TAIPEI — Fifty-year-old Ah-wen (played by Wu Shih-wei), the protagonist of Party Theatre Group’s (Tong Dang Ju Tuan) play “Father Mother”—re-staged during this year’s Taipei Arts Festival at the Taipei Performing Arts Center—is, above all, mediocre. He is divorced and estranged from his eldest son, bullishly opinionated with family but meek before strangers, politically dispassionate and emotionally avoidant. His splayed fingers often rub against the sides of his shapeless dad jeans, palms lifting with his eyebrows as though about to gesticulate but lacking the courage to commit.

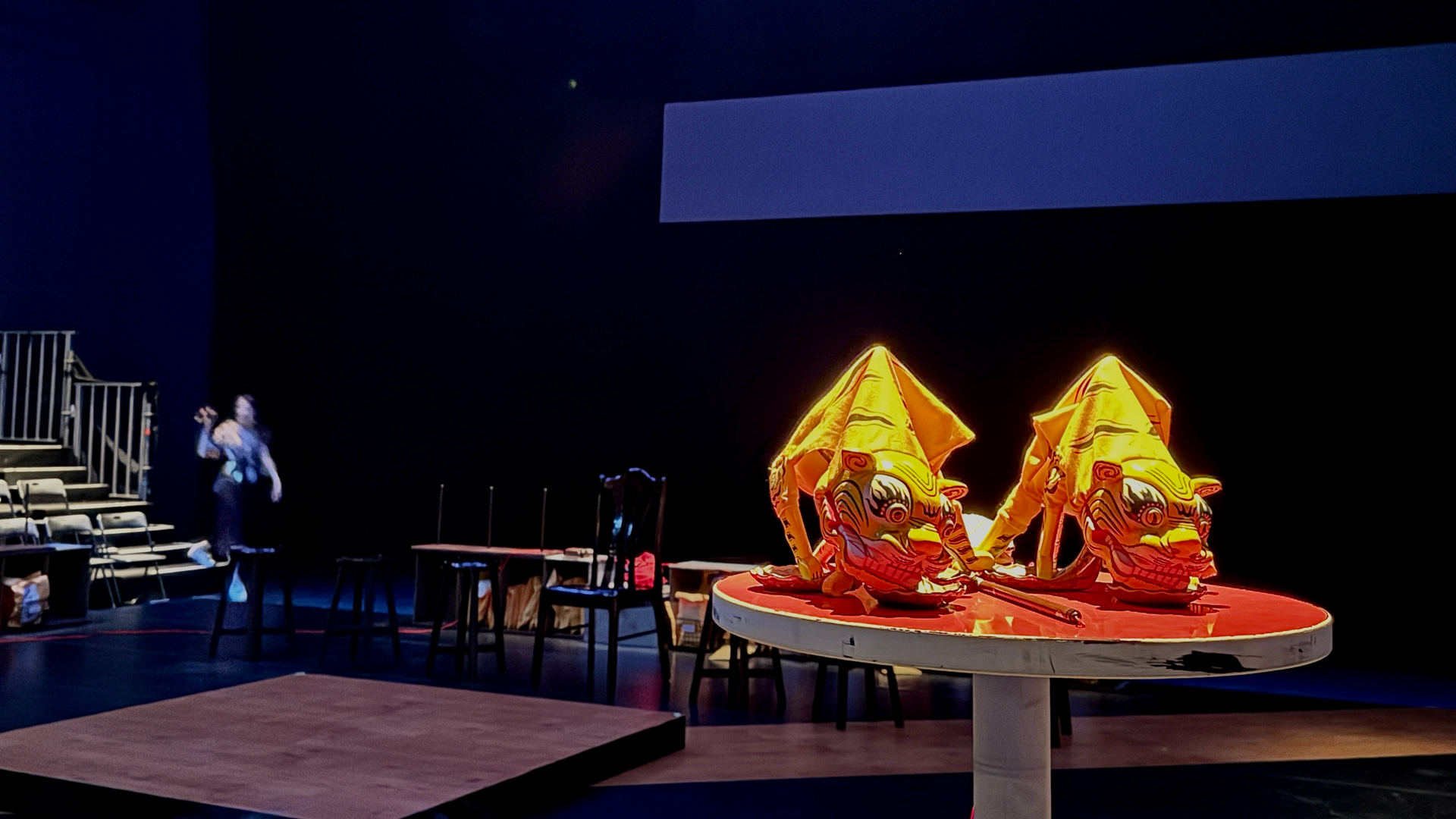

But perhaps it’s because of how familiar he is—this archetypical wallflower of a middle-aged Taiwanese man—that we root for him. In the opening scene, Ah-wen bursts into his adoptive father’s funeral with a photo in hand: a man and a woman, backs straight and shoulders pulled back, cradling baby Ah-wen, recognizable by his birthmark. Beside them is a bar table with two tiger puppets, identical except that one’s pupils are painted as crescent moons, the other’s as suns. Bouncing across the stage—a simple raised platform, four scattered stools, surrounded on four sides by low-floor storage cabinets stuffed with props and sealed manila envelopes—he grips each of his relatives’ shoulders and asks if the man in the photograph is his birth father.

