The Century Foundation invited me to contribute a chapter on Egyptian cartoons and comics for Arab Politics beyond the Uprisings: Experiments in an Era of Resurgent Authoritarianism. This chapter builds on extensive fieldwork conducted during my two-year ICWA fellowship, offering the most comprehensive study to date of the challenges facing cartoonists in Egypt. I am grateful for the perceptive feedback provided by co-editors Thanassis Cambanis and Michael Wahid Hanna, who helped sharpen my argument and analysis. The book, which features chapters from a number of distinguished scholars and journalists, will launch in June in New York and Beirut. It can also be read at the Century Foundation’s website here.

***

Abstract: In print and online, Egyptian cartoonists have created sites of political dissent in defiance of a state-sponsored crackdown on opposition movements, public protest, and free speech. Based on analyses of cartoons and interviews with the artists, this chapter argues that cartoonists have expanded the red lines of acceptable discourse by forging workarounds and challenging official censorship. In the absence of traditional spaces for free speech and political dissent, cartoonists serve as a vanguard for pushing the envelope, opening opportunities to criticize authoritarianism and abuses of power by the state.

What does it mean to draw edgy cartoons when the edge is constantly shifting? The past five years have brought considerable political change to the Middle East and North Africa, and each new regime or policy affects the considerations of caricaturists and comic artists. Navigating these moving edges is a difficult but fundamental part of the independent cartoonist’s daily work. The red lines are regularly redrawn by a variety of political forces as well as the cartoonists’ personal considerations and political preferences. For cartoonists who push the limits, there always exist the risks of lawsuits, intimidation, and in rare cases violent attacks. But these limits, counterintuitively, animate creative dissent.

Since the 2011 uprisings, a new generation of Arab comic artists has built their careers on confronting boundaries and eviscerating establishment views. Underground, avant-garde, and outrageous, these artists have started horizontal comic collectives that persistently flout taboos. They are producing publications that reflect the ethos of insurrection in spite of political stagnation.

Such a task is difficult in the political void that has transpired in contemporary Egypt, as the vast majority of columnists and commentators have played along to the government’s sheet music. Nevertheless, a cohort of independent cartoonists has created a vibrant political discourse within their daily contributions to broadsheets and in newly established alternative comic publications. With a rich tradition that stretches back more than a century, the form of the political cartoon itself is significant in Egypt. It figures prominently into the local press, with caricatures often appearing on the front page of newspapers and magazines; some publications run more than half a dozen per issue. In this way, cartoonists in Egypt reach a larger audience than their American counterparts. Furthermore, new comic zines have been influential. Even though such alternative comics are published in limited print runs, they have effectively convened critically minded audiences at public events and, in turn, spawned other likeminded publications in print and online.

Egyptian cartoonists’ work is all the more poignant set against the backdrop of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s reign, which has advanced an autocratic state so extreme in its suppression that prisons are overcrowded and military courts have convicted thousands of civilians.1 At least twenty-three journalists are incarcerated for charges including “disseminating false news” or “insulting” various state institutions.2 Public demonstrations are effectively illegal according to an October 2013 law, and many leading activists and journalists have been barred from leaving the country. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) of all stripes have been shuttered. The authorities’ occasional dragnets of downtown cafés known as activist hangouts and seemingly arbitrary raids of apartments cast a shadow over all participants in the public sphere. The expression of oppositional perspectives bears serious risks, and yet cartoonists have scarcely been deterred. Whether in newspapers or in alternative zines, cartoonists have emerged as adroit critics of politics and society, vocal oppositional voices within a spectrum of conformity. The question thus becomes how cartoonists have managed to exercise a much wider range of critical speech than other media actors.

Given their power to agitate authorities, cartoons and comics also act as an informal compass for tracing the constantly shifting red lines of permissible expression. But the relationship between red lines and humor is not necessarily straightforward. It is no coincidence that the funniest cartoons rub up against the laws and rules that restrict speech. Humor has a symbiotic relationship with censorship. When cartoonists break the rules, or come close to it, the result is a laugh line. When they embrace the rules and the powers that be, the punch line is propaganda.

Upon close examination of contemporary comics and conversations with their creators in Egypt, two significant trends stand out in the past decade. The first is the state’s tacit tolerance of symbolic and satirical attacks on authority, notably through caricature. While Egyptian satirists have always seemed to crack jokes about presidents, starting in 2005 in the independent Egyptian newspaper Al-Dustour, cartoonists began directly caricaturing Hosni Mubarak (president from 1981–2011). Since then, the red lines of acceptable speech have shifted along with the regimes that emerged in the subsequent revolution and coup. But the cartoonists who first caricatured Mubarak left an indelible mark on the public sphere. Since Sisi’s 2013 coup against Mohamed Morsi (elected president in 2012), authorities have attempted to suppress dissent, especially in the form of criticisms of Sisi, who became president in June 2014. Nevertheless, the volume and barb of pokes at the president have endured the clampdown. Online dissemination has helped, but crucially the fear barrier has been shattered by creative experiments advanced a decade ago.

The second fundamental change is the rise of comic publications for adults, first in 2008 with the critically acclaimed and quickly banned graphic novel Metro, and then in 2011 with the emergence of the alternative comics magazine Tok Tok. To distinguish this new generation across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), I will informally call them the Mad Cartoonists. They are “mad” in many senses: influenced by Mad-magazine-style comics; angry at the status quo; and madly defiant of laws and norms. This report will focus on the works of Egyptian cartoonists, as there are simply too many alternative comic artists working in the MENA region to explore them all in this limited space. Yet it is important to note that Egyptian artists are part of a wider trend of alternative comics throughout the region, with links that continue to deepen through international gatherings and publications. Though they are friends and supporters of each other, the Mad Cartoonists are by no means a political movement. Indeed, much of their work lacks overt political messaging, affinity to any party or movement, or policy prescriptions. But in today’s tyrannical political climate, radicalism—or even mere dissent or political opposition—comes in many forms, including shared aesthetics or a commitment to independence.

A Metaphor for Expression

Traces of a new visual culture are developing from within Egyptian media and society. New technologies and social media have also affected the world of comics, reinforcing these two trends. Importantly, caricature of the president and the emergence of comics for adults are related, their causes and effects intertwined.

Though readers—millennials in particular—eagerly consume the new comics in print and online, the dominant perspective of graphic narratives in the country is that of conservatism, regime protection and maintenance, and the repressive status quo. To understand the extent to which the Mad Cartoonists are outliers, it is useful to analyze them alongside the country’s conservative cartoonists.

