TAIPEI — Three days before Taiwan’s general elections this past January, under the canopies of Bailan Street Market, Miao Poya reached over displays of fresh produce and steaming woks to shake every vendor’s hand all along the narrow street. Most mornings, this open-air bazaar is packed with elders slurping breakfast noodles or gossiping, one arm often preoccupied with pink fruit bags, the other with hand gestures. But today many were listening as Miao’s steady bass voice cut through the noise, a headset curling around the left side of her pixie updo. She was canvassing to represent Taipei’s sixth electoral district in the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s unicameral legislature, for the next four years.

Ah-Miao, as her supporters affectionately call her, could not be more different from the typical Taiwanese politician. Although already a two-term Taipei city councilor, she is relatively young, solidly middle-class, openly lesbian and the only elected official or active electoral candidate from Taiwan’s Social Democratic Party (SDP). Trailing behind her, I watched as she greeted an elderly demographic in a district known for its affluent, conservative and religious base.

As she handed out tissue packets and red tote bags with her election slogan—“Elect Miao Poya: Elect the right person in Da’an District, Set Taiwan on the right path!”—a middle-aged woman with an amber-red bob and black tweed jacket grabbed her by the shoulders and animatedly wished her luck. A silver-haired man stopped his motorcycle to bump fists (twice) with Miao and tell her, chest out, that he’d already recruited 27 votes for her.

I asked a nearby fruit vendor if she was familiar with Ah-Miao, specifically her queer identity and activist background. As she handed me my change and a bag of tangerines, the vendor tightly gripped my hand.

“She is honest with herself and us,” the woman said. “Shouldn’t we have politicians who inspire us to become ourselves so Taiwan can become a truer democracy?”

I was surprised to hear the vendor normalize Miao’s identity. Even after same-sex marriage was legalized here in 2019, many elected officials remain closeted, due to either pressures within their political parties or socially conservative constituencies, Wong Wong told me. Wong is the advocacy and civil-engagement project manager at Taiwan Equality Campaign, a political advocacy and education organization that attempts to boost openly out LGBTQ+ political participation from the current national level of 0.0002 percent.

As both an identity marker and a policy focus, “the LGBTQ+ issue is commonly known as ballot-box poison,” she said.

However, despite a relative general silence about LGBTQ+ issues in news headlines and presidential debates, I encountered Miao and a constellation of other legislative candidates—all women and queer representatives of Taiwan’s smaller, lesser-known political parties—who had built campaigns that recenter and normalize LGBTQ+ visibility in Taiwanese politics and the public eye. Beyond LGBTQ+ representation, these candidates also frame their political participation as steps forward in a broader social movement to advance Taiwan’s young democratic experiment, which is less than three decades old.

Ah-Miao lost her election bid. Nevertheless, in her concession speech in front of an intergenerational, gender-diverse crowd that openly wept over her loss, she said: “Today is yet another step forward for our democracy.” And despite broader losses for LGBTQ+ candidates, their campaigns represented progress for establishing a queer and gender-inclusive version of Taiwanese politics.

The LGBTQ+ issue as ballot-box poison

LGBTQ+ and gender issues have been fairly out of sight in Taiwanese electoral politics, and every political figure and activist I met was quick to tell me why.

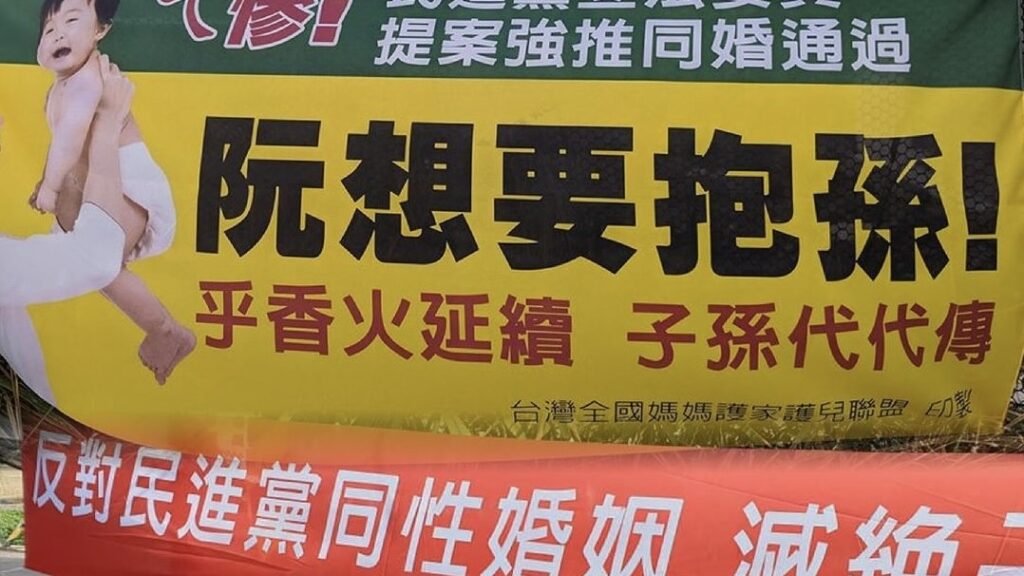

In 2018, a Christian group called the Coalition for the Happiness of Our Next Generation put three referendums against the rights of LGBTQ+ people in front of the Taiwanese public. Funded by major tech moguls and conservative US-based organizations, the coalition plastered social media, night markets and television screens with messages that promoted “traditional family values.”

At the same time, a companion group known as the Rainbow Moms coopted the rainbow insignia and distributed flyers arguing against LGBTQ+ rights and sexual liberation, in metro stations, schools and voting booths. Those groups campaigned around three referendum questions: First, should marriage be limited to unions between one man and one woman? Second, should same-sex unions be protected outside the civil code, which would effectively limit rights? Third, should mentions of sexual orientation be removed from Taiwan’s gender-equality education?

