PARIS — Last month, Senate President Gérard Larcher sat down with the magazine Paris Match for a series of interviews to discuss a subject that never fades from the national debate: Islam. “The majority of religions took a conciliatory route with laïcité,” he said, referring to France’s particular vision of secularism. “When it comes to Islam, it’s not in its nature to do so spontaneously.”

Larcher wasn’t talking about the typically controversial headscarf or the burkini, although there’s been no shortage of related controversies in recent months, from a sustained outcry over a running hijab to a new episode of an old dispute over some Muslim women’s preferred swimwear. He was referring instead to the government’s attempt to create a “French Islam,” echoing President Emmanuel Macron, who last year pledged to “set down markers on the entire way in which Islam is organized in France.”

That may sound like another of the young, reform-minded president’s radical ambitions. But it’s hardly unprecedented; Macron and Larcher are simply trying to succeed where past governments have failed.

Successive administrations since the 1980s have aimed to create a “French Islam,” with the dual objective of better integrating the country’s estimated 8 million Muslims and curbing the spread of Islamist extremism. Paradoxically, past attempts to transform Islam in France into an Islam of France have further involved foreign governments—a phenomenon known as an Islam consulaire, or “consular Islam.”

That notably included the origin countries of the majority of French Muslims—the former colonies of Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, as well as Turkey—as reflected in the leadership of the French Council of the Muslim Faith, known by the acronym CFCM, that then-Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy created in 2003. But the gamut of foreign influence also includes Gulf countries, notably Saudi Arabia and Qatar, which have heavily invested in Islam across the West—helping spread their orthodox interpretation of the religion—and enjoy close diplomatic ties to France.

That’s largely because of France’s strict vision of secularism, which not only separates church from state but mandates the government’s absolute non-involvement in religious affairs. Its role strikes many as paradoxical. “The state can’t interfere in the management of religion or theological questions,” Olivier Roy, an expert on Islam and radicalization, told me. “Yet for 30 years, French governments have tried to do just that. The whole project is a profound contradiction.”

Since Macron’s original announcement, the plan has been buried amid months of Yellow Vest protests and a series of high-profile scandals. But it’s hardly disappeared. In the meantime, an ideologically charged and often ego-driven tug-of-war has emerged, as divergent figures—all of them men—jockey over who can best represent France’s Muslims.

