May 2015

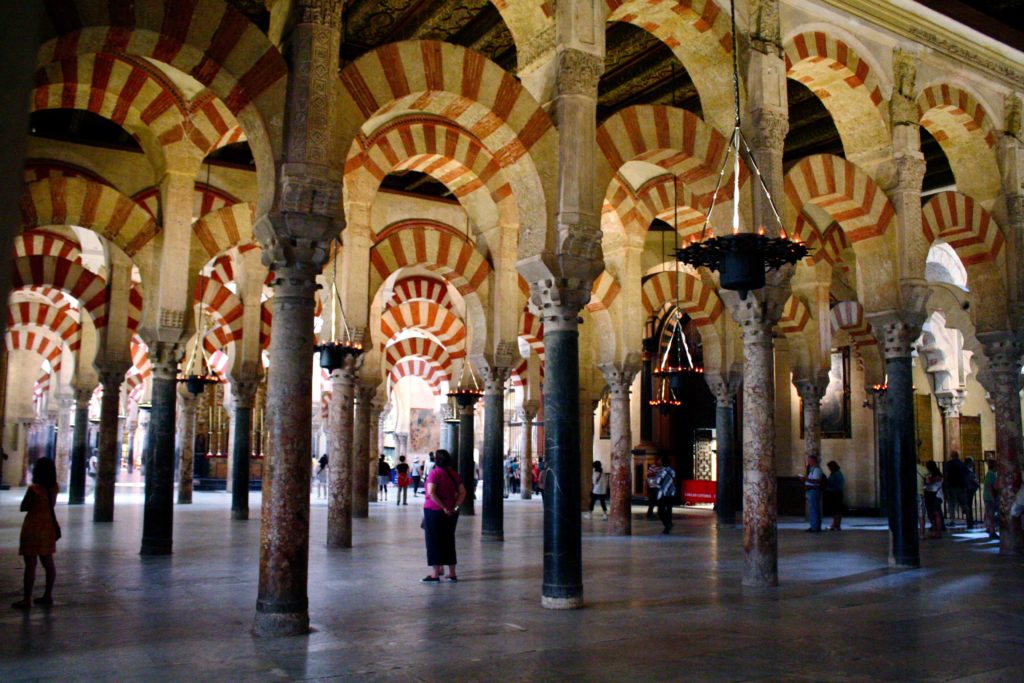

The first time I saw the Córdoba Mosque-Cathedral was during a vacation to Spain. I remember walking into the building, and feeling a sense of awe as I stared up at the rows of striped arches, dimly lit by elegant brass lamps. Nestled in the heart of the mosque is a cathedral bathed in natural sunlight, with vaulted ceilings carved from stone, creating a unique architectural fusion of Catholic and Muslim, East and West.

My friend Jasmine, a Sudanese Muslim from the United Kingdom, had a very different experience. When she visited the mosque last winter, she too was awed by the arches, the historical significance of the monument, and the golden Mihrab. But unlike me, she was unable to lose herself in the experience of the mosque-cathedral. A petite woman with dark chocolate skin and a headscarf, she is conspicuously Muslim, and the moment she stepped through the door, she felt watched. A guard in a crisp white shirt, hired by the church to ensure the Christian holy space was respected, was staring at her. She noticed he was always nearby, and wondered if he was following her. Finally, as she neared the Mihrab, he tapped on her shoulder, startling her. Gesturing at her headscarf he told her sternly that Muslims are not permitted to pray inside of the Cathedral. She left shortly after, feeling angry, sad, and unwelcome.

According to Isabel Romero, a Spanish Muslim convert and the director of the Córdoba-based company, Halal tourism, many visiting Muslims have reported similar experiences in recent years. “The Mosque-Cathedral is supposed to belong to all of us. For Muslims, it is one of the most important religious sites, next to Mecca, representing a golden age of Islamic civilization” she explained. “But the Catholic Church is trying to deny that heritage, and claim the site as theirs.”

