RIYADH — Think of Jarir Bookstore as a cross between Barnes & Noble and Best Buy. The franchise is one of Saudi Arabia’s business success stories, beating back foreign rivals to become the largest book and electronics retailer in the kingdom. When I visited its flagship store in the capital on the last night of Ramadan, the ground floor was buzzing with young Saudis inspecting new iPhones and laptops, and families ogling the flat-screen TVs.

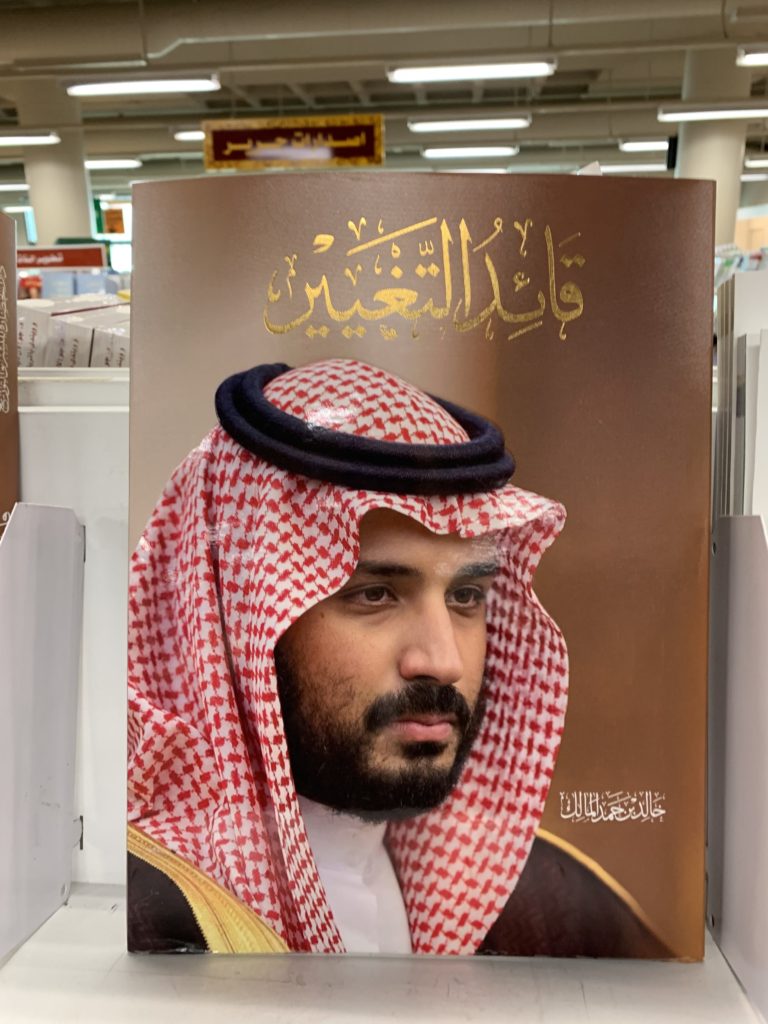

I took the stairs up to the less-crowded second floor, where the Arabic and English-language books are sold. Given pride of place on one shelf was a thick volume decorated with ornate gold calligraphy and the face of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The title read Qa’ed al-Tagheer: “Leader of Change.”

I’ve been talking with a lot of Saudis over the past two months about Vision 2030, the kingdom’s ambitious reform package. I’ve interviewed prominent Saudi businessmen and former officials, foreign investors and diplomats, and pestered my fair share of taxi drivers and young Saudis about it as well. The book went a long way toward helping me understand the perspective of a significant subset of those with whom I have talked, who remain enthusiastic supporters of the plan.

During my time in Saudi Arabia, I have come to better understand how Vision 2030 is as much a political project as a technocratic attempt to reform the kingdom’s economy. It represents an attempt to rewrite the kingdom’s basic social contract, in which citizens give the government political support in return for financial security. Saudi citizens, meanwhile, regularly draw comparisons between this moment and the preceding decade—an assessment that redounds to the benefit of Vision 2030, as the previous era was seen as bogged down by bureaucratic inertia.

Vision 2030 represents a costly proposition. The state’s leaders are funding it with the country’s massive oil revenues, betting the country can bring a new economy into existence by the time the financial buffer provided by oil erodes. It’s a big bet, and there is no guarantee of success. There is still much work that needs to be done to train the next generation of Saudis so they can find employment in the private sector—a task that involves changes to both the education system and the preconceptions of young Saudis, who will have to come to realize they can’t rely on the comfortable government jobs provided to their parents. The efforts to curb state employment are also not easy, as the government must balance the long-term necessities of reform with the short-term risks associated with creating a new generation of young, unemployed Saudis.

Leader of change

Written by the editor-in-chief of a Saudi newspaper, with an introduction by the information minister, Qa’ed al-Tagheer provides an account of Mohammed bin Salman’s major decisions since assuming a place in the kingdom’s succession in 2015. He is portrayed as having provided decisive leadership designed to modernize Saudi Arabia—a young, dynamic leader poised to bring the country into the 21st century. The book’s dedication describes him as “The prince of modernization, and tall stature, and an extraordinary statesman.”

