TAIPEI — Troye Sivan had me thinking about peppers at my first party here.

It was the Third Anniversary Gala of Queer Trash Taiwan (酷兒垃圾). Strings of red chili peppers hung off exposed pipes from the stickered DJ booth in the back to the open entrance in front. Over a mess of wires looping between five DJ turntables, a disco ball refracted neon green beams from the LED sign on the DJ’s left, QUEER TRASH displayed in grungy collage print. As Dua Lipa blasted from the two speakers flanking the DJ booth, I wove through a diversity of bodies, races, genders and levels of skin exposure reminiscent of Bushwick, Brooklyn on a Saturday night—except this self-proclaimed “trash party for queer people” was hosted in the near 100 percent humidity of Taipei in October.

Too swept up in the unabashed dancing and kissing around me, I didn’t notice the peppers until later at night. When the party’s first lull trailed like sweat down skin, I saw the tabasco-red clusters tiptoe on a partygoer’s head—delicately, as though not to overstep the fine line between camp and kitsch. Was this an inside joke between the organizers? Did they just buy random decor on Shopee, Taiwan’s Amazon equivalent? Or are they playing with words, inciting us partygoers to be more 辣— a word that literally means “spicy” but figuratively evokes sexy and unburdened confidence?

That word was the night’s refrain. Earlier, over wine and repeated scoops of peach ice cream, I exchanged music video recommendations with three new friends in their shared apartment: an American and two Taiwanese 20-something-year-olds. Once the remote reached his hands, one queer Taiwanese roommate projected the Australian singer Troye Sivan’s recent videos onto the wall opposite the couch. We bore witness to the sex-addled, homoerotic chants of “Rush” and the forlorn drag sensuality of “One of Your Girls” in captivated silence. Breaking through the trance was that familiar phrase, repeated over and again by the two Taiwanese roommates, as had happened the four other times I had seen these videos in bars and stores across Taipei last month:

好辣耶.

So spicy. “He’s finally moving past his gay twink era and becoming queer,” the same roommate proclaimed. He got up midway through the final video to get dressed for the party, reemerging every few moments to adjust his silver corset, thinly laced in the back. We all agreed that his outfit was exceedingly 辣. “I really like this version of Troye.”

A few hours later, when the first synths of Charli XCX’s “1999” (featuring Sivan) twinkled from the speakers and broke the dancefloor’s lull, and the crowd exploded in pitch and aerial height before I even knew what song it was, my eyes were still locked on those peppers. Part of me wondered in those initial hazy seconds if I was 辣 enough, almost like an aesthetic prerequisite of queerness.

Hustled back into the crowd’s libertine pulse and joy, my self-awareness quickly diffused. As I’ve begun to acquaint myself with LGBTQ+ folks across Taiwan, I initially set out with a curiosity about what it means to be queer here. In that process, I’ve come face-to-face with something even more expansive: a mounting desire to explore and express one’s identity, whether camp or kitsch, through labels like queer or aesthetics like 辣. In the backdrop of an island nation solidifying its sense of self against geopolitical tension and a palimpsest-like history of diverse influences, I, too, am finding comfort in this collective process of self-discovery.

Across Taipei’s pockmarked concrete and lush greenery, I’m identified more by my speech than my face. When I order food over the soft sizzle of a streetside hot plate, I am frequently asked where I am from, tongue still hungover from a year of graduate school in Beijing. I’ve become fluent in explaining my mangled accent—that of an American-born-and-raised son of immigrants from Fuzhou, China—but no more comfortable with what it means.

After all, language is a conduit of sovereignty: Taiwanese people distinguish their Mandarin Chinese as 國語—literally, “nation’s language”—from the mainland’s 普通話—or “common language,” a direct evocation of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s desire for a standardized script and speech. While variations of Mandarin also exist in mainland China, the two sides of the Strait experienced 38 years of isolation, from 1949 when the Kuomintang (KMT) fled as refugees from the CCP until 1987 when the KMT’s martial law was lifted. In between, only war brought people across the waters, and the two languages became ships passing in the night.