The scope of foreign influence

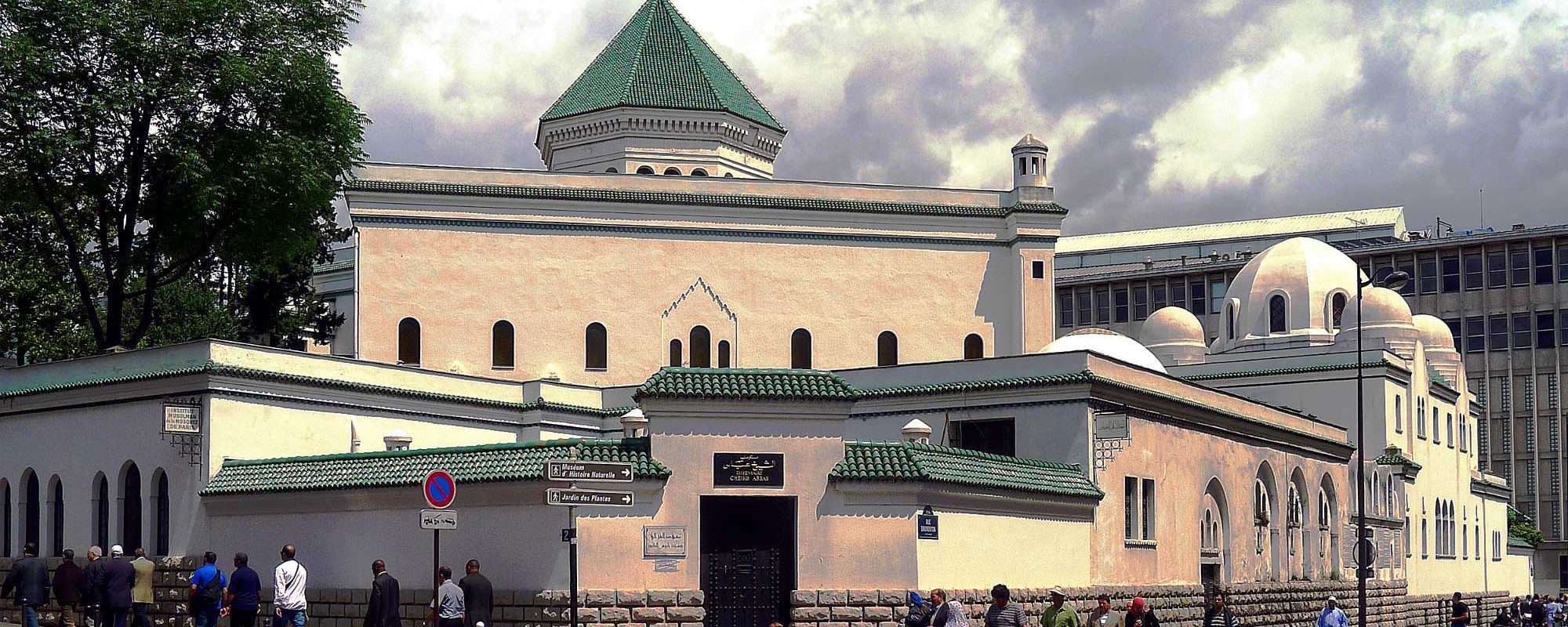

France’s major Islamic structures have clear ties to Muslims’ “countries of origin.” Algeria finances the Grand Mosque of Paris, which distributes funds to affiliated mosques across the country. Turkey, Algeria and Morocco have also sent significant numbers of imams to France, Interior Ministry figures show: In 2015, then-president François Hollande signed a deal with the Moroccan monarchy to send French imams to a training center in Rabat, and Turkey has invested in a host of religious and cultural organizations around the country, especially under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

French officials and many Muslim leaders find those foreign links problematic. In the CFCM’s case, it’s a question of credibility. “The CFCM was a forced institution that created a foreign Islam in France—a Turkish-Maghrebi Islam,” Tareq Oubrou, the Grand Imam of Bordeaux and a central figure in the current efforts to “restructure” the religion, told me.

It’s clear that most French Muslims don’t identify with the organization. Barely a third even know what it is, according to a 2016 survey; many I’ve interviewed have never even heard of it. “The main criticism isn’t that the CFCM represents foreign countries, it’s that they’ve failed French Muslims altogether,” said Marwan Muhammad, a prominent Muslim activist and the former president of an anti-discrimination group called the Collective Against Islamophobia in France, the CCIF. “Muslims say, ‘you need to stand up for us.’”

Some fear that external influence, and especially foreign imams, leave France vulnerable to radical interpretations of Islam. But experts warn against overemphasizing the link. “It’s foolish to say that if an imam comes from the Maghreb or wherever else, he’ll spread Salafism,” Bernard Godard, who served as the Interior Ministry’s in-house expert on Islam from 1997 to 2014, told me, referring to the literalist interpretation that has inspired some jihadi movements. “We need to recognize that Salafism is well-established in France.” Indeed, the majority of the perpetrators of the attacks that have hit France since 2015 have been French or European nationals.

The CFCM also rejects the government’s focus on taking distance from “countries of origin.” I met Anouar Kbibech, the president of the CFCM, at the organization’s offices in southern Paris. It was the end of the day and he seemed tired, his tie loosely knotted and shirt untucked, or maybe he’s just grown weary from the same conversation. “We need to demystify the notion of a ‘consular Islam.’ Of course Muslims have origins in other countries; I’m Moroccan, and I’m not going to deny my origins,” he said. Concerns over radicalization are misplaced, he added: “It’s not about financial transfers from Muslim countries to this or that mosque, or this or that association.” He laughed. “That’s just not how it happens—it goes through far more clandestine routes.”

The issue itself isn’t the mere presence of foreign actors, according to Oubrou, something he attributes to both France’s bilateral relations and Muslims’ inevitable ties to their countries of origin. But the financial aspect gets more complicated: “Funding needs to be transparent and without conditions,” he told me, noting that imams or mosques might receive backing from foreign powers under the pretext that they’ll advance a certain interpretation of religious texts. “It’s the narrative that we need to control,” he said, noting that it’s not just about speech that explicitly incites hatred or violence. “It’s about a discourse that provokes a rupture with the larger society, that’s divisive.”

