On February 6, the ancient city of Antakya, the capital of Turkey’s southern Hatay province, was wiped out by the worst earthquake to hit Turkey in a century, killing at least 22,000 people. In the aftermath, I desperately tried to call Olga Al Bekkah, the sole Syrian-born member of a dwindling 15-person Jewish community there, whom I had visited a month ago.

While I waited for news about her, I recalled meeting Olga, 64, and her husband Daoud Cemal at their shop selling baby clothes in Antakya’s old market on a sunny, wintery day three days before Christmas. On their request, I had brought from Istanbul several kilos of kosher meat and a menorah, two things in short supply in the city that were also central to keeping their traditions alive. With no kosher butcher in the small town, Olga said, she once went six months without eating meat.

With jet black locks, a Mona Lisa smile, and a houndstooth scarf wrapped tightly around her, she spoke to me in Arabic with an unmistakable lilt from Damascus. We chatted as a group of Turkish women haggled with Daoud over the price for an outfit for a toddler. Then Olga led me from the bustling market to the city’s only synagogue, in possession of one of its few keys. The synagogue suffered significant damage during the earthquake.

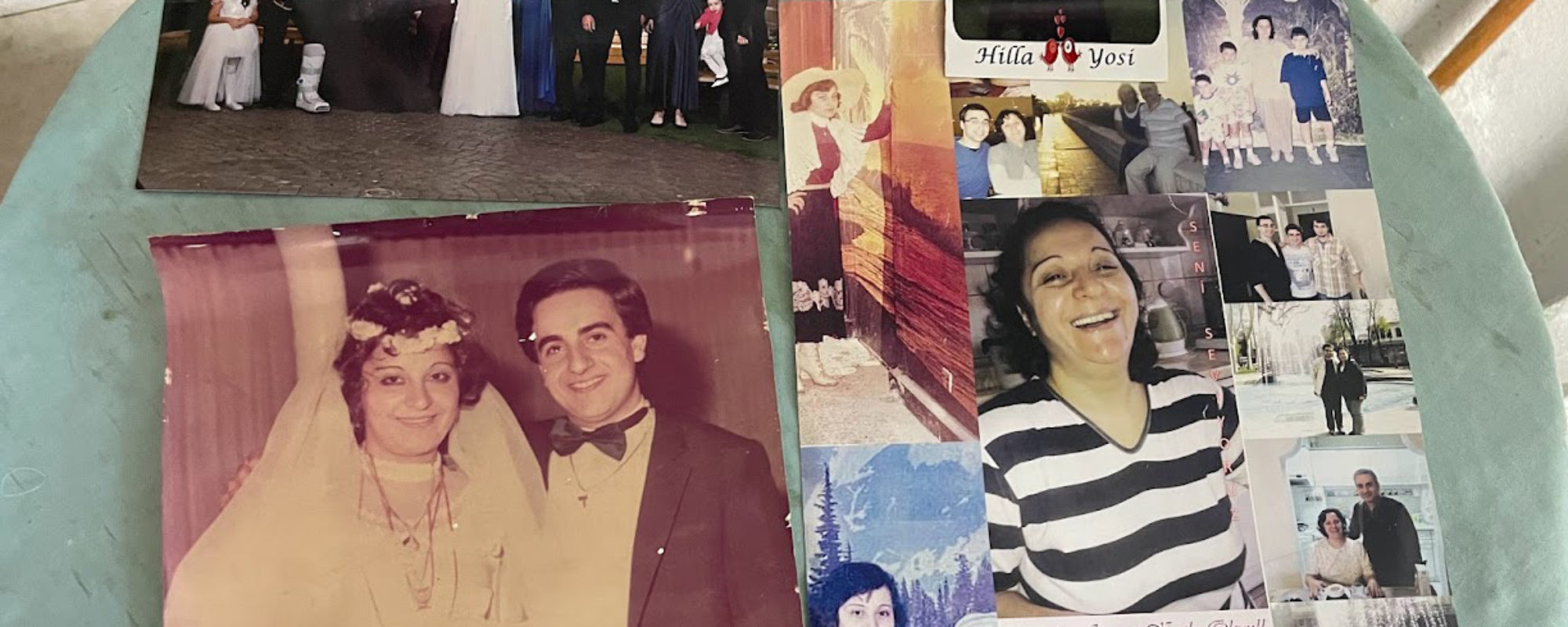

As quickly as she sat down, Olga launched into her life story, interspersing it with photos from WhatsApp, an animated confessional that spanned from Damascus to Antakya and from there to Brooklyn, Frankfurt and Tel Aviv. “I was born in the Jewish Quarter of Damascus as one of 10 children…” she began, telling a story of perseverance whose end I now feared may have finally come along with the traditions she had worked to preserve.

Syrians are now the world’s fourth largest diaspora, measured by the share of native-born population living abroad, largely due to the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011 that has become the largest displacement of the 21st century. But as Olga’s biography showed, various Syrian communities had already been dispersed around the world for decades, its members maintaining bonds through faith, language and family. Hers was just one of many snapshots of how the diaspora’s roots predated the conflict and how dispersion from the homeland has fostered new forms of identity.