The Cathedral-Mosque of Córdoba is has been called the most important Muslim heritage site in the Western World, drawing 1.5 million visitors each year. Also known as the “Great Mosque of Cordoba,” the site was built on Visigoth ruins in 785, signaling the beginning of seven centuries of Muslim rule of Spain and Portugal. Soon after, Córdoba would become the capital of the Umayyad caliphate, which spanned from Syria, to much of North Africa. As the religious center of the Caliphate, the mosque would come represent a golden age of Islamic Spain, and contribute to Córdoba’s image as a center of culture and learning — replete with libraries that boasted more books than the Vatican, universities that attracted scientists and scholars from around the world, and running water. It is also remembered as a time of convivencia when followers of the three great religions, Catholics, Jews and Muslims, lived together in peace.

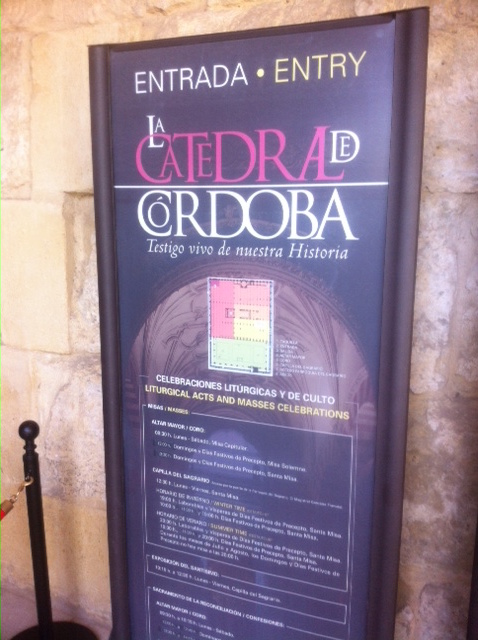

Now, the mosque has become the site of a fierce conflict, pitting local activists against the Catholic Church. The former accuse the Catholic church of erasing the structure’s Muslim past. Today, “mosque” is omitted from the literature distributed on the site, and the audio-guides (produced by the church) treat the seven decades of Muslim rule as an “intervention.” Exploiting a loophole in Spanish property law, the Church is also attempting to claim official ownership of the monument — and, unless challenged by the local government, will become the sole proprietor by 2016.

For Romero, however, the struggle for control over the image and ownership of the mosque goes directly to the question of Spanish identity. “Right now there are two Spains, divided by two visions of what it means to be Spanish,” she explains. “One sees Spanish identity as fundamentally Catholic — tracing our roots back to the reconquest by the Catholic monarchs. The other vision of Spain is essentially multicultural, celebrating our diversity, and the history of convivencia, where we recognize and incorporate the influences of Romans, Celts, Jews and Muslim as a fundamental part of what it means to be Spanish, and give it equal importance to our Catholic heritage.” Romero pauses, as though looking for the right words. “This second vision is threatening to the Catholic church. The Great Mosque is one of the greatest symbol of Spain’s multicultural past — and one that the Church wants to erase.”

* * *

The conflict over the name of the mosque-cathedral became world news last fall when the monument temporarily disappeared from Google maps. One day, the title “Mosque-Cathedral” was prominently displayed for all to see. The next day, the word “mosque” had disappeared, leaving “Cordoba Cathedral” in its place.

The change provoked immediate and resounding protest. A group of Spanish citizens, outraged by the omission, mounted an online petition on change.org demanding that the word “mosque” be reinstated. The petition notes that “since 2006, when the Church matriculated the monument, we have witnessed an attempt of judicial, economic, and symbolic appropriation of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba by the Bishop of Córdoba. Part of this strategy was to revoke the term ‘mosque’ for the sole word ‘Cathedral,’ erasing with one pen stroke a fundamental part of its history.”[i] Within weeks, the petition had accumulated more than 50,000 signatures, and today has close to 500,000. Last November, Google reinstated the previous name “Mosque-Cathedral,” which had been used since the 1980’s.