A decentralized front of LGBTQ+ advocates put together their own referendums, reframing the questions to support same-sex marriage and gender-inclusive education. The result was heartbreaking to many supporters. Just over 72 percent of Taiwanese voters—approximately 7.6 million people—voted against same-sex marriage, more than twice as many as had voted in support. A similar proportion voted to end inclusive sexual education. One of my queer friends told me they had contemplated suicide after seeing the results. Although the outcome had no legal bearing on the Legislative Yuan’s decisions, the public mood was resoundingly clear.

Due to an earlier judicial mandate, the Act for Implementation of Judicial Yuan Interpretation No. 748 passed in 2019, legalizing same-sex marriage. But the trauma and politicization of LGBTQ+ rights lingered. Indeed, Taiwan’s two major parties adopted polar opposite positions on the issue: The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), under outgoing President Tsai Ing-wen, supported same-sex marriage, and the Kuomintang (KMT) staunchly opposed it. While that divide is common—the DPP is also typically caricatured as pro-independence and the KMT as pro-China—many activists and laypeople were struck by how easily human rights became a tool for political jostling and electioneering.

“LGBTQ+ rights, especially, became the front-line battlefield for the two major parties,” Kang Yu-ni, a transgender activist and deputy director of public opinion analysis and communications for the Green Party Taiwan, told me. “Everyone else felt entitled to discuss and decide our rights, and the people left with the deepest wounds were us.”

During general elections in 2020, banners were seen across the country announcing that “Taiwan’s birth-rate decline is their fault!”—in reference to candidates who supported same-sex marriage—or “Same-sex marriage will mean the end of grandchildren in Taiwan!” Some voters blamed their candidates’ losses solely on their support of same-sex marriage, giving credence to the persistent idea that LGBTQ+ issues are “ballot-box poison.”

Many who attacked the DPP and other progressive parties supporting same-sex marriage “went so far as to say that such-and-such legislators would lead to Taiwan’s doom,” Wong said.

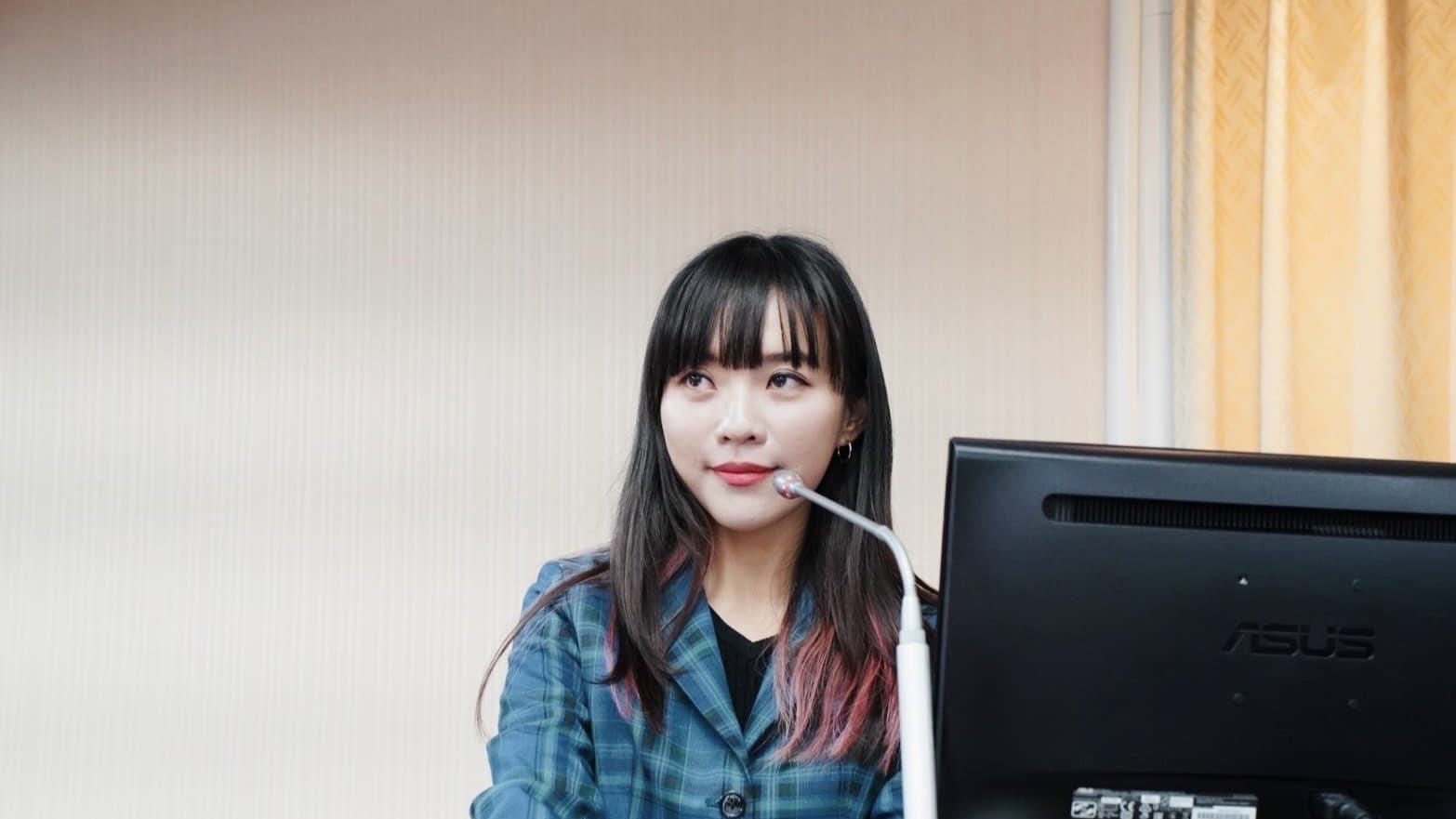

Huang Jie—who became Taiwan’s first openly out national legislator after winning her district race in this year’s election—bears her own wounds from that era. In 2018, she entered politics as a city councilor in Kaohsiung, Taiwan’s third-largest city located on the island south, and immediately sought to establish a citywide gender-equality oversight committee. However, the proposal was vetoed eight times by her fellow councilors.

