Like any other spiritual or human endeavor, Islam is a plurality resounding in harmonies and, at times, disharmonies. I began learning about this faith and its people as a college freshman in 2001. As a journalism student at the University of Missouri, I was asked to reflect critically on media packages that paired footage of the terror attacks with images of women wearing hijabs, and to consider why such pairings were made, what they signaled to audiences, and how the same package ended up on multiple news networks.

Religious violence cannot be ignored, but we can question media coverage. For example, if a fourth of the world’s population is Muslim, and the world is mostly peaceful, why do media representations of this major world faith tend to whittle it down to a handful of newsworthy clashes?

I argue that the myopic focus on Islam’s violence is both misleading and dangerous. Misleading, in that it encourages us to equate Islam with the Middle East and North Africa (increasingly reduced to “MENA”), even though only around 20 percent of the world’s Muslims live there (62 percent reside in Asia).[1] Religiosity should not be limited by geography, a point being proven by an overdue non-European papacy.

The focus on Islam’s hotspots amounts to playing with fire: by focusing on the violence, we amplify the voices of violent minorities while muting the calls of those blessed peacemakers that exist among all peoples. Giving groups like ISIS the hearing they desire is dangerous, especially given that most of us don’t hear any other Muslim voice unless she is a victim of violence. We must question this choice.

And we do. Nearly every time I’m back home, a friend will ask something to the effect of, “why don’t Muslims speak up against terrorism?” The passive-aggressive undertone of the question rings in my ears, but I also register this hope we have that among those purported enemies, there are allies.

We know there are Muslim voices of peace we aren’t hearing. Our hearts haven’t been entirely hardened by misrepresentative media. But what we’ve been led to believe leaves us tone-deaf. We call out to the world’s 1.6 billion peaceful Muslims in a voice of accusatory helplessness.

With this Newsletter, I attune you to some of the (dis)harmonies of Islam, and challenge misconceptions you might hold. The story is set in the northwestern-most corner of Indonesia, which is closest geographically and ideologically to the Middle East — though still distant in both regards. Our characters — a historian, a breakdancer, and a gender studies professor — are all members of the world’s largest Muslim population: Indonesia’s 203 million Muslims comprise 12.9 percent of the ummah [the followers of Islam].

Indonesian Islam sounds little like the Islam of our TVs, which may be why we hear so little about the country save for the occasional remark about tolerance and religious pluralism. That will all change rapidly if the cacophony in MENA echoes over here. I hope this story makes clear that recognizing the harmonies of Islam is as important as being able to discern the occasional discordant note that resounds out here on the margins of “the Muslim World.”

The Story of the Stick

One blessed Friday back in 2015, men congregated for their weekly prayers at Masjid Baiturrahman in the heart of Banda Aceh. Prior to entering that sacred space, which had miraculously survived the 9.1-magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunami back in 2004,[2] each of these men took wudhu, or holy ablution.

They washed their right hand, then their left. They rinsed out their mouth and nose, and cleansed their face. They wetted their forearms up to the elbows, and then their head. They scrubbed their ears, inside and out. Finally, they let water run over each of their feet a few times. They did this with an intention of drawing themselves closer to Allah. They also did so because, for Muslims, this pre-prayer ritual cleansing is wajib [obligatory].

Every Friday, just before the sun reaches its zenith, Muslim men all over the world cleanse themselves thus, then line up in rows to listen to an imam deliver a khutbah, after which they pray together. Jummah, or Friday prayers, have been conducted in this way for fourteen hundred years.

But on this particular Friday, the 19th of June, the tradition was interrupted. A group of men occupied the masjid, demanding that the imam hold a stick while preaching. They argued that this way of conducting Friday prayers was an Acehnese tradition, that their cultural beliefs must be respected, and that prayers be performed as the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh[3]) was observed to have led them:

“We witnessed the Friday prayer with the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him), and while standing to deliver the sermon, he was leaning on a staff or bow.”

