The Great Famine of Mount Lebanon swept through what was then Ottoman-administered Greater Syria in 1915. A bad drought led to a bad harvest that year. Most remaining crops were swallowed by swarms of locusts. World War I was metastasizing and much of the population found itself caught between the Ottoman Empire, which joined Germany in 1914, and the advancing Allied forces.

Residents were surrounded by an Allied-enforced blockade at sea choking off supplies to the Ottomans. The Ottoman army commander, Jamal Pasha, imposed a counter-blockade that barred produce from entering the region. Those environmental and political circumstances led to the starvation and death of up to 500,000 people—the single biggest cause of death during the war.

During that time, an apocryphal story emerged about a ship with a murky provenance named Rozana that was sighted trying to break the blockade to deliver food to Beirut’s port. Each day, the beleaguered people of Beirut called out and sang to Rozana on the horizon, the story went. But the ship never came to dock.

The elegy eventually traveled inland and reached nearby Aleppo, the region’s economic powerhouse, which was not affected by the siege. Merchants managed to slip past the blockade by night smuggling in sustenance, saving Beirut from more starvation. The Levantine folk song “Al Rozana” has been refashioned by each subsequent generation, sung by celebrities from the Lebanese diva Fairouz to the late tenor Sabah Fakri. The song immortalizes the struggle of 1915 and the hope that your neighbors will come to your rescue.

Today, Radio Rozana—which translates as “the window that lets light in”—is among the dozens of Syrian-run media outlets operating in exile. They provide information for Syrians squeezed and scattered by the decade-long conflict in their home country. Most are part of an independent media landscape that starkly contrasts with the long history of government-censored media. The new outlets are cultivating a more open Syrian community, as well as bearing witness to and chronicling the opposition uprising, and leading a conversation on political consciousness, among other roles.

The importance isn’t lost on Ahmed Talab al-Nasr, a culture editor for Syria TV and a very busy man. “I don’t know if I should sit or stand,” he tells me pacing around our table at a café in a stylish, seafront mall in Istanbul’s Florya neighborhood along the Marmara Sea. “If I sit, I may not be able to eat,” he says with jaws clenched, listing all his planned work for the day. Quick to smile, showing off his white teeth, he tells his story of Syrian media in exile as he fidgets at a frenetic pace in his chair, shifting side to side, using his phone to share updates or as a baton to underscore a point, smoking on either his cherrywood pipe or a pumpkin-colored cigarillo, and drinking cups of tea.

The opposition television network he works for, which is part of a larger Syrian media group based in Qatar, launched in Istanbul in 2018. “The only good thing that the revolution brought was it broke the regime’s past blockade on information,” he says, clamping down on his pipe. As servers floated back and forth behind al-Nasr, he returned to his core message: the rise of independent, although imperfect, Syrian media is a boon to Syrian society and the diaspora.

Such outlets appear to be an example of communities coming together in need. Syrian families—both at home and in exile—face untold challenges, and journalists need to continue discussing change on the horizon.

* * *

The Assads, President Bashar al-Assad and his father Hafez before him, have had a media monopoly in Syria ever since the elder Assad declared himself leader in 1971 after launching a military coup. Information became tightly controlled through state-run newspapers and TV channels until the 2011 civil uprising four decades later.

Bashar al-Assad had taken power in 2000 after his father’s death, when he ushered in a short period of reforms known as the Damascus Spring in response to intense political activism in the country. He made some changes to freedom of speech and press, allowing for private television channels, newspapers and radio. But those freedoms were short-lived and by 2003, the country saw a return to business as usual with the state heavily censoring and editorializing media content. Disillusioned Syrians stopped bothering to follow the news altogether, al-Nasr told me, apathetic to tone-deaf coverage and fulsome praise for the country’s rulers.

“We used to joke that television in Syria even lies about the weather,” Ghaith Hammour told me. He helped found and edit SY+, an online platform that produces short videos from inside Syria. The joke rings true for the Syrian government’s media coverage in the first months of protests in 2011. During a series of demonstrations at a mosque in a neighborhood of Damascus, the state-run television channel, Al-Ikhbariyah Syria, described demonstrators as a group of worshippers merely praying for rain.

An even more egregious example of such disinformation occurred when the Syrian government media apparatus blamed both Al Qaeda and the opposition for a notorious chemical attack in 2013, as well as subsequent chemical warfare against civilians.

With state-run media failing to deliver accurate information, Syrians sought news elsewhere, initially from Arabic satellite channels, principally Al Jazeera. The Qatari state-owned network extensively covered the conflict’s early stages, providing Syrians with rolling reportage of the uprising supplying shocking images of violence.

Syrians also began launching their own outlets, with “citizen journalists mushrooming across the country,” Hammour said. Some 100 media initiatives began in Syria after 2011, according to the Reuters Institute. But the new media landscape was marked by explicit bias, a lack of professionalism and donor-driven agendas.

* * *

Lina Chawaf experienced the transition firsthand. She had worked in media in Damascus since 1992, including in radio since 2005. She fled Damascus shortly after the outbreak of violence in fear of continuing to live under censorship. In exile in France, she joined a group of Syrian journalists in Syria, Turkey and France who wanted a simple, direct way to bring stories from Syria to the burgeoning number of Syrians abroad. Thus began the story of Radio Rozana.

Over a phone call from Paris, Chawaf—the station’s first editor-in-chief and now its executive director—explained her inspiration to form a community radio station in 2013. Radio is easily accessible and cheap, therefore all the more important in a fluid conflict setting. Radio Rozana, supported primarily by a range of European media and donors, is based in and transmitted from Gaziantep, Turkey, less than 100 kilometers north of Aleppo. Chawaf and her fellow founders saw building community as the initiative’s core.

As the station grew its listenership (it had 10 million online listeners in October and millions more on air[1]), the station leaned into its communal character. “Our airwaves are for our listeners. We never cut the line on anyone,” Chawaf told me about those who call into the radio’s broadcasts. Initially, listeners were afraid to express themselves, with the wounds of censorship and the mukhabarat—colloquial for secret police agents—still fresh. However, over time, listeners have opened up, even to discussing sexuality and other traditionally taboo issues. “Rozana has become their media, their radio,” Chawaf said.

“People definitely still fight on air,” she added, laughing, “but discuss differences freely.” Along with the new acceptance of opinions, Radio Rozana is creating space for discussion. Chawaf believes the role of news media is to reflect reality, not change it. She feels validated in having achieved that goal in exile. Syrians still inside the country call in, Chawaf said, beaming, to say, “‘Rozana is like our friend. We sit and talk with you.’”

Now with 20 staff, the team has grown over the years, changing with its listeners. During an evening program dedicated to gender equality, a woman called in on air to describe physical and emotional abuses by her then-husband. “She thought this was completely ordinary,” Chawaf said. Hearing the experiences of other callers on air, however, she realized her situation was not in fact normal and requested help. The station’s staff connected her with a lawyer who helped her get a divorce. She later trained to work at Rozana and is now a staff member. “I still get emotional thinking about this,” Chawaf said softly.