“Once, as soon as I left the council chamber, I cried and wondered to myself, does this hostility genuinely represent Taiwan’s society?” she told me.

Recalling misogynistic and homophobic comments she received from both colleagues and the public, Huang chuckled, as if repressing her frustration. When I met her in her new office in the Legislative Yuan a few weeks after the elections, it was difficult to imagine her—poised in a cropped, blue-black plaid pantsuit, calmly responding to my questions despite a barrage of phone notifications on a busy Friday—in tears. Thanks largely to a restructured city council, over the last six years, Huang finally established a gender-equality oversight committee, successfully advocated for gender sensitivity training across industries and pushed Kaohsiung to become an LGBTQ+-friendly tourist destination.

Perhaps that’s the lesson. LGBTQ+ people, including politicians, have had to learn to steel themselves against assaults, learning when to parry and when to bite their tongues. On the campaign trail, Huang was tactical about when and where she brought up her sexuality.

“In the wake of the 2018 referendum, although time has softened the tensions, many people are still reluctant to bring up LGBTQ+ issues, to allow our identity to be a tool of manipulation,” she said.

Huang and Miao, the two highest-profile LGBTQ+ candidates from the past elections, both received negative attention for their sexuality on talk shows and social media. But Leo Chen, an advocacy and digital communications specialist at the Taiwan Equality Campaign, emphasized that compared to the 2020 general elections, individual attacks sharply decreased. The critical banners also did not return this year, which Chen considers a win.

Since 2022, he has managed and grown Taiwan Equality Campaign’s PrideWatch, a grassroots-driven digital platform where voters can hold politicians accountable for their campaign statements and promises during and after the election season. On each candidate’s page, politicians and voters can upload information, links or documents to co-create a running tab on the candidate’s commitments to a gender-friendly Taiwan.

For example, at a youth forum in November 2023, Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) chairperson and presidential candidate Ko Wen-je was asked how he would concretely create more LGBTQ-friendly educational environments. In response, he discussed the general need for more psychological and mental health care resources in secondary schools and universities, starting off his three-minute monologue with: “If we extend the LGBTI [identity] to include other kinds of psychological and emotional disorders…” On Ko’s PrideWatch profile, a voter linked the video and commented, “Ko insinuates that being LGBTQ+ is a form of mental illness, which is very homophobic.” After a friend heard the incident on the news, she immediately checked PrideWatch to see if there was a record. “I don’t know if I can change how someone will vote, but I can at least show them the facts.”

Overall, though, such explicit homophobic comments have become the exception. Over 100 candidates from across the political spectrum filled out a PrideWatch questionnaire asking them to commit to creating a gender-friendly environment. The number has only increased with each election cycle.

An equilibrium seems to have been established. Gender and sexuality were no longer major points of contention during this year’s election. But underlying the calm were an enduring caution and timidity to test the endurance of the “ballot-box poison,” as reflected in the major parties’ indistinguishable and moderate gender policies.

In late December, 27 civil society organizations released the results of a “Gender Policy Questionnaire” that invited political parties to explain their visions and policy blueprints for the next four years. Of the three major parties—DPP, KMT and TPP—they wrote: “Unfortunately, their responses to the civil groups regarding gender policy issues were disappointing, as most of them did not provide direct answers.”

Taiwan’s movement parties as a hopeful opening

Four parties did garner positive reviews on the gender policy questionnaire, however: the New Power Party (NPP), the Taiwan Obasan Political Equality Party (TOPEP), the Green Party (GPT) and the Taiwan Statebuilding Party (TSP). Coincidentally, they emerged as the fourth through seventh most successful groups, respectively, in the 2024 legislative elections.

Taiwan is constitutionally a multi-party democracy, and, since the end of martial law in 1987, hundreds of alternative parties have participated in local and national elections for posts from the presidency down to county chiefs. Since Taiwan held its first democratic elections in 1996, the presidency and legislative majority have flipped between the KMT and DPP in eight-year intervals in near clockwork. This year was an exception. Although the DPP has been the ruling party for the last eight years, leading many to say it is occupying an increasingly centrist position to “satisfy the masses,” it prevailed in this year’s presidential election yet again.

Of the 14 other parties that participated in the 2024 elections, the four above are known as “movement parties,” which the sociologists Ho Ming-sho and Huang Chun-hao described in 2016 as “an ambitious attempt to convert [social] movement activism into political power.” Those activists see the party system as a tool to electioneer for social issues, evolving from crevices of mounting resentment toward the mainstream DPP and KMT parties that developed into full fissures in 2014. That was when a three-week student-led occupation of the Legislative Yuan to protest the KMT government’s closed-door trade deal with China, called the Sunflower Movement, catalyzed a generation of young people to bring activist concerns into legislative chambers.

Earlier movement parties from the 1990s had focused primarily on class and labor issues. Ho and Huang note that because the Sunflower Movement drew support from a wide swath of society, its emerging leaders developed platforms encompassing a broad range of values rooted in Taiwanese self-determination and progressivism, including election reform and gender equality. Movement parties were tightly linked to the marriage-equality drive; for example, GPT fielded openly LGBTQ+ candidates as early as 2010. As of this year’s elections, at least four other movement parties have followed in GPT’s footsteps.

Energy around the movement parties mounted in the years directly following the Sunflower Movement. Directed by some of the movement’s key figures, NPP won five legislative seats and incited waves of interest in a “third force” in Taiwanese politics, or a formidable alternative to the two mainstream parties.

