January 19, 2016

LAGOS, Nigeria—In early December, Christmas materialized across Lagos. Office buildings transformed into gleaming beacons of the season, bedecked in detailed patterns or whole sheets of twinkle lights. Street vendors hawked Santa hats. Parties proliferated. Crime spiked. Urban transplants worried how they would finance a flamboyant family reunion on their return to the village. Others resigned themselves to a Christmas far from home.

The cosmopolitan diversity in Lagos keeps it forever connected to the rest of Nigeria, yet it is unquestionably distinct. Most Lagosians are not from here. Many Nigerians living outside the city are drawn to its cachet, its markets, and its port. Ninety percent of the country’s imports come through Lagos. Goods then travel innumerable spidery paths across the rest of the country in the rucksacks of countless individual entrepreneurs.

Caroline Ekoja is one of them. She is a jovial, small scale trader who deals in perfumes and urban street wear.

She came to Lagos twice in December. The bubbling seasonal spirit was not confined to the city. She was one of the conveyors of the consumerism of the holiday.

She set out one morning to visit her perfume supplier. She waited until Saturday in an attempt to avoid Lagos’ notorious traffic. But still, the journey took four hours.

She started in a “keke”, a small, shared tricycle taxi. The keke driver dropped her in front of the church at the Church Mission Society intersection, called “CMS”, near a major bus terminus on Lagos Island. She asked where she could get the bus for Mile 2 and he pointed her down a street toward the Balogun market and central mosque. I pointed her in the opposite direction, toward the bus loading zone.

“This Lagos, even if you are lost, some people will try to confuse the little that you do know,” she said of the misdirection.

Under the bridge, she trekked through the dusty lot toward a bus conductor shouting “Mile 2! Mile 2!” His cries mingled with the cacophony of potential destinations intrinsic to Lagos’ transport hubs. There are no signs, but the “danfo” buses have standardized loading areas and there are crowds of men hustling to direct passengers.

She entered and waited for the bus to fill. Beads of sweat collected, lifting and shifting her perfectly painted brows, lips and lashes. With a blue acrylic nail, she daintily pushed a line of condensation away.

Finally, the bus filled. Impatient passengers called the conductor, the man who had advertised the bus and taken the fares. But he couldn’t find the driver. So all the passengers filed down and entered a second danfo, this one somewhat smaller. “This one dey tight” she said. The knees of the passengers behind indented her back.

A fuel scarcity meant oil tankers were queuing at the port. The traffic jam bled into the expressway and surrounding neighborhoods. The route to Mile 2, a major transport hub in western Lagos became a circuitous tour of Ajegunle. The bright yellow bus passed on the wrong side of the expressway, skirting a toppled motorcycle, then twisted and turned through the impoverished neighborhood.

At Mile 2, Caroline climbed onto an “okada” motorcycle. The biker weaved its way through the series of traffic jams that surrounded the bus stops then sped up on the open road.

Finally, windswept, she got down on the side of the highway and boarded another, smaller motorcycle. The bike took her down the exit ramp and pulled up to a strange sprawling plaza. Called “trade fair” the market was first inhabited by an association of spare auto parts dealers. They were later joined by jewelry, cosmetics and beverage vendors. Situated on the West African Corridor, the road that leads from Nigeria to Benin and further westward, retailers from around the region come to stock up in the shops here. In front, small-scale vendors set up tables beneath bright umbrellas. Advertisements for creams, deodorants and beverages plastered the walls of the complex. Caroline walked through the sunbaked concrete entrance, then ducked into a small, cool, shaded pathway. She passed shuttered stores and languid beverage wholesalers before entering a perfume shop.

The small room was lined with glass cases packed with a mosaic of bright perfume boxes: Hugo Boss, Ralph Lauren, Yves Saint Laurent, and Jessica Simpson. As she cooled beneath a fan, she tried some new scents.

“This one is very strong,” the saleslady told her. Caroline murmured her appreciation.

The owner of the shop, a man named Charles recognized and greeted her. He has been in the perfume business since 2002. His brother lives in Florida and buys stock when it is on clearance to ship over.

