I walk into the cabin and have to suppress a gasp. My friend Jon sits on the bed, his entire body covered in lumpy, bright red hives.

“My lips feel weird. They’re all swollen.”

“I gave him the allergy pill already,” Shannon, his partner, is unnecessarily tidying, something I have noticed she does when she is trying to demonstrate that she isn’t nervous. She came to our cabin ten minutes ago saying that Jon was complaining of a rash, and I gave her a suspiciously haggard-looking and years-old Benadryl that I found in the bottom of my purse. In that short amount of time, Jon had hopped in the shower and blasted his body with hot water, relieving the itch but releasing an alarming allergic reaction. Jon’s eyes look hollow and sunken in his brilliantly flushed face. I really don’t like that the swelling is approaching his mouth and throat.

I keep my voice as even as I can and I try not to stare: “Let’s get you another Benadryl.”

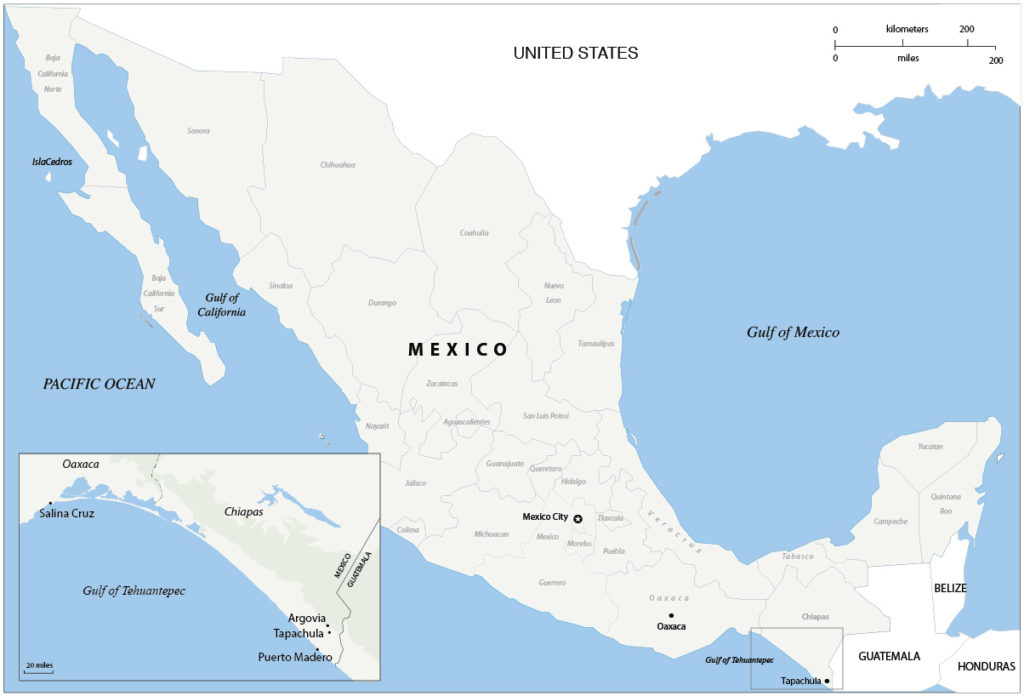

We are in the jungle-clad mountains of Chiapas, Mexico, and the thick black night just cloaked the last whispers of the day. The evening is still except for the hundreds of insects flitting around the cabin’s yellow porch light. We came up into the mountains in search of the story of coffee in a changing climate far from phones (cell and landlines) or medical care. To get here, we climbed out of the steamy flatlands of Puerto Madero, and through the narrow and chaotic streets of the state capital, Tapachula. As we gained altitude in the knobby mountains, we found relief from the heavy, humid air gathering for the impending rainy season. We wound up in the forest on a paved but sinuous road otherwise covered in jungle. Two hours away from any medical care, Jon is experiencing anaphylaxis, the body’s overdrive allergic reaction that can lead to fatal swelling of the chest and throat. Hopeful that our hosts might have more effective medicine, we make our way down the path lit with oil lamps to the main house of the lodge.