But over time, the Sunflower Movement’s momentum began to fade. Dafydd Fell, a political scientist and director of the SOAS Centre of Taiwan Studies at the University of London, wrote of local elections in 2022: “The general picture is one of the challenger parties being further squeezed out of the party system.”

By 2022, all but one of the movement parties had lost some or all of their legislative seats, which scholars generally attributed to a lack of both intra- and inter-party cooperation. When party members were not confronting internal fault lines, they were challenging other movement parties in the same districts and splitting votes. When I asked Chen and Wong about Taiwan Equality Campaign’s view of the movement parties, they were adamant in their praise even as they acknowledged the challenges.

“Small parties have made huge contributions to the diversity and sustainable development of our political system, most notably with their strong sense of ideals,” Chen said. “But our system is indeed inhospitable to small parties.”

In addition to the huge financial and human resources at the hands of the mainstream DPP and KMT, Taiwan has adopted a mixed-member majoritarian system for its legislative elections, in which each citizen casts one vote for a district-based candidate and another for a political party. Thirty-four at-large seats are determined by proportional representation for the parties that receive more than 5 percent of the vote. Because the established power of the mainstream DPP and KMT makes it difficult for small parties to win district races, most of them pack their at-large lists with political celebrities in hopes of overcoming the barrier.

But not a single movement party passed the 5 percent mark in this year’s elections. Beyond the systemic factors, Fell writes, DPP had “embraced or stolen many of the issues that movement parties advocate, such as LGBTQ issues. While DPP had been quite low-key in its advocacy of same-sex marriage in 2016, this was something that featured quite prominently in DPP’s 2024 campaign advertising and rallies.”

TPP’s rise as a third major party and most viable challenger to the two mainstream parties vacuumed up a large contingent of voters who typically look toward the movement parties. At a pre-election event in early January, a voter asked a panel of scholars and activists if it was worthwhile supporting a small party or its candidates. Are they not just visionaries? Would a vote for them make any difference when it’s almost certain they won’t win?

From a quantitative perspective, the answer to that question might be a resounding no. The 2024 elections could only be seen as a disaster; no movement party candidate mentioned in this article or elsewhere won a race, and nearly all parties lost voter support. The power of Taiwan’s three primary parties feels written into stone.

However, Miao emphasized that movement parties “should not aim to become the third-largest party or divide Taiwan’s political landscape into three equal parts,” she said. “Rather, they should aim to develop a political spectrum that firmly maintains Taiwan’s position as a free and independent nation and marginalizes the pro-China parties.”

Miao added that, practically, this spectrum can only take hold in the form of electoral seats. But on the long, winding road to the political landscape Miao describes, beneath the surface of stacked statistics and systemic barriers, I found several pioneering candidates who remain resolute not only in their openly queer identities and platforms but also in their commitment to Taiwan’s special brand of democracy. That is to say, the game of elections is being slowly rewritten by a women’s grassroots party headed by a married lesbian, the first transgender woman to run for elected office and an openly lesbian city councilor opening doors to a more transparent democracy.

A core of motherly concern: Taiwan’s grassroots women’s party

Leading up to any election, candidates canvas their districts in a tradition known as saojie baipiao, literally “sweeping the street for votes.” With megaphones and ice-cream-truck-esque theme music everywhere, streets become a call-and-response symphony. Candidates ask for voters’ support, and supporters shout back phrases like “Frozen garlic!” a homonym for “get elected” in Taiwanese Hokkien.

Major parties host rallies that rival K-pop concerts, while individual candidates stand on soapboxes on street corners, rain or shine. The spectacle has become routine for many voters.

Candidates with the Taiwan Obasan Political Equality Party (TOPEP) added two unique charms to their appeals: all their signs were Barbie-themed and an energetic mob of kids, listening (or not) to their mothers promoting democratic reform, paraded through the crowds, often with microphones in hand.

Also known as the Obasan Alliance, TOPEP is Taiwan’s first and only women’s grassroots political party, which grew out of parent-child co-learning groups organized by the Association of Participatory Parental Education in Taiwan. Beginning in 2012, those groups set out their mission as ending the legacies of intergenerational trauma and creating safer, child-conscious environments. While their children played freely in local parks, parents shared non-intimidating caretaking practices that respect children as equals rather than subordinates. If families practice dignity in the household, the rest of society would follow, the thinking goes.

However, many parents quickly realized that those around them were not following along. For example, decisions about playground equipment and water access in public parks were being made without their or—more important—their children’s input. All of TOPEP’s work and policies are rooted in this core value: how to protect children’s rights to enjoy a dignified life, from playground construction to family-friendly transportation to air pollution. By 2016, parents began holding workshops with other political parties and NGOs to advance their own perspectives on national debates around nuclear power, the death penalty and LGBTQ+ rights, among other issues. In 2018, 21 mothers ran in local elections without any party affiliation, cumulatively receiving 80,000 votes. The following year, TOPEP officially registered as a political party.

In an interview, TOPEP Secretary-General He Yu-rong joked that that was the spirit of “obasans,” a Japanese word that typically refers to older women in Taiwan.

“Everyone thinks obasans are nosy and love gossip,” she said. “We want to channel that energy into politics—into scrutinizing budgets, reviewing policies and confronting injustices like a typical obasan, hands on hips, chiding society for bullying the weak.”

When I met Shen Pei-ling and Lin Shih-han, TOPEP’s deputy secretary-general and acting chairwoman, respectively, they had just channeled that energy into a news conference at the Legislative Yuan’s Research Building. On election day, they recorded at least 17 incidents in which parents with children under the age of six were denied entry to polling sites, in direct violation of a national law passed four years ago. Not only did that deny children a firm understanding of democracy from a young age, they argued to the Central Election Committee, but it also follows a trend in which mothers are forced to choose between their children, their careers or democratic participation. After the news conference, I walked past a sea of black-suited men silently typed on phones or waited for the elevators in the Research Building’s austere lobby. In the lobby café, where a cluster of round, wooden tables and teal-cushioned chairs were tucked away in partial privacy, women wearing the party’s signature off-white vests huddled together, discussing party affairs in the same breath as their plans for the upcoming New Year holidays.