An uncle takes the photo, rips it and storms off with the scraps: “You’ll regret wanting to know!”

“Well, it’s a good thing I took a photo of the photo,” Ah-wen says, holding his iPhone in cheeky defiance.

Thus begins Ah-wen’s journey across Taiwan and time, through humor and tears, in search of the man in the photograph. Through dreamlike flashbacks dating from the 1930s to 1980s, as narrated by acquaintances and relatives who occasionally break the fourth wall and interact with the present-day characters, the man in the photo, named Mao-tsai (Wei Yi-cheng), comes alive. He is an actor in glove puppet theatre (budaixi or bodehi), a traditional Taiwanese performance art in which puppeteers operate and voice brightly colored hand dolls. “I’ve always been attracted to the music of budaixi. My father must be the reason why,” Ah-wen exclaims to Ah-kai (Jasper Hsu), his recalcitrant 20-something-year-old son. Ah-kai, with a backpack slung over one shoulder, rainbow flag streaming from one of the straps, twiddles his thumbs on his phone and pretends to care, a generation removed from this history.

Indeed, the weight of history grounds much of the play’s first half, which traces the rise and fall of glove puppetry as a metaphor for Taiwanese history in the 20th century, while Mao-tsai ages through Japanese colonization (1895-1945) and the White Terror, when the Kuomintang (KMT) government imposed authoritarian rule from 1947 to 1987. As Taiwan passed from regime to regime, its people consistently suffered abuses to their psyches and human rights. “Who are we,” Mao-tsai asks, “if we are Japanese one day and become Chinese the next?” Betrayed by the KMT regime’s promise of glory and consequent injury, Mao-tsai becomes a political dissident, allegedly distributing democracy propaganda. After his sister-in-law reports him to the authorities for fear her family would be implicated by association, Mao-tsai is executed for treason.

But this, we learn, is not the regret Ah-wen’s uncle foreshadowed. Stories about the White Terror are not uncommon across Taiwanese media and culture, in a country still lurching toward transitional justice for the thousands executed, tortured or disappeared for their political expression like Mao-tsai. Halfway through the play, Ah-wen goes to Taiwan’s National Archives to cross-reference the stories he has collected about the shadowy Mao-tsai—only to learn that the latter’s legal name and execution date do not match.

A tense silence falls over the stage.

Mao-tsai is not his father but the late lover of Mi-fen (Lin Tzu-heng): Ah-wen’s true birth parent, an estranged member of Ah-wen’s adoptive family and the transgender woman holding Ah-wen in the opening photo.

When Ah-wen, mouth agape, later meets Mi-fen in the gay bar she has opened in contemporary Taipei, the audience holds its breath, rooting for his usually restrained emotions to burst through once more.

* * *

The White Terror and LGBTQ+ rights are not often mentioned in the same conversation. During the former, fear was inculcated across all society as close family and friends betrayed one another, often over alleged crimes of treason or political intrigue, in crises of self-preservation. In “Father Mother,” Mao-tsai’s sister-in-law—bucket hat hiding all but the depth of her shame—nearly falls out of her wheelchair trying to kowtow to Ah-wen. Her voice falters as she devolves into apologies, her hands shaking and head hung low: “Mao-tsai, why did you need to be involved with politics?”

At a White Terror commemoration event earlier this year, a political activist told me that the country’s authoritarian past has shaped the mentality of many Taiwanese people, even today. They believe, “if I am quiet, if I do not try to rock the boat, the government will protect me.” Indeed, Taipei’s National Human Rights Museum notes that the White Terror “cast a profound impact on people being silent and apathetic toward political and social issues.” Ah-wen takes the sister-in-law’s hand amid her apologies, perhaps in disbelief of Mao-tsai’s identity, or lucid self-awareness that he is like her: fearful of politics, avoidant of modernity, a status quo preservationist at heart.

Through the actors’ measured silences and tense gestures, “Father Mother” avoids preaching about the White Terror and instead contemplates how our bodies keep score of historical trauma. For multiple generations, fear and mistrust has bred a culture in which to stand out was unthinkable.

It’s through the context of contemporary LGBTQ+ issues that the play reveals how deeply the scars from the White Terror have penetrated Ah-wen’s—and Taiwanese society’s—psyche. Between flashbacks to Mao-tsai’s history, Ah-wen encounters a bilingual street canvasser with a rainbow bandana tied around his forehead. It is 2018, before same-sex marriage was legalized in Taiwan, and the country is preparing to vote in a public referendum to express support or opposition.