–Hakam bin Hazn Al Kulfi (as compiled by Abu Dawud Sulayman)

What complicates their claim is that no Qur’anic verse or utterance of the Prophet commands that the imam hold a stick, staff, or spear (or sword, as the Prophet was observed to hold during times of war) while delivering the khutbah. Therefore, the men’s assertion was less an act of rule enforcement than one of rule creation. According to Islamic theology, no rules had been broken.

But there are rules of the book, and there are rules of the land. And in Aceh, for centuries, the khatib [preacher] has always held a stick. What’s more, there is no debate that holding a stick is sunnah [encouraged]: performing the religious act as the Prophet Muhammad was observed to have performed it garners thawab [reward]. So if the khatib is Acehnese, will earn blessings, and will appease his congregation by holding a stick…why not just hold the darn stick?

Traditions, Modernity, and Wahhabism

“Traditionalists have used the mosques like battle gyms, aiming to control them for more power.”[4] This reference to Pokémon Go was a playful attempt — my friend’s third or fourth — to explain what happened with the stick two years ago, and why it mattered now, two months before the gubernatorial elections. I came to Aceh to gain a better understanding of how these elections will affect Islamic education, but in asking about dayah [Aceh’s religious schools], I kept hearing about the demands of the ulama [spiritual leaders of these schools]. Responses delivered me again and again to this story about holding a stick. I didn’t get why it mattered.

In every account of this story I heard, the group of men championing Acehnese traditions were cast as the bad guys for trying to enforce something that is not wajib. But when I asked why Acehnese preachers would refuse to participate in an Acehnese tradition that was sunnah, responses fell short of answers.

I decided to seek out my friend Baiquni, a self-described “historian and life-long student of scholars.” Bai is a new father, but in his spare time he teaches at two universities and occasionally delivers sermons, just like his father did before him. He tells me that the story of the stick is actually more a tale of tug-of-war, and that the background of the group of men shapes his understanding of their ambitions.

“Tengku Syamunzir bin Husein has a majelis zikir that has many followers. On Thursday nights at Baiturrahman, they have zikir, from after Isya until around midnight.” [Zikir is a spiritual activity, usually involving prayer beads, which is intended to hone the mind on the greatness of Allah.] (One of Tengku Syamunzir’s majelis zikir sessions can be viewed here.) By employing the Acehnese honorific “Tengku,” Bai has respectfully identified Syamunzir as a traditionalist ulama.

When Tengku Syamunzir first tried to get people together for zikir back in 2010, only eight people attended. But he kept at it, and when the group reached twenty-five people, they began moving masjid to masjid, growing each week. “Now thousands of people come on Thursday nights. They own Masjid Baiturrahman.”[5]

I ask Bai to clarify who “they” is. He identifies them, this moving group of zikir-ers, who are also the group of men keen to see khatibs carrying sticks, as “Aswaja” — ahlu sunnah wal jamaah. It translates to “the people of the sunnah and the community,” and is a reference to Sunni Islam. Bai then added one more detail, in deference to the group and its goals: “these men felt their space was being invaded, that their way of worship was being altered, by Wahhabists.”[6]

I’ve learned a lot about Islam over the past decade and a half, and I still associate Wahhabism with Saudi Arabia, Islamic radicalism, and terrorism. I was already leaning toward the guys defending their culture, and tell Bai that if they are confronting Wahhabist teachings, I’m only that much more inclined to side with them. I know that Bai, like 85 percent of the world’s Muslims, is Sunni, which leaves me confused — why do I sense that he disagrees with the actions of his own group?

Bai then defines the other group — the people being forced to hold the stick. He knows they aren’t Wahhabists. because he knows many of them personally — they are also professors at the local university, where I taught back in 2010 when I first met him. They’re being called Wahhabists because they studied abroad.