Though she checked some new offerings, she knew the specific scents she needed. The “Smart Collection” is the cheapest, and she bought five. The bottles are enclosed in a rectangular box with “Smart Collection” printed on the top. A thin cardstock sleeve advertising Diesel, Burberry or Givenchy slides to encase the box. These are the obvious fakes and she bought them for 1000 naira (US$5) each. She also bought higher quality perfumes, Giorgio Armani and Lalique Encre Noire. It took 10 minutes for her to gather her 15 picks, for a total of 59,000 naira ($295).

On her way out of the market she wandered through the hair supply stores, past walls of weaves and wigs. Then she retraced her many steps. Two motorcycles, two buses and a keke later she arrived back to her friend’s flat.

For such a quick errand, she spent all day on the road. When she returned home she sighed. She said that next time she would call Charles to order, transfer money to his account and have him send the perfumes on a bus. But two weeks later she came back to Lagos and repeated the trip.

The journey is arduous. But perfumes are precious.

Among a certain set of Nigerians, perfume is seen as an essential part of an outfit. People keep perfume in their cars, desks and bags to spray just before entering a meeting or party. Perfume is a common “dash”, the colloquial term for a gift or bribe. Tenants give perfume to their landlords when the rent is late to soothe vexation and buy time. “Ogas,” Nigerian slang for powerful bosses, give perfume to young businesswomen in a common blurring of a professional relationship. Lower-middle class Nigerians wait anxiously for an influx of cash to purchase a respectable perfume.

“They wear it so people know they are wearing it, so people will ask ‘oh wow I like your perf what’s your perf?’” Kelechi Anyanwu, an economist and editor, explained. By asking about “perfumes” I was already demonstrating my ignorance of “perf” culture.

Anyanwu was explaining the economics of Caroline’s informal trade. For a market to function there must be supply and demand. An affable scholar, Anyanwu was breaking down the demand side of the intra-Nigeria perfume trade.

I asked him why in perfume markets the primary selling adjective I heard was “strong.” Not subtle, nuanced, or layered, not woody, spicy, or floral, just, “strong.”

“In a tropical area when it’s strong they believe the fragrance will last,” he said.

Most of the perfume is marketed as designer, but is actually knockoff. There is a wide spectrum of knockoffs, imported largely from China and Dubai.

“You go to Dubai, at the airport you’ll see the knockoff is one side, the real one is another side,” Anyanwu continued.

The difference between the real and the fake is mostly how layered the scent is. And how long it lasts.

The knockoffs “just won’t last you like the original designers,” Caroline explained. With the originals, “you can take it for the whole day…[and] you can still perceive the smell.”

Thus, the preference for “strong” smells. If the smell is powerful, the idea is that it will linger.

The knockoff perfume commerce is part of a broader market of fakes in Nigeria. “Anything that is properly packaged in Nigeria sells,” Anyanwu said, “make people believe and then they pay.”

But the knockoff market is not so simple. Some people think of designer wear as a goal. For them it’s important to access the real thing, the expensive status symbol. There is a race to constantly perform newness, comfort and luxury, particularly in the public sphere. For others, there is an understanding that most of what you find in the Nigerian market is not actually Versace. It is a style in itself. Fake Versace—at times spelled “VERSAGE”—is such a prevalent and wide reaching aesthetic it almost loses its allusion to the Italian luxury brand.

“I think…it is no attempt at dishonesty necessarily, it’s just kind of the language used to describe the style. So if someone is saying CK [Calvin Klein] whatever, I assume that what they’re saying is this is a scent that is meant to be like CK. It’s not that everyone is really claiming it’s legit CK, they’re just using it to describe the scent in the same way that people who say they are selling converse, they don’t actually mean it’s Converse, they mean that when you buy this you are getting a pair of canvas sneakers with rubber soles that are meant to look like Converse,” said Shelby Grossman, a PhD candidate at Harvard who is researching informal markets in Nigeria.