Here, Ah-wen’s homophobia spills out without restraint. He is humorously afraid to even utter the word “gay”; on the other hand, he is damningly dismissive of the canvasser, accusing him of bringing the end of bloodlines and therefore society—familiar accusations to any LGBTQ+ activist at that time.

Little does the protagonist know, however, that his son Ah-kai is on the other side of the stage, pro-LGBTQ+ billboards strung over the front and back of his body. Head down, Ah-kai walks over, gently helps his fellow canvasser relocate and, just as Ah-wen begins to stutter Ah-kai’s name, sternly shouts back, “Sir, could you please stop messing around?”

Actors Wu and Hsu portray the father-son relationship with devastating accuracy. Ah-kai’s adolescent flippancy and swaggering gait in earlier scenes molt to reveal a blank expression here, as though he has given up on concealing his disappointment. Ah-kai is his father’s foil: queer, eager to chart his own career path in politics and resenting Ah-wen’s imposition of stability on him. Later in the play, after the public vote in favor of same-sex marriage fails to win a majority, Ah-kai slinks back home for the first time since the public encounter with his father. “You voted against us in the referendum, right?” he assumes of Ah-wen. The resignation in his voice is familiar to every queer person conditioned to expect the worse who still asks out of a persistent hope that their family will come around.

Wu, on the other hand, thrives in the nuance of his stammering affectations. In the anxious cadence with which Ah-wen tries to talk Ah-kai out of a political career or the longing voicemail he leaves for Ah-kai to come back home, Wu reminds us that Ah-wen is a father. He is a flawed father, reminded of deviance’s devastating consequence during the White Terror and wanting to do everything he can to protect his child—except empathize.

When a hunched-over Mi-fen gloriously saunters into the rainbow disco-refracted Paradise (An Le Yuan)—the bar she named after Mao-tsai’s puppet theatre troupe—while reprimanding her barkeeps to tidy up the space, something in the theatre shifts. We know before Ah-wen or Ah-kai who she is, dressed in a red and black speckled blouse and sheer, ankle-length skirt, her wrist limply resting on air as if to orchestrate the next act. Indeed, the actor Lin commands the second act as he narrates Mi-fen and Mao-tsai’s story and threads together Taiwan’s two eras, represented by the White Terror and modern LGBTQ+ activism.

The connection lives in Mi-fen’s very identity: a transgender political dissident and survivor of the White Terror. Ah-kai speaks for us in the audience when he exclaims, “O.M.G! Grandpa’s a diva! He was way ahead of his times!” Ah-kai’s excitement upon meeting Mi-fen is infectious: such scenes of intergenerational exchange between queer elders and youth are rarely represented.

Flashbacks tell the backstory. Assigned male at birth, Mi-fen dutifully marries a woman who gives birth to Ah-wen. After coming out as a transgender woman, she not only survives estrangement from her birth family but also imprisonment when she is captured by the authorities with Mao-tsai. Her gender identity adds color to her alibi as a mentally ill mute.

During these flashbacks, Mi-fen is not yet the heel-wearing manager of gay bars. She tucks her chin meekly into her neck whenever she speaks, puppy eyes glowing upward with an innocence that is unrecognizable in Mi-fen today. But this shifts in the play’s climax. Mi-fen meets Mao-tsai for the final time in his prison cell on Green Island, formerly Taiwan’s Guantanamo Bay. A spotlight is cast on the two lovers and grey smoke spews above as Mi-fen asks, simply: Ni hao ma? Are you well?

No more words are exchanged. Separated by an imagined prison gate, the two lovers start laughing uncontrollably. They laugh and laugh and reach for one another’s hands because, indeed, what a ridiculous question to ask someone on death row. In a second, the entire stage will turn red, Mao-tsai will collapse and tears will run down my face even though we all knew this moment would come, but behind the laughter is Mao-tsai’s life motto and final words to Mi-fen: “I would rather die than be manipulated like a puppet. I will die for my identity with no regrets, so please live bravely with yours.”

At the heart of “Father Mother” is the pursuit of freedom. Of course, each character’s goal is different. Mi-fen seeks to live boldly as a transgender woman. Mao-tsai seeks to think for himself without a Japanese or authoritarian White Terror regime telling him who he is.

Ah-kai seeks to marry the person of his choice and live unburdened by his parents’ expectations. When Ah-wen realizes he was not abandoned by his birth parents—that Mi-fen sent him to her family right before she was imprisoned to protect him—even he begins to free himself from the fears and hesitations that underlie his conservative mindset. He gradually comes to accept Ah-kai’s sexuality, though at the end, he still coughs past the words “gay” and “boyfriend.” Across a fractured history of colonial and authoritarian repression and the outburst of pluralism and democratic values that followed not long after, Taiwanese people have always been searching for themselves.