Inside the 100-year-old wooden structure, Jon’s eyes look even more bizarrely sunken in the blue-hued glare from the fluorescent lights on the high ceilings. After a look of alarm and a murmured conversation on the house phone, the concierge fetches allergy medicine. Jon looks at me, I nod, and he takes another dose. Hungry, but too nervous to eat, we slump into the one restaurant at the lodge. At an excruciatingly slow pace, a more normal color returns to Jon’s face over the next hour. As the scarlet fades, so does my tension.

What caused this near-death encounter? One of the smallest jungle residents: an ant. After Jon was bitten on the foot at the local watering hole only a couple times, we hiked uphill vigorously, then he mistakenly took a hot shower, which induced his anaphylaxis by sending his own immune systems into overdrive.

Approaching these mountains was dangerous enough already. The passage from Oaxaca to the Guatemalan border is the most dangerous sailing stretch in Mexico. Boats must follow the 265-nautical mile arc of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. Across this narrow strip of land at the bottom of Mexico, the Caribbean trade winds funnel west into the Pacific. These winds build breaking 30-foot seas in the Gulf’s center, so we must hug the shore. Staying close to shore has its own set of perils: if the wind blows hard, boat-crushing waves form within a quarter mile, so we must navigate the busy port of Salina Cruz, other vessels, and irregular and inconsistent sand bars that

could suddenly and catastrophically ground our boat. This is all tough to do with only two people trading shifts in the black of night, squinting at shifting lights on the horizon and guessing at blips on the radar screen while monitoring the depth sounder as the boat heels hard in 30 knots of wind. ‘Exhausting’ doesn’t even cover it.

Thankfully, our two-night passage of the Tehuantepec was tranquil. We sailed on the cusp of the hurricane season, when massive daily thunderstorms replace the ‘Tehuantepeckers.’ By day, we watched the clouds build, and at night the lighting tore through the skies — but at a distance. There are two seasons in this tropical climate: the dry season from December to May, called “summer,” and the wet season the rest of the year, the “winter.” We didn’t know yet how much these weather patterns have changed in only the span of our lives — or the importance of the seasonal cusp from winter to summer to the health of the local coffee plants and their economy.

With the boat safely tied to a dock in Puerto Madero — the only sheltered stop in Chiapas — Josh and I enticed our sailing friends on SV Prism, Jon and Shannon, into exploring the mountains. My interest in revisiting Finca Argovia didn’t just come from a desire to drink their rich, chocolaty coffee again: I wanted to hear how this industry weathers a changing climate.

As we drove away from the coastal plain for the first time in a year, I thought about the 3,000 miles of coastline we’ve traversed so far. I thought people would underscore the impact of the sea on the land. But residents often tell us the opposite. Coastal inhabitants state consistently that the health of the seas depends on the health of the rivers. In Chiapas, we were finally climbing into the mountains, searching for a riverine source.

The Benefits and Costs of Isolation

As we climbed the gentle slopes leading to the dense jungle, our cell phones mistakenly alerted us that we were in Guatemala, then lost service completely. We had to guess at turns until our little car groaned up the last steep incline to Argovia. White-walled housing for the seasonal workers shares the clearing along with tin-roofed warehouses that have stored coffee for a century. The main house has the wrapping porch and the square shape of a turn-of-the-century train depot. The only noises to interrupt the rain are the simple calls of jungle birds (they have to be simple and loud to bounce through the dense foliage.)

Finca Argovia, along with most fincas or plantations in the region, was founded over 140 years ago, when Mexico and Guatemala still hadn’t figured out their mutual border because of the remoteness and lack of European settlers. Mexico offered land registration in Chiapas to the agribusiness men in Guatemala starting in the 1860s. Adolf Giesemann, a German immigrant, purchased some of this land from a Swiss family. Although the Giesemann tract was modest, the collection of land grabs pushed indigenous farmers further into the jungle. They often returned to the coffee fincas as indentured servants, and many of their ancestors are the seasonal workers on the fincas today. The Mexican Revolution returned land to indigenous groups beginning in 1919, but the majority of the fincas remained tucked along the border. The German coffee growers were able to survive their remoteness and isolation because they had a market; Giesemann would sail once a year to Germany to sell his product and negotiate his price. Even today, Germany controls 50 percent of global coffee trade.