“No other party is going to bring this topic to the Legislative Yuan,” Lin told me, reviewing how the news conference went. “Yes, the Legislative Yuan may consist of more than 40 percent women, but in Taiwan, our patriarchal culture is directly linked to economic status. We are always a man’s daughter, wife or beneficiary.”

You will rarely find a man at a TOPEP rally. Instead, a group of kids and women might be singing, “O-ba-san! We’re here, we’re here!” in high-pitched harmony. At one rally, on the side of the road in central Taipei, an elementary school girl carried her toddler sibling in a baby sling wrapped in front. As her mother began to chat with a passerby about TOPEP’s policy platform, the girl snatched her mother’s mic and stood at the corner of a busy intersection.

“The ‘small’ in our party’s name represents children,” the girl said cheekily. “I am standing here for myself.” (The first character in TOPEP’s Chinese name literally means “small,” but in this case technically refers to ordinary people and the party’s twofold pledge to lower the barrier to political participation and bring ordinary people’s views into Taiwanese politics.)

At another weekend rally in Ximending, one of Taipei’s busiest shopping districts, a group of mothers and their young children recorded a popular online dance trend. As they laughed off their mistakes, a college student sheepishly approached to thank them for supporting LGBTQ+ families beginning with the marriage-equality movement and continuing to the present.

By challenging the stereotypes of who is allowed to be a politician through its rallies, TOPEP’s existence is already overturning the nature of Taiwanese politics. In addition to representing mothers and children, one of its primary considerations was how to bring marginalized intersectional voices into the Legislative Yuan. Whereas most parties pad their lists of at-large legislative candidates with celebrities or issue-area experts, the Obasan Alliance’s first candidate was the mother of a child with special needs, a largely invisible issue in Taiwanese politics.

The second candidate, Lin, a married lesbian, focused part of her platform on LGBTQ+ elderly care. When I asked why that was one of her primary issues, she laughed and said: “It’s because I’m in my 40s and I can’t keep ignoring this issue anymore!”

Lin was animated throughout our conversation, smiling frequently. While not a mother herself, a motherly form of leadership was clear in the way she encouraged her colleagues to speak up or fill in gaps. But in the context of old age, not being a mother also means the Taiwanese concept of “raise a child to secure comfort in old age” (yang er fang lao) doesn’t apply to her.

“That creates a very particular anxiety among LGBT+ people in Taiwan,” Lin said. “Many families are not concerned with whom their child loves as much as who will take care of them in old age or their economic status. As a whole, though, we want to construct a society where all elderly individuals can choose how they want to be cared for and create options to age in place.”

That balance between vision and grounded reality is evident across the party’s platform. When I asked members to clarify specific policies for bridging the gender wage gap in Taiwan or elaborate on how they might support #MeToo survivors, they had ready responses, embodying the spirit of the meticulous obasan. This spirit extends into TOPEP’s internal organizational procedures and structures. The political scientist and Taiwan scholar Lev Nachman has argued that the lack of routinization—or “the rules, regulations and bureaucratic systems by which party behavior becomes predictable”—was a key reason for the decline of other movement parties. On the other hand, TOPEP sought to create to embed consensus as a guiding system from the start.

For example, the choice about whether to print custom tissue packets—a standard, even trivial component of most other campaigns—was collectively deliberated in light of the party’s values around environmental protection. TOPEP ultimately decided to print only a limited number of packets to reduce plastic waste. Even over an issue as controversial as Taiwanese independence, Shen said, TOPEP members found consensus in a slightly circumspect manner, emphasizing how Taiwan can develop a resilient and prepared public with policies such as establishing community food reserves, strengthening the film industry as a form of public diplomacy and reforming the tax system to support public facilities. The party’s 2024 legislative platform spanned six pillars ranging from children’s rights to labor rights to Taiwanese sovereignty—and were all determined in a similar fashion.

As Lin told me, “My role as acting chairwoman and background as an advocate does not make me any more important than other party members.” Indeed, TOPEP is collectively led by 15 executive committee members. To join the party, applicants must be vetted and recommended by two members who assess applicants in light of the party’s core values.

While TOPEP did not reach the 5 percent level to enter the Legislative Yuan, it did manage to become the fifth-largest political party, winning nearly 130,000 votes in its first national elections. Moreover, since the elections, its flag has waved with crowds at Tainan Pride, Tibetan Uprising Day marches and other events. Rather than retreating from the public, TOPEP has continued to build a grassroots base of support that extends far beyond the election.

Politics as a form of protection for Taiwan’s transgender community

As we walked into a side room adjoining the Taipei office of the Green Party (GPT), Abbygail Wu (Wu Yi-ting) showed me the canvassing placard she used during this past election. She was among GPT’s eight at-large legislative candidates, all women with progressive platforms that ranged from marijuana legalization to migrant labor rights. Two pieces of beige cardboard, edges slightly frayed, were taped together over a wooden stick to form the sign. What looked like nine pieces of A4 paper were glued down to form her campaign profile image: Wu, hair draped over her shoulders, carrying a keyboard (to represent her cybersecurity engineering background), with the words “Used to be a man, now a woman” boldly printed above her name.

Wu chuckled as she recollected multiple incidents when people stopped dead in their tracks to look at her and her sign.

“I loved seeing their flabbergasted reactions,” she said.

Given that she has advocated for transgender rights over 15 years, little fazes Wu at this point. Indeed, she welcomes the potential for shock. In addition to her blooming career in politics, Wu is the founder and executive director of the Intersex, Transgender and Transsexual People Care Association (ISTSCare), a nonprofit that aims to support people who do not identify within a gender binary. The organization made its initial splash during Taipei Pride 2013, when Wu led a group of transgender men and women, naked except for body paint, that called out what they termed the hypocrisy of the gender binary.