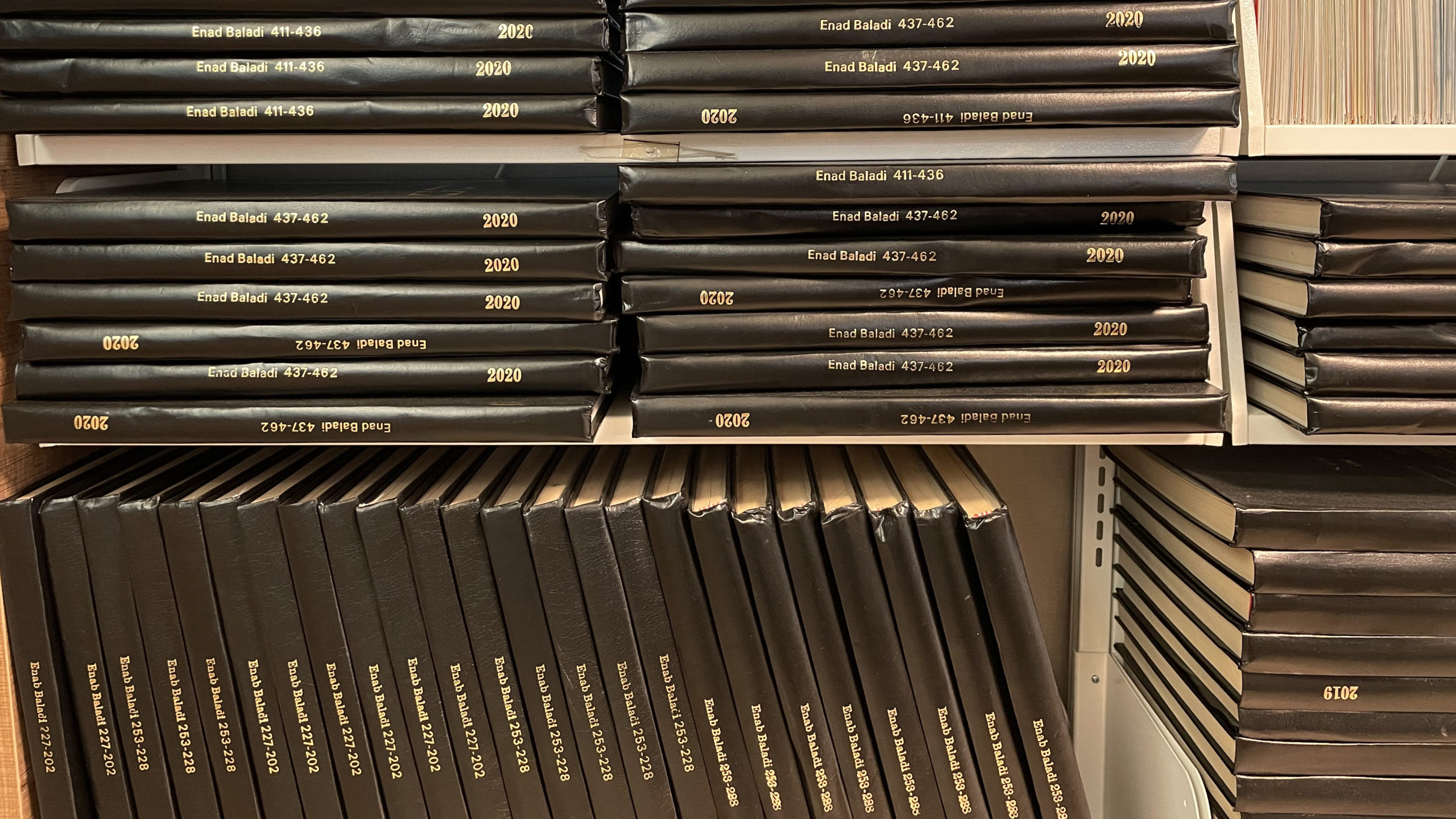

As the team at Radio Rozana works to create a sonic community, the newspaper Enab Baladi—which translates as “the grapes of my country”—bears witness to and remembers the atrocities of the Syrian conflict. The paper started in Darayya, a suburb west of Damascus. Each week, the editorial team publishes the names, stories and photos of civilians who had been detained. Such detainees were simply represented as a growing numerical tally by other outlets, but Enab Baladi provided details to humanize them and give these people the dignity they deserved.

As the Syrian uprising and ensuing war spread, so did the paper’s staff and coverage. Enab Baladi has been headquartered in Istanbul since 2014. On the fourth floor of a sterile building, inside a bustling newsroom, sat Jawad Sharbaji, the editor, at a large open table. Stacks of newspapers towered behind him. Serious, precise, yet laid back, he explained how the team has been binding the papers from each year, working backwards. They are currently at 2017. Picking up an edition from 2018, he said, “From these, you can read the history of the Syrian revolution.”

It has been said that the Syrian conflict is the most documented war in human history. However, only a dozen or so of the outlets that initially launched in the heady days of the revolution remain, as others closed due primarily to a sense of detachment or waning funding sources, as a result of a weaker regional economy and shifting priorities by international donors. This reality has put more pressure on established outlets such as Enab Baladi—which will celebrate its 10th anniversary next month—to provide coverage. That has never been easy, Sharbaji said.

He pointed to the editorial team’s defense of freedom of speech in the wake of the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris. In response to an editorial, Islamist militias in eastern Aleppo banned the paper’s distribution there. Readers would peruse the newspaper in secret before burning it. The weekly stopped distribution inside Syria altogether in 2018 after Hayet Tahrir al Sham, which controls Idlib in Syria’s northwest, denounced an article criticizing Abdullah Muhessni, a popular militant Saudi cleric. Hayet Tahrir al Sham demanded the article’s author come to Idlib to be tried. The ruling group employs censorship and detainment of journalists in an attempt to control the narrative—a tactic that has also been known to be used by the Syrian Democratic Forces, which controls the country’s northeast.