Miguel Santiago is a Córdoba native, and the co-founder of the Plataforma para la Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba, patrimonio de todos (Platform for the Mosque-Cathedral, heritage for all) the organization behind the petition. A short, middle-aged man who likes to talk with his hands, Santiago is a local schoolteacher. Though a DEVOUT Catholic, I recently met him in his house, a traditional Córdoba courtyard home.

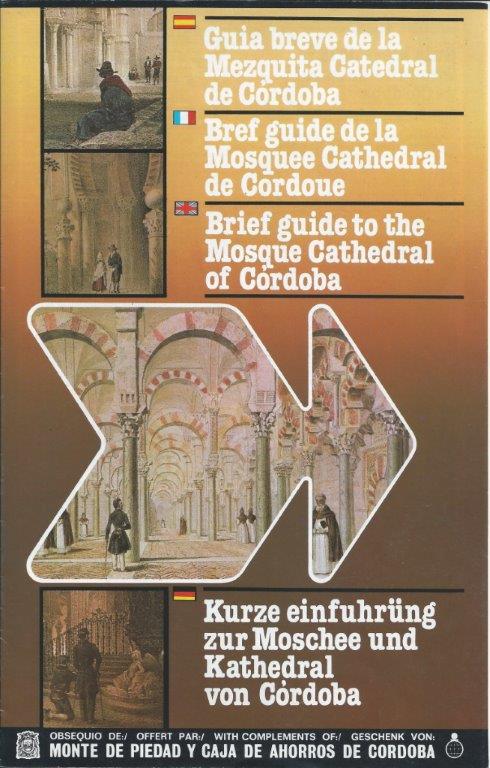

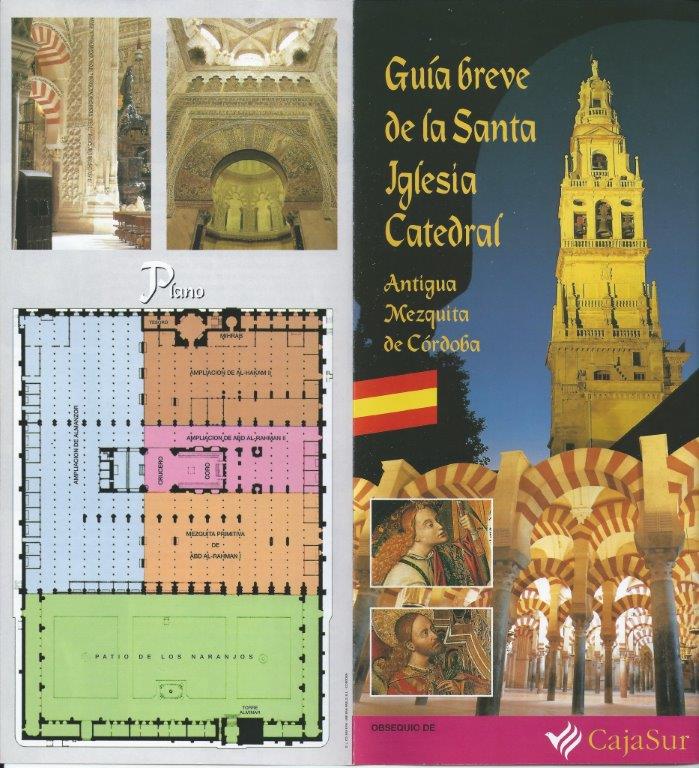

Though a Catholic, Santiago has become one of the Church’s greatest critics. According to Santiago, last year’s brief Google omission was not a one-off event, but part of a steady campaign by the Church to establish control of the monument over the past 30 years. Removing a heavy binder from a shelf behind him, he flips to a brochure of the monument, published by the Church in 1981. “Here you can see that its Islamic heritage is emphasized,” he said, pointing to the title “Mosque Cathedral,” a term that recognizes its shared heritage. In the description printed in the brochure, the first sentence reads, “The Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba — according to F. Chueca is the first monument of all the western Islam and one of the most impressive of the world.” The remaining text provides nearly equal weight to its Muslim and Christian heritage. The next brochure, published in 1998, calls the site “Santa Iglesia Cathedral,” and in much smaller letters “former mosque,” which is described in the text as “primitive,” with no further elaboration on what was “primitive” about it. The brochure emphasizes the Roman and Visigoth influences to the architecture of the mosque, which was “built over the Christian Visigoth basilica.” By 2010, according to the brochure, the site is referred to simply as “Córdoba Cathedral;” the 700 years of Muslim rule are an “intervention.”

Today, the first thing visitors encounter is a glass panel on the floor revealing excavated mosaics below. According to the Church, the mosaics are the original floor of the church of St. Vincent, built by the Visigoths, which the Muslims destroyed to build their own religious center. However, this version of history — treated as fact by the Church–is highly debated by academics and historians. “We don’t actually know if there was a Visigoth cathedral there or not. The archeological findings are inconclusive,” Santiago said. “But the Church treats it as fact. The church is rewriting history. And most tourists will never know — they’ll just accept the church’s version as truth. It’s a disgrace.”

Even more worrisome to Santiago is the Church’s attempt to take legal ownership of the space by exploiting a loophole in Spanish property law that allows the religious body to register public property. As the registrants of the property, all revenue earned through admissions to the monument go to Rome. The provision also allows the Church the right to continue to control the onsite image of the monument.