A Taiwanese friend made some simple discrepancies apparent to me before I had arrived: daily banalities like “text message,” “hotel” or “trash.” Yet even when I know the right word, my tongue still stutters like a bike on loose Taipei sidewalk tiles.

Picking up on that, a Taiwanese-American friend who has lived in Taiwan for more than 10 years whispered at an outdoor gay bar: “Don’t go around telling people you’re Chinese-American.” Puffs of cigarette smoke obscured whether it was meant to be a joke or reality. Before I could ask, he disappeared into a crowd of tank-topped gay men—but I also didn’t need to. Since President Tsai Ing-wen was elected in 2016, China has repeatedly rejected diplomatic talks with Taiwan, replacing them with simulated attacks and combat exercises. Against the backdrop of this aggression, I was already self-conscious about how much or to whom an accent could sound like a drill whistle or missile engine.

However, another Taiwanese friend—self-described as the “non-mainstream of the non-mainstream of gay men and therefore queer”—reassured me on this point. At a braised pork over rice (滷肉飯) stall, huddled over plastic stools and wobbly metal tables that sprawl onto the sidewalk, my friend’s soft and high-pitched voice competed against a middle-aged woman’s as she admonished her grandchild for wailing right next to me. (That softness, he said, is part of his queer identity, and stands in contrast to the stereotypical, muscular, masculine gay man here.) He explained that while partly linked to China’s denial of Taiwan’s sovereignty, people here likely ask where I am from because they, too, are searching for who they are in their own right. Against a history of occupation—by the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, two Chinese dynasties, 50 years of Japanese colonization and the KMT’s authoritarian rule—Taiwanese people are finally in a position to define for themselves who the “new Taiwanese” is, as first proclaimed by former President Lee Teng-hui in 1994.

Ann-jiun AJ Wang (王安頤) echoed the possibilities that have opened up in the last few decades. Sitting across from them in their home office, I was taken aback by how approachable they were: casually dressed in a gray v-neck shirt and workout shorts, clutching one of two heart-shaped pillows on their couch throughout our conversation. Their Instagram is an archive of buzz and pixie cuts dyed in various colors, over-the-shoulder smolders and poses that shift from soft femme drapery to frontal power stances. Before meeting them in person, I felt an overwhelming confidence in the limitless potential of who they could be.

Wang is the multihyphenate behind LEZS, an independent LGBTQ+ and lesbian-focused lifestyle magazine in print from 2008 until 2019, as well as LEZSMEETING (女人國), an Asia-wide party brand for women and femmes that celebrated its 20th anniversary during this past October’s Taipei Pride. When I asked them for their gender and sexual identities, they clarified if I meant their current one. In their teenage years, when journalists would still secretly surveil gay and lesbian bars, they found comfort and safety within bisexuality as a category. But as the media and political environments improved year by year, it had become harder for them to deny their true lesbian self.

After tussling and turning between different micro-labels in the lesbian community—from leaving their hair long to be more effeminate to buying baggier clothes as a tomboy, all in search of what a potential partner might like—Wang feels like their sexual identity paved the path for their gender expression. Now in their early 40s, they’ve found comfort in identifying as nonbinary (非二元). “Without a gender framework, you can more naturally express and find who you are,” they said. But across the long process that a nation, imagined community or single person may take to cement its identity, “labels still set the room for me to explore who I am and give me a sense of security,” Wang told me.

“Happiness isn’t a mathematical or legal idea, but it used to feel that way,” they added. In addition to the hangover of history, they pointed to a familiar Han Chinese culture “where the pathway to success used to feel very determined. But now we have the chance to find the one and only (獨一無二) versions of ourselves, to directly face the pain and joy of being true to ourselves.” For both of us, those pains included hard lessons learned from toxic relationships, as we recognized versions of ourselves in the other’s experiences.