The region stayed largely cut off from outside events and politics for the next 100 years. Even when the PRI, the reigning party in Mexico for 70 years, offered government support for the coffee growers through INMECAFE, the National Coffee Institute of Mexico, the farms received no infrastructural support, like rail or roads, to get their product to market. During the rainy season, from May to November, there was often no access between the farms and the closest town, Tapachula. The land is so steep, and cleared land so prone to sloughing away, that roads often could not be rebuilt until the dry season.

Coffee lends itself to geographic isolation; it can be stored for a year with no adverse effects. The climate may be perfect for avocados, but they can’t wait for the end of the rainy season. Fortunately, the climate is also perfect for coffee. In the recent past, only twenty years ago, the wet season started with predictable regularity —within five days of May 5th, I was told by multiple farmers — and the soil, although only ten inches thick, bore the richness of ancient volcanoes.

Ultimately, the fincas’ isolation could not keep coffee growers safe from the vagaries of the international market. The last 25 years have been particularly rough on individual coffee growers in Chiapas, starting with the dissolution of INMECAFE. Next, prices collapsed internationally when the International Coffee Association (ICA) could not agree on an export quota in 1989 (basically because Brazil still wanted to export all its lower quality robusta variety of coffee, but the world, driven by the US market, wanted the higher quality Arabica.) Coffee, which is traded as a commodity, has been unstable ever since. Finally, the introduction of NAFTA further made the small growers uncompetitive — especially the thousands of farms smaller than Argovia’s 80 hectares.

The fourth generation of the German family of Argovia, Bruno, has therefore turned to tourism to preserve his plantation. Staff in matching embroidered shirts rush to take our bags, and we walk empty-handed past blooming lilypads that interrupt a trickling waterfall next to the main building and restaurant. Bird of paradise flowers peek their orange beaks out from huge, shiny leaves, and groundskeepers sweep away the seeds of giant Huanacaxtle trees overhead. The property’s minimal energy needs (there is no air conditioning) are met by a micro-hydropower installation that uses the water naturally tumbling through the property.

The four of us walk down to the pozo, the natural swimming hole at the bottom of the dirt road. The water in the stream is still a clear emerald green: the wet season hasn’t quite begun to muddy the flow with soil and silt.

A Few Degrees, A Slight Shift in Seasons, A Catastrophe

“Five years ago, production was high.” We’re standing with Bruno in the morning sun, sweating and peering down into a steep ravine that cuts through the heart of Argovia. Jon is fine except for a swollen ankle, and we all gather around our host, a tall man with kind, dark eyes. He’s a matter-of-fact businessman with the heart of a farmer, but he is emotional as he tells us, “then came roya.”

Roya is coffee rust, a yellow fungus that eats coffee leaves and turns the pink coffee berry a pallid gray, killing off the productive parts of the plant before the harvest. Rust first appeared 150 years ago in Africa, the birthplace of coffee, and made its way slowly to the Americas. In 2012-2013, it made a savage strike in Central America with unprecedented equanimity, devastating the coffee crop and the local economies that depend on it, from Panama to Chiapas. On Argovia’s 80 hectares, over 60 percent of their plants were lost.

The devastation was so fast and so complete that there’s a lot of local murmuring about sabotage. “It moved so slowly for so long; how could it travel so quickly? We knew about it in Brazil, so there’s no way it could get up here this fast.” Farmers, especially those struggling to be organic, suspect the pesticide industry rigged the collapse by intentionally spreading the fungus.

Even if this were the case, the perfect storm had brewed for a coffee catastrophe. To start, environmental conditions in 2012 were perfect for roya. Rust can sit dormant on leaves and wait for moderate temperatures and extra moisture. In 2012, there were unseasonable spikes in rainfall in April and June, and the rainy season started early that year. In addition, the average temperature didn’t experience its normal swing from hot to cool in the mountains — each day was a degree cooler and each night was a couple degrees warmer (Farenheit). As humans, we can barely notice these changes. But a fungal spore notices. And those three degrees were just enough to allow the roya to thrive.

Another coffee grower I spoke with, a certified organic producer named Sven Shalit, told me that it’s the seasonal variation that makes it increasingly difficult for the growers. Sven’s family has also been in the coffee business for a century, and their farm is about 60 kilometers away from Bruno’s.