Enab Baladi’s senior staff decided to focus on the paper’s online presence, now printing only a thousand hardcopies each week. The website also has new features including a podcast series and, adapting to the reality of a new, receptive diaspora audience, a tab dedicated to Syrians living in Turkey. “One day, we will return to Syria and copies of Enab Baladi will be distributed on the street,” Sharbaji said.

In the meantime, the editorial team is also working to preserve the gains of a more independent Syrian journalism. Enab Baladi has launched several initiatives, including Maris—which translates as “practice” in Arabic—to both develop its staff as well as train young Syrians new to journalism. The paper offers both fellowships and workshops. “Never use a word or a photo that could hurt people or spread hatred,” Sharbaji said, stressing the need for journalists to be accountable to the wider Syrian society. But he ruefully noted that well-trained Enab Baladi staff often leave for more reputable and better paying regional and international outlets. “We are a failure of our own success.”

Earlier this month, Syria’s Education Ministry announced it would produce new education materials to “clarify the ideas and reasons that led to the war.” Such attempts to shape a single narrative around denial and accountability makes documentation of past events all the more important to circulate different perspectives. But the editorial team of the online magazine Al-Jumhuriya thinks it is no longer enough.

“Look, not only does the world have Syrian fatigue,” Karam Nachar, the executive director, told me as he puts down a tray of baklava, “Syrians have Syrian fatigue.” Tucking in his shirt and sitting down in a comfy armchair in a leafy Istanbul neighborhood, he continued, “The revolution is over and we need to act accordingly. It’s not an easy conversation. Now only being in opposition to the regime is insufficient in terms of an identity.”

Other outlets typically started out extremely localized. Those platforms were on the ground with cameras, raw footage and data. Al-Jumhuriya’s founding members saw a gap they could fill as experienced academics and writers living all over Syria and the world. The majority had longstanding relationships with one another since the Damascus Spring back in the early 2000s. “We were targeting a very specific type of reader; a constituency that was politically liberal, and more and more felt marginalized, opposing both the regime and the Islamists,” Nachar said. The media collective began to produce content in March 2012.

The editorial team aims to safeguard a space to discuss pluralist belief systems and has produced and featured content on everything from liberal thought to gender and sexuality to identity issues for the growing diaspora. Nachar, who is also a historian, is proud of the magazine’s focus on narrative history.

He shared some of the positive feedback over an article about the country’s experience immediately after it split from the United Arabic Republic, a political union between Syria and Egypt, between 1958 and 1961. “We have lived in a desert of ignorance. Fifty years of authoritarianism and, before that, a tumultuous period of coups will do that to you,” he explained, “We are trying to further a more open political discourse.” Paraphrasing Hannah Arendt’s 1961 book On Revolution, Nachar says, “Building a house of freedom is so much more than tearing down the system that was.”

The magazine has become important not only in Syria but the wider region, according to Yassin Swehat, the editor. “Syria is no longer a local issue and it is heavily connected with what is happening in the whole world,” he told me. “Where I come from [Raqaa city in northeastern Syria, along the Euphrates River] we have Russia and the Americans. The last time this happened was in Berlin’s [Cold War] occupation. It’s Syrianity,” he added, explaining how local developments in Syria reflect geopolitical dynamics.

Inside Syria, Swehat said, people struggle to be remembered by the rest of the world. “Don’t miss us behind only seeing al-Assad,” he said. “We are here, hello!” One of Al-Jumhuriya’s recent commentaries widely followed inside Syria included a debate on the efficacy of the Caesar Act, US legislation that came into effect in 2020 sanctioning the Syrian government but which has mostly affected the population.

* * *

Despite the Syrian media transformation over the last decade, the future is uncertain. Funding and sustainability keep chief executives up at night. Unable to charge Syrian readers, they seek contributions from either fatigued donors or benefactors flush with cash and political agendas, which presents a host of dilemmas.

As the number of media outlets dwindles, journalists face increasing pressure from a kaleidoscope of political, militant and criminal groups that run the areas from which they report inside Syria. Those in exile also have to navigate the media politics in the countries in which they are hosted. Still, as Ahmed al-Nasr, the editor at Syria TV, reminded me while collecting his various tobacco paraphernalia when we were leaving the café, “Given all the challenges, the fact that we as journalists still exist is a success.”

Top photo: Radio Rozana’s studio (Radio Rozana)

Endnotes

[1] It is nearly impossible to measure Rozana’s reach through its FM broadcast, Chawaf says.