But beyond her love for the shock factor, Wu entered politics to extend her reach as a social and community advocate.

ISTSCare’s focus “has always been on building community as a means of survival,” she said. Many of the people who seek support through the organization are economically disadvantaged, unemployed or facing various issues at home. She recounted an incident last year when a trans man was barricaded in his home, his phone and identification documents confiscated by his family so that he would not be able to undergo hormone replacement therapy (HRT). When someone from the ISTSCare community forwarded the information to Wu, she immediately took action. She rented a car that night, arrived at the man’s house at 3 a.m. and brought him to stay with her before consulting a domestic violence shelter the next morning.

Wu has passed through her own periods of economic insecurity. She rose to moderate fame in 2008 when she posted on a Taiwanese bulletin board about being unemployed due to discrimination over her transgender identity. Other times, she went for days without a proper meal, using her savings to travel to Pingtung, in Taiwan’s south, to mediate between a parent and child who had just come out. Ahead of the Lunar New Year, Wu planned multiple dinners for people who did not have family to spend the holiday with, asking for only enough money to cover food and drinks.

Indeed, for Wu—whose “24/7 includes trans issues” but who has also been a labor and cybersecurity activist—politics gives visibility and connections to extend her influence.

Moreover, while this was her first time running in an election, she is no stranger to the process. In 2012, a transgender person was stopped and misgendered at a polling site by security staff. After news media reported the incident, Wu said a number of her friends had expressed frustration and hesitation to vote. Some 15 percent of transgender people has avoided elections or dressed up as the gender assigned at birth to avoid confrontations with staffers, according to a 2023 survey conducted by the Taiwan Tongzhi Hotline Association. In 2014, Wu worked directly with the Central Election Commission to add a clause stating election staff must respect voters’ gender identities. But some fear persists.

After a few informal iterations, Wu formally established the Rainbow Citizen’s Election Complaint Hotline this year to create an LGBTQ-friendly voting environment. She managed the hotline herself and received about four calls, mostly consultative as opposed to complaints of discrimination. She intends to manage the hotline every year in the future to ensure more protection against discrimination.

Wu’s participation in the elections provided still another layer of protection. When a store clerk told one of her friends, a transgender woman, she could not buy women’s lingerie, for example, she replied that there were already transgender candidates running for the Legislative Yuan so “how can you still discriminate against us?”

“And apparently it worked!” Wu told me, her eyes and mischievous smile widening. “When I enter the Legislative Yuan, I want to be the one to burst open the doors for trans and other marginalized groups to storm in.”