This bit of empathy frees me from the false binary that had ensnared me. There is not one group defending Aceh’s traditions and another ushering in some virulent version of Islam — there is a group of learned men who control Masjid Baiturahman, a group of men trying to make a religious rule of a cultural practice in an effort to usurp control of the masjid (which I would later learn rewards US$24 million in funding for maintenance from Aceh’s special autonomy budget[7]), and then there are a bunch of Acehnese Muslims like Bai who view the challenge as more political than religious, but say nothing lest they too are labeled as Wahhabists.

* * *

A few days later, I’m in Bireuen, sitting with friends who just finished their breakdancing competition. As so often happens in Aceh, the conversation has wound its way to religion. The hip hop account of the story of the stick matches others I’ve heard. But subsequent to my conversation with Bai, I’ve been mulling my original question — why not just hold the stick? Beyond receiving the blessings of Allah, doing so would take away a major argument from these traditionalist challengers, and safeguard that big pot of blessings from the State.

I pose the question with that addendum, presupposing that my hip hop friends lean modernist and may have some interesting insight. And for the umpteenth time, I am forced to remember that religiosity and politics don’t line up like they so often do back home.

Max, who teaches English and Qur’anic reading at a local dayah, answers in a mix of two languages (translations are italicized): “Because they get a different education, a foreign education, they don’t have enough knowledge of religion, because of the influence from there brought here…They don’t think about it, about who’s dominant here in Aceh, but the majority is Sunni, Aswaja…Maybe they want to bring new rules of Islam. Like, uh, Islam Liberal.”

I try to explain that he is operating from a false binary, that the stick doesn’t draw a line between Aswaja and Wahhabism. Max listens politely, unconvinced. Like Bai, Max is married (he keeps a picture of his wife in his wallet) and a father. However, unlike Bai, who got his masters degree in Turkey, Max attends a regional religious college. I consider how this positions each of them, and why Max buys this idea that studying abroad makes someone a Wahhabist. Why does he let the Western world into his leisure time but kept the Middle East out of his religiosity?

Max, a seeming mind-reader, says to me: “we also have to live in the world. There has to be balance.” But this just further perturbs my thoughts — how can an English-teaching breakdancer oppose foreign education? He must still be reading my thoughts, because he interrupts my (over)thinking to let me know that he needs me to understand something very important: although he and Saif participated in today’s breakdancing competition, they are actually skateboarders.

Over several more cups of coffee, we discuss skateboarding, which I know next to nothing about, then Acehnese education, which provides us with a bit more common turf. Max invites me to come visit his classroom and meet with the ulama of his school some time, and I mean it when I tell him I will. Before we part ways at the end of the night, Max says he hopes I’ll keep learning about Islam, but couples his hope with a warning: “Don’t get too close to JIL (Jaringan Islam liberal [the network of liberal Islam]) — it’s Wahhabi. We must stay Aswaja, the real and, insya Allah [God willing], the true Islam!”

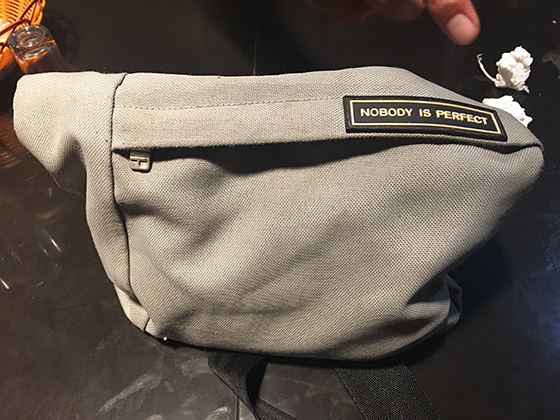

I sense a certain disharmony in Max’s way of looking at the world, which recognizes foreign education and liberalism as characteristics of Wahhabism. But then I think back on the associations I had been making with that word, Saudi Arabia, and terrorism, and I realize that we’re both basically using it as a slur. I wonder if Max is still reading my thoughts and responding non-verbally when he tosses his bag over his shoulder with its words readily apparent. He smiles at me as Saif hops on the back of his motorcycle, then they drive off into the night.