As we continued to share stories and laughs in the pastel comfort of Wang’s office, I felt increasingly at ease. Not only in that moment but also in the necessary and assuring realization that I am only starting to recalibrate my Chinese-Americanness, my queerness as a cis gay/queer man, my personality in this second language and entirely new context.

And a mellow but assertive tone, Wang affirmed: “It’s okay to take the time and support we need.”

Along Fude Street Alleyway 221 (福德街221巷) on the southeastern fringes of Xinyi District, the bustle of Taipei’s business center opens to barber shops with low-hanging canopies and empty produce stalls that fade into the streetside greenery. Around the first turn of the winding road, the only sound I could hear was the echo of a karaoke mic, Taiwanese Hokkien (台語) lyrics radiating from a mint-green steel shack. I peeked in: box TV, beers scattered across a few circular banquet tables and middle-aged women all on their feet, swaying with an ever-slight bounce.

But just a few steps more into the green mountains, the karaoke began to blend with a house beat. In late October, a self-described “music, art, and queer festival” known as Spectrum Formosus (光譜音樂) returned to Taipei for the first time in four years. Held next to an abandoned temple on Tiger Mountain, the open-air electronic music festival aimed to “find our most liberated selves in a universe free of binaries” through a six-hour roster of local house/techno DJs and interactive performances: a panel on homonationalism, a talkback with a young dancer, a drag queen comedy hour and even a candle-making workshop. Inside the temple, where a red glow bathed recessed columns and faint wall paintings, I heard a participant complimenting an organizer for the “queer and avant-garde” choices, pushing the boundaries of a music festival’s purpose and definition. I came to this festival curious about this brand of queerness.

I found an answer in one of this year’s performers: Lin Pinxi (林品希), a 14-year-old dancer and performer based in Pingtung on Taiwan’s Southern coast. During the talkback with his mother, Lin sat in his chair with his back straight, shoulder-length hair neatly swept behind his ears, hands folded over his crossed legs. Assigned male at birth (AMAB), Lin has often been singled out in his advanced dance classes. Past classmates would call him a “sissy” (娘娘腔) for his love of makeup and dance, and their parents would offer unsolicited advice when they met his mother.

Lin is sometimes referred to as a Rose Boy (玫瑰少年), a gendered term coined by the Taiwan Gender Equity Education Association to respect young AMAB kids with feminine characteristics. The term entered popular discourse in the early 2000s after the Yeh Yung-chih case, in which another Pingtung-based boy was aggressively bullied for his gender nonconformity and later found unconscious in his high school bathroom. While the Justice Ministry claimed his death was the result of a medical condition, Yeh’s mother and gender activists pushed for greater recognition of gender and sexual minorities—and ultimately helped establish the Gender Equity Education Act in 2004.

I wondered if the Rose Boy identity and that legacy weigh on Lin—in a nation where gender-based discrimination and patriarchal values persist. Sitting in front of a crowd of 20 or so attendees, fading in and out with the outdoor DJ sets, Lin lost his train of thought. He was talking about the steps to “做自己” (“be yourself”) and after explaining that the first one is to identify who you truly are, he looked up at the ceiling in search of more words. His mom, Ye Yijing, saved the silence and described her parenting approach. Her goal, she said, is to give her child room to explore gender and sexuality at his own pace.

The panel’s host, DJ Gemnital, jumped in to say that this was a queer festival, or one that aimed to celebrate a range of genderfluid possibilities. They then turned to Lin: “So the next time someone calls you a sissy, you should flip your hair, look them back in the eye and say: ‘Yes bitch, I am.’”

The crowd snapped and hollered over the unapologetic ad-lib, cheering Lin on in the full life ahead of him. To be 14 years old and talking about how to be yourself in front of a crowd of well-dressed, genderfluid adults seems like an impossible task to me even today. In between moments when we all became silhouettes against a smoke machine, I spent the rest of the festival shyly peeking at others’ fashion, admiring a tender periwinkle wrap-top here, the dark grunge of a straight-legged, maroon leather pant there—wondering if I could pull any of it off.