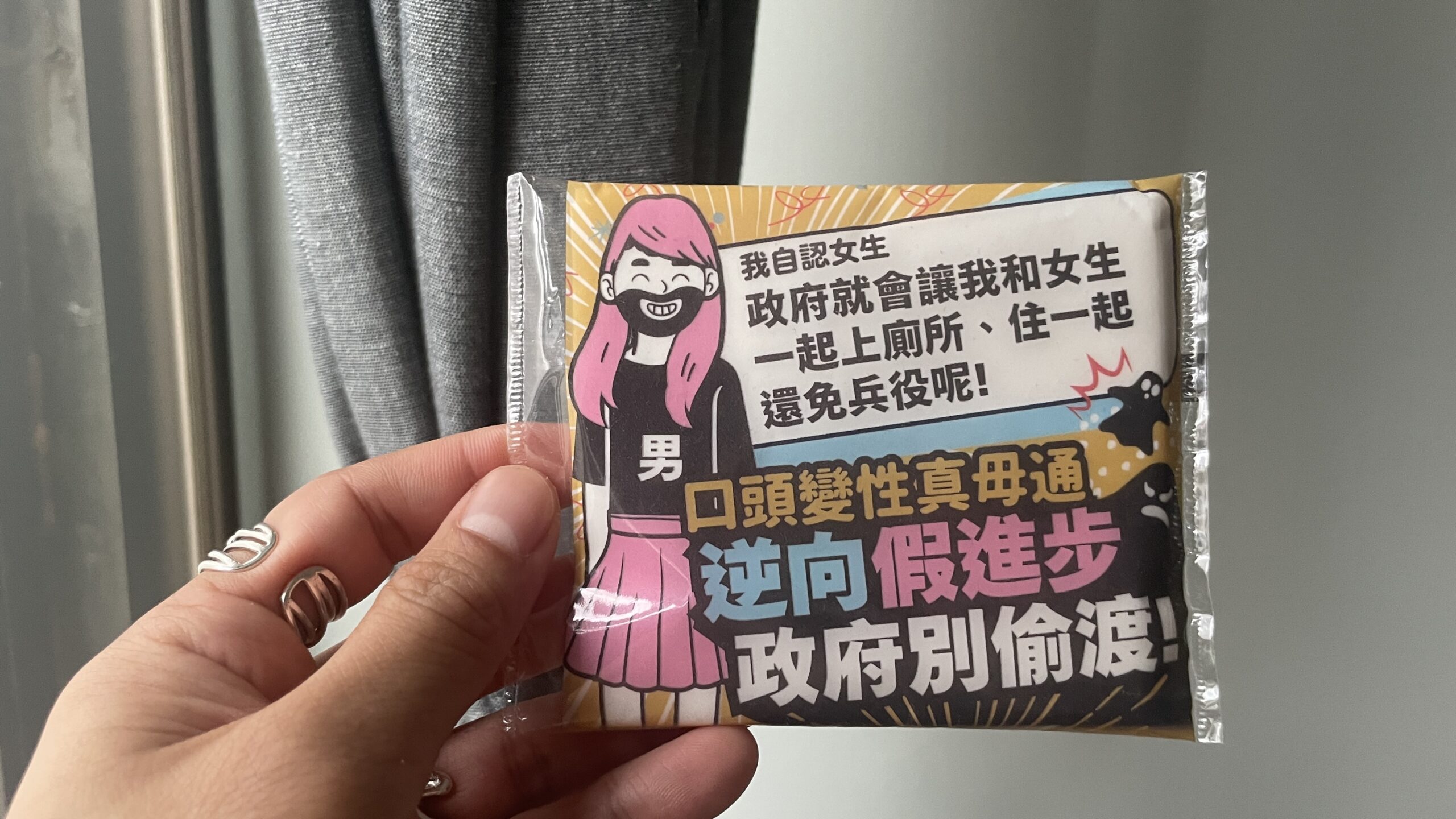

I’m pretty sure Wu meant that half-metaphorically, half-literally. While much of her advocacy work within ISTSCare has focused on individual acts of direct service, she is no stranger to confrontation. In this election, she and GPT butted heads with the Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU), which rebranded its political platform in opposition to transgender activists’ drive to abolish the surgery requirement for legal gender change.

Wu showed me one of TSU’s promotional tissue packets. On one side, a bearded woman is accompanied by a speech bubble that reads: “I identify as a woman. Therefore, the government will allow me to use female toilets, live with women and be exempt from military service.”

Founded in 2001, TSU espouses Taiwanese sovereignty, but contrary to most of the movement parties mentioned here (including TOPEP, GPT and SDP) who share similar platforms, TSU has become more socially conservative. At one Taipei rally attended primarily by older men and women, a candidate proclaimed TSU is the sole party that can defend the rights of women and children in the face of what it depicted as an encroaching gender ideology. At a news conference in December, three TSU members dressed in drag to prove a point that “cross-dressing does not mean one is a different gender.” Wu led multiple protests outside TSU’s headquarters in Taipei—ironically, right across the hall from GPT’s.

Ultimately, while both parties received fewer votes than they did in 2020, GPT still received three times more than TSU’s in the party voting.

“Sometimes having an enemy is good,” Wu said, alluding to both TSU and Ko’s homophobic comments earlier in the election season. However, rather than slipping into a traditional game of empty criticism and divisive slander, Wu wants to continue her political career to protect people such as trans men facing family abuse and underpaid laborers. One profound lesson she says she learned from the latest elections is that canvassing is an art form that’s deeper than simply making vacuous promises.

“People only want to hear politicians say empty phrases like ‘We want Taiwan to progress,’” she said. “And while I was initially resistant to the idea, I realized that connecting with people is all about finding a balance.”

Now her pitch is: “I want to become Taiwan’s first transgender legislator, and I want to improve everyone’s life so we can all live without fear in this society.”

People have started to listen.

‘See the real Miao Poya’

The night before election day, a crowd bustled around a busy intersection in Da’an District in central Taipei. Above, on a metro platform, passersby stopped to look down at the crowd, which numbered nearly 1,000 and was shouting “Frozen garlic!” loudly enough to echo, resoundingly, off the Starbucks building across the street. A large rainbow flag, the kind you’d need two hands to carry, rippled in the middle of the intersection next to signs with Miao’s name and others calling for women’s rights. I had exited the metro right into Miao’s final election rally, crowded with people of all ages and genders taking photos of her and immediately posting them to their social media.

At this point, Miao’s voice was slightly hoarse, dipping into a rasp at the end of each sentence. For the last nine days, she had followed a rigorous schedule of biking through the streets and soapboxing on major intersections, constantly thanking her constituents and rallying their continued support. But she was not just speaking to voters on the streets. Miao had livestreamed the final nine days of her campaign practically nonstop, from the moment she left her apartment building each morning until she returned home after 2 a.m.

“Communications scholars in the future will be studying these livestreams because we have created transparency powerful and sufficient enough to counter all the conspiracies we face,” Miao said in her final pre-election speech. “There is no political candidate in Taiwan—no one in the world—who has done it to this degree.”

By the time I stepped out of that metro station to join Miao’s final rally, I felt sadness welling up inside me. Because candidates are not permitted to campaign on election day, I was bracing myself for the livestream to end at 11:59 p.m. that night. A small community had formed around the YouTube comments—anywhere from 200 to 5,000 people were logged into the livestream at any given moment, even late into the night—complimenting Mia’s eloquence or asking Miao if she had eaten properly yet. (She often only snuck bites of a bento between rallies.) Her assistants would often read comments and questions addressed to Ah-Miao, creating what she described to me as a “truly bidirectional form of communication—my team and I wanted to create a concrete example of what politics should be.”

In the days leading to the nonstop livestream, Miao’s conversations with passersby—often undercover supporters or even staff members of her KMT opponent—were spliced and manipulated to emphasize her more controversial views. In addition to being an out lesbian, Miao had previously been involved in movements to abolish the death penalty, an extremely controversial and unpopular stance across Taiwan.

In late December, in the heat of the campaign season, a middle-school student was murdered on a school campus in New Taipei City by another student, prompting intense debate. While some district races saw debates about mental health care, family care and school security, Da’an District’s voters received an anonymous text message reading: “Do you agree with 1. Miao Poya’s advocacy for abolishing the death penalty? Or 2. Luo Zhi-qiang’s stance on carrying out the death penalty according to law?”

Incidents such as that one prompted Miao to take control of her own narrative through the livestream. But the broadcast was impressive not simply because Miao managed to do it at all but because it gave her a chance to model the kind of political discourse she hopes to see across Taiwan.

“I hope to establish a more scrutinized, open and transparent political culture through such actions,” she told me.

Over the course of the nine days, she was approached by characters of all sorts. Her opponent’s staffer attempted to bait Miao to discuss certain death penalty cases. A teenage boy questioned her after a streetside speech outlining her stance on Hong Kong for some 10 minutes. A man in a motorcycle helmet walked toward Miao in front of an elementary school, yelling, unprovoked, in Hokkien: “Your whole family will die! You will be killed on the road later!”