At the same time, some people do crave the real designer goods. Some upper class fashionistas in Lagos name-drop like it’s a greeting. Aspirational members of lower classes might switch from the new Chinese goods to used clothing imports. Olumide Abimbola, a Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Germany, studied the supply chain of used clothing from the UK through the Republic of Benin and into Nigeria. “If they want to buy a real Tommy Hilfiger shirt they would buy second hand clothing; not just because it’s cheap, sometimes it’s more expensive than normal China stuff.”

In a 2012 paper, Abimbola wrote about his fieldwork in the UK. “When I offered to help them in the sorting, I was reminded that as a Nigerian, I should make sure that I do not select any item of clothing that had any blemish, because it would end up on the bodies of my Nigerian brothers and sisters.”

The knockoffs may be poor quality, but they look fresh.

For Caroline, as a small time trader, taste is of the essence. She is a walking advertisement for her wears. As such, she has impeccable street style. It is largely casual: she layers plaid tops or neon mesh blouses over tight jeans—some with artful tears. But she is always youthful and trendy. She is one of the ambassadors of this urban aesthetic, conveying it along the well-trod trade routes from the metropolis to the satellite. She procures her goods mostly in Lagos, though some items come from Abuja, and carries them to her home state of Benue.

Because she deals in taste, Caroline hand selects every item that she sells. She slogs back and forth to Lagos, a 20-hour day of travel each way, to bring the perfumes and clothes she knows her customers in Benue like. She makes her money on her stamina and mobility.

This kind of in-person trade can look crazy from an outside perspective. Why not order goods and resell them? Meredith Startz, an economics researcher at Yale is studying the question along with Grossman. They focus more on international trade routes, but the motivating factors are parallel to the domestic in-person trade. She found that people travel to verify the goods they are ordering, since there is little recourse if their suppliers try to cheat them.

But they also travel because of taste. “When you buy goods in person you’re getting a better sense of what’s actually available. And we think that that might be especially important for products like clothing or maybe perfume where there is a lot of change in the fashion or the technology of the goods you want to buy. So the set of stuff is kind of constantly turning over and you need to go yourself to check out what’s available right now, what patterns are out there, what’s cool, what’s in fashion, what’s the best technology right now.”

And the numbers are huge. The Lagos Trader Survey[1], a 2015 study of 1,400 traders managed by Grossman and Startz, found that two-thirds of traders were traveling for in person trade.

The journey from Lagos to Benue is long. Caroline packed her perfumes and clothes into a single large backpack. After rousing at 5 a.m., she took a cab through the sleeping city to the Iddo bus terminal. It was pitch dark, but she passed a bustling market. Candles and battery-powered lights illuminated stacks of tomatoes and wheelbarrows nearly overflowing with phone chargers and headphones.

The cab pulled up next to a series of driveways with vans jutting out toward the street. Benue Links, her go-to bus company was closed that day, so she listened to the crowd of young men promoting different buses. “AC bus! Leaving now!” They shouted over each other. She followed one into the driveway for the Royal Top bus company.

She waited for the first bus to depart as the sun rose bright orange and round through the dust and smog. A small “I pass my neighbor” generator chugged, fueling a single lamp and emitting thick fumes. Kids wore bright Sunday style dresses for the journey. The crowded driveway was littered with deep, checkered bags called “Ghana must go” a reference to the sudden expulsion of undocumented Ghanaian immigrants in the 80s. Families packed all they could into the temporary containers and fled west. Now the bags are used for all types of less ominous transport.

The first car finally loaded and departed and the process recommenced for the second bus. Once the passengers packed in—three per row except for the way back where four adults and three kids crammed in—the driver stacked all the luggage onto the side, blocking the exit door. All day, when the bus stopped for bathroom breaks, the passengers crawled over the benches and each other to exit through the trunk.

A freelance preacher blessed the journey. The driver waited an hour in a fuel queue to top up. Then at last the bus rolled out of Lagos.