Freedom can be realized if we properly reckon with the past: the play’s core hope seems very idealistic when I write down. Indeed, Ah-wen’s transformations happen quite quickly at the end, and I wonder if the play’s events would truly be enough to liberate the mind of a character like Ah-wen, who carries 50 years of intergenerational trauma. Would Ah-kai really be able to forgive his father so easily?

Perhaps not. But as Ah-wen journeys to meet each of Mao-tsai’s acquaintances, they each leave Ah-wen with apologies or final words for the late puppeteer, whether for reporting him to the authorities or not stepping up when Mao-tsai was beaten by Japanese police officers. After Ah-wen collects these regrets, he then has the choice to sprint out of Paradise Bar upon seeing Mi-fen for the first time, captive to his internalized homophobia. But with a little help from his son—who is ecstatic to learn that his grandparent is queer and transgender—Ah-wen stays and shares with Mi-fen his abandonment issues and desire to hold together this family. Cycles of trauma are broken as the three characters tearfully hug and learn to accept each other, their identities forming still.

“Father Mother” impressively wheels through these massive questions of history and identity through one family’s emotional journey. But as spectacular—if not more—is the two-hour play’s creative casting and staging. Only six male actors play a total of 36 different roles, each skillfully adopting different personas, genders and accents and delineating the different periods through which the play traverses. The Party Theatre Group’s director, Chiu An-chen, admits that this started as a financial constraint, but with the recognizable return of each actor is the suggestion that the past haunts each of us in inexplicable ways. Only when we support one another can we bear the weight of time.

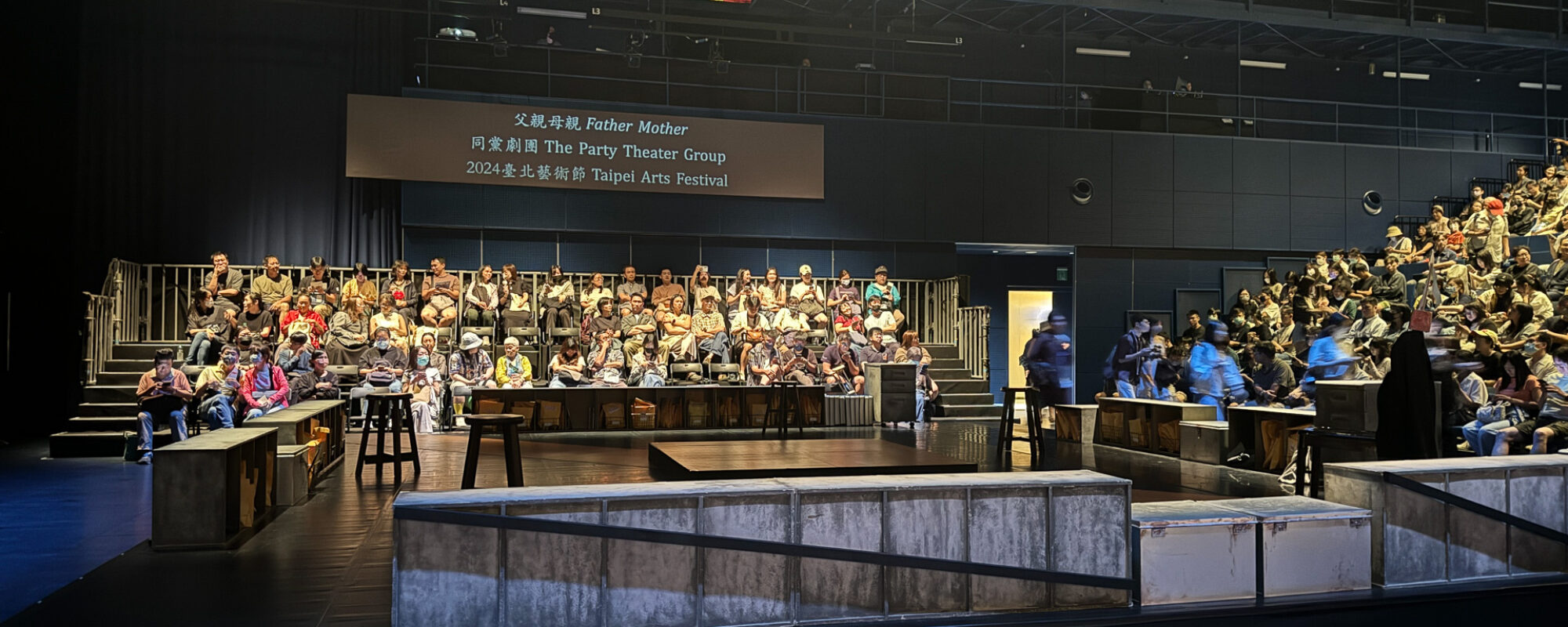

Top photo: The stage of “Father Mother” before the play begins