Miao responded calmly each time. Looking the staffer directly in the eye, she explained the facts of past death penalty cases until he had nothing else to ask. She walked the boy through her logic about Hong Kong, stopping often to make sure he had no additional questions. She told the man in the helmet, simply, “Thank you,” and moved on, trying to deescalate and direct nearby children away. Even as the bags under Ah-Miao’s eyes became more and more prominent, she did not lose her temper. While she is already well-known in the Taipei City Council for her debating ability and collaborative potential—after all, as the only SDP representative, Miao does not have a party faction to support her—the livestream was a unique textbook for communication across differences.

“The aim is to find joy and meaning in the process of engaging with different opinions,” she said at the Taipei International Book Fair in mid-February, presenting her memoir Let’s Take One Step Forward Together: Make Change Really Happen. Someone had asked her how to talk to people with differing views.

“We should not aim to take one step today,” she answered. “It’s about multiple steps over multiple months because the road to social change is travelled only with steady progress.”

Miao’s sexuality did not come up very much during the livestream, which perhaps is a sign of social change. As Chen told me: “Once Miao Poya entered the Taipei City Council, other councilors would no longer make discriminatory remarks toward LGBTQ+ communities. Moreover, in proposing or amending gender-related bills, other city councilors knew they could consult Ah-Miao.”

The “Ah-Miao effect” has spread to the internet. There’s something quite queer about being so transparent that any “closet” simply ceases to exist.

Together, another step forward

For the LGBTQ+ community, one way to think about this past election season is in terms of firsts. The first openly LGBTQ+ legislator to enter the Legislative Yuan. The first grassroots women’s party. The first transgender woman to participate in elections. (Huang Gia-Yeh, from my last dispatch, is technically the first transgender person to have participated in an election, albeit as a form of performance art. “I feel bad to take the title,” he said. “But I guess that means someone else will have to win soon!”)

None of the candidates dwelled long on those firsts, however.

“I find this moment precious because it signifies that voters are willing to elect [Taiwan’s first openly out legislator],” Huang Jie said. “But for me, I don’t give it much special attention because I look forward to a day when our identity does not need to be a special topic of discussion.”

The Taiwan Equality Campaign is already working toward that. Wong emphasized that the organization will spend the next year conducting research to expand the curriculum of its political training camp, which aims to increase the number of openly out candidates and political aides. The camp has already been held twice, and beyond the core skills needed to run an effective election campaign (such as selecting an appropriate electoral district, developing political platforms and calculating an effective budget), it serves as a bridge between LGBTQ+ candidates past, present and future—a support group for how to navigate the unique challenges of coming out or navigating sexuality in a political arena.

The organization is also continuing to expand PrideWatch’s influence as an accountability tool beyond electoral cycles and to improve on its inaugural LGBTQ+ policy whitepaper, a document created last June to advise parties on the current state and ideal future of LGBTQ+ rights. Taiwan Equality Campaign also look forward to conduct research on how political parties can better support LGBTQ+ candidates and prepare in advance for attacks based on candidates’ sexual orientation.

“We want to ensure that LGBTQ+ individuals can speak for themselves through legislation and electoral participation,” Chen said. “But it’s more than bringing LGBTQ+ issues into the Legislative Yuan.”

Indeed, while TOPEP’s obasans and Wu built platforms rooted in their identities as mothers and a trans woman, respectively, their campaigns started and ended in more inclusive visions. Following these legislative candidates, especially amid the geopolitical flurries that surrounded this election—not least Taiwan’s place in the antagonism between the United States and China—may have made me a far-fetched idealist. Most headlines about movement parties and other small parties claimed they are on the brink of shuttering or lying in crushing defeat. Perhaps it’s naive to hope for their success without significant electoral system reform, a massive feat.

Systematic factors after the election continue to put pressure on small parties. Not only did none of the movement parties reach the 5 percent threshold to enter the Legislative Yuan but none even attained the 3 percent needed for an annual government subsidy of 50 New Taiwan Dollars (just under $2), per vote—a lifeline for many. GPT, TOPEP and other parties have never received this subsidy, always having had to rely on grassroots fundraising.

But while materially very little has shifted, it seems the atmosphere has already been altered by the presence of these players in Taiwan’s political landscape. Miao is no longer livestreaming her life but in addition to continuing to serve in the Taipei City Council, she hosts weekly podcasts on political news and issues. The online audiences continue their compliments of Miao’s eloquence and demands that Ah-Miao take care of herself. GPT and TOPEP are participating in social movements and rallies and demonstrations around Taipei. TOPEP has also hosted “meet-athons” across Taiwan to engage potential party members and refine its platform with community feedback.

At the end of my conversation with TOPEP’s Lin, I asked what motivates her to stay optimistic, especially when parents still face daunting challenges. Looking at one of her colleagues, she said inquisitively: “I don’t think we’re optimistic. Are we?”

She stopped for a moment to think.

“On the contrary, I think we are pessimistically convinced that war or climate change will happen, which means we need to face them head-on,” Lin said. “It comes back to our identities as mothers, as caretakers. We don’t have the luxury of hiding in our rooms, waiting to be protected or for Taiwan to change.”

During all my interviews and conversations about the elections, I was reminded that Taiwan is indeed a young democracy. Just over 30 years ago, the country was still under the martial law of an authoritarian regime. The democratic experiment will not fully blossom overnight, just as the shackles of Taiwan’s past on people’s minds have not fully vanished. Taiwan is still growing up with its people, its movement parties, its growing LGBTQ+ community.

I think back to some children I saw at a TOPEP rally. While some younger kids were dancing around their moms, tugging at the edges of their off-white skirts, two girls were clamoring over microphones. I could make out only phrases here and there—human rights, children’s rights. But as I watched them giggle and attempt to corral each other to join in saying the party’s name in unison, I couldn’t help but laugh along.

Top photo: The night before the 2024 general elections, a truck with candidates from the Obasan Alliance, its volunteers and family members parades down the street in Chiayi City