“It’s become a roulette,” he says matter-of-factly. “Now the seasons are totally unpredictable: it rains when it shouldn’t, it’s dry when it should rain, we just don’t know anymore.” And the plants demand regularity.

In addition, in Argovia’s region, one storm at the start of the 2006 season dumped one meter of rain in two days, a weather event without precedent in the region. The downpour washed away not only crops but also most of the precious ten inches of topsoil.

The final blow was the coffee market and the realities of growing a new plant. As coffee commodity prices tumbled at the turn of the 21st century, most growers couldn’t take care of their crops as well as they used to—they just didn’t have the cash. Though rust resistant varieties of coffee were available, they were not planted; a coffee plant takes two to six years to produce any fruit, so crop turnover means multiple thin years that small farmers can’t afford.

“If we have been in crisis for 20 years, should we keep doing the same things?” Bruno gestures in the ravine in front of us, filled with native bamboo, tall legumes, ginger flowers, and a few coffee bushes. “That’s why we try to take our cues from nature now.”

Bruno started to bring tourists to Argovia 15 years ago, in part an attempt to pay his workers enough to keep them returning. Seeing the need to diversify still, he built on his passion and training as an agricultural engineer and started growing tropical flowers for sale around the country.

Bruno has started to think about coffee beyond the beverage. “We only use .1 percent of the coffee plants. That’s like if a cattle rancher only sold the filets.” Bruno speaks of extracting phenolic acid and caffeine from the fruit of the coffee plant.

As we walk from the sun into the coffee mill, Bruno tells us that they are replacing their four-step water mill — it slides water along a narrow concrete maze before the beans end up in tanks to ferment their fruit away — with more advanced Swiss technology that uses 95 percent less water. For the last two years, this region has felt the impacts of El Nino as a drought, which further aligns with the increasingly unpredictable weather. Last year, Argovia generated forty percent less energy from their micro-hydropower because they simply didn’t have enough water. Since tourism is now the main source of income for Argovia, Bruno had to start thinking about how he could possibly keep both sides of this business afloat if the drought continued.

I feel guilty about my slight sadness that the techniques from 100 years ago will be put aside. I love watching the beans sluice down their concrete trails, the quality beans sinking and rolling as the lesser quality float by. But their water supply is their livelihood as well as their electricity here — and they have to adapt.

The Watershed

On our sail here, we passed mangroves that fill the Chiapas coast. They are the deltas of the water that gushes from the coffee plantations in the mountains. The mangroves are home to few humans, but are the breeding grounds of millions of fish. The waters are a safer and calmer place for the tiny spawn of reef fish, jacks, and shrimp. The trees also ‘fix’ the carbon that we continue to belch into the atmosphere back into the soil, and they literally hold the coastline together. Even where a few beaches replace the mangroves, the stands of trees protect the beaches on their flanks from erosion by tides and waves. But mangroves are one of the earth’s most vulnerable natural systems: an estimated 578 square miles, or one percent of the total, disappear every year. More than 35 percent are already gone.

Coffee growing is a delicate balance: the plant likes the sun, but trees are necessary not only to fix nitrogen in the thin soil, but to keep that soil glued to the steep hillsides of the tropics. Farms that cut down too many trees not only fill the rivers with their soil and runoff and whatever cocktail of chemicals they have decided to use, but plants without nitrogen and sufficient soil simply can’t cling to the rock, and more soil rushes to the coast as more powerful storms pound the mountains.

This is where a changing climate sinks the knife in the heart not only of the coffee growers, but the plants downstream. “The amount of rain is the same, but the intensity is higher,” Bruno tells me — along with every cab driver or fisherman or store clerk I chat with in Chiapas. Researchers from Mexico’s Autonomous University, who used Argovia’s drying patios to set up instruments for their studies, can confirm this: the water from storms is hitting the earth with more force than in the past.

As rainstorms intensify, they deluge the mountain slopes. After the storm in 2006 that dumped a meter in two days, the soils from Argovia and all the surrounding plantations washed downstream to the mangroves. The sedimentation choked the roots and natural chemistry of the mixing fresh and saline waters. When this happens, whole complexes of mangroves are killed off or deeply altered, which in turn eliminates fishery breeding grounds. Many of the mangrove stands near Puerto Madero are now gone, taking with them the shrimp and fish that sustained the local diet and economy.