Here, to be queer felt like a statement, a declaration that I am here to push the envelope of what is acceptable—and that felt cool. The term “queer” in Sinophone contexts (translated as 酷兒) doesn’t have the same reclaimed nature as it does in the Anglophone world; the two characters literally translate to “cool” and can be traced back to radical sex-positive scholars and activists from the 1990s. Given these elite academic beginnings, my friends told me that if I asked people at Pride (of any generation, any gender) about the term, I’d probably be received with confusion.

For some, queerness is just an aesthetic or personal brand, defined in part by its negative—not the stereotypical cis gay man; not the patriarchy—as much by the coolness of the words’ literal meaning. But for others, queer seems to point at an intentionally undefined expanse—a spirit of not only discarding broken systems but finding new possibilities in their stead.

On May 17, 2019, when Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan approved same-sex marriage, a rainbow appeared in the wake of torrential rain. When I ask queer folks about that moment, there is a collective recognition of its importance; They talk about the tears of joy and relief that flooded the court and streets as the multi-year, coalitional campaign successfully and finally came to an end.

In the same breath, at least among the major organizations involved in those campaigns, they also recognize that the rainbow does not end at marriage equality. Indeed, mainstream LGBTQ+ organizations such as Taiwan Tongzhi LGBTQ+ Hotline Association (Hotline) and Taiwan Alliance to Promote Civil Partnership Rights (TAPCPR) have since turned their attention to transgender rights and other forms of gender diversity across the island. Even as the fight for comprehensive marriage equality continues, a newfound urgency sought to address the medical, legal and workplace discrimination faced by a burgeoning transgender community. It just so happened that quietly, right before the marriage equality bill was signed into practice, the grassroots organization Taiwan Nonbinary Queer Sluts (台灣非二元酷兒浪子) was founded.

“If we were established even a few days later, I don’t think we would have the clout or attention we have now,” Yu Tu (玉吐), one of the founding members told me. But with the rush of advocacy and public education on gender-diverse communities, Nonbinary Queer Sluts became a critical resource for mainstream organizations to learn from nonbinary and trans folks’ lived experiences. Before 2019, a Google Search for “非二元”—the Chinese translation of “nonbinary”—would turn up very few, if any, results. After 2019, with the organization’s educational events and resources, the term began to enter Taiwanese discourse. That echoed the timeline on which Wang and other nonbinary folks encountered the term.

I was introduced to the organization at its 2023 Survey Publication Event, hosted a few days before Taipei Pride at Fembooks, the first feminist bookstore in the Chinese-speaking world. Emceeing the event was Yu Tu, whose fiery humor and statement thick-rimmed glasses were balanced by the level coolness and hoodie casualness of Daniel Yo-Ling (有靈): a Taiwanese-American researcher of local LGBTQ+ issues, Nonbinary Queer Sluts member and the survey’s designer.