According to José Juan Jiménez, a Catholic priest in Córdoba who often leads Sunday services in the Mosque-Cathedral, the furor over the name is overblown. “In reality, the monument is used as a cathedral. It hasn’t been a mosque for hundreds of years,” he told me from his office across the street from the monument. He also believes that the argument over ownership has become unnecessarily heated. “The church has managed the property since the 13th century,” he said. “Registering it is just a formality.” He acknowledges that the name-change could negatively impact Córdoba’s tourism industry — but says that such things are “not of concern to the Church.”

But Santiago believes it’s not just about tourism. “This monument has so much significance in today’s world, which is full of religious conflict,” he said. “The mosque-cathedral is a symbol of convivencia. It’s a symbol of conciliation, and of intercultural and religious exchange, at a time when we need such symbols more than ever. Because in the same monument, where Muslims prayed for hundreds of years, Christians now pray. This is what the mosque-cathedral has to offer the world — to be a lighthouse of unity, a place of encounter and peace. It is, in its essence, a symbolic key to this unity. We need such symbols now. Unfortunately, we are not taking advantage of this opportunity, and it’s becoming the opposite: Just another conflict between Christians and Muslims.”

* * *

Santiago is not the first to invoke the powerful symbolism represented by the Mosque-Cathedral. In her article analyzing the contested history of the monument, medieval scholar D. Fairchild Ruggles notes that “the building, as the single most powerful emblem of Islam in Iberia, has come to represent much more than a mere development in architectural history. As the first and only surviving Spanish congregational mosque, it ‘stands in’ for a lost, or simply repressed, Hispano-Islamic identity. This identity is claimed both by Spanish citizens and by others whose claim, though distant, is nonetheless aggressively—sometimes violently—asserted.”[ii]

Even al Qaeda recognizes the symbolic power the building commands: In a video released on the internet, Osama bin Laden’s second-in-command, Ayman al-Zawahri, invoked the former glory of the Cordoba mosque to call for a new reconquest of al-Andaluz, when he ominously said: “O our Muslim nation in the Maghreb…restoring al-Andalus [is impossible] without first cleansing the Muslim Maghreb of the children of France and Spain, who have come back again after your fathers and grandfathers sacrificed their blood cheaply in the path of God to expel them.” ISIS has also mentioned the mosque, echoing al-Zawahri’s call for reconquest. Such videos prompted immediate response from Vox, an anti-Islam political organization in the north of Spain, who published their own video warning of the dangers of a violent Muslim reconquista.