The People

The world drinks 6.5 billion cups of coffee everyday. In Mexico alone, four million people depend on coffee production for their livelihoods. Seasonal workers are paid by the quantity of beans they bring in every day. The hours are all the daylight available. Stretching and stooping to pick the coffee ‘cherries,’ then carrying the loads up and down the steep slopes, is backbreaking. The pay is atrocious, especially further south in Central America: workers make an average of $3.50 per day, but that drops to two dollars per day in low-yield seasons. If there aren’t enough cherries to pick, then families cannot afford to eat. Conservation International estimates that the rust epidemic threatened the food security of at least 150,000 families.

The Possibility

In 2013 in Central America, there was a fast and fierce response to the rust epidemic. Led by the organization PROMECAFE, numerous private and government organizations entered into an agreement that provided training, credit, and new crop varieties for farmers. Growers and coffee cooperatives have also managed to find alliances with direct trade coffeehouses in the U.S., Europe, and even Mexico itself.

For example, in Los Barriles, Baja California Sur, Mexico, a young couple from Washington state opened a tiny coffeehouse. They bring their Pacific northwestern coffee sensibilities and quirkiness to the Mexicans, Americans, and Canadians mingling at the garage-door-style window of the bar as they drink coffee with their feet in the sand. They travel to the Mexican mainland every year and buy all their beans from one grower — exactly from whom and where, they won’t say, coyly guarding their prized selection.

These mano-a-mano alliances give the money directly back to the growers and harvesters. Although the big fair trade organizations and certifications, like Fair Trade USA, have been shown to be largely ineffective in promoting social equality[1], the direct traders show more promise. Climate change hits the little guy the hardest, but the small organizations and coffee houses that attempt to ameliorate the field-to-cup price gap are sustaining a new market that isn’t linked to global commodities.

Sven, the certified organic grower down the road from Bruno, agrees, although he trades on a slightly larger scale for his 300-hectare farm. “The only reason I survive is because we have buyers with a fixed price contract. They don’t care about the C-market in New York. Every three to four years we come together and discuss pricing.”

“Otherwise, I’d be long gone.”

Bienestar

We stand with Bruno, our bodies huddled together near the espresso machine, ensconced in jungle at the open air restaurant as we sip our coffee. Bruno started roasting his own beans a few years ago, cutting out another middleman, and he tells us the difference between the medium and dark roasts is just a few seconds.

I like the thickest brew, the stracciato, while the rest of the group prefers a slightly milder taste. Bruno grins and tells us that it’s all the same coffee, just taken from different points in the pour from the espresso machine. We chat together about coffee culture, the enjoyment of slowing down to touch a cup to one’s lips. It’s the bebida de vida, he reminds us: in times of cholera, people couldn’t drink the water, but they could drink coffee. “So it became the foundation of socialization,” Bruno says. His gaze stretches into the quiet canopy of trees under a gathering afternoon storm, looking at the nearby farms, many of which are invisibly sprayed with chemicals. Invisible to us, anyway.

“Everyone has an excuse to do what they do, but what is the cost in the long run?”

The stream continues its run through the finca, gurgling beneath us, carrying pieces of the mountains to the sea. Bruno talks about bienestar, the notion of well-being. To him, success is measured in bienestar, not the pursuit of money or status. I notice the tremor in his hands when he picks up his coffee, and I wonder about his health. I’m tempted to feel jaded, that the pursuit of well-being is for those with enough money to desire it. But the coffee gives me a moment to pause and wonder what it might be like if well-being could be the goal not only in coffee production, but downstream for the drinkers.

“In the tropics, everyone is in poverty, but we live in richness.” Bruno shifts his weight and sets his cup firmly and gently on the counter. “We need to change the values on which we stand.”

“When kids visit Argovia, we ask, what is your goal? And if it’s not wellbeing, then they are lost.”

I put my coffee to my lips and take a slow sip.

[1] Haight, Colleen. “The Problem with Fair Trade Coffee.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. Summer 2011. http://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_problem_with_fair_trade_coffee