One point to consider while reading comics is whether they obscure autocratic politics by providing a semblance of creative freedom in undemocratic contexts. The imagery of the safety valve has oft been used to describe this sort of pressure drop.3 The safety valve implies stark power relations, in which the regime tolerates a limited amount of dissent in order to reduce the likelihood of a larger insurrection. In this model, the regime’s omnipotent hand holds the power to twist on and off the spigot of critical speech, allowing a drip but never a deluge. That is because, from the state’s perspective, types of dissent that are only mildly oppositional and have limited distribution are mostly harmless and allow for the illusion of speech. I argue that the dynamics of political speech pertain more to the risks taken by individuals and, especially in the case of Egypt, the state’s ambiguous power in suppressing speech. A more nuanced way to portray this phenomenon, then, is to think of it as a speech bubble. While the notion of the safety valve has the potential of obfuscating the role that satirists play in building communities, the speech bubble suggests communication among personalities and a shared language, either visual or written. In this way, the speech bubble—whether an expression of dissent or support—can have an impact on discourse in or out of the frame. There is the potential for individuality, as each comic artist draws speech bubbles in a unique style. Speech bubbles can expand the frame of dialogue, creating more room for debate; they can be packed with information or they can be hollow. Obviously, “bubble” also suggests a vulnerable sphere susceptible to state intervention, a space that can be popped or float away like a helium balloon. But there is one thing in common between the state’s occasional suppression of cartoonists and independent artists’ clarion call of opposition through their ephemeral works: small-bore modes of opposition and dissent can be the start of much larger societal movements.

The speech bubble was glaringly apparent at the 2015 Festival International de la Bande Dessinée d’Alger. There, I met dissident Algerian cartoonists who published criticism of the despotic president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, in privately owned newspapers. They were invited to participate in the international comics festival hosted by the Algerian Ministry of Culture, and one of them was even leading a workshop on free expression. At the time, it seemed convincing evidence that cartoons were incapable of affecting society. Although the cartoonists’ monographs were on sale in the bookstore, freedom of expression was nil outside of the festival.4 Cultural events or publications can become a sanctioned space where dissent and criticism are permissible under state control, to a small, politically powerless audience—and even then criticism is allowed only up to a point.

Comics and cartoons in Egypt are indicative of a “speech bubble,” at once a political force with democratizing potential in a suffocated country and a forum for ideas in a realm separate from the highly regulated sphere of journalism. As for whether the speech bubble in comics will have a broader effect on politics and speech in the country, the best way to start such an inquiry is by looking at the newspapers.

How to Draw the President

President Sisi, humble and plain-faced, walks past his predecessors Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat. A corncob pipe dangling from his mouth, Sadat chuckles, “I wonder if he is really capable of lifting subsidies.”5 A brooding Nasser replies, “I wonder if he is really capable of achieving social justice.” In this cartoon, the once untouchable Sisi faces disapproval from the right and the left—and not from just any critics but from the two most symbolically weighty faces in the country.

Veteran cartoonist Amro Selim, in his typically sloppy hand, drew this for the September 6, 2016 edition of the privately owned Egyptian newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm. On the surface, it is a stinging critique of Sisi’s cutting of subsidies and his disinterest in the common man. Yet there are deeper meanings at play. To grasp the significance of two presidents laughing at the current leader, we first need to review Selim’s career and portfolio.

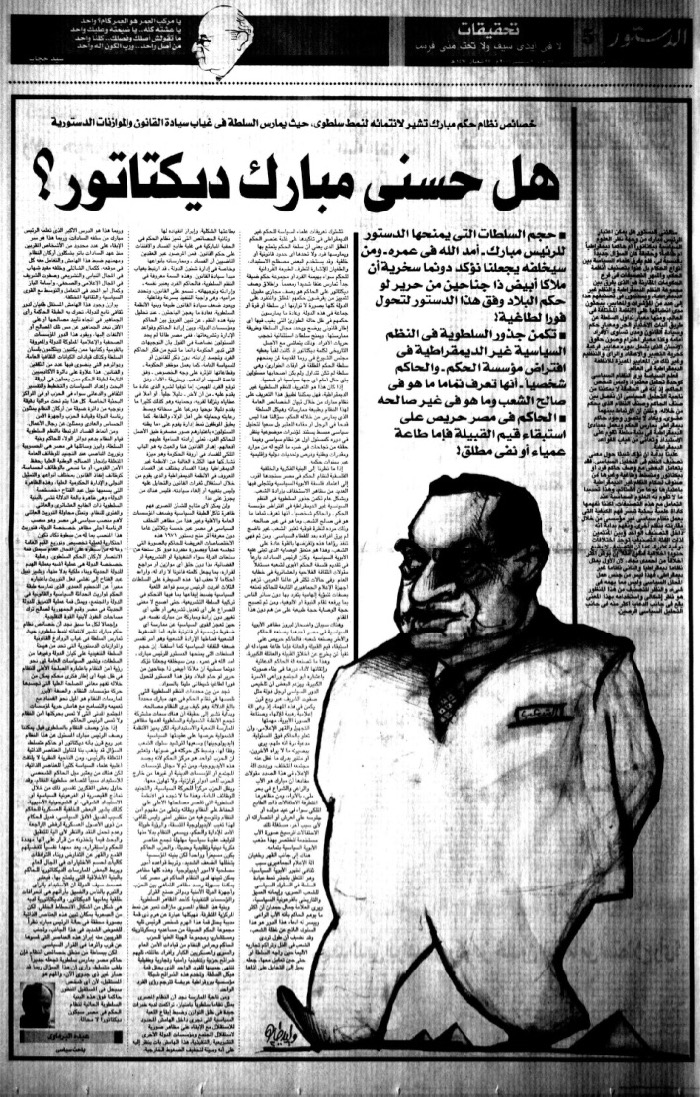

Selim, 54, is among the country’s most influential cartoonists. While heading up the caricature department of Ibrahim Eissa’s weekly newspaper Al-Dustour in the middle of this century’s first decade, Amro Selim was among the first cartoonists in Egypt to directly attack then-president Mubarak.6 A penal code regulation banned “insulting” the president, and at that time satirists tended to obey the regulation in their daily output. (Technically, “insults” to the president, as well as judiciary, military, and other state authorities, remain illegal, though the vagueness of the law—what constitutes an “insult”?—and the audacity of opposition illustrators means that the red line has always been blurry.) It took a clever humorist like Selim to work around the rule and play a trick on Mubarak. “For Al-Dustour, I started by drawing [Mubarak] from his back until people recognized it was him,” Selim recalled, sitting at his desk of sketches and cartoon books. “Then, I started [directly] drawing his face and his sons.”7 He galvanized his colleagues to also take the risk. In 2006, for instance, Walid Taher caricatured a particularly pugnacious and portly president accompanying an article headlined, “Is Hosni Mubarak a Dictator?”

This rabble-rousing approach to Mubarak created a dynamic space for experimental comic commentary. The format of Al-Dustour lent itself to creativity because cartoons played a central role in its layout and design. Up to eighty cartoons or comics appeared in each weekly edition. “Ibrahim Eissa wanted to make cartoons a main element of the newspaper, not just a column or corner,” Taher recalled.8 So Selim brought on board a stable of young illustrators, most of whom were virtually unknown at the time, to contribute to the broadsheet.9 “We were trying to create a new generation of cartoonists,” Selim explained. It is in this newsroom that the seeds of the current comic renaissance were planted. Key names in Egyptian cartooning arose from this moment at Al-Dustour, a group of artists who still affectionately call Selim “The General” for his role as mentor-in-chief.10

Selim was a bold watchdog during Mubarak’s twilight. But since the 2011 uprising, the cartoonist’s political outlook veered toward the mainstream. From 2012 to 2013, during the presidency of Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Morsi, Selim never pulled a punch in attacking the bungling Islamist in the privately owned daily Al-Shorouk. These visual assaults resulted in a barrage of death threats and lawsuits from Morsi supporters. Predictably, Selim celebrated Morsi’s ouster in July 2013, and given the intimidation he had faced during that difficult year, his initial enthusiasm was understandable. But virtually overnight after the coup that ended Egypt’s brief experiment with elected civilian rule, the great dissident Selim transformed, for a time, into a conformist—uncritically supporting the military, unleashing invective against the severely weakened Brotherhood, and cheering on the state’s indiscriminate crackdown. For more than two years, he never drew Sisi at all. When Selim did represent Sisi, he would insert a photograph of the former general, a suggestion that Sisi was unassailable and unsuitable for caricature. Selim’s unreflective deference for the new military regime was emblematic of the country’s tragic trajectory in the post-2013 period.