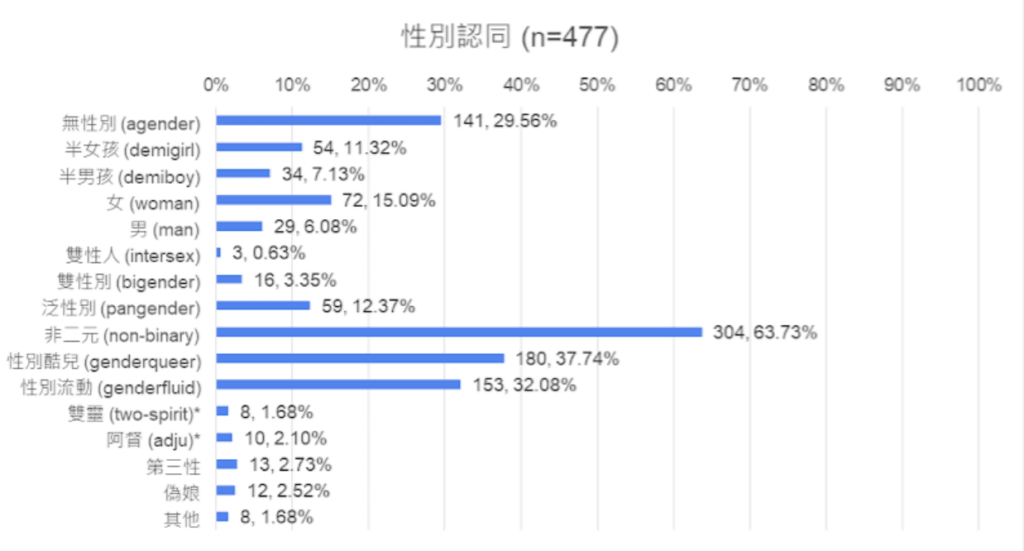

In front of about 50 attendees, Yo-Ling eloquently presented the results of the first-ever survey to focus on Taiwan’s nonbinary population, which collected 477 responses between July and September 2023. In addition to questions on general demographics and gender identity, the survey also asked for respondents’ attitudes toward various legal debates, namely the inclusion of a third gender option on official documents and the necessity of gender affirmation surgery for a legal gender change.

What initially struck me was the diversity embedded in the survey’s design. For example, 17 different gender identity labels were offered in a multi-select, multiple-choice question about gender identity. Even still, some respondents chose the “other” option. While 50 percent of respondents supported a third-gender option of “Nonbinary (非二元),” the other 50 percent was scattered across a litany of other choices, including calls for the total abolition of gender identity on legal documentation.

Yo-Ling explained that nonbinary as a term has exploded in use in the last two years. Collectives of nonbinary folks have hosted social gatherings across Taipei. Yo-Ling has also been pleasantly surprised to see folks thrive beyond the comfort of nonbinary-centered spaces. At a working group on LGBTQ+ education hosted by Hotline, they recalled that “in a circle of about 30 people, about five introduced themselves as nonbinary. I thought: ‘Wow, there are more nonbinary people here?’”

With visibility comes a hint of normalcy still elusive for nonbinary and trans people. As Yo-Ling described the history of terms used in and around the nonbinary and trans communities, it became apparent to me that some labels were imperfect, devised in the urgent, lonely fumble for identities not yet imagined. The Hokkien term 穿褲的 (tshīng khòo–ê) is sometimes used by butch lesbians and trans men unaware that these other terms (of English origin) and possibilities exist. 第三性 (literally, “third gender”) derogatorily refers to transgender women who do not pass. Yet for those far from the cosmopolitan carnival and diversity of a hub like Taipei, it may be the only identity grounding them.

I wondered how they all melded together—if there truly was a collective beyond the annual music festival or the individual scavenger hunt for identity. Between the respectful differences that Yo-Ling and Yu Tu acknowledged in their views, it was clear that Nonbinary Queer Sluts is built on an inclusive ethos, welcoming anyone who may have felt alone or misunderstood for falling outside of a cis-gendered framework of “man” or “woman.” In the context of legal advocacy led by TAPCPR, nonbinary folks are housed under an even broader umbrella term of “transgender”—another imperfect yet strategically legible way to open the window of non-cis-gendered possibilities. (I’ll return to this subject in future dispatches, as well as much more about Nonbinary Queer Sluts.)

As I reflected on my conversations with activists and public personalities like Yo-Ling, Wang and so many others, a common question emerged: in the construction of a movement—to form a united front on the scale of marriage equality—how does a plus sign (at the end of LGBTQ+) or an asterisk (at the end of trans*) evolve from a symbol to a reality? How do we respect the present utility and usage of these categories while imagining a future rooted in intersectional and collective identities? As I find myself among people giving attention to spectra of gender and sexuality—from HIV/AIDS advocacy to lesbian visibility to trans rights and so much more—I see a network of unique threads reaching for one another, twirling and unwinding in the unending dance to create change.

I later confirmed that the peppers were a playful, frivolous addition.

“Our Sagittarius party with absolutely no decorations was our most popular one, so I don’t think about the decor too deeply anymore,” Sung Zheng Yi said. I met Sung, the nonbinary founder of Queer Trash Taiwan, in the lobby of a 5th-floor hostel in the heart of Ximending, just a few turns away from the famed rainbow sidewalk in Taipei. The streets of Ximending seem to be busy at all times of day; in the afternoon, hordes of tourists swarm beneath the area’s electronic billboards, into jewelry hideouts or the five Nike stores spread across other brands. In the evenings, under the fairy lights behind the historic Red House, mostly cis gay men flock to the gay-centric clubs, outdoor bars and karaoke joints that stretch until morning.

At the Third Anniversary Gala, I first saw Sung in their drag persona Bryonica Brita—named after the brand of drinking water filters to evoke the idea of “filtering out toxic, trashy, masculine, straight men.” Their hot-red gown and matching eye shadow that evening glistened against the neon green light flashing across our skin. But today, they were dressed down in all black, from circular-framed glasses to collared shirt, three or four buttons casually undone. When they referred to their age (40s), I was sincerely shocked; their porcelain skin showed no signs of someone who had hosted a foreign DJ until 5 a.m. that morning.

Inspired by their experiences as a punk artist in Berlin and Taipei, Sung wanted to create a free party where queer kids would not have to worry about cover charges or other financial burdens. This class-based ethos—the root of Sung’s queerness—extends into the party’s design. The doors are wide open, with trash pop music blasting out into the streets and competing with nearby bars. (“Only originals. One of the only remixes I’ll allow is a techno version of ‘My Heart Will Go On.’”) A relatively young-seeming crowd moves in and out of this borderless space at will, including drag queens, who are paid to mingle and get exposure as guests as opposed to just performers.

Sung mentioned that while they aim to be inclusive, there’s often a limit. While queer people across the LGBTQ+ spectrum find one another in a shared love for Madonna, Sung pointed out that femme folks occasionally come to the DJ requesting support from predatory men. This is a familiar struggle for queer party hosts elsewhere. The party’s slogan—“A trash party for queer people / Not a queer party for trash people”—and its norms (posted on social media) are meant to signal safety for queer people, which has been one of Sung’s priorities since the party’s founding, but it’s often easier said than done. But Sung and his chosen family are determined to maintain safety, wading through the undefined waters of “queerness” that many others are charting beside them.

The politics of hosting parties and building movements feels particularly close to that of a nation’s. Just as Taiwanese LGBTQ+ people and activists grapple with an umbrella that can inclusively yet distinctively capture their experiences, the “New Taiwanese” identity first conceived in 1994 is still in a fluid state of definition. Even the concept of national identity in Taiwan differs depending on who you ask, often somewhere in the interstices between citizenship, democracy, culture and territory. But when same-sex marriage passed, these two pursuits of identity—of gender and sexuality, of nation—seemed to converge. Rainbow flags fly not only in the gay-friendly quarters of Ximending but across Taipei, on windows where Taiwan’s flag or banners of “Taiwanese Independence” hang nearby. This nation seems to have found (some) gender-based and sexual rights as part of its own identity.

Waiting for our takeout dinner to arrive at the end of our interview, a Taiwanese transgender woman described her nation’s history to me as “chipped porcelain. When you switch from the wrong to the right side of history in just days, you begin to question if history and identity are yours to decide”—referencing Taiwan’s switch from a Japanese colony to an Allied stronghold at the end of World War II as an example. “And maybe we are still finding our self-confidence but we are definitely advocating for ourselves.”

Whether that “we” refers to transgender, LGBTQ+, or Taiwanese people writ large, I didn’t ask to clarify—struck at that moment, as I often am, biking through Taipei’s shaded sidewalk arcades into the humble night market-lined alleyways, by how much there is to learn from this island’s people and their urgent spirit of self-determination.

Top photo: A Taiwanese Pride flag flies over the crowd at Taipei’s 5th Annual Trans Pride March