Daoud was part of an Antakyan Jewish community comprised predominantly of Syrian descendants. In the early 1980s, he was in search of an eligible bride in Antakya, where the community was languishing. The decline had begun in the 1970s, when a wave of domestic political violence swept across Turkey, creating a difficult environment for the country’s minorities. Thousands of Jews fled to the economic and cultural center, Istanbul, or overseas to find a better life.

Antakya’s Jewish community never recovered. Daoud could not find a suitable match from the 500 remaining members. Taking matters into his own hands, his father handed a picture of Daoud to Tawfiq al Maleh, a merchant friend from his native Aleppo and head of the Aleppan Jewish community, asking him to keep an eye out during his travels home.

On al Maleh’s next trip to Damascus, he visited a Jewish community leader who was a school rector. As they were discussing Daoud’s search in his office, Olga entered the room. She was a teacher in the school. “This was God’s work, not man’s doing,” she told me with a wry smile.

Olga—named by her father after a Russian colleague he met working as a hotel accountant when Syria was still under French colonial rule—recalled her first conversation with Daoud, which took place over the phone: “I told him: ‘I saw your photo and would like to come and get to know you. If it is destiny, we will get married. If it is not our destiny, each of us will go their own way.’” During the year-long process it took to obtain Olga’s tourist visa for Turkey, they spoke each week.

In the second half of the 20th century, many other Jews were also seeking to leave Syria amid a tightening of their freedoms. Olga had also applied for a second visa. “If it didn’t work out with Daoud, I was going to travel to the United States,” she said. “No one knew I wasn’t planning to return to Syria,” she added. “Just me.”

Armed with both visas and accompanied by her parents, she travelled by bus to Antakya in December 1984. Daoud met her, and they married 15 days later, the first of many Hannukah miracles in Olga’s life, as she explained. “There wasn’t a mikvah,” she said of the ritual bath taken by a woman before a Jewish wedding, “so I had to use a bathroom instead.”

The area, formerly known as the sanjak of Alexandretta—an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire—had originally been under Syria’s Aleppo province before it was folded into France’s mandate after World War I. The new Turkish republic complained to the League of Nations about the safety of the ethnic Turkish population there, leading to the sanjak’s re-naming as the Republic of Hatay in 1937, an independent entity meant to be separate from, yet connected to Syria.

When a Turkish-French treaty sealed a friendship between the two powers, tens of thousands of Turks moved into the area before a 1939 referendum made the republic an official part of Turkey. The city’s denizens continued to look more toward the Syrian cities of Aleppo and Damascus than Istanbul or Ankara, however.

Antakya is located merely 40 kilometers from the Syrian border and 100 kilometers from Aleppo, but Olga’s life required an adjustment. Daoud’s family spoke Arabic in their homes, Turkish on the streets and Hebrew in the synagogue. “In Syria, I was a teacher,” she said. “Here, I became the head of a household.” But she settled into her new life. “I learned Turkish in six months,” she boasted. She had three sons and became an active member of the small but still vibrant Jewish community. Her sister followed her to Turkey and married Daoud’s cousin.

Olga raised her sons in a religiously observant environment. After nine years in the Turkish school system, they completed their final years at a Jewish school in Istanbul. Olga would visit regularly and send food packages once a month.

Across the border in Syria, Jewish life changed a lot after 1984. When the Hafez Al-Assad regime lifted a travel ban on Syria’s 4,500 Jews in 1992, the whole community, including Olga’s parents and extended family, emigrated to the United States. From there, many traveled further to settle in Israel. Since they were not allowed to sell property, they had to begin their new lives owning mainly suitcases and whatever valuables they could carry.

In Antakya, the dwindling Jewish community was not the only thing changing. Half a million Syrians settled in the Hatay province over the last decade. Most fled the civil war and have been trying to eke out an existence.

Olga felt connected to the recent arrivals. “If I see a Syrian, it doesn’t matter what religion, I am happy”, she said. She hired one Syrian newcomer to look after her 93-year-old mother-in-law, Adile, the oldest member left in the Jewish community.

Although Olga expressed devotion to Antakya and its tiny Jewish enclave, she did not expect to spend the final chapters of her life there. The Jewish diaspora expanded her own, her WhatsApp and Facebook feeds showing relatives and friends across continents and languages.

I recall Olga lighting candles on the fifth night of Hannukah before pulling out a photo album to show me her latest Hanukkah miracle: her son’s wedding the week before in Tel Aviv. She reflected on her own adventure to Turkey 38 years earlier, and where her journey would take her next.

“There is nothing left here for our community,” she had mused a month ago. “No kosher meat, no prayers, no festivals.” The biggest event planned for January had been a closed-ballot election to decide the next community leader. The incumbent Saul Cenudioglu was the only candidate.

There will never again be another Hannukah wedding in the synagogue with no mikveh. But this week, I finally received word that Olga and her family had made it out safely. Others were not so lucky, including Cenudioglu and his wife Fortuna, who died under the rubble. I can only wonder what Olga—like millions of other Syrians and Turks reeling from the disaster—will do next.

Top photo: Olga’s photos