When I met with Selim in January 2015, the cartoonist asserted his affinity for Sisi. “The difference between the days of Mubarak or Mohamed Morsi and now is that we now have something we have never had before, at least since Nasser: a ruler that is loved by the people,” he told me.11

At that time, Selim expressed openness to other perspectives. As the new head of Al-Masry Al-Youm’s vibrant caricature department, he was proud to say that he had never rejected his colleagues’ cartoons, even when they featured the president’s mug or clashed with his political preferences. Selim’s colleagues agreed. “At the end, [Selim] is a cartoonist and he knows the value of free speech and he knows the value of publishing a cartoon even if it was holding or carrying counter political views, political views that he is against,” said Anwar,12 who draws a daily cartoon for the third page of Al-Masry Al-Youm. “Maybe we have different political views, but at the end, all of us are cartoonists.”13 And each of the five cartoonists on the Al-Masry Al-Youm team had a different approach to the ongoing political and economic imbroglio.

Only in November 2015 did Selim publish his first caricature of President Sisi, and it was rather critical. In the cartoon, a journalist sits at his desk and tries to write as Sisi sits cross-legged on his head. The president glumly frowns as he wobbles.14 This cartoon was indicative of a shift in Selim’s perspective. Occasionally, from 2013 to 2015, Selim had drawn silly gags about the pro-Sisi hysteria sweeping the country, but they were not as harsh as the image of Sisi literally weighing down on a newsman’s head.

This was a milestone for Selim, but that didn’t mean that he had taken to regularly lampooning the president. It is therefore notable that the next time he would caricature Sisi he would also draw Nasser and Sadat dressing him down.

When illustrated portraits of Nasser and Sadat appear in the Egyptian press, whether privately or publicly owned, they tend to be unquestionably laudatory, replete with self-evident messages of grandeur. Historically, both presidents had appeared on the cover of children’s magazines, such as the Arabic version of the Disney comic Miki (Mickey) and Samir, during their reigns—comics that serve as a sort of nationalist training ground for kids. Nasser and Sadat’s mugs occasionally appear in political caricature in the daily press, typically on national holidays, praising Sisi, or participating in other forms of hagiography. When Nasser has appeared in cartoons alongside Sisi, such as in the summer or fall of 2013, the Arab nationalist hero has praised his underling, saluting him or employing a nationalist slogan like “Bless your hands.”15 What a contrast to see the great Nasser questioning Sisi’s efficacy.

It is also important to consider how Selim rendered Sisi in his caricature. Though superficially respectful—as is often the case in radical web comics about the president that emphasize his baldness or stubbiness—there is also nothing exceptional or positive about Sisi. His suit, face, and hair are all simple. He is shorter than Nasser and Sadat, whereas in the nationalist iconography they are all depicted as being of similar heights with Nasser inching slightly above the others. In Selim’s illustration, Sisi also lacks the liveliness of Sadat or the masculine prowess of Nasser.

Selim’s cartoon is especially plucky in comparison to the glorious representations of Sisi as military victor, sex object, patriarch, and fearless leader—images that peaked in the 2013–14 period but continue to appear in the cartoons of the state-run newspapers like Al-Ahram and Al Akhbar, and on the covers of establishment magazines. The president is markedly different in this world of unmitigated nationalism, deified in posters and postcards of aviator-donning Sisi beside a ravenous lion, or on women’s underwear, or the infamous Sisi truffles (sweets that comedian Bassem Youssef famously sent up in an episode of his show, The Program). In Amro Selim’s pen, we see a humbler Sisi, the ghosts of the past questioning whether he is suited for the job. Furthermore, Mubarak and Morsi are missing. These ejected leaders, whom Selim frequently draws alongside one another behind bars, have been relegated to the dustbin of history.

In Amro Selim’s pen, we see a humbler Sisi, the ghosts of the past questioning whether he is suited for the job.

In the decade since he first drew Mubarak, Selim has edged toward the establishment, becoming a bellwether of mainstream Egyptian politics. And even his two caricatures of Sisi seem conservative when compared to the young gang of cartoonists he cultivated a decade earlier at Al-Dustour.

The Mad Cartoonists of Cairo

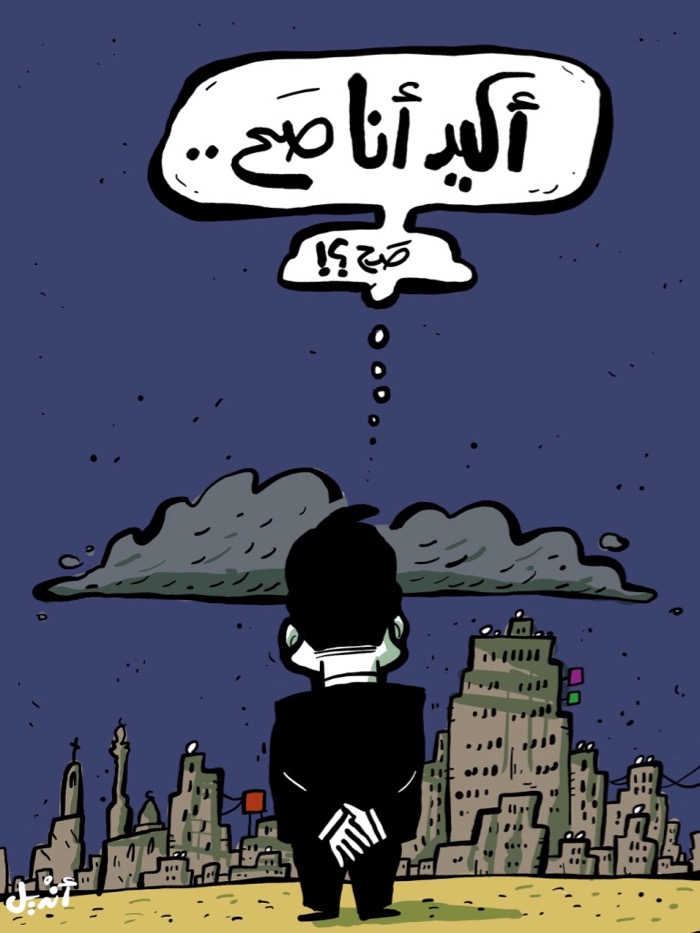

“I must be right … right?!” a pensive Sisi asks himself, facing a dust-brushed Cairo.