If the goal isn’t just to fight radicalization but better represent French Muslims, many of whom were born and raised in France, there’s a case to be made for taking distance from foreign involvement. “Of course the CFCM would oppose the plan because they’re Algerian, Moroccan, Turkish—they want Islam in France to remain a foreign religion,” Roy told me. “But the younger generation doesn’t have those ties. This is for the third generation—to allow them to manage Islam without foreign links.”

What Islam, and for whom?

Which Muslims would this new, revamped Islam represent? At nearly 10 percent of the French population, they’re hardly a homogeneous bloc. “It’s always implied that a French Islam would be a moderate Islam, one that opposes terrorism,” Roy said. That’s where things get more complex. “What does it mean for a religion to be moderate, or for a person to be moderately religious?”

For Oubrou, the imam, it’s about finding an Islam that aligns with French values. “We need to find a way to make Islam meld with the West—with France,” he told me.

That question—what vision of Islam, and for which Muslims—is at the heart of the debate. Some balk at the very idea of a top-down approach to managing their religion, which they consider patronizing, part of a larger, neocolonial impulse to domesticate their faith. “They want to create a media-friendly Islam, a livingroom Islam, one that’s palatable to the authorities, who will select ‘representative Muslims,’” M’hammed Henniche, the president of the Union of Muslim Associations of Seine-Saint-Denis, a district northeast of Paris with a substantial Muslim population, told me. “It’s a façade.”

‘It’s always implied that a French Islam would be a moderate Islam, one that opposes terrorism… [But] what does it mean for a religion to be moderate, or for a person to be moderately religious?’

But Henniche’s gripe raises an important question: When France talks about Islam, what is it actually talking about? For Oubrou, debates around Islam pertain less to the faith itself and more to Muslim identity. “Today, there’s an identitarian logic that’s suffocating Islam,” he told me. That’s why he’s calling for a centralized religious authority, mirroring those that exist for Christianity and Judaism, that would “speak exclusively in the name of religion.”

His goal is to control the religious narrative, in large part by fostering a new generation of better-trained imams.

“Someone can become an imam from one day to the next,” he said. “They’re not trained, they don’t understand the complexity of theology, of our world.” Although that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll promote extremist ideas, “they might defend a medieval Islam, one that isn’t viable today. We need imams who will reconcile Islamic tradition with French society.”

One problem is financial. “An imam’s status is extremely low in France,” Roy said. “Young, observant French Muslims with advanced degrees won’t become imams—they won’t settle for 500 euros a month,” he said. That incentivizes a “cheap Islam, largely financed by Salafi networks.” Accordingly, the question of funding is central to what initiative might emerge.

The imam and the financier

With that financial approach in mind, Oubrou has teamed up with Hakim El Karoui. Together, they seem to have the government’s ear when it comes to the future of Islam in France. A graduate of the prestigious École Normale Supérieure and a former investment banker, El Karoui mirrors the president in his elite trajectory. He’s clean-shaven and trim, and he’s not a practicing Muslim. When I met him last year the upscale Hotel Bristol in the moneyed 8th arrondissement, he seemed right at home.

“Fundamentally, I’m proposing one thing,” he told me over coffees and a plate of petit-fours, which remained untouched throughout our two-hour conversation. “That we shift the responsibility to French Muslims, who have no interest other than France.”

He aims to empower a demographic he calls the “silent Muslims”—members of the middle class and elite who don’t find themselves embroiled in clashes over laïcité. That, he says, will help drown out the Muslims he sees as hostile to integration—and extremists. “On social media or in the public debate, who talks about Islam, about religion? The Islamic State on the one hand, and Salafis on the other.”

El Karoui’s vision draws on his financial background. He calls for “more financial autonomy,” which would involve taxing important businesses in the Muslim community—halal meat and travel to Mecca for the hajj—in order to fund other religious activities, such as imams’ education. Accordingly, he created the Muslim Association for French Islam, or the AMIF, which officially launched in April. Those funds, the argument goes, would help fund religious activities.

Oubrou would be at the center of a centralized, theological authority, alongside the AMIF. “It would be a consortium of imams,” El Karoui said, that “will be able to talk to Muslims and non-Muslims alike. The radicals will call them sell-outs, but they’ll be heard by the greater public.”