Other groups have appropriated the image of the Cordoba mosque-Cathedral for their own, more peaceful ends: Eight years after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 in the United States, a group of Muslims calling themselves the “Córdoba Initiative” sought to build a 13-story Islamic community center two blocks from ground zero. Intending it to be a “platform for multi-faith dialogue,” the projects’ organizers wanted to call the building “Córdoba House,” after the “model of peaceful coexistence between Muslims, Christians and Jews”. Even politicians have invoked the powerful symbol. In his speech at the University of Cairo in 2009, President Obama also cited Cordoba as an example of Islam’s “proud tradition of tolerance.” Within Spain, businesses have exploited the country’s Islamic heritage to create a booming business of “Halal tourism,” welcoming visitors from Muslim countries to witness the majesty of Spain’s Islamic past. Even the Spanish government has drawn on the country’s history to position themselves as a key negotiator between the Western Europe and Arab states.

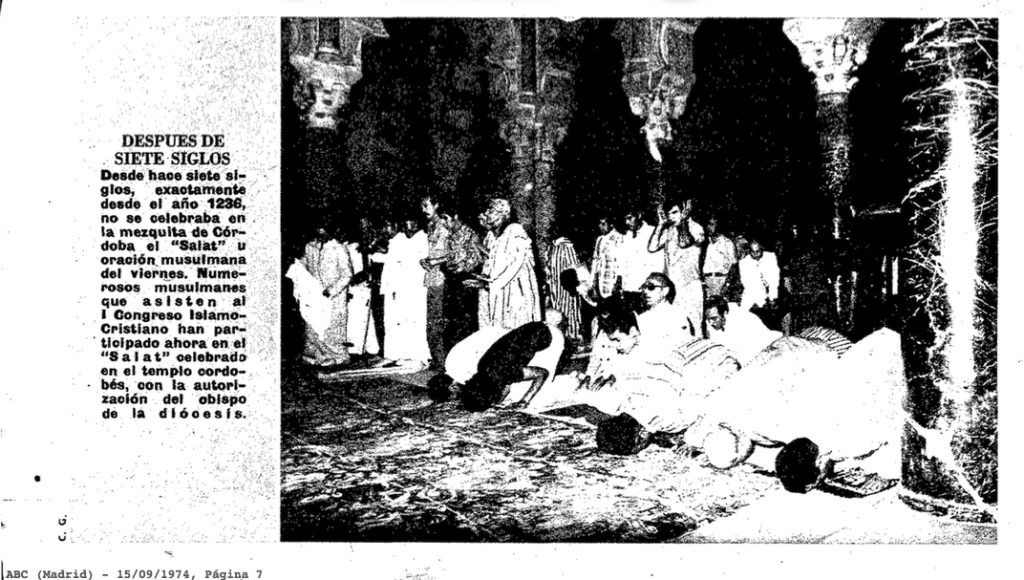

Although the Church has kept a firm hold on the monument since the reconquista, they have not always forbidden Muslim prayer. In 1974, during a three-day interreligious conference on Christian-Muslim relations, the former bishop of Córdoba permitted Muslims to practice salat (Musli prayer) in the monument in recognition of the monument’s shared heritage. The photographs of Muslims praying in the mosque for the first time in 700 years quickly circulated around the world. Four years later, in 1979, church authorities again opened the space to allow local Muslims to celebrate Eid al-Adha. The church would allow Muslim collective prayer four more times in the mosque-cathedral between 1980 and 1995.

The church’s tolerance would be tested in 2004, when Mansur Escudero, one of the leaders of Spain’s Muslim converts, requested that the Church allow the monument to be transformed into “a multi-confessional space of worship, where the one and only God could be worshipped in all its forms.” He reassured the church that Muslims “do not want ownership, exclusivity, or to change the name of the Córdoba Cathedral, we only want to be welcomed in to worship God.” He would eventually pursue his request in Rome, formally petitioning Pope John Paul II. In his appeal to the Pope, Escudero described the Mosque-Cathedral as “a symbol of universality that the city wishes to reclaim as a positive identifying mark, as a symbol of free expression and pluralism, open to all forms of thought and worship, a place of meeting and peace.”[iii]

The Vatican rejected his request. Escudero later protested the church’s decision by laying out his prayer mat in the street in front of the entrance to the monument, and praying just outside the church grounds. “It was his way of protesting the injustice of the decision,” explained Romero, who knew Escudero well, and considered him a mentor. Escudero died in 2010. “No one has taken up the cause since his death.”

For Escudero and other Muslims who wished to open the facility as an ecumenical space for Muslim-Christian prayer, the issue was less about the right to prayer, and more about how Spain’s growing Muslim population would treated by the church and the state. Romero believes that allowing Spanish Muslims to pray in the mosque-cathedral, which is used regularly by Spanish Catholics, would be a first step in accepting Spain’s Muslim heritage as an essential part of Spain’s current culture and identity, in contrast to the current narrative, which continues to treat Muslims as “outsiders” and “invaders”.

The scholar Ruggles agrees, observing, “I think the controversy is not really about prayer at all, because in actual practice, anyone can utter a quiet prayer in the Cathedral, communing with whatever version of God their religion teaches them to worship. But Muslim prayer, which demands oriented standing, bowing, and prostration, announces its difference visibly and actively. It resists assimilation to any order other than Islam. Therefore, the struggle in the Cathedral-Mosque is a struggle to cope with the changing demographics of Spanish society, to cope with difference, and specifically, with Islam.”

Romero, who was born Catholic, converted to Islam shortly after meeting Escudero. “I had always been Catholic, and I never questioned that. It was only after meeting Manzur, and learning about the Muslim tradition in Spain, that I realized how much of my culture has come from Islamic heritage. It was like rediscovering a part of myself I never know was missing,” she said. For Romero, her “re”-conversion to Islam revealed to her that many Spanish traditions have Muslim roots. For example, she remembers her grandmother washing multiple times a day in the ritualized manner that Muslims do before prayer, and saw Muslim customs reflected in Andaluz hospitality. This realization made her believe that Spain’s Muslim heritage is not an outside, alien force — but a repressed part of very Spanish identity — a repression she strongly believes has been extremely damaging not just to Muslims, but to all Spanish.

To Romero, the recognition of Spain’s Muslim heritage goes beyond understanding her cultural roots. She believes that Spain’s integration of its Muslim past into its current identity is the first step in healing a gaping cultural wound. “We Spanish have always been at odds with ourselves,” she explains. “Ever since the reconquista, when the Catholic kings tried to unify the country s through religion, and force us into one identity. That has led to so much pain — to the expulsion of the Muslims and the Jews, and the Spanish inquisition, the Spanish civil war, the conflict in Basque country and now Catalonia’s desire to separate from Spain. What if we accept that we are not one uniform people, but we are in fact, multicultural? There is room within Spanish identity for all of these things. What would happen if instead of being threatened by that difference, we allow ourselves to be strengthened?”

[i] https://www.change.org/p/google-no-retir%C3%A9is-la-palabra-mezquita-del-nombre-de-la-mezquita-catedral-de-c%C3%B3rdoba Translated into English.

[ii] D. Fairchild Ruggles, The Stratigraphy of Forgetting: The Great Mosque of Cordoba and Its Contested Legacy, Contested Cultural Heritage 12 (2011)

[iii] Guia, A. The Muslim Struggle for Civil Rights in Spain: Promoting Democracy through Migrant Engagement, 1985-2010. Sussex Academic Press: Eastbourne. (137)