This cartoon, “Existential President,” is among the myriad disparagements of Sisi drawn by the Egyptian cartoonist Andeel.16 In another cartoon, a juvenile Sisi plays with a superman action figure and a toy bus. (“We love you Mr. President, seriously Mr. President, don’t be afraid Mr. President, beep, beep, vrrrrooom, vrrrrooom,” he babbles to himself.) In yet another, an oversized, smiling Sisi sits at a chaotic table of food and drink, a waterpipe strewn on the floor. (“Excuse me young man, who’s going to pay for all this mess?” the waiter whispers to another customer.) Other cartoons by Andeel employ symbolic violence against the president—showing him as a vengeful murderer gunning down a demonstrator or an aloof autocrat seeking admiration from his staffers, wholly ignorant of just how wrongheaded his policies are and how much citizens have come to dislike him.

To be sure, Andeel’s expressions of dissent are risky considering the multitude of forms that state-sponsored censorship has taken. To name but a few of the innumerable examples: in fall 2015, Andeel’s colleague from the news site Mada Masr, the investigative journalist Hossam Bahgat, was detained and interrogated; in May 2016, the five members of the satirical musical troupe Street Children were arrested for “insulting the president” in their web videos; in June 2016, authorities kidnapped and deported a Lebanese newscaster for being critical of the state. In addition to the banning of the Muslim Brotherhood, the secular April 6 Youth Movement and the soccer fan groups known as the Ultras have also been outlawed. In the meantime, the top editors of seventeen newspapers have pledged allegiance to Sisi.

In this stifled climate, Andeel has gone on to establish himself as an audacious critic of the regime. An apprentice of Amro Selim during the busy days of Al-Dustour, the thirty-year-old Andeel credits Selim with teaching him “how to have a political opinion at Al-Dustour.”17 Andeel’s work is defined by independence. Since the day of Morsi’s ouster in July 2013, he has drawn scathing criticisms of the military’s ascendency and impunity. Part of Andeel’s brashness relates to the possibility afforded by the medium in which he works: he publishes his cartoons online on the independent news outlet Mada Masr.

This cult of personality around Sisi—the fact that the former general was able to garner the full support of Amro Selim for two years—is one of the primary lines of inquiry in Andeel’s work. He is especially concerned with the reasons that citizens trust authority and how authority engages in indoctrination. “All these ideas that, for me, are a lot more important than saying Sisi is shit,” Andeel said. “I’m interested in why Sisi is shit, why do people not know or not realize that Sisi is shit…And to analyze all of that you have to go into much deeper human attributes to the story.”18 For that reason, his cartoons are as critical of the citizenry as they are of the boss.

His caricatures of Sisi, as a simply drawn weakling or as an angry monster, are only powerful in relation to the cultish caricatures of the president that appear in the mainstream and official media. Andeel’s jokes are funny because they swipe up against the unspeakable, like a GIF of Sisi wrecking a young boy’s sandcastle. Does Andeel’s graphic assault on authority suggest that cartoons are treated differently than other forms of media? Or is it that government haphazardly enforces the already vague red lines of society? Those are questions for political scientists. Andeel would rather discuss satire and aesthetics; he warns that readers shouldn’t exclusively see his work through the lens of censorship. “It’s true that censorship exists here,” he said. “I don’t think that’s the most important thing about my work.” He sees the most important aspects of his work to be the development of his aesthetic style, approach, and ongoing critiques of Egyptian society.

It should come as no surprise that Andeel is part of a core collective of artists who have provoked the development of comic art in Egypt. Together with political cartoonists and graphic artists, several of whom previously worked together as cartoonists for Al-Dustour, Andeel founded the zine Tok Tok on the eve of the 2011 uprising. Since its inception in early January of that year, Tok Tok has produced fourteen periodical issues and organized many events, each packed with a diversity of comic narratives and other illustrated forms (caricature, poetry, short stories with drawings) that capture aspects of Cairo often absent from the mainstream media.

Tok Tok is part of a new wave of comics across the Middle East, among them Samandal in Lebanon, Skef-Kef in Morocco, and Lab619 in Tunisia (new publications elsewhere continue to sprout up).19 Rather than collaborate with officialdom, these publications are finding ways to self-publish and have in turn created die-hard cult followings.20

Most of the tales in Tok Tok do not address high politics or policies, yet they rumble with political messages. Some examples include the depiction of poverty, questions about how technology envelops the quotidian, and the retelling of subversive narratives from the historical record. Sometimes straightforward editorial cartoons do figure in, like a classic centerfold by Andeel in which the president is dismissive of a yes man. (“Sir! Sir! What are we going to do with the trash, the traffic, electricity, hospitals, security, wages, judiciary, and the future? What will we do with all the ignorance?!” The president replies, “Increase ignorance.”)21

There are also experimentations in graphic narrative. In the fourth issue, Andeel illustrated the opening scene of Beer in the Snooker Club, Waguih Ghali’s 1964 novel that condemns the Free Officers’ Movement and Nasser’s widely revered nationalization project. Originally written in English, Snooker Club is a bildungsroman in which the beleaguered protagonist engages in antigovernment communist organizing in defiance of the authorities, though mostly he just drinks with his buddies, as the title suggests. Political cartoonist Makhlouf, 34, did something similar in a sixteen-page narrative for Tok Tok’s eighth issue by illustrating the Denshawai Incident from an Egyptian perspective. (In 1906, British officers on a pigeon-hunting escapade shot the wife of a local leader in the Egyptian village of Denshawai, and later fired on a mob of villagers, stirring an insurgency. Denshawai, having been recast by painters and poets over the century since it occurred, has become an emblem of revolutionary and anticolonial Egyptians.) Both Andeel and Makhlouf have unearthed overlooked antiestablishment narratives and packaged them in a form that millennials want to consume.

Another recurring theme in Tok Tok’s varied stories is that Cairo’s hidden underbelly is brought to the foreground. Within its issues, the burgeoning city is traversed by foot—its alleys are opened up, its stairwells climbed, its characters given space to discuss their anxieties. It’s fundamentally different from the traditional political cartooning in the Egyptian press, where the capital is represented by a structurally incorrect composite landscape of the pyramids, the Cairo Tower, a mosque, and a church all beside one another. Mohamed Shennawy, 38, a cofounder of Tok Tok and its art director, describes his personal style as “drawing the street,” an approach that permeates much of the narratives in the alternative zine.22 Even the publication’s namesake—Tok Tok—the Egyptian version of the three-wheeled motorized rickshaw, common in Cairo’s more impoverished districts, is an attempt to refocus attention on the marginal.

This recognition of Cairo’s blemishes is a distinctive part of the alternative comic artists’ approach to Cairo and is as significant of a development as satirical attacks on the president. In a sense, the two go hand in hand. Tok Tok might never have emerged if not for another comic with a vehicular name that irked the authorities, published in 2008: Metro by Magdy El-Shafee. Considered the first graphic novel published in Egypt, El-Shafee’s tale of a marginalized computer programmer driven to commit a bank robbery captured the desperation of youth in the middle of the century’s first decade. Each chapter focuses on a different Metro station, taking the reader to the city’s popular neighborhoods as well as dark corners of downtown. Authorities quickly banned this Cairo noir, and the prosecutor attempted to indict El-Shafee for “violating public morality.” A second edition of the Arabic comic only appeared again in Cairo in 2012, amid Morsi’s very incompetent year-long tenure. It has since been republished again and is more widely available in its third edition. That Metro was banned under Mubarak and has been reprinted under Sisi is indicative of the red lines’ fluidity. Generally speaking, Egyptian authorities haphazardly enforce the rules, if at all.

“In comics, you have to have a vision, a point of view, a perspective on life,” said El-Shafee, now 55.23 Having contributed to the newspaper Al-Dustour in the mid-aughts, he went on to produce three issues of the comic zine El Doshma from 2011 to 2012. El Doshma was a publication inspired by the visual culture of the revolution. It should come as no surprise that it was edited by the novelist and journalist Ahmed Naji, who was convicted in February 2016 of “harming public morality” for a fictional text in which he matter-of-factly describes sex acts and drug use (an appeals court issued an injunction for his release in December 2016, after serving ten months of the sentence in Tora Prison).24 Many political cartoonists addressed Naji’s sentencing in their cartoons, invoking punch lines that acknowledge the risks of contributing to the arts while ambiguous laws remain on the books.25

“In comics, you have to have a vision, a point of view, a perspective on life.”

El-Shafee and with Shennawy are the co-organizers of the Cairo Comix Festival, which convenes graphic innovators from across the Arab region for four days of seminars, panels, and trading of wares. In 2016, for Cairo Comix’s second edition, El-Shafee is particularly concerned with imparting storytelling skills to young cartoonists, many of whom, he notes, are already talented artists. “What we need now is to master graphic narration,” he said, explaining why he has invited top comic scholars from Europe and artists from across the Middle East and North Africa.26 El-Shafee is taking on the role of mentor to the emerging generation of comic artists.

By all accounts, Tok Tok has been a success. It won the first annual Comics Guardian Award from the newly established Mu’taz and Rada Sawwaf Arabic Comics Initiative at the American University of Beirut, and its cofounders have received invitations to key cultural gatherings in Europe. Comics scholars and top publications have cited their contributions to the art form on an international level.27 More crucially, even with its print run of five hundred to fifteen hundred copies per issue, Tok Tok has been influential in Cairo. New comic publications, like Garage and others, have emulated its form, as have several one-off comic projects in Cairo and Alexandria. A new foundation called Mazg has hosted comic workshops and events in its Tahrir Square office. Local publishers are increasingly interested in printing graphic novels in Arabic (although there are still relatively few on the market). And with hundreds of young fans showing up to each Tok Tok issue launch, soon the next generation of comic artists will be up to no good.

Cartooning the Party Line

A smug Sisi looks on, as a beaming Sadat rests a hand on his shoulder. Nasser smiles broadly and asks for a photo with him. Khedive Ismail congratulates Sisi on the New Suez Canal. A white-bearded Father Time opens a door labeled “history.”

This July 26, 2015 cartoon from Al Akhbar is typical of how the state-run newspapers depict presidents past and present. The cartoon has a transparent message, though the illustration itself ensures its own clarity by adding (unnecessary) labels for Ismail, Nasser, and Sadat. Labeling is an example of rhetorical saturation in pro-state advocacy, attempts to ensure clarity for the reader.

The illustrator, Amro Fahmy, draws social-realist caricature in service of the state. Fahmy has published more than ten books of milquetoast caricature, where he tends to take aim at characters like George W. Bush or more recently Barack Obama, while sparing leaders like Mubarak or Sisi of criticism. That his 2000 book 1/2 Dihka—which translates into English as “Half a Laugh”—was part of a book series promoted by former first lady Suzanne Mubarak, with her smiling photograph appearing on the back cover, is fitting. Fahmy’s oeuvre is the borderland where caricature becomes propaganda.

Although the cartoons of independent cartoonists sometimes contain straightforward political messages, the cartoons are distinguished by their whimsy and wit, the interplay between the written and visual. This means that the cartoons themselves are in dialogue with the reader, leaving blanks for the reader to fill in and thus to be a participant in the joke. Not so in the preponderance of cartoons in Egypt’s state-run media, which convey an uncritical earnestness about the state of affairs.

The dominant discourse surrounding the president, to this day, is that of support, if not oozing nationalism and love of patriarchy. In a full-page spread on Al Akhbar’s front page, Sisi grasps a giant steering wheel. He is a full head taller than the smattering of smiling adults and children who wave Egyptian flags behind him. A dove with an olive branch flies by and a crane operates in the distance, which taken together signal a glowing endorsement of the president’s 2015 expansion of the Suez Canal. Sisi is rendered quite realistically, more of a portrait than a caricature. (A similarly stoic Sisi has graced the cover of the children’s comic magazine Samir on several occasions.)

The cartoonist old guard continues to lionize the autocratic regime in their output for semiofficial newspapers as well as in salons and gallery openings cohosted by the Ministry of Culture. Any observer of contemporary Egypt recognizes that, for all the enthusiasm about street art and new experiments in visual culture, the central trend of the past five years has been a sycophantic status quo in which many media actors assert that the army and the police can do no wrong. In the realm of cartoons, this includes the persistent and uncritical support for state policies as well as tired tropes of a conspiratorial nature, namely anti-Americanism and anti-Zionism. (There are occasional bouts of anti-Semitism in the semiofficial press, although anecdotally this trend seems to have decreased since 2011.)

Xenophobia and conspiracy theories are commonplace in state-run broadsheets. For the flagship state newspaper Al-Ahram, Galal Omran drew Barack Obama as a Salafi with a long scraggly beard, short pants, and sandals. Obama, with derogatory features such as extra large ears and a toothy grin, holds up a four-finger salute—a Brotherhood sign of solidarity—though the grossly rendered president has long, claw-like fingernails. He stands beside a new American flag: two swords and a Quran, the Brotherhood’s symbol, have taken the place Old Glory’s fifty stars.28 Of course the assertions made in these cartoons are false. But Egypt’s state newspapers have rarely critically engaged with difficult events, let alone addressed them with nuance. There are scores of other outlandish examples. In December 2015, Al-Ahram published a cartoon, by Farag Hassan, in which the Statue of Liberty has sprouted a similar beard. The grotesque statue holds a bomb instead of a torch, and grips a book that says, “Renaissance,” an allusion to Morsi’s national project. In this fantasyland, Washington is the patron of the Muslim Brotherhood and more recently, the Islamic State.29

Such bizarre tropes are remarkable because they appear so infrequently in the cartoons of independent artists. The cartoonists of Al-Masry Al-Youm or other private outlets are censorious of the policies of Israel or the United States in their panels. However, they engage in satirical disparagement of Tel Aviv or Washington without reverting to bigoted stereotypes or ridiculous conspiracies.

The cartoonists of Al-Masry Al-Youm or other private outlets are censorious of the policies of Israel or the United States in their panels. However, they engage in satirical disparagement of Tel Aviv or Washington without reverting to bigoted stereotypes or ridiculous conspiracies.

In fact, these critical cartoonists sometimes make fun of the media for its trafficking in conspiracies. For instance, when the Egyptian military accidentally massacred a group of Mexican tourists in the Western Desert in September 2015, the cartoonist Anwar mocked the Egyptian media in his third-page frame for Al-Masry Al-Youm. In it, a newscaster exclaims, “In this episode we reveal—were the Mexican tourists part of a Zionist-Mason-American conspiracy against Egypt?!” One imagines that the cartoonists drawing for the state-run Egyptian media might answer in the affirmative.

