceh is different – exceptional, even. Indonesians from elsewhere often define themselves against what they see as extremism in the province, presenting it as an exception to the rule of tolerance in the rest of the archipelago. Initial responses to any mention of my work there are almost always condemnations of the rules of syariah, often by Muslims who have never visited. I have taken to playfully dismantling this straw man (straw place?) fallacy, noting that depicting all Acehnese as religious fundamentalists fits incongruously with the other stereotype of the Acehnese as heavy consumers of coffee and cannabis.[2]

Only two months after the argument about a stick in Masjid Baiturrahman, police found and destroyed nine hectares of marijuana less than an hour’s drive from that sacred place.[3] That’s a newsworthy amount of ganja, but no international media outlet covered it. Why is it so difficult to view Indonesia outside of the prism of religion? I’m complicit here – I introduced you to Aceh by repeatedly referencing its grand masjid, which had an effect altogether different than had I ushered you into this rich culture with a cup of “coffee buffoonery.”2 How do our impressions of this syariah law-observant place change upon acknowledging that all this coexists?

The duality proves my friend’s point: it is problematic to think about beliefs and practices in terms of geography, even at the city level. Subcultures and deviants in all corners of Indonesia tend not to own spaces or dominate discourses, but they give the lie to normative ideologies, religious or otherwise. All too often, they escape reportage, and this matters: the act of looking creates the seen, but also the unseen. And seeing is an act of privilege and power.

In this Newsletter, I argue that the insistence on viewing Indonesia primarily as a religious place has actually marginalized moderatism and silenced secular voices. By detailing an event hosted recently by the Sacred Bridge Foundation,[4] a collective of freethinkers and misfits bound together less by geography and place than by ideals and space, I engage you in a consideration of how place and space structure religiosity, radicalism, and revolution.

Place and Space

Since the publication of Henri Lefebvre’s “La production de l’espace” in 1974, social theorists have increasingly differentiated between space, or a location where events occur, and place, which is a social construction that results from our assignment of value to any particular space. In other words, space + meaning = place.

Place is a product of human imagination, and can involve geography, material objects, social institutions, the built environment, imaginary sites, and ideological positions.[5] The difference between space and place lies in the difference between, for example, a city and New York City, with its World Trade Center, Apollo Theater, and Wall Street Bull (and now, fearless girl!). All of these component parts would qualify as places as well.

This distinction between space and place may seem merely academic, but consider the way that space, when socially organized, becomes place: Christians congregate in a building to pray, and the resultant cathedral creates place – it allows for the dissemination of beliefs and the transmission of social and financial capital.

Just as we embed meaning in spaces to organize the world around us, we perceive meaning in the disorganization of space: the toppling of 154 headstones in a cemetery [6] in my hometown of St. Louis, Missouri caused feelings of victimization and fear even for people who had never been there, or who are not Jewish.

Spatial theory has proven useful in religious studies, where spaces have been divided into the sacred and the profane and places have been defined as being created through ritual. This division serves well to differentiate between the masjids and coffeeshops of Aceh: though many people frequent both, their rituals in these spaces differ. And despite the fact that cannabis consumption has a sacral history tracing its lineage back to India, these days most would deem coffeeshops making marijuana mixtures to be profane. This profanity spills into our willingness to see: the likelihood of censure and counsel would likely have been much higher had I written an entire Newsletter about Aceh’s ganja guzzlers.

Normative thinking cements itself in place, and religious edifices are testaments of adherence to doctrine. As such, establishing place is also an act of power and privilege, just as is seeing. In Indonesia, learning about the lived experience of the disempowered is hindered by the ban on atheists creating place. Even irreligious space is condemned: Alexander Aan spent nineteen months in jail for proclaiming his (dis)belief on the “Indonesian Atheists” facebook group wall.[7]

Atheists aren’t the only non-dominant group denied place in Indonesia. A Protestant group just east of Jakarta has been trying to construct a church since 2008, but local Muslim authorities have unjustly denied them the requisite permits. A 2010 court ruling ordered local leaders to accede to HKBP Filadelfia’s request, but the ruling was abrogated without consequence. In 2012, when the group tried to establish place by conducting Christmas devotional activities in the empty space where their church should be, they were assailed with rotten eggs, urine, and frogs.[8] Their assailants were not apprehended or charged.