But some Muslims take issue with El Karoui’s definition of what constitutes a “radical” and reject his assimilationist approach to Muslim identity. His detractors say he conflates any expression of religiosity with Islamism, the political ideology that has sometimes inspired violence. He has, for example, called halal meat a “social marker”—not a religious requirement—that reflects the “penetrations of Islamist behaviors.” When I asked if his vision for French Islam would include women who wear the headscarf, he was firm: “It’s a simple fact that the veil doesn’t represent Islam, that it’s an identitarian symbol,” he said, describing it as an emblem of Islamism. Some criticized a report he authored last summer for the Institut Montaigne think-tank that classified 28 percent of French Muslims as “authoritarian secessionists,” based on survey questions that assessed attitudes toward laïcité and religious freedom.

Oubrou, for his part, largely agrees with El Karoui’s read. Choices like the headscarf and halal, he says, have gained “excessive importance” in Islam. “Many people associate the veil with Islamism, incorrectly, but the Islamists were the ones who made it so prominent,” he said. Women who wear the headscarf, he added, “don’t know that what they’re wearing is associated with, and was promoted by, the Muslim Brotherhood.” The same applies to halal, he said: “If you eat only halal meat, but you drink wine and don’t pray, I’d call that a sociological marker that has nothing to do with religion.”

Statements like those have made some Muslims distrust Oubrou, who they allege plays into national hysteria over Islam’s visibility in the public space; when I relayed such concerns, he insisted, on the headscarf question, that “women should be able to dress how they want.” In his latest book, he calls on French Muslims to be “discrete,” which some have interpreted as a capitulation to the calls for assimilation that have been a source of tension since the 1980s. Oubrou called those reactions a complete misunderstanding. “The majority of Muslims don’t understand theology,” he told me. “Discretion doesn’t mean disappearance. It’s a spiritual question—to be present, to be discrete, not to be ostentatious.”

The activist and the community

Marwan Muhammad is the most vocal opponent of El Karoui and Oubrou’s approach, and he has a plan of his own. The son of an Egyptian father and Algerian mother, the sociologist and statistician grew up in Paris and the banlieues and made a name for himself as the president of the CCIF, the anti-Islamophobia organization. He no longer leads the group, which gained visibility during the summer of 2016, when mayors across southern France attempted to ban Muslim women from wearing burkinis on beaches and at pools.

“The government’s first reflex is a colonial one—we decide, we pick, you follow,” he told me over hot chocolates at a Latin Quarter café earlier this year. “Their interest is security, to maintain control of the religion, to watch, to regulate.”

Muhammad is charismatic with an intense gaze, and speaks in well-crafted paragraphs in near-perfect English. He’s emerged as something of a cult figure among a certain segment of French Muslims, especially amid the spike in hostile rhetoric that followed the spate of terror attacks that hit France in 2015 and 2016. He’s accordingly made his fair share of enemies—figures on the right and left who contend that his focus on discrimination gives credence to the narrative of victimization that Islamist groups use to shore up support. Some allege that he has ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, partly due to his past relationship with the controversial Islamic scholar Tareq Ramadan, whom multiple women accused of rape last year.

El Karoui is stuck in an old paradigm about Muslim integration, Muhammad says. “In the ’80s and ’90s, there was an assumption that as the younger generation became more empowered economically, socially, they’d move away from religion,” he said. “But for many of them, it’s been the opposite.”

Last year, Muhammad launched his own project to rally French Muslims—an initiative he called “the consultation.” He distributed an online questionnaire to assess the state of Islam and Muslim life in France, and gathered over 27,000 responses. He then organized daylong meetings with communities across the country.

His findings confirm the need for some sort of revamp: Only 7 percent of respondents said they identify with the CFCM, and 63 percent expressed a desire for a national structure to better organize and represent them. On the ground, he told me, participants lamented a lack of professionalism and reluctance to challenge discriminatory media narratives about Islam.

“The expression I heard often was this notion of ‘inclusion tranquille’”—“relaxed inclusion”—he said. “There’s a sense of ‘we want to be part of society, so stop asking us to justify or prove it.’”

Muhammad, along with some 30 other collaborators, envisions a locally derived national “platform,” which he calls “L.E.S. Musulmans.” A grass-roots antidote to the AMIF, Muslim communities would pool their resources and know-how to create a representative association independent of institutional constraints. He says he already has some 300 mosques and associations on board; its president and treasurer are women. “We have imams and accountants who can tackle hate speech and improve financial transparency,” he said.