More than anything else, Qa’ed al-Tagheer portrays a man at the center of a whirlwind of action. On one page chairing a meeting about the fate of the state oil company Aramco, on the next he is flying to Washington for a state visit with then-President Barack Obama, and finally he is conferring with world leaders at a G20 summit in Argentina. The prince is an “enemy of extremism, fanaticism and terrorism,” and the “creator of initiatives to realize the dream of the future for our country and our citizens.”

The fulsome praise for the crown prince also contains implicit criticism of how the kingdom has been governed in the recent past. And in conversations with Saudi businessmen and many well-educated, upwardly mobile Saudis, that criticism often becomes explicit. For many of those Saudis, the kingdom’s leadership has been too old—Saudi Arabia hasn’t had a monarch under 70 years of age since 1991—and too focused on consensus-building to take the sort of decisive actions necessary to meet the challenges facing the country.

I encounter frustration with Saudi Arabia’s former style of “business as usual” wherever I go. A former official at the Central Bank described how his office would unilaterally issue “circulars” to banks rather than attempt to pass new laws, as the process to win approval from the Council of Ministers could take upward of five years. Now, he said, the kingdom had passed nine new sets of laws addressing aspects of the economy in the past year.

Another former official bemoaned the succession of five-year plans that had preceded Vision 2030, stretching back to 1970. In her book about Saudi Arabia, Karen Elliott House draws a comparison between those efforts and the five-year plans drafted by the gerontocratic Soviet leadership—economic visions that existed solely on paper, bearing no relation to reality. The former official told a similar story, describing plans not taken seriously even by those who drew them up. That had come to an end with Vision 2030, he said—finally the kingdom had a strong leader with the determination to implement decisions across the sprawling bureaucracy.

Vision 2030 represents an attempt to rewrite the kingdom’s basic social contract of political support in return for financial security.

Those are the sorts of stories I often hear when I raise potential concerns about Vision 2030. I typically run through a laundry list of economic issues: Why isn’t the economy producing enough jobs to keep up with the number of young Saudis entering the job market? Why isn’t foreign investment higher? Are you sure the mega-projects envisioned by the government are calibrated to meet the country’s needs?

Yes, my interlocutors generally acknowledge, they have concerns about those issues. But they are often more liable to return to their complaints about the kingdom’s recent past than dwell on the problems of the present. The big picture is that someone is finally spearheading an ambitious strategy commensurate in scope to the challenges Saudi Arabia faces, they say. That fact is more important than concerns over the plan’s specific details–at least so far.

Vision 2030 aims to convince Saudis that the ship of state is being guided by a firm hand, of a leader determined to respond to the challenges faced by his citizens. And it aims to enlist Saudis in support of this national project. “If [Saudis] work and move in the right direction, they will create another country,” Qa’ed al-Tagheer reads.

A new economic arrangement

Whether Vision 2030 ultimately succeeds as a political project, of course, will depend on the ability to deliver on its economic promises. The perspective of regular Saudis about the prospect is somewhat different than that of society’s elite levels: Of course everyone wants a government of which they can be proud—but for citizens who depend on the state’s generous social safety net, there are concerns over what the reforms mean for the job market. The government now talks openly about its goal to push Saudis into the private sector, where jobs pay lower salaries and demand longer working hours than the cushy public sector positions enjoyed by previous generations.

The Saudis I have met aren’t opposed to a new economic arrangement, but they have yet to see the fruits of the reform effort. In Riyadh, at least, many are well-traveled; they have been to places with abundant economic opportunities, and naturally draw comparisons with the options available to them in their home country. One man I met by chance in a café described a road trip he had taken from Wisconsin, where his brother was in school, to Miami’s South Beach. Another acquaintance spoke fondly of the vista along the North Carolina coast.

On a trip to the national museum, my Uber driver described visiting Hawaii as part of a military training program. He was now a policeman in Riyadh, earning extra money for his family in his spare time. He smiled a bit cynically when I explained my project to him. “Jobs?” he said ruefully, banging on his steering wheel. “This is the only job.”

The picture painted by government statistics drives home such concerns. More than 200,000 Saudis are going to enter the job market every year for the next decade; if the government succeeds in its effort to promote greater female employment, that number could be even higher. Meanwhile, the private sector has created considerably fewer than 100,000 jobs per year since 2015. That disparity will result in either a growth in public sector jobs—a step that would run counter to the government’s long-term plans, and is ultimately financially unsustainable—or in the creation of a growing generation of unemployed Saudis.

At a fundamental level, Vision 2030 represents an attempt to rewrite the kingdom’s basic social contract of political support in return for financial security. Saudis’ perspectives on that effort depend on their position in society—the issues that loom largest for a successful businessman and a newly minted university graduate in search of his first job are bound to be different. Some consultants worry that the kingdom has frontloaded too many aspects of Vision 2030 that cause economic pain and not enough that provide tangible benefits to the population.

I descended the stairs at Jarir Bookstore and began threading my way through the crowd of young Saudis looking at the latest electronic gadgets. It was almost 11 p.m. and business showed no sign of slowing. Saudi Arabia’s massive oil revenues have enabled it to insulate its people from the worst effects of its economic restructuring so far. As to whether the state’s leaders can bring a new economy into existence by the time that buffer erodes, Qa’ed al-Tagheer says: “Seventy percent of Saudis have the passion, reliability and intelligence to achieve the impossible.”