July 2016

Istanbul: Outside of the office of Evrensel, the socialist newspaper, in the historic neighborhood of Fatih, a group of young journalists, some in Star Wars T-shirts and all wearing sneakers, take a cigarette break. Near them, dozens of elderly men drink tea and smoke on low stools, their street café facing walls plastered with posters criticizing President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his AK party.

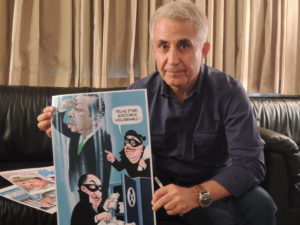

The cartoonist Sefer Selvi comes to greet me. We walk past the security guard and downstairs, through a room of 20-year-olds on computers, and then into a bare studio with mustard walls. An assistant brings us tea. Selvi has closely cropped gray hair and a short graying beard. He appears to be the oldest guy in what feels like the Turkish BuzzFeed. He is also one of the paper’s most radical voices.

In 2003, during Erdogan’s first year as prime minister, Selvi drew him as a horse being  jockeyed by an adviser. Selvi was sued and convicted of insulting a public official, though the charges were ultimately dropped. Thirteen years later, when I contacted Selvi in June, he was meeting with a prosecutor about another lawsuit; this one was against his colleagues at the satirical weekly LeMan, whose recent cover had allegedly injured now-President (and still sensitive) Erdogan. Un-phased, Selvi told me that has faced so many lawsuits for caricatures that he had lost count. “Humor does not mesh with rightism; it is exactly the opposite,” Selvi told me. “Humor criticizes. It does not obey; it reacts.”

jockeyed by an adviser. Selvi was sued and convicted of insulting a public official, though the charges were ultimately dropped. Thirteen years later, when I contacted Selvi in June, he was meeting with a prosecutor about another lawsuit; this one was against his colleagues at the satirical weekly LeMan, whose recent cover had allegedly injured now-President (and still sensitive) Erdogan. Un-phased, Selvi told me that has faced so many lawsuits for caricatures that he had lost count. “Humor does not mesh with rightism; it is exactly the opposite,” Selvi told me. “Humor criticizes. It does not obey; it reacts.”

A government crackdown on the media following the July 15 coup attempt has exacerbated the risks for Turkish humorists. Yet even before the clumsy military uprising and ensuing government crusade against dissent, the state of affairs was dire. In 2016, being a cartoonist in Turkey has been more difficult than ever. State prosecutors and Erdogan loyalists have used the crime of “insulting the president” to muzzle critics. Over 1,500 people—including cartoonists, celebrities, journalists, private citizens, and even a German comedian (in a case launched in Germany) — are under investigation or prosecution. In spite of the pressures, Selvi and his colleagues continue to caricature Erdogan and his ilk with impunity.

Legal threats have failed to upend Turkey’s long history of mocking politicians because Turkey’s cartoonists feel a deep obligation to castigate the powerful. “In these circumstances for a critic to remain silent would be unheard of,” said Musa Kart, a veteran caricaturist for Cumhuriyet, a Kemalist daily, who has battled several high-profile lawsuits for caricaturing Erdogan as a kitten and as a bank-robber. “From the perspective of the West, [the legal attacks] are something comical and absurd. But here it is not abnormal. There is no serious journalist or cartoonist who doesn’t have a case against him.”

The long tradition of dissenting cartoonists seems to be matched by an equally long tradition of clampdowns. A week before the coup, I asked Selvi if he saw similarities between cartooning today and the crackdown that followed the 1980 coup, in which the military shuttered many publications and rooted out opposition voices. “I was waiting for a question like that,” Selvi replied, smiling. “When you look at things from the humorist’s perspective, today there is incomparably more pressure… A few of us in the country are—despite everything—trying to work. But a bunch of people are scared or getting frightened.”

The pressures facing cartoonists also come in the form of the tragic events that they confront through their work, including the looming threat of a random attack. It is disheartening and depressing to draw about the seven major terrorist attacks that have occurred since October 2015, which have killed over 200 people in Istanbul and Ankara. It is also a strain to put forth original perspectives, as tragedy seems to repeat itself. Turkey’s conflicts become difficult to draw about without falling into cynicism.

All of these threads—the shrinking space for criticism and the stresses of persisting in good humor amid violent conflict—came together in the aftermath of the July 15 coup.