When it comes to preventing radicalization, he agrees that “there’s a genuine security threat.” But he doesn’t think the current approach, or what El Karoui promotes, will work. “We can keep doing what we’re doing, breaking doors, raiding homes, watching tens of thousands of people,” he said. “Or we can be much more analytical, more targeted—engage social workers, mosques, stakeholders at the grass-roots level, who are part of an ongoing relationship that isn’t limited to security.”

It’s that comprehensive approach that he defends, taking issue with Oubrou’s emphasis on separating religion from culture. “Islamic organizations are necessarily hybrid,” he told me.

It’s clear that Muhammad, with his local engagement and public image as an anti-Islamophobia activist, sees himself as more credible than the rest. “When I wake up to work for the platform, my goal is empowering Muslims, responding to their needs.” In contrast, he views El Karoui, and to a lesser extent the CFCM, as beholden to external interests. “The CFCM has two stakeholders: The countries of origin and the French state,” he said. “They’ll say anything the government likes in order to maintain their status as ‘notables,’” he said, which limits their ability to criticize policies he considers discriminatory, like counterterrorism laws or the 2004 ban on religious symbols in public schools.

Muhammad says El Karoui and the AMIF cater to “the French state and public opinion—the general public opinion, not Muslims.” That logic, he argues, won’t improve social cohesion or Muslims’ sense of belonging. “El Karoui wants to reassure the public by picking representatives who say, ‘we’re not a threat, we’re not anti-Semitic, all that,’” he said. “But that won’t fight racism now or in a generation. It’s not about how ‘good’ of a citizen you are—it’s the fact that we’re citizens, not criminals.”

I pitched Oubrou’s pitch—that the AMIF and its reallocation of funds could facilitate a better religious experience for Muslims, with well-funded imams, mosques instead of makeshift prayer rooms, and the state’s backing, which could ease tensions. “Sure, if you buy the idea that the elite knows better,” he said sardonically, describing their message as “You’ll give us your money, from halal and from the hajj, and we’ll redistribute it where we see fit.” He doesn’t buy it. “If you read El Karoui, that means an ideological counteroffensive—by the imams he chooses, like Tareq Oubrou, who fit his worldview, who see all criticism of the state as defiance.” That won’t work, he said, “because Muslims are diverse, so their decision-makers should be, too.”

The other side doesn’t exactly praise him, either. “Marwan Muhammad has a personal project,” Kbibech, the CFCM president, told me. “He goes on his adventure around the country, he writes the questions, he shapes the answers, he analyzes them. His questions are oriented.” (Muhammad denies that his questions are biased; they were reviewed by a scientific committee that includes statisticians, demographers and sociologists).

“Marwan takes an activist approach, an identity-driven approach,” Oubrou told me. “He focuses on Islamophobia at a time when society is afraid of Muslim communautarisme,” he said, referring to the derisive term used to describe multiculturalism or identity politics, considered inimical to social cohesion. “That’s not going to work.” But for Muhammad, the barrier to integration is less about discretion and more about tolerance.

Out with the old

What’s clear is that change is on the horizon and that the CFCM is on its way out. There’s been some talk of a reform to the 1905 law separating church and state, with the aim of facilitating more transparency and separating religious and cultural activities. Those potential debates have been pushed until “after the summer” in the flurry of the Yellow Vest protests and the European elections, and they’ll undoubtedly be controversial.

But for now, there are some apparent indicators of where things are headed.

In late May, Interior Minister Christophe Castaner broke with tradition by declining to attend its annual iftar—the ritual meal to end the month of Ramadan—claiming he was “above [its] internal quarrels.” The CFCM was furious.

Instead, Castaner went to Strasbourg, where he joined Abdelhaq Nabaoui, a young chaplain at a regional hospital, for his community’s iftar. Nabaoui wasn’t just some anodyne pick—he had a falling-out with the CFCM last year, when the organization revoked his status as its official hospital chaplain after he joined El Karoui and the AMIF.

It seems, then, that the government has made up its mind. But Muhammad remains confident. “We’re working hard, we have thousands of supporters, for the first time in history, we’re bringing Muslims together and breaking barriers,” he told me. “If you don’t want to support us because you’re too afraid to upset the right, or the Republican left, then suit yourself. But we’re going to make this happen.”

I asked Oubrou how he saw things playing out. He laughed. “It’s all about credibility,” he said. “As they say, may the best man win.”