Memes of Dissent

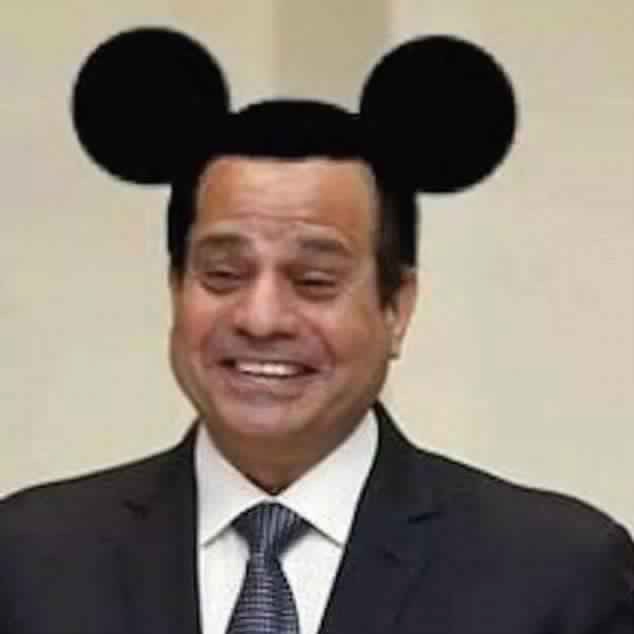

The smiling photograph of Sisi is crowned with Mickey Mouse ears.

That simple image packs a satirical punch, a broadside at a Mickey Mouse leader of a Mickey Mouse state. Amr Nohan, a twenty-two-year-old law graduate undergoing his compulsory military service, posted this Photoshopped gag on Facebook. He was indicted for “insulting” a national figure in August 2016 and sentenced that December to three years in prison. In his indictment, the military prosecutor claimed that Nohan possessed “thoughts inside of him that run contrary to that of the ruling regime.”30 Caricaturists and journalists have always faced this type of looming threat. Now citizens who share their political opinions online are also subject to state scrutiny.

Although the constitution adopted in 2014 protects freedom of speech, new regulations have come in the way of those rights.31 The government has tightened control of public spaces and platforms like Facebook and Twitter through a variety of legal tactics. A counterterrorism law, in particular its Article 33, contains language that stifles journalistic practice, notably in outlawing the dissemination of reportage that is at odds with the Defense Ministry’s official story. The government has also hired Western companies and software to surveil the Egyptian internet.32 A draft cybercrime bill, approved by the parliament in September and awaiting approval from the cabinet (the prime minister and the cabinet ministers), includes a number of worrying provisions. Chief among them is a three- to fifteen-year prison charge for “Setting up, administering or using a website, private account or information system with the aim of illegitimately trading ideas, drugs, arms and human organs, or the facilitation or advocacy of any of these forms of trade.” Surely cartoonists trade in ideas (less so the latter items) and the ambiguousness of an “illegitimate” idea is a cause for serious concern.33 There are a number of other technicalities of the bill under which online dissenters might be charged, even if their participation in such illegal behavior is unbeknownst to them (such as unwittingly visiting an illegal website).34 Of course, with so many penal code regulations that outlaw “insults” to various state institutions, the government scarcely needs more ammunition in its potential to crackdown on dissenters.

All of these pose risks to the country’s estimated forty-four million Facebook users and four million Twitter users who have come to see both spaces as relatively free compared to public forums and local media. Indeed, the state has aggressively gone after people for Facebook posts and tweets, making clear that in practice it’s just as risky to officially publish as it is to “say” anything in any public platform. Even as Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms have provided new opportunities for the spread of ideas, they are also dangerous spheres. Interest groups and state actors closely monitor these seemingly open spaces.

Online dissemination has blurred the line between consumers of satire and the satirists, which poses problems for just about everyone in the current repressive environment. In 2011, during the freewheeling revolutionary period after Mubarak’s ouster, business magnate Naguib Sawiris also had a Mickey Mouse problem. Sawiris tweeted an image of a bearded Mickey and a niqab-wearing Minnie, a jab about religion’s increasing invasion of public discourse.35 A group of Salafi lawyers sued Sawiris for blasphemy. The court later threw out that and another case against Sawiris for the tweet, but the thorny issues surrounding satire in the age of social media endure.36 (It should be noted that neither Facebook nor Twitter have instituted any protections for dissidents in Egypt, even while the Egyptian state continues to target online malcontents.) In the meantime, prosecution of so-called “blasphemers” and other forms of religiously inspired repression have continued full-bore under Sisi.

The five years since the uprising have, coincidentally, seen both comic production and dissemination shift toward digital. Today, most cartoonists draw on tablets, and social media has become the primary site of distribution. For veteran illustrators, digital production allows for new artistic styles, approaches, and complexities. It also lowers the barrier of entry for the untrained, which means that cartoonists now have to compete with meme-creators. The meme, it might be argued, is the political cartoon of the early twenty-first century.

The meme, it might be argued, is the political cartoon of the early twenty-first century.

In photoshopped images or comics, GIFs, or short videos, Egyptians are mashing up the day’s news with famous actors and iconic scenes from cinema, much in the same way that cartoonists do. Scholars recognize that memes represent an important cultural currency and a forum of satirical ingenuity.37 The most popular of these meme-sharing pages, the Asa7be Sarcasm Society, has more than thirteen million followers on Facebook (by contrast, Al-Ahram has about three million and Al-Masry Al-Youm about nine million). Memes have in fact become so popular that some cartoonists are creating meme-style cartoons, notably Osama Hajjaj of Jordan.

Meme culture means that Sisi’s visual gaffes—his looking up at the ceiling aloofly during a meeting at the 2016 UN General Assembly or staring out the window of an airplane knowingly as the Suez Canal is expanded below—result in a deluge of Photoshop jabs. Even if the mainstream Egyptian media is tempering its criticism of Sisi on that given day, there is always barb online.

Sharing cartoons and other visual commentary online creates new forums for discussion. Dozens of Egyptian and Arab cartoonists have embraced the opportunities of social media. This move to social media is beneficial not only for users, but also for cartoonists, who can directly connect with their readers. Andeel has described Facebook as a platform for a meeting of the minds, where he can get into the heads of his critics and of readers he might not necessarily relate to or meet in daily life. “When I’m making cartoons, when I’m expressing my opinions on Facebook or whatever, I’m always more concerned about people who totally disagree with me,” he said. “How can I talk with them rather than talking to people who already agree with me or already think I’m right?”38 Andeel’s take is an optimistic one. Expression online, however, is a space that is under risk.

Consider the case of Islam Gawish, 29, a producer of viral web comics on his page el-Warka, or “The Paper.” His jokes and jabs are of note not only because of their following of two million and counting; Gawish, through his experimentation with stick figures and use of acutely Egyptian satirical techniques (particularly burlesque and gallows humor), has innovated the web cartoon, always penned on notebook paper with simple doodles, along with punch lines in heavy slang.