Two days later, Selvi caricatured the president as a simpleton, talking to a mass of exuberant supporters. “We want the death penalty,” chants the crowd, mirroring the president’s call to reinstate a policy of executions to punish the coup planners. “That’s the kind of democratic request I want from you,” says Erdogan.

The risk of publishing such a dark punch line even a month or a year prior would have been significant. Now, during an authoritarian crackdown in which thousands have been arrested, it seemed downright careless. And yet when I asked Selvi about what it meant to cartoon a crisis, he spoke matter-of-factly about his duty: “A cartoon is there… to evaluate the day’s events.” Implementing that logic, Selvi’s evaluation of the post-coup environment is scathing — and courageous.

* * *

Turkey boasts one of the richest and most advanced comic art scenes in the world. (Japan and the U.S. are probably the only more robust.) At nearly every newsstand in Istanbul and across the country, a dozen or so alt-comic weeklies are available as well as other cultural publications chockfull of illustrations. Their expressions of dissent are sometimes bolder than even the most radical opposition newspapers.

Every cartoonist I interviewed told me that the circumstances today were worse than any time in recent memory. This is quite an indictment of the present considering the many instances of comic censorship in Turkey’s not-so-distant history.

Turkish comic artists also faced challenges decades ago, especially after (successful) military coups. In 1971, following a government overthrow, authorities tortured the political cartoonist Turhan Selçuk and his brother, the newspaper editor Ilhan Selçuk. After the 1980 coup, authorities shut down the notorious comic magazine GirGir, a predecessor to contemporary satirical weeklies. At the time GirGir had a circulation of about 500,000. The reason for the closure: “allegedly mocking Turkish national identity with a cartoon of the Turkish flag on the naked body of a popular singer,” according to scholar Asli Tunç. A month later, however, GirGir, was up and running, lampooning the military government and its overreach. Sefer Selvi and Tuncay Akgün, an editor and co-founder of the comic magazine LeMan, were both among GirGir’s emerging artists during this period.

“[The military] crushed the opposition in the coup. We drew very radical things in reaction to this new situation,” said Akgün of the early 1980’s. “We were the only ones doing anything opposing the war in the southeast. Because of that [we faced] legal case[s] for insulting the army, insulting Turkishness, insulting religion, insulting Ataturk—everything, because we were dealing with everything, with all taboos.” For a decade, Akgün lived on the lam, running from the authorities, after he was sentenced for one of those so-called offensive comics.

There were a handful of legal attacks in the 1990s against cartoonists. In the wake of Erdogan’s inauguration as prime minister in 2003, the pressure has mounted. “The people in power now really don’t like cartooning and criticism,” said Musa Kart, whose has seen lawsuits proliferate since he was first sued in 2004 for drawing Erdogan and then again in 2014. “They are managing people though fear.”

Opponents have also violently intimidated cartoonists. Arsonists struck the offices of the comic weekly Penguen in May 2012. The legendary cartoonist Metin Ustundag and a staffer narrowly escaped the blaze. (Luckily there were only two people in the building at the time, as that week’s issue had just been put to bed.) The attack is also reminiscent of the 1993 massacre in the central Turkish city of Sivas, in which an arson attack killed 35, including intellectuals of the minority Alevi group, among them poets and artists. “The savage killing—the burning of people who had committed no crime—is unbelievable,” said Selvi, who is from Sivas, of the massacre.

Like other cartoonists I spoke to, Selvi recalled that many times over the years he has seen “shadowy men” waiting for him and his colleagues outside of the office, “stealthily taking our photos.” He acknowledges threats on social media or by phone or mail, mostly from Turkish nationalists or racists, not from yet from ISIS supporters. And yet throughout our discussion, he would casually laugh and downplay the threats. “Maybe if we lived in Europe or Hawaii our work would be much easier.”

* * *

On Tuesday, June 28, at around 10pm, terror struck Ataturk Airport. At my rental apartment in Istanbul, every noise caused me the jitters. The sirens in the background of Al Jazeera’s nonstop coverage made it sound as if the emergency were unfolding downstairs. Motorcycles bellowed down street below. The street dogs of the neighborhood seemed to be barking louder than usual. I got up to double lock the door.

Yet the attack on the airport did not ground activity in Istanbul—or even the airport. The next day, I met with two cartoonists: neither meeting was cancelled. In these discussions, and in other interviews, I asked a question that I have often posed to artists, illustrators, and satirists across the Middle East, Europe, and North America: How does a cartoonist react to crisis? The assault on the airport and the June 7 bombing in the historical district of Sultanahmet offered grim case studies of how satirical art reacts to deadly conflict.

“If… a tragedy happens, we have to do a cartoon about that, too,” said M.K. Perker, a versatile illustrator who has drawn for top American comic imprints and news magazines, as well as Turkish comic weeklies. Sitting in his office at Karakarga, a monthly cultural magazine he had founded earlier this year, he pulled up the cartoon he had drawn in response to the attack on the airport the night before. A family stands in line at the airport. “We thought we were going for summer vacation and it turned out to be a summer of mourning,” says the father in Turkish, a pun as the word “mourning” and “summer” sound similar in Turkish.

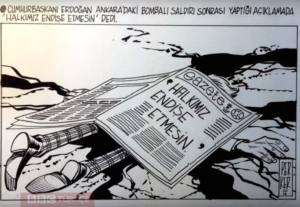

Perker tried to show me a cartoon he drew for BBC Turkish last October, after the double bombing in Ankara that killed 33 at a pro-democracy demonstration. But, as it often does in the wake of a crisis, the government had slowed the internet to the point of inaccessibility. (Facebook and Twitter are also down.)

The cartoon Perker wanted to show me depicts a dead man on the ground with a newspaper covering his severed body. The top caption refers to a statement made by President Erdogan after the attack, “Our people should not worry,” referring to the fact that the attack targeted anti-government activists, suggesting that the AKP’s right-wing supporters needn’t be concerned. But the newspaper on the dead man reads:

“Our people should not worry,” suggesting that each and every Turk is at risk because of the government’s negligence.

The cartoonist’s role is intimately tied to local conditions and traditions. It might seem surprising that Egyptian cartoonists frequently crack jokes amid and about tragedy. Just a day after the disappearance of EgyptAir 804 in May, an Egyptian cartoonist published a silly gag in the local paper. In it, one pilot screams out the window of his plane to anther pilot flying in the opposite direction, as if they were taxi drivers in downtown Cairo: “Turn and go back—the guy who is hijacking planes is waiting there!” Even the cartoon’s aesthetic style—round, toy-like airplanes and simplistic caricatures of pilots—was irreverent. Satirists likewise reacted with quick punch lines when a disgruntled man skyjacked an EgyptAir plane to Cyprus  earlier in March and when the Egyptian military massacred a group of Mexican tourists in November 2015.

earlier in March and when the Egyptian military massacred a group of Mexican tourists in November 2015.

This brand of black humor, unseemly to many Western audiences, is not mean-spirited. Having watched cartoonists in Egypt cut close to the bone with their satirical responses, I realize that such satire is not necessarily employed to shock or provoke. Black humor can be a method to work through tragic circumstances, to address them and elaborate on them, while providing a substantive critique of the status quo.

“In the West, cartoonists always try to make fun of funny situations or weird situations; they do cartoons to make you laugh,” said Perker, wearing skinny tie and freshly pressed white shirt, going through his pack of Marlboro Reds like candy. “We make cartoons to make you feel something,” he tells me, his voice the low drawl of a heavy metal singer.

And often humor is the most effective approach to elicit reflection.

And often humor is the most effective approach to elicit reflection.

After the airport attack, Sefer Selvi drew a suit’s hand patting a grotesque, bearded bomber on the back. Then an explosion booms. “Ah!” exclaims the suit in the next frame: he has lost his forearm, and the ground is covered in carnage. Selvi plays on the allegation that the AKP government, tacitly or worse, backs certain terrorist groups. Local journalists have levied this accusation, and some have gone as far as saying that Erdogan has provided support for the Islamic State to counterbalance Kurdish forces in Syria and Iraq. “[The cartoon] followed the logic,” Selvi said.

I ask Selvi about what is unique about cartooning in Turkey. “You live through massacres, you experience very painful events. So I think that intentionally or not we are a bit harsher in the things that we draw.”

* * *

On July 15, at around 10pm, another type of terror struck Turkey. This time, it came from a rogue group within the military, which launched a failed coup against Erdogan. That night, nearly 300 people were killed across the country.

It occurred on a Friday, and I was curious to see how Istanbul’s comic artists would react to the crisis.