Unwanted Advances: the Role of Women in Aceh

The Islamic University of Ar-Raniry was the more conservative of the two places I worked when I lived in Banda Aceh six years ago. In a recent conversation, however, a friend told me the university is often criticized by traditionalists as being a door to liberalism and Wahhabism. The pairing of those words still sounds odd to me.

I am visiting the newly constructed campus today to meet with the woman who serves as the head of the Center for Child and Gender Studies. I am hopeful Dr. Inayatillah will articulate how the disharmony of Masjid Baiturrahman has reverberated out into the surrounding community — how political maneuvering affects the lives of the half of Aceh’s population who are absent from our story.

After brief introductions, we transition into a conversation about rules, religion, and gender. I know Islam isn’t just a set of rules, detached from culture and followed uniformly all around the world, but I am also aware that when Aceh makes headlines, it often has to do with the implementation or enforcement of syariah law.

For example, a town in Aceh banned women from straddling motorcycles in 2013,[8] and in 2015, unwed couples were banned from sharing motorcycles in North Aceh.[9] Challenging such laws is easily conflated with opposing Islam, so creating new religious laws disrupts power relations, just as we saw in the story of the stick. And because Aceh’s political class is about as male-dominated as a masjid during jummah prayers,[10] syariah law is slowly becoming more patriarchal than the Qur’an dictates.

But these are my observations, as a foreign white male. After sharing them with Dr. Inayatillah, she helps correct my misunderstandings: “Syariah law moves the conversation of lawmakers to clothing — pants versus skirt — but that’s just rules. It wasn’t that. Rather, women in Aceh have been domesticated by national ideologies — for example, the idea that women belong in the home.”

Her assertion that women have been marginalized not by religious law, but by national ideologies, intrigues me. I know enough about Acehnese history to know that long after Islam spread in the region, Acehnese women took on prominent roles as freedom fighters. Even today, schoolchildren throughout the archipelago learn about the tenacious leadership of heroes such as Cut Nyak Dhien and Malahayati. There was a time in Islamic Aceh were women had great power.

When asked how Indonesian independence reduced the power of the woman in Aceh, Dr. Inayatillah points to the advance of the national project. “After freedom, women started to be sidelined in Aceh. There were national rules around who could be panglima [a military commander], a politician, and so on.” She pauses for a moment to gather her thoughts, then shifts her focus: “Parents used to have to give their daughters a house. Men used to live with women, so in the case of a divorce, the man had to move out. But then parents started to just give their daughters land…now they don’t give their daughters anything.”

I never get around to explicitly discussing the conflict about the stick with Dr. Inayatillah, because over the course of an hour she has made a strong case for the argument that the cultural shifts have less to do with rules — legal or religious — than with the people who write them. Whether that be traditionalists proposing the holding of a stick, politicians instantiating bans on motorcycle riding, or nation-makers redefining the role of the woman, patriarchy lies behind them all.

Speak Softly and Carry a Big Stick

Perhaps you are curious as to what happened with the stick. Well, in the end, the khatib did relent and hold a stick while preaching. Some news coverage celebrated the defeat of the Wahhabists[11], while other news sites, also clearly favoring the Aswaja group, took a more reserved tone, noting that tolerance means stick-holders should be chosen as imams at least two Fridays per month.[12] Essentially, the stick-holders were chalking up their challenge as a win.

But then, four months later, their leaders met with modernist and other ulama at an Acehnese religious council meeting, where they collectively resolved that holding a staff was indeed sunnah [recommended], but not wajib [obligatory].

I would later learn that the stick-holders and the traditionalist ulama who represent them are politically affiliated with Vice Governor Muzakir Manaf, who was (or perhaps still is) a military commander of Aceh’s separatist movement. He is one of six candidates running for governor in next month’s election. I recall Max saying that if he wins, they will “resign ourselves to it. Because if Irwandi wins, (Manaf’s followers may make things) hectic again.” His friend, the other breakdance competition judge had added: “They are like mafia. We are just…we’re just regular people.”

In thinking about how to tell the story of the stick, that phrase stuck with me. “Orang biasa.” Regular people. When I first heard about the standoff at the masjid, I failed to understand who the people were, or what was at stake. When at last the the grandstanding at Masjid Baiturrahman became evident for what it was, I realized why labels like Wahhabism and liberalism could be conflated in Aceh just as readily as Muslim and terrorist are by some back home: it is easy to construct an enemy by remaining ignorant about who people really are and what they stand for.

Constructing binaries such as “Acehnese Islam and Wahhabist Islam,” or “peaceful Muslims and violent Muslims” deafens us to the harmonies and disharmonies of Islam and the world we all share. Too many of us know only the drone of reports about violent Islam that emanate from our TVs.

I hope this Newsletter has complicated your ideas about Islam, and made clear that for Muslims, religiosity is as much in conversation with other aspects of identity, such as race, class, gender, political affiliation, and nationality, as is the case for you and me. Recognizing our own internal contradictions is a first step toward resolving conflicts in the world around us. And as Max put it, “We want no more conflict. If no more conflict, we can go everywhere.”

But resolution will take action steps on the part of regular people like us…because as Dr. Inayatillah made clear, conflict isn’t the only thing that can restrict mobility.

“There has never been a war for war. Many nations have gone to war with no desire to conquer. They went to the battlefield and fell all to pieces, like the people of Aceh are doing today….because they had something to defend, something more valuable than death or life, winning or losing.”

–Pramoedya Ananta Toer (1980)

[1] http://www.pewforum.org/2009/10/07/mapping-the-global-muslim-population/

[2] In the aftermath, the masjid stood alone among the rubble as a testament to its construction or, for Muslims, as a sign of divine intervention by Allah. Either way, the pictures are captivating. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-12-26/baiturrahman-mosque-a-testament-to-acehs-survival/5977720

[3] “pbuh”, or “peace be upon him” (“SA”, or “sallallahu alahi wasallam” in Arabic), is a tag placed behind any mention of the Prophet Muhammad. As a high-profile blasphemy case is currently underway in Indonesia, I have opted to include this tag; I also do so to show respect to my Muslim readers. Henceforth in this document, be it presumed that I have said the prayer instead of written it.

[4] This source’s name has been withheld for the purposes of this article.

[5] In its 6 Oct 2016 report “The Anti-Salafi Campaign in Aceh,” the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict cited Ustadz [spiritual teacher], Harits Abu Nauful as saying “two years ago we started out with five students (at our pengajian), but now we have thousands, maybe it’s because some high-ranking officials joined.” The Aswaja movement should be understood to have many leaders.

[6] Here in Indonesia, Wahhabists tend to out themselves when they refuse to participate in praying at the graves of loved ones and celebrating the Prophet’s birthday, which they believe to be bida’a [inventions]. This cuts at the cultural traditions and familiality of many Indonesians, and for reasons such as this, Wahhabism is as detested in Indonesia as it is in the West — or perhaps moreso.

[7] See “Komisi IV” dpra.acehprov.go.id, 18 February 2016

[8] http://www.voanews.com/a/aceh-town-bans-women-from-straddling-motorbikes/1581819.html

[9] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32598761

[10] One noteworthy exception is Banda Aceh’s mayor, Iliza Sa’aduddin Djamal.

[11] http://www.muslimedianews.com/2015/06/kembalinya-masjid-raya-banda-aceh-dari.html

[12] http://www.acehterkini.com/2015/06/tongkat-dan-azan-dua-kali-di-masjid.html