They crossed Osun, Ondo, Edo and Kogi states. At one point the driver pulled onto the opposite side of the highway and drove on, honking to warn the oncoming traffic. At a junction, a federal road safety commission officer waved him back over to the correct side of the highway. The driver crossed, but 100 yards later took a rutted path back to the wrong side. Shortly after, he sailed past a checkpoint set up on the other, correct side of the road. Caroline explained that the buses often do this to avoid being held up by the officers. “We are too packed in,” she said, “there will be a fine.”

“The challenges of moving goods from Lagos to the hinterland are very, very enormous,” Anyanwu the economist said, “apart from the transport cost you will meet various checkpoints on the road.” There are customs checkpoints, police checkpoints, army checkpoints and road safety checkpoints. Most of them demand small bribes before they let vehicles pass. “Where is my own?” and “Merry Christmas” were common coded phrases the authorities used when asking for the small fees.

The journey continued north east across the country, until she arrived in Otukpo, a town in Benue that Caroline planned to visit for Christmas. There she switched vehicles to another mini van, and rode the last two hours to Makurdi. She hummed along to a blasting soundtrack of pop gospel music. She finally arrived home at 1:30 a.m.

The exhausting, cramped and boring 15-hour road trip is normal for her. This time she traveled to Lagos on Friday and returned on Monday, spending barely more time in the city than she did en route. She returned with only as much as she could carry. But economically, it makes perfect sense. The bus was her primary expense. It cost 5,000-7,000 naira ($25-35) each way, and she sold each of her perfumes and jeans with a 5,000 naira markup. After selling three items she was already in the clear.

“Goods get really expensive the further you get away from the main port of entry in developing countries,” Startz affirmed.

Benue is known as the breadbasket of Nigeria. Agriculture dominates the local economy. The state is famous for pounded yam, a labor-intensive starch dish. Caroline lives in Makurdi, the capitol, and studies feminist literature at Benue State University. The city has a population under 1 million. With wide streets and sidewalks, it has a completely different pace than Lagos.

December is Harmattan season, when winds blow sand southward from the Sahara desert. Harmattan is stronger in the middle belt than in Lagos; the arid air squeezes skin and pricks eyelids. Red dust coats everything, including sinuses. It is common to come down with allergies or a cold. “Catarrh don catch you,” means “you’ve caught a cold.” Catarrh was a word I hadn’t heard before but it means exactly what it describes, “excessive discharge or buildup of mucus in the nose or throat, associated with inflammation of the mucous membrane.” It comes from the Greek katarrhein “to flow down.”

The dust sullies cars, shoes and clothes but Caroline still dressed in her best. “Just because it’s dusty you think we should not look nice?” She asked.

Her fly, faux fashion is symbolic of a generally performative public culture here. Her clothes screamed swagger, but upon closer inspection were flimsy. For all of her pristine presentation, she lived in a single room home with her two younger brothers. Most Nigerians are impoverished, and most are dealing with serious stress but they still look nice and laugh on top of their troubles. There was nothing inauthentic about the contradiction. She was comfortable with herself, inviting customers into her home to shop.