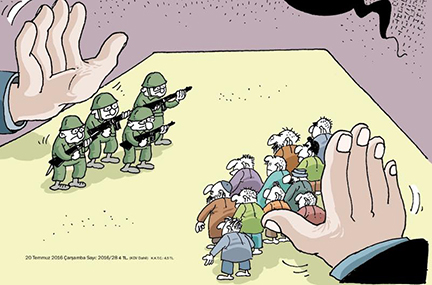

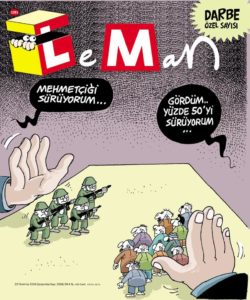

On the evening of July 19, LeMan, posted the cover of its “Special Coup Issue” online. “I bet on the soldiers,” says the man who pushes timid military men, as if they were poker chips, toward confrontation. Another man in a suit edges a handful of angry citizens toward the uniformed pawns, saying, “Good, then I’ll put my fifty percent on the people.” That’s a reference to Erdogan’s remark during the 2013 Gezi protests, in which he cited the AK Party’s electoral mandate (50 percent in the 2011 balloting) amid street demonstrations against his authoritarian policies. LeMan not so subtly suggests that the hidden hands of Erdogan’s regime are responsible for the bloody events of the coup or that a higher power created the conspiracy.

Hours later, the ultra-conservative, pro-Erdogan newspaper Yeni Şafak posted an article calling the cover disgraceful and saying that LeMan had made “a mockery of the martyrs” who died during the coup. On social media, intimidation swelled and trolls were disseminating LeMan’s address. At about 4AM, police went to their office, arriving just in time to turn away an angry mob. Police also stopped the coup edition of LeMan from being printing.

Despite the government’s convulsive response, it is unlikely that the censorship of LeMan will deter Turkey’s clique of opposition cartoonists. The possibility of a violent attack on a comic publication is real, but not foremost on any illustrator’s mind. “How can we protect ourselves?” asked Tuncay Akgün of LeMan, when we met in late June, at the publication’s offices. “These men enter the airport, they might enter parliament; they might enter anywhere and blow themselves up.”

I asked him if LeMan’s drawings of Erdogan would subsist as the lawsuit against them proceeds, and his response was flippant as Bart Simpson. “What else would we draw?”

We sat together at a booth at LeMan Café, a franchise downstairs from its studios, with walls saturated with cartoons and comics, some featuring nudes or caricatures of politicians. On the wall beside us was a tribute to the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists who were assassinated in the January 2015 attack in Paris. Leman has a sister-publication relationship with Charlie Hebdo, and slain illustrators Cabu, Charb, and Wolinski were close friends of Akgün. In fact, he was visiting Paris at the time of the attack. “I entered into a very heavy shock. I felt a lot of pain,” he recalled. During the interview—in the middle of the afternoon during the holy month of Ramadan—the café received a delivery of six crates of local beer and three kegs, a small, cheeky tribute to the deaths of his colleagues.

Akgün and his colleagues are also emboldened by the experience of GirGir’s in the aftermath of the 1980 coup and by the memory of their Parisian counterparts. “We have continued the tradition,” Akgün told me. “In fear, one cannot make cartoons,” Akgün told me. And the cartoonists I met in Turkey don’t seem to fear anything.

* * *

Selvi, himself a regular contributor to LeMan, remains defiant. His July 16 cartoon, the first one he published after the coup, went straight to the (president’s) guttural: Erdogan, big lipped and bug-eyed, says, “I am calling you to go into the squares to take ownership of democracy,” says Erdogan, addressing a group of workers, a reference to his call the previous night for Turks to go to the streets to support him.

“Alright, can we also go to Taksim?” asks a worker, speaking of Istanbul’s central square.

“Of course, you can go to Taksim,” Erdogan replies.

“Can we also go to Taksim on May 1?” asks the same worker, referencing the long history of authorities suppression of May Day protests in the city’s main square.

of authorities suppression of May Day protests in the city’s main square.

“Look, that’s FORBIDDEN!”

The soft-spoken Selvi had published another daring condemnation of the all-powerful president. “The road we are going down is a direct road to dictatorship,” he had told me. “For some friends, whether they like it or not, Erdogan and also the military and the police are red lines. But I’m the opposite; because these things are actually the source of problems for me. They are my green line. I draw them.”