Denying place preserves power; destroying place consolidates it. Just as in St. Louis, Jewish places in Indonesia have been desecrated in an attempt to erase history. The Beith Shalom synagogue, which the Dutch constructed in Surabaya in 1939 and which local residents had recommended for heritage status, was demolished by “unidentified persons” in 2013.[9] No investigation was conducted. The Jewish community cannot push the issue, as theirs is not a recognized religion.

But state recognition does not safeguard place for minority groups either. The Al Kautsar masjid in Kendal, Central Java was vandalized in 2004, 2006, and 2011; last May, its roof and walls were torn down.[10] My use of passive voice denotes the refusal on the part of local authorities to assign culpability. Why did the wardens of power turn a cold shoulder on their fellow Muslims? Because they are Ahmadi.[11]

Assaults against Ahmadi places have been on the uptick since the issuance of a decree in 2008 requiring Ahmadiyah to “stop spreading interpretations and activities that deviate from the principle teachings of Islam” [my emphasis denotes the normatization of Sunni ideology in Indonesia]. The most notable conflagration occurred in 2011, when cars and a masjid were burned and three young boys brutally murdered in Cikeusik, West Java. Video of these attacks posted online garnered international attention.[12] A chilling legal precedent was set for Indonesian minority groups when an Ahmadi man received a longer sentence than the ten men and two boys charged with attacking his community.[13]

* * *

The examples above demonstrate that the denial and destruction of place decreases diversity and undermines equality. Such incidents erode interpersonal trust and increase feelings of fear, especially for members of minority groups. Opportunities for intergroup harmony dwindle as we seek refuge among people who share aspects of our identity. This is a global phenomenon. Humanity is increasingly dividing along lines of race, class, nationality, gender, ability and more.

Robert Putnam documented this trend toward social atomization in his book, “Bowling Alone.” He argued that as Americans stopped attending their bowling leagues and Optimist International meetings, they forfeited “bridging” social capital, the kind that helps us connect despite our differences.

I contend that Indonesia is experiencing the inverse of this. The standardization of religious practice has helped congregants amass “bonding” social capital, the kind we form with people who share our beliefs and ideals. This trend toward dividing social capital along religious lines might best be referred to as “Praying Apart.”[14] As syncretic strains of faith have diminished, the chances to engage in interfaith dialogue have decreased and the opportunities to form bridging social capital have become fewer and farther between.

Fear and mistrust lead people to seclude themselves in spaces populated by like minds. As we retreat into our respective corners; Others seem extreme, and even the middle appears marginal. The hallowed ground we once shared gives way as more people vacate it. To turn this around – to reenter diverse spaces, to reestablish places that encourage differences of thinking and being, to recommit ourselves to mutual respect and equality – will require the amassment of quite a bit of bridging social capital. I found a space in Indonesia where this is happening. Appropriately enough, the space is called “the Sacred Bridge.”

“A revolution that does not create a new space has not realized its full potential.”

~Henri Lefebvre

Crossing Over

In a place where everyone is expected to adhere to one of six recognized religions, promoting equality and diversity is nothing less than an act of revolution. Connecting across lines of tribe and faith in Indonesia happens all the time, but it happens less and less as time passes.[15] The democratic implications are considerable.

Enter the Sacred Bridge Foundation (SBF). Proclaiming itself to be “dedicated to culture,” defined as “the human context in all aspects of life,” and to “bringing about an era of ethics,” the group brings people of all walks of life (back) together to produce paintings, make music, and discuss difference. SBF approaches these goals via Vox de Cultura,[16] the inter-local radio station that bridges musical traditions to bring localities to global audiences, and Listen to the World (LttW),[17] a website that uses issues surrounding music to tackle cultural matters.