On January 31, 2016, Gawish was due at the Cairo International Book Fair. At midday, police investigators burst into Gawish’s office and hauled him off to the station for questioning. Authorities released him the next day amid a torrent of international protest, and the president himself offered a testament to the provocative power of comics. “My God,” Sisi said on live TV, “I am not upset with Gawish or anyone else.” Sisi continued: “Every day, the ninety million people in Egypt find many things which make them uncomfortable, like the case of Gawish … Such things happen, and this is natural in a country which was in a revolutionary state for four years.”39

The most curious element of the case is that police detained Gawish overnight allegedly for “operating a Facebook page without a license.” He was released the next day without charge, but this seemed to be an unprecedented accusation because no web publisher in the country has acquired a license for a social media page. It is a worrying indicator of the security state’s toolkit of repressive tactics.

On February 2, Gawish wrote a long account of his arrest and release on Facebook, concluding on a note of defiance:

I will not stop drawing. And I will continue doing what I like and continue working in this direction. I am neither beating the drum for anyone, nor cursing anyone. And I have no biases toward anyone. I have my own opinions, whether intellectual or political. I am not extremist in my ideas and don’t claim to be a hero and a role model. Thank you all.40

The post received thirty-seven thousand likes, more than three thousand shares, and nearly two thousand comments. Sure, that’s a drop in the bucket in the broader internet ecosystem, but it is significant that a Facebook page founded in 2013 has swelled to over two million fans and remains active.

When I met Gawish, he didn’t want to get into the details of his arrest and preferred to discuss the incarceration of the novelist Ahmed Naji and the satirical troupe the Street Children. I asked Gawish about why cartoons are so powerful, and his answer was as simple as his stick figures: “People want to laugh.”41

Gawish has never caricatured the president himself, not because he quivers at authority but rather because he prefers to craft jokes that deal with social issues. He addresses politics on his own, sardonic terms. In a cartoon from November 10, 2015, a bald grownup speaks to four crudely drawn youths: “Who here born in the eighties or nineties needs a hug?” “All of us,” they respond.” In the next frame, the older man embraces them, saying, “Come here, come here.” In the final frame, the four youngsters find themselves in a cage, and the bald man smiles. This sort of black humor is typical of Gawish. The cartoon is also a reminder that Nohan, the conscript who posted the photo of Sisi with mouse ears, remains in prison—as do countless others.

Speech Bubbles

Dissent endures in Egypt’s independent broadsheets and online, in spite of the staying power of Sisi’s cult and the new and pending surveillance techniques employed by the state on social media. All the while, state newspapers and the Ministry of Culture sustain proregime cartoonists. The Mad Cartoonists of Cairo are using their pens to redraw the red lines of acceptable speech, and they often face resistance.

Looking at this spectrum, it is tempting to think that cartoons in the Egyptian media—and broadly in the Arab world—represent a microcosm of perspectives about public affairs. But even this claim would be a stretch, given the absence of an entire strand of perspectives, namely that of an Islamist persuasion. The Muslim Brotherhood did print amateurish cartoons in its newspaper, Hurriyya wa-‘Adalla, which was published daily until it abruptly ended in the aftermath of the 2013 coup. Its cartoons mirrored the qualities of earnestness and propaganda of cartoons in Al-Ahram and Al-Akhbar. Rather than critically engage the reader or question taboos, these status-quo cartoonists tend to offer steadfast support for policies or straightforward condemnation of out-groups. (In that sense, and unsurprisingly, the Islamist cartoons weren’t very funny.) So what then do cartoons and comics in Egypt represent? Are they simply a badly drawn caricature of a complex society?

Comics hold out subversive potential and are best suited for transmitting progressive perspectives through tales with hidden meanings or stories of marginalized characters. And because authorities or cultural figures have rarely taken comics seriously (as an artistic, literary, or political medium), they further hold the potential to carry radical politics. But at the end of the day, the field of cartooning is all about individuals—and individuals’ political preferences evolve over time. It is difficult to speak of movements, as cartooning is a solitary craft. And the hybrid art can just as easily convey conservative or revolutionary messages.

It is worth considering an idea put forward by George Khoury Jad, of Lebanon. In his column for An-Nahar about the 2015 Cairo Comix Festival, Jad explains that in the past few years Cairo had seized the comic mantle from Beirut. He is cautiously optimistic, expressing concern that state censorship might thwart the ongoing comic renaissance. Jad, himself a comic artist who innovated the form during the Lebanese Civil War, concludes with a hopeful question, “Aren’t comics by definition dreams that provoke reality?”42 Although comics exist in the fantastical realm of the fictionalized and exaggerated, he suggests that comics can agitate and affect reality.

Indeed, comic strips are among the most vibrant realms of speech in Egypt today. The necessarily coded language of political satire—a realm of mixed metaphors and local jokes articulated in deep slang—provides a cover for overt criticisms of the government. The dearth of other critical voices in the media makes the difficult work of Cairo’s cartoonists even more potent. And in spite of imminent and frightening legislation that will further limit the sphere of social media, cartoons are eminently shareable online; the classic medium of the one-frame comic continues to gain new currency in the era of social sharing.

Perhaps this entire story boils down to one small event—that as editor of Al-Dustour, Ibrahim Eissa sought to fill the pages of the broadsheet with cartoons. Yet that platform brought together a group of artists who, experimenting with content and form, have left an enduring mark on the public sphere. Today, the cartoonists themselves deserve full credit for proceeding with wit and originality in forging forward through the murk of surveillance and clampdown.

In Egypt and across the Arab region, cartoonists have created new spaces for expression, speech bubbles that continue to expand and spread. There is certainly a risk that as these bubbles grow larger, the artists themselves become so emboldened that they will garner the undue attention of authorities, resulting in their repression or suppression. But as we read the works of Cairo’s Mad Cartoonists, a different scenario seems more likely. The community of artists that gathered at Al-Dustour during Mubarak’s reign has gone on to publish radical drawings against all odds. Their perseverance in the face of repression is a bold illustration of dissent, one that might boil over and erupt into other politically contested realms.

About This Project

This policy report is part of “Arab Politics beyond the Uprisings: Experiments in an Era of Resurgent Authoritarianism,” a multi-year TCF project supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Studies in this series explore attempts to build institutions and ideologies during a period of resurgent authoritarianism, and at times amidst violent conflict and state collapse. The project documents some of the spaces where change is still emerging, as well as the dynamic forces arrayed against it. The collected essays will be published by TCF Press in June 2017.

Notes

- See, for instance, “Egypt: 7,400 Civilians Tried In Military Courts,” Human Rights Watch, April 13, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/04/13/egypt-7400-civilians-tried-military-courts; and “‘We Are in Tombs’: Abuses in Egypt’s Scorpion Prison,” Human Rights Watch, September 27, 2016,

https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/09/27/we-are-tombs/abuses-egypts-scorpion-prison. - “China, Egypt Imprison Record Numbers of Journalists,” Committee to Protect Journalists, December 15, 2015, https://cpj.org/reports/2015/12/china-egypt-imprison-record-numbers-of-journalists-jail.php.

- Scholars are increasingly articulating the problems of the “hydraulic model” of humor, better known as the safety valve. See Anny Gaul, “Egypt, Laughter, and the History of Emotions,” The History of Emotions Blog, March 7, 2016, https://emotionsblog.history.qmul.ac.uk/2016/03/egypt-laughter-and-the-history-of-emotions/.