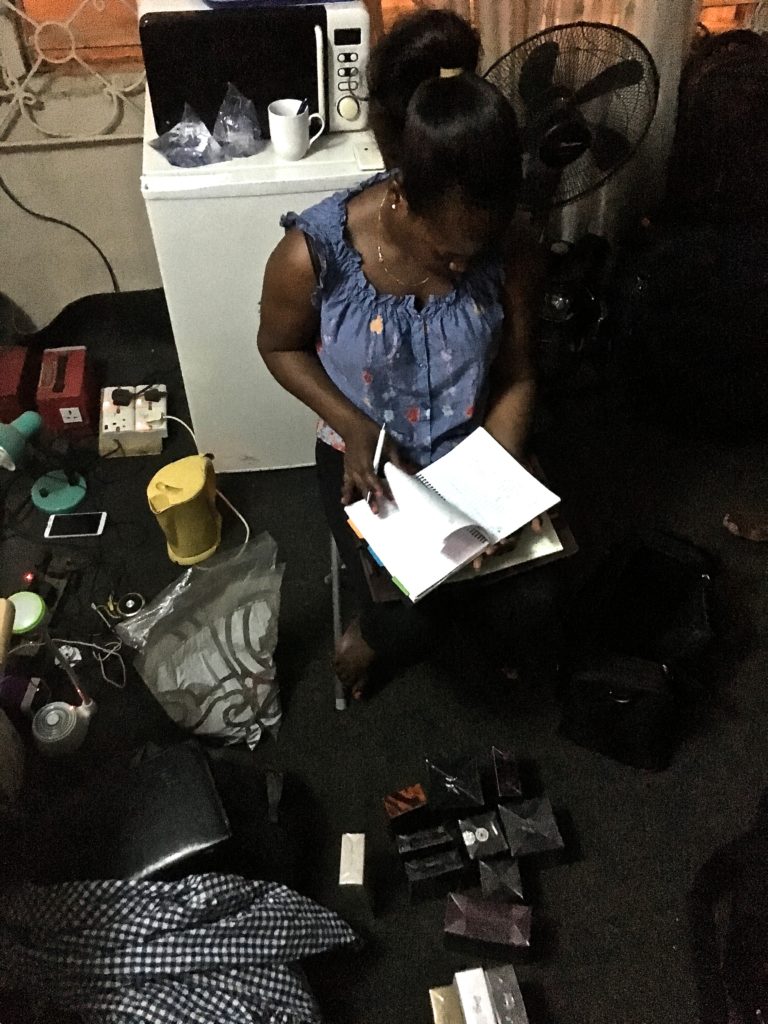

She kept her goods carefully packed away in suitcases. In a handwritten inventory, she noted her stock and the prices. She wrote down every transaction so she could reference what each customer bought and how much they paid after haggling. When a client came she would unpack the goods that suited their needs. One night she carefully unfurled dresses across her bed for a man looking for a birthday gift for his girlfriend.

Most of her clients were friends and friends of friends. She calls some regulars when she returns with fresh stock, and sometimes they send her to Lagos with their orders.

She hoped to open a shop once she graduated from university so she could expand her clientele. But for now she remained firmly in the informal realm.

As an independent entrepreneurial trader, she is part of an enormous subset of the Nigerian economy. “It’s very informal but it’s very, very huge,” Anyanwu said, “a lot of people are involved in that.”

The concept of informality is widely used to describe the economic activities of people like Caroline. But given the scale of it, Abimbola thinks it is almost an incongruous distinction. “Sometimes Nigeria and a whole chunk of West Africa makes me think we have the formal-informal thing backwards. It seems the natural state of things is informality… most economic activities are not in the formal sector with a salaried person’s job.”

But while enormous, it is almost impossible to track or tally these economic activities, because there is nothing tangible or registered. “The problem Nigeria is having now is the challenge of data. There’s so much you can’t lay your hands on,” Anyanwu said. The National Statistics Bureau is still trying to set up its state offices. “You don’t really know how many people are dying in a day, you don’t really know how many people are giving birth in a day. And if you don’t know this simple thing there’s no way you will be able to know how much people are making in a day and how much they are losing in a day.”

Caroline had good reason to keep her trade under the radar. Her small-scale business earned her income without costing taxes. “It takes you a lot to register a company.” Anyanwu said, “its expensive.” He listed the enormous startup costs of paying two years in advance to rent a shop, then navigating the regulatory bureaucracy with its myriad fees. The World Bank ranks Nigeria 169 out of 189 countries for “ease of doing business.”[2]

On the other hand, because she sold from home and mostly to friends she was often pressured to sell on credit. That week the first two clients who called asked if they could pay later. She was already owed 100,000 naira ($500) from clients.

Caroline had not been able to devote her full attention to her business while she was in school. But with her graduation imminent, she was looking to grow.

Her first attempt to expand her business was a Christmas trip to Otukpo. The former president of the senate, a notorious political big man, David Mark, was from the town. His spacious home was a glittering wonderland of Christmas lights. Not far from the mansion was a public arena where he sponsored an annual basketball tournament. Masquerades and carnivals were also on the holiday docket. Caroline trekked to Otukpo and back two days before Christmas to book a hotel room. She was sure all the inns would be overflowing for the festivities.