Last month, the group took on the topic of radicalization. LttW’s managing editor, Garry Poluan, had invited me to share my perspective, but I had misgivings: as an outsider, my presence often changes spaces. And since the discussion was to be held in Bahasa Indonesia, I felt more inclined to listen than to share. I wasn’t sure how much I would hear though- open discussions of religious fundamentalism often don’t dig deep, and names aren’t named among conflict-averse Indonesians.

Garry assuaged my concerns and challenged an assumption I’d inadvertently made – the same one that had structured my Newsletter: “It’s not limited to the realm of religion…Radicalization for me is that process of forcing others to believe in that same extreme mindset one has. Whether one is a radical surrealist, anarchist, or race supremacist, s/he can take part in radicalization. A hardcore Surrealist, for instance, who believes that surrealism is the best form of art…is no less radical [than] someone who thinks s/he has the right to force his/her religious belief on others because s/he considers that religion as the only way to ‘succeed’ in life.”

My curiosity sufficiently piqued, I headed over one balmy afternoon to a South Jakarta park. Green space is lacking in this city renowned for its traffic jams, so I was pleasantly surprised when I arrived to find verdant shrubs and a bubbling stream that was relatively clean. It seemed somehow fitting that the pavilion where the event was to be held, the largest of many dotting the park, is called the “Park Cultivation Building.” As we cultivated meaning here, we changed space into place.

After some time spent socializing, guests and panelists took seats on the floor of the simply decorated space. In the back of the room lay a large canvas which we would soon be invited to paint on – whatever we wanted, whenever we wished. At the front of the room stood a screen and Garry, who commenced the meeting by introducing the topic and explaining that “radicalization” did not mean terrorism, but rather the extreme mindsets or viewpoints in any subject area that don’t seek to move to the center. After introducing the panelists, our host invited us to speak up at leisure, noting that this was to be a discussion, not a presentation.

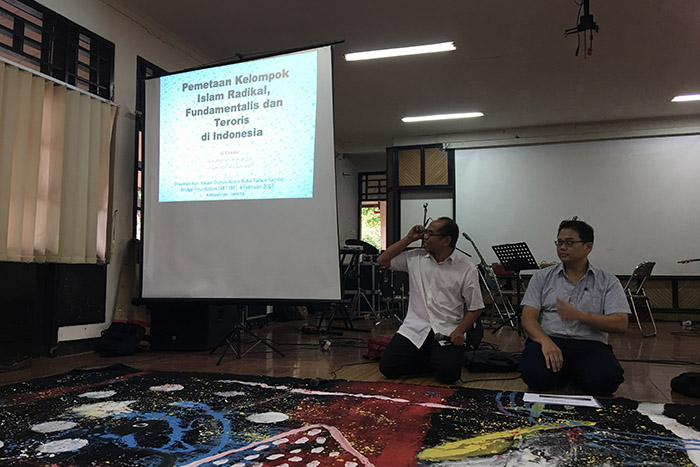

I was not entirely surprised when the first speaker, a professor from Lhoksemauwe, East Aceh, started off the “discussion” by framing it squarely on Islamic terrorism. Al Chaidar had been granted the first slot upon declaring that he would be giving a powerpoint presentation, which should have been the first sign things were about to go awry. His presentation, which took over an hour, was titled “Mapping Radical, Fundamentalist, and Terrorist Muslim Groups in Indonesia.”

When I spoke with Garry after the event, he confided that he felt it was unfortunate that “the discussion got pushed in the direction of radicalism in religion. I had intended it to be more holistic.” From my perspective, though, the professor’s presentation was enlightening: he identified nine specific fundamentalist groups and five radical groups by name, then explained how their increasing integration (their sharing of bonding social capital, as I would put it) has put terrorism on the map in Indonesia. He literally mapped terrorist activity, pointing to specific incidents in the Malukus, Aceh, and elsewhere. Finally, he addressed the influx of Wahhabism and Salafism (a topic I intend to detail in my next Newsletter). In pinning down particular groups, Al Chaidar’s presentation was itself radical.

When I mentioned this to Baiquni, my friend in Aceh, I learned why no one had objected to Al Chaidar hijacking the “discussion” to present his latest findings on religious radicalization: his very presence added meaning to the space, as the professor has gone into hiding several times in the past after receiving death threats related to his publications. Bai recounted that as a child, he would hide Al Chaidar’s book [18] about the Aceh Freedom Movement whenever Indonesian troops came through his neighborhood. It included pictures of soldiers holding severed heads.

Garry gracefully transitioned from the presentation to the discussion he had originally intended. In the second hour, a University of Indonesia professor shared information about cognitive openings and positive psychology, a representative of the Asia Foundation advocated for global ethics and active tolerance, and a cultural geographer spoke specifically of the Parmalim, an ethnic group which pre-exists Indonesia and does not practice any of its recognized religions. The audience joined in, and toward the end, I asked about the role education plays in utilizing cognitive openings to foster active tolerance and inculcate a global ethics, and how that was going in Indonesia. Not well, [19] the panelists and participants agreed.

* * *

After a short break for maghrib and mingling, food was served and beer and liquor were sold. I would learn later that posters for some of SBF’s first meetings would assure guests that the food would be halal, and that the beer would be cold.

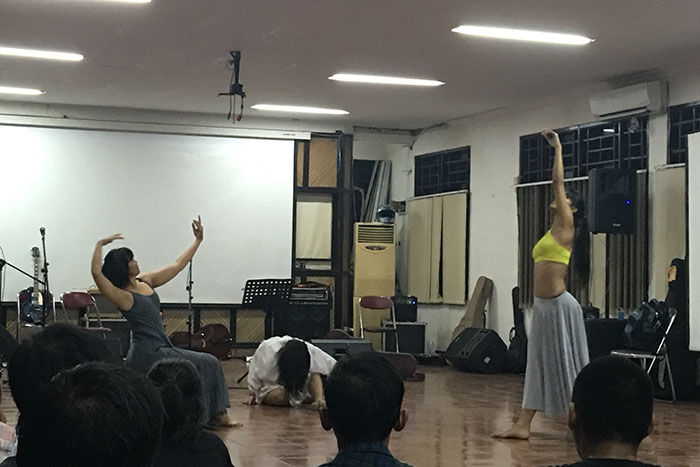

After dinner, the space was opened up to an exhibition of various arts. The choreography of the troupe that performed first danced upon the idea that a diverse three can unite as one. Garry’s stand-up comedy routine flirted with absurdity in witty ways, and the magician who followed added in some radical ribbing for some last laughs. And then we came to the paintings adorning the walls of the hall.

Bringing the night’s formal festivities to an end, an artist who had earlier introduced himself as a “radical kafir” [a loaded word meaning “unbeliever”] shared a meaningful message. With his fellow artists standing beside their paintings, Adikara Badama identified the graphic designer’s as “illustrative,” the interior decorator’s as “expressive,” and so on and so forth. He then came to the mess on the floor – a hodgepodge of scribbles, drops, dots and lines without apparent intent.

Capturing the theme of the evening and the movement, Adi explained that the piece on the floor is us, together. We are more comfortable viewing the works in isolation, assigned to genres. The neatness appeals, and it applies as well to how we would like to see society, divided into constituencies and framed with names. But the collaboration on the floor is all of the wall art, and more. It incorporates all our creativity by relinquishing control. We view the results as a mess, and struggle to recognize that mess as real, complete, and beautiful. But it is important that we try.

The night wound down to tunes of a group of musicians this event brought together. They decided to call the band “Ibumi” – a portmanteau of Ibu and Bumi. “Mother Earth” – a place we share, a mess we must learn to find beauty in again.

Listen to the World

SBF was formed nearly twenty years ago when a motley crew of businesspeople, professors, artists, activists, and others who elude classification was amalgamated as a pro bono project by a man who humbly ducks limelights, shares credit, and eschews recognition. The second time I meet him, he says that SBF is an attempt to bring together great minds, then immediately qualifies that by adding that Ph.D.s intimidate. To him, the greatest minds are those most passionate for change.

“And change can only happen on the ground,” he tells me. Underscoring the importance of establishing place in creating change, the founding member of the Sacred Bridge Foundation asserts that “if you’re only on the web, you’re not going to win. You have to be on the ground, doing real things.”

The websites of Vox de Cultura and Listen to the World receive over a thousand hits a month, mostly from America (both sites publish in English [20]), and my humble thought partner proudly states that “Listen to the World has a voice.” But he stresses a point that could just as well have come right from the Institute of Current World Affairs’ handbook: perspective-changing publication results from transformative fieldwork, because it is in the field that we learn to see.

“The way we look at things is important. A single perspective can be dangerous. The more perspectives we encounter, the more we know, and the more proportional our decisions will be.”

For all my studies, it seems I am just beginning to see…

“And you’re shinin’

like the brightest star

A transmission

on the midnight

radio,

And you’re spinnin’

like a forty-five

Ballerina

dancing to your rock and roll”

~Hedwig and the Angry Inch

[1] Illiza ended up losing the mayoral race in a landslide. Her opponent, Aminullah Usman, nearly doubled her vote total, 18,232 to 9,401. http://mediaindonesia.com/news/read/92346/calon-wali-kota-petahana-banda-aceh-kalah-telak/2017-02-15

[2] http://www.smh.com.au/world/coffee-and-ganja-provide-a-healthy-income-in-aceh-20150111-12ltev.html

[3] http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/08/29/aceh-police-destroy-9-hectares-of-marijuana.html

[4] http://www.sacredbridge.org/

[5] https://sites.utexas.edu/religion-theory/bibliographical-resources/spatial-theory/overview/

[6] http://www.npr.org/2017/02/21/516488403/headstones-vandalized-at-jewish-cemetery-in-missouri

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/04/world/asia/indonesian-who-embraced-atheism-landed-in-prison.html?_r=0

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/may/03/indonesia-atheists-religious-freedom-aan

[8] http://www.voaindonesia.com/a/jemaat-gereja-hkbp-bekasi-diserang-massa-saat-akan-gelar-kebaktian-natal/1571170.html

[9] http://www.timesofisrael.com/indonesias-last-synagogue-an-intended-heritage-site-destroyed/

[10] http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/05/23/ahmadiyah-mosque-in-c-java-attacked.html

[11] Ahmadi Muslims are considered apostates by most Sunni Muslims because Ahmadis believe the messiah returned to Earth in 1889. Though 90% of Indonesians are Sunni, the nation has not strictly banned Ahmadi practices. This uncomfortable tension over the meaning of “messiah” among Muslims has resulted in a spree of assaults against Ahmadis throughout the archipelago.

[12] Trigger warning: this video depicts graphic violence; viewing it is not for the faint of heart. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfr5pyIIMBM

[13] https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/07/28/indonesia-verdicts-setback-religious-freedom

[14] The prohibition on non-Muslims entering masjids further delimits the space available for interfaith dialogue, which is a significant limiting factor in a country that is 87% Muslim.

[15] http://www.smh.com.au/world/pluralism-in-peril-is-indonesias-religious-tolerance-under-threat-20161222-gth09i.html

[16] http://www.voxdecultura.net/

[17] http://www.listentotheworld.net/

[18] https://www.bukalapak.com/p/hobi-koleksi/buku/sejarah/3p8ld7-jual-gerakan-aceh-merdeka-al-chaidar

[19] http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/02/06/teachers-struggle-to-promote-tolerance.html

http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/02/10/indonesia-aims-to-root-out-bigotry-in-schools-mosques.html

[20] Sacred Bridge Foundation events are facilitated in Bahasa Indonesia. All quotes in this Newsletter are my translations.