- Jonathan Guyer, “Speech Bubble: A Comic Festival in Algiers,” Institute of Current World Affairs, November 12, 2015, http://www.icwa.org/speech-bubble-a-comic-festival-in-algiers/.

- Sadat’s comment in the cartoon is a jab at the fact that during his presidency he attempted to severely cut subsidies, but was forced to reverse course following significant protests.

- Eissa went on to establish Al-Tahrir newspaper in 2011 and then Al-Maqal in 2015. He is a complicated and controversial character in the Egyptian media, though there is not space for further scrutiny of him here. See for example Heba Afify, “Ibrahim Eissa Is ‘The Boss,’ but at What Cost?,” Mada Masr, April 28, 2014, http://www.madamasr.com/sections/politics/ibrahim-eissa-%E2%80%9C-boss%E2%80%9D-what-cost.

- Amro Selim, interview with the author, Cairo, April 3, 2013.

- Walid Taher, interview with the author, Cairo, May 28, 2013.

- Among that cohort are cartoonists who have gone on to be hugely successful in Egypt, namely: Andeel, Abdallah, Doaa el-Adl, Makhlouf, and Hany Shams. Other now well-known artists, like Magdy El-Shafee and Walid Taher, were also contributors.

- Selim, interview.

- Jonathan Guyer, “Four Years after Tahrir, Egyptian Cartoonists Face New Challenges,” The National, February 28, 2015, http://www.thenational.ae/opinion/comment/four-years-after-tahrir-egypts-comics-face-new-challenges.

- Following a tradition in Egyptian editorial cartooning and like many of the cartoonists in this story, Anwar uses just one name professionally.

- Anwar, interview with the author, Cairo, February 24, 2016.

- Jonathan Guyer, “A Headstrong Caricature,” Oum Cartoon, November 5, 2016, http://oumcartoon.tumblr.com/post/132596864826/headstrong-caricature-selim-cartoons-sisi-egypt.

- See for example Jonathan Guyer, “Gallows Humor: Political Satire in Sisi’s Egypt,” Guernica, May 15, 2014, https://www.guernicamag.com/features/gallows-humor-political-satire-in-sisis-egypt/.

- For Andeel’s cartoons and writing on Mada Masr, see: http://www.madamasr.com/en/contributor/andeel/. Also see Laura C. Dean’s report, which discusses the history of Mada Masr in depth.

- Andeel, interview with the author, Cairo, June 21, 2015.

- Andeel, interview with the author, Cairo, Sept 29, 2015.

- Each of these publications boasts social media pages, but their primary product is old-fashioned: a print periodical that is usually on sale at booksellers and art spaces.

- Through their own ingenuity and limited grants from international bodies, such as foreign cultural institutes or the European Union, comic artists have been able to establish and print independent publications, and in turn have secured a semblance of autonomy—until the funding runs out.

- Jonathan Guyer, “Mad Magazines: Underground Comics Come to Egypt,” Harper’s Magazine, 332, Iss. 1990 (2016): 46–47.

- Jonathan Guyer, “Shennawy’s True Colors,” Oum Cartoon, June 1, 2016, http://oumcartoon.tumblr.com/post/145264113006/shennawys-true-colors-a-recent-trend-among.

- Magdy El-Shafee, interview with the author, Cairo, September 5, 2016.

- Ahmed Naji, interview with the author, Cairo, December 21, 2015.

- I gathered some of these in my blog post on A Day of Blogging for Ahmed Naji. See “Cartoons for Ahmed Naji,” Oum Cartoon, May 16, 2016, http://oumcartoon.tumblr.com/post/144456483286/cartoons-for-ahmed-naji-i-first-met-the-novelist.

- El-Shafee, interview.

- See for example Paul Gravett, Comics Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 73–74.

- Jonathan Guyer, “Cartoons as Black Mirror,” Oum Cartoon, February 28, 2015,

http://oumcartoon.tumblr.com/post/112302716146/cartoons-as-black-mirror-in-todays-the-national. - Michael Wahid Hanna and Daniel Benaim, “How Do Trump’s Conspiracy Theories Go Over in the Middle East? Dangerously,” New York Times, August 16, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/17/opinion/how-do-trumps-conspiracy-theories-go-over-in-the-middle-east-dangerously.html

- Farid Y. Farid, “A Pair of Mickey Mouse Ears Helped Earn This Man Three Years in Jail,” BuzzFeed, December 19, 2015, https://www.buzzfeed.com/faridyfarid/a-pair-of-mickey-mouse-ears-helped-earn-this-man-three-years.

- Article 65 of the 2014 Constitution reads: “All individuals have the right to express their opinion through speech, writing, imagery, or any other means of expression and publication.” Translation from: Gamal Eid, Karim Abdelrady, Mohammed Al-Taher, and Abdou Abdelaziz, “#Turn_around_and_Go_back: Internet in the Arab World,” Arab Network for Human Rights Information, May 2015, 77. Available online at: http://anhri.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/turnaround_and_gobackfinal-1-Autosaved.pdf.

- Sam Kimball. “After Arab Spring, Surveillance in Egypt Intensifies,” The Intercept, March 9, 2015, https://theintercept.com/2015/03/09/arab-spring-surveillance-egypt-intensifies/.

- Mohamed Hamama, “Egypt’s New Cybercrime Bill Could Send You to Prison,” Mada Masr, trans. Aida Seif al-Dawla, October 12, 2016, http://www.madamasr.com/sections/politics/how-new-cyber-crime-law-can-send-you-prison.

- For an in-depth reading of the controversial law, see: Mohamed Abdelaal, “Egypt’s New Cybercrime Law: Another Legislative Failure,” The Jurist, July 9, 2016, http://www.jurist.org/forum/2016/07/mohamed-abdelaal-egypt-cybercrime.php.

- Gus Lubin, “Telecom Mogul Naguib Sawiris Faces Death Threats after Tweeting This Picture of Mickey and Minnie Mouse,” Business Insider, June 28, 2011, http://www.businessinsider.com/bearded-mickey-and-minnie-mouse-2011-6.

- Associated Press, “Egypt Court Rejects Second Bearded Mickey Cartoon Lawsuit,” USA Today, March 3, 2012, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/story/2012-03-03/Egypt-Bearded-Mickey/53348284/1.

- See for example Adel Iskander, “The Meme-ing of Revolution: Creativity, Folklore, and the Dislocation of Power in Egypt,” Jadaliyya, September 5, 2014, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/19122/the-meme-ing-of-revolution_creativity-folklore-and.

- Andeel, interview with the author, Cairo, January 13, 2015.

- Jonathan Guyer, “The Pen, the Paper, and the President,” Institute of Current World Affairs, March 7, 2016, http://www.icwa.org/the-paper-the-pen-and-the-president/.

- Post on the Facebook page of Islam Gawish, February 2, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/Gawish.Elwarka/posts/1499538566736499.

- Islam Gawish, interview with the author, Cairo, July 28, 2016.

- George Khoury Jad, “In Focus: “Cairo Comix” Reclaims Its Role from Beirut and Launches a Movement of Change” (Arabic, title translated by author), An-Nahar, October 17, 2015. http://newspaper.annahar.com/article/276214-تحت-الضوء–كايرو-كوميكس-يستعيد-الدور-من-القاهرة-إلى-بيروت-ويطلق-حركة-التغيير