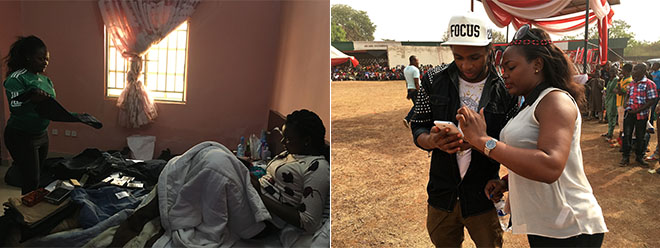

She had high hopes and brought all of her goods with her. The load was expansive so she hired a taxi to drive her to town. Inside her hotel she carefully unpacked the jeans, shoes, shirts, and perfumes and arranged them in the closet. When she opened the door, the fresh scent of new pleather wafted out.

Then she set off to town to meet with friends. Her plan was to tell her friends and acquaintances about her goods and bring them back to the hotel to shop.

At the “Little Miss Otukpo” children’s carnival, pre-teen girls in matching red skirts competed in a miniature beauty pageant. The attendees were even more fashionable, as if the competition was echoed in the stands. Little girls wore frilly dresses and tottered on spindly legs in impossible plastic wedges. Teenagers wore the flashy street style Caroline peddled: bright polyester jumpsuits, oversized shades. She approached one particularly curated young man. He wore a Versace t-shirt, studded jean over shirt, and a baseball hat that said FOCUS. She had met him at an event years before and thought he might have stylish friends who wanted what she sold. They exchanged numbers.

But her friends had already spent all their money arriving in style for Christmas. The tumbling price of oil had rippled across the Nigerian economy, touching formal and informal providers and their many dependents. The civil servants among her customers had not been paid in December.

After three days she had not made a single sale. As her first attempt to sell outside the home, it looked like a dismal failure.

She was disappointed, but she has a steady cheer to her, and she concluded that she had at least enjoyed the holiday. “Business is always risky,” she said.

But she was worried about what she would do with all of her merchandise. She didn’t want to spend the money on a private taxi back home again. And it was an unwieldy mass for public transport. She had several suitcases, her stockpile from numerous trips to Lagos.

***

On her second to last night in Otukpo, she went for drinks at one of the nicer hotels in the center of town. She posted a photo on Facebook and a friend commented that he was lodged at the same hotel.

They met and she told him about her goods. A regional manager for Fidelity Bank, he said he had recently returned from the UK, so he didn’t need to shop. But she brought over some things for his friends to peruse. One was an engineer, another a chief of naval staff.

“They were big guys,” she said.

She sold them one pair of sandals and two perfumes and made 100,000 naira ($500) in one go. This was the kind of windfall she had expected for Christmas.

Her luck didn’t end there. Her friend offered to drive her back to Makurdi in his “very serious jeep.” There, he brought her to a party. He introduced her to another friend, the son of Benue’s deputy governor who was constructing a hotel. He hit it off with Caroline, and offered her a boutique space in the lobby.

This was a potential jackpot. “The fact that he’s into politics—his dad is deputy governor and he’s the one that runs most of his dads affairs—so I‘m sure he’ll have good sales because people will be wanting to get favors from him. People will want to come stay there to make him feel good so they can get contracts from him,” she said.

Economists describe Caroline’s clientele as a “kinship network,” academic jargon for friends of friends. Prayers, hopes and business plans center on the serendipitous connection with this sort of higher class extended network.

The politician’s son already planned a small shop to sell business essentials: perfume and liquor. He hoped Caroline could supply the odorous commodity.

She was enticed by the offer, and they planned to meet to hammer out the details. “The caliber of people that will be coming in is the kind I’m looking out for,” she said. “That’s cool, that’s really cool.”

[1] http://shelbygrossman.com/on-going-field-projects/

[2] http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings