SEOUL — “I never intended to make a school,” Oh Yeon-ho told me at his office in Seogyo, a trendy neighborhood in the western part of the capital. “I’m not an educator. I had no money to fund this kind of school. I’m just a journalist.”

Oh is best known in South Korea as the founder of OhMyNews, a progressive citizen journalist-run news outlet. But we met to discuss a lesser-known project: Ggeumtle Efterskole, a gap-year program on Ganghwa Island, roughly 20 miles west of Seoul, that is subject of a new OhMyNews documentary, “It’s Okay, Alice,” set to premiere in the second half of 2024.

At Ggeumtle, middle schoolers take one year to focus on rest, self-reflection and personal development while taking classes on music, arts and sports rather than more traditional subjects like math and history.

Such an extended break is unusual and even radical in South Korea. For most students, entering middle school marks the beginning of a six-year marathon they hope ends with a high score on the all-important college admissions exam and acceptance to a top university. As discussed in my last dispatch, that means most teenagers end up spending hours on extra classes and solo study, leaving very little time for leisure, friendship or play. Many point to the education system as a major cause of the high rates of anxiety and depression among South Korean young people.

It was the culture of competition, stress and unhappiness that Oh hoped to address in 2013, when he visited Denmark—famously one of the happiest countries in the world—for the first time. After interviewing dozens of Danish scholars, public officials and other experts, he concluded that Danish people are happier because of the values instilled in them by the education system, including freedom, self-love and collaboration. He was particularly inspired by efterskoler and folk high schools, uniquely Danish educational institutions that focus on students’ personal development as enlightened citizens.

“When I saw the faces of the high school students [in Denmark], they had the look of elementary school children—smiling and vivid,” Oh told me. “In South Korea, maybe younger students still have that smiling face, but once they go to middle school and high school, [their expressions] get darker and darker.”

Oh is has a kind and inquisitive demeanor, and seemed at ease when we met in OhMyNews’ office, a two-level, family-style house tucked behind tall buildings in Seogyo. After taking a seat together at a dining room table, Oh he peppered me with questions about my background in journalism while making me a cup of strong, hand-drip coffee.

Oh told me he had opened Ggeumtle Efterskole in 2016 hoping to enable South Korean children to prioritize happiness and health in their own lives—and that their experiences would inspire broader cultural change.

Although many I’ve spoken to in South Korea are critical of the education system and the pressure it puts on young people, few have expressed any hope that its fundamental problems can be adequately addressed by government reforms. As long as the cultural values that incentivize competition remain, I’ve been told, parents will continue to send their children to extra classes, students will continue to compete with peers and nothing is likely to change.

With Ggeumtle Efterskole and related projects, Oh has taken on the challenge of changing those values by offering four suggestions for healthy living: take control over your own life; love yourself; love others; and remember that life is worth living.

“I want to be happy right now, not only in the future,” Yeoreum, a student who features prominently in the new documentary, told me during an interview. “In middle school, I didn’t have any time to think about myself or my life, but I can think about those things at Ggeumtle.”

I spoke to Yeoreum on a cold day in mid-December while visiting the school’s campus, perched on a small hill between stretches of farmland on Ganghwa Island. Yeoreum, 16, is tall and reserved, and seems mature for her age. The two of us, several teachers and another student named Haru were sitting on cushions around a low table in the principal’s office, enjoying the heated ondol floor over mugs of tea. The room, like much of Ggeumtle, was covered with knickknacks and mementos, photos and students’ art, and when the principal’s snores interrupted our conversation—he was taking a post-lunch nap just behind a partition wall—I felt as though I were popping in to visit a neighboring family over the holidays.

Yeoreum used to be a high-achieving middle school student, she tells me. For years, she constantly studied to keep her grades high, working even longer hours than her peers, until one day, she hit a wall and could not study any more.

Openly discussing mental health challenges is uncommon in South Korea, and at first her parents couldn’t understand what she was going through. After consulting with doctors, they decided to send her to Ggeumtle, where, Yeoreum says, they all learned a lot about mental health and have come to accept her for who she is.

“I didn’t know before but I realized that freedom is really important for me,” Yeoreum told me in a mix of English and Korean. One of her favorite memories at the school was the simple act of catching sight of a star-filled night sky with friends and ending up stargazing. “Before that, I couldn’t do things I really wanted to do if I hadn’t planned for it because there was always something more important to do: studying,” she said. “But I really like spontaneously doing what I want to do. It’s the first time I’ve been able to experience that.”

The documentary “It’s Okay, Alice” shares the stories of other students who say they left Ggeumtle with healthier relationships with themselves and their parents. The filmmakers themselves and viewers also say it’s been transformative.

“While shooting the documentary I learned a lot, too,” the documentary’s director Yang Ji-hye told me at a coffee shop in Seogyo. She said she was born in Korea and completed all her schooling there, and although she recognized the problems with the education system, at some point, she “just got used to living in Korea.”

“I started to ask myself, ‘When I was a student, why didn’t I take the time to think about what might make me happy? And why did I not think about giving that kind of time to my two sons?’” Yang said.

That kind of epiphany is exactly what Oh said he hopes his works—Ggeumtle Efterskole, his books, lecture series and other educational programs—would inspire. However, others have told me that even once if the new values like Oh’s are in placehe advocates become widespread, acting in accordance with them may still present a challenge for many parents and students.

Ji Young Lee, a researcher in child psychology and education at Temple University, shed some light on the difficulties during a conversation about the playful learning model, a pedagogical framework that emphasizes the importance of guided play in children’s education.

Playful learning has significant benefits for children’s mental health and actually improves their long-term career prospects, Lee explained. South Koreans increasingly recognize that, she said. In 2019, the government passed a new curriculum that emphasizes the importance of play in early childhood education and care

Nevertheless, many parents are still afraid to let go of what they see as proven strategies for short-term goals like getting into college. South Korea’s education system might be demanding, but it has also made the country the most highly educated in the world. Therefore, despite reforms to the public education system, parents continue to send children to private academies that stick to older strategies, like rote memorization.

“Students who are more mentally healthy are more likely to engage deeply with their learning, think creatively and adapt to the changing demands of the modern workplace,” Lee said. “But conflict arises from the deeply social and cultural emphasis on academic performance as the primary measure of success.”

Although parents understand the importance of play for child development, she added, “many are still afraid that their children will underperform compared to their peers.”

Yang, the film director, told me it takes courage for students to enroll in a school like Ggeumtle. Indeed, that was the inspiration for the “Alice in Wonderland” reference in the documentary’s title, “It’s Okay, Alice.”

“I saw the kids as Alice because they are children who bravely choose a different path, and have taken the time to travel and explore for themselves,” Yang said, adding that the wonderland—which translates to isanghan nara, or “strange country,” in Korean—is the Korean education system. “I wanted to show them that Alice is okay. It’s okay to rest, it’s okay not to do well, and it’s okay to go another way.”

Nevertheless, the persistent fear that making an unconventional choice could harm a child’s prospects may have affected enrollment at Ggeumtle.

“In the beginning, students chose this school with the aim of creating a different life for themselves,” Tae-joon Park, a 27-year-old Ggeumtle teacher, told me. “But as time went on, Ggeumtle became the only choice for our students, especially for mentally ill students or those who are not really getting it in public schools. They have no other place to go.” Ggeumtle’s principal Kim Hye-il said it’s important to serve that population by providing counseling, community and peaceful self-reflection.

“Some students apply themselves well in public schools but there are more and more who can’t adapt to this system in Korean society, and someone has to take care of these people,” he told me. “We can’t just leave them alone.”

For those students, Kim said, it’s important to communicate that different life and career goals, like being a taxi driver or guitar player or cook, are valid life choices.

Unfortunately for its students and supporters, as of this February, Ggeumtle Efterskole will no longer be around to provide that message. After the 2020 coronavirus lockdowns, the school’s enrollment declined and its persistent accounts deficit became difficult to ignore. Ultimately, Ggeumtle’s board decided to close the school.

Although Oh says he will pivot to running shorter programs for children through his other project, Island Village Life School, which currently only serves adults, the students I met, who graduated on Feb. 18, were Ggeumtle Efterskole’s final cohort.

The good news for the reform movement is that the project has a meaningful legacy: the Odyssey School, a public “transitional” school in Seoul offering a gap-year program that was directly inspired by Ggeumtle. Several other public efterskole-style boarding schools are also in the works across the country, according to Oh. These public programs, which receive support and funding from the government, will be more sustainable and accessible than Ggeumtle—a private school that cost 1,100,000 won ($822) each month to attend— ever was.

“It is time to hand over our experience to the public,” Oh said.

Although the full extent of Ggeumtle’s philosophical revolution remains to be seen, for now it’s hard to deny the impact it has had on its students.

Hours after my formal interview with Yeoreum, she found me again to tell me one last thing. At that point, we were down on the soccer field. It had started snowing halfway through the day, and rather than skipping their scheduled soccer practice, students and teachers set out early to play a game together before the ground got too slippery. Off to the side, other staff built a campfire where students could warm up and roast sweet potatoes and marshmallows.

“I forgot to tell you why I am relaxed here,” Yeoreum said, kicking a soccer ball back onto the field. “It’s because I can be myself here. No matter what other people want me to be.”

She ran off to join the game, a wide smile on her face.

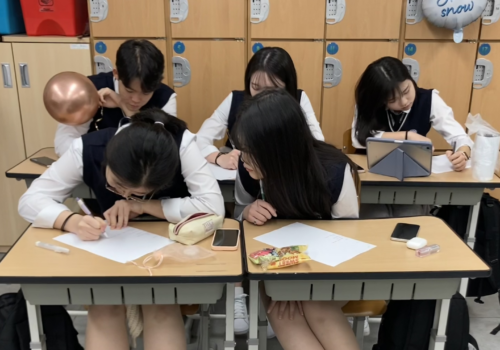

Top photo: Yeoreum in a guitar class at Ggeumtle Efterskole, on Ganghwa Island