In the bowels of Mecca’s Grand Mosque, a female jihadist grapples with a French commando. As fighting rages around them, she seizes his gun and leads them out through a warren of tunnels. In an abandoned home, their hatred soon turns to lust. The jihadist, Sarab, and the French soldier, Raphael, begin a whirlwind romance that takes them to Yemen, Somalia and France before she is assassinated by her former compatriots on Paris’s Boulevard Haussmann. Her lover arrives just before she dies to ease her passage into the world beyond.

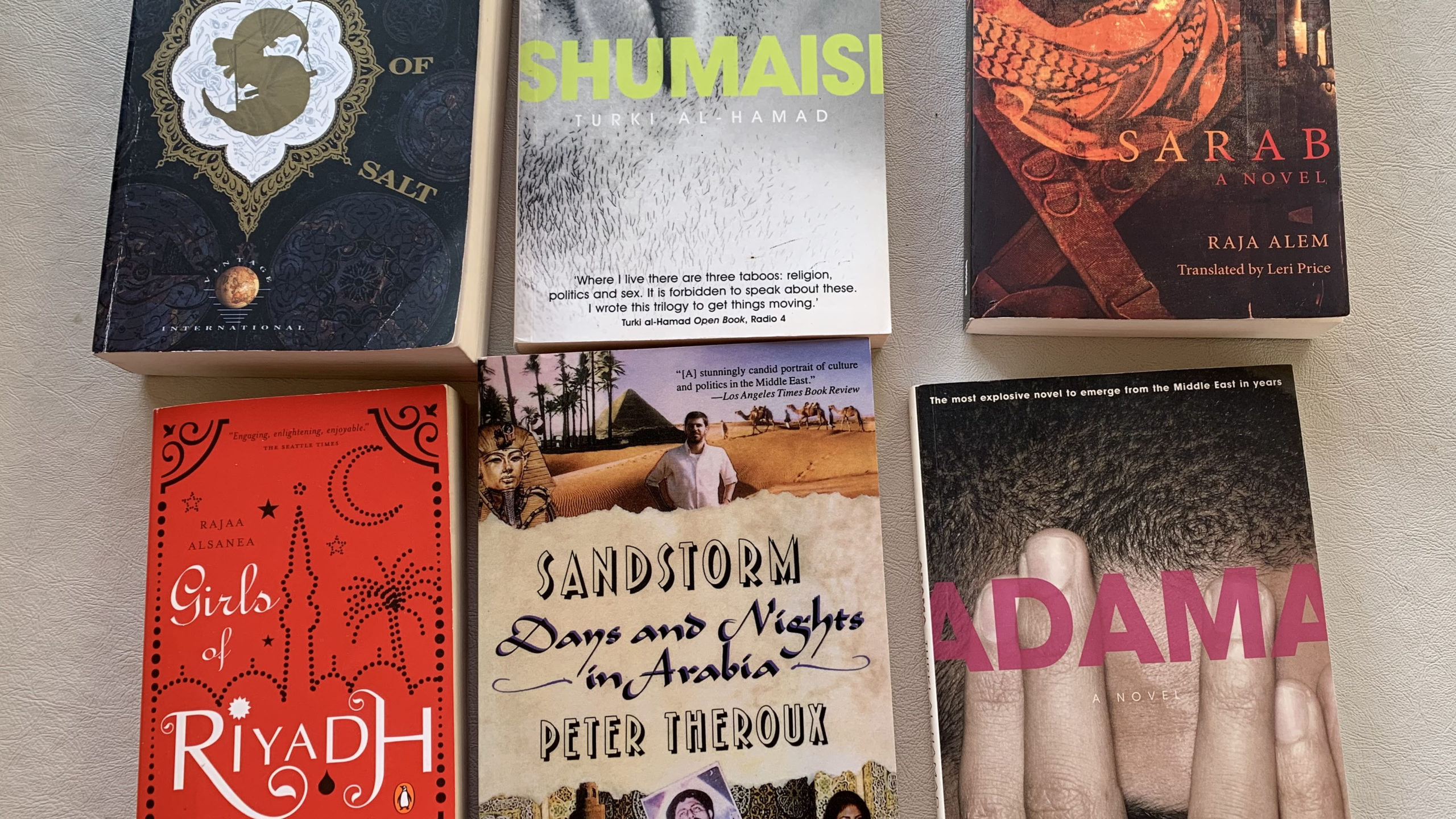

So goes the plot of Raja Alem’s novel Sarab (2018), which uses one of the most infamous events in modern Saudi history to explore the love-hate relationship between the West and the Arab world. The novel’s ending represents a triumph despite Sarab’s death as the characters finally shed their national identities and embrace a broader human bond. “There was no longer any concept of being a stranger, a foreigner, or an exile here; they were all a single essence flowing with the name of God.”

It is a matter of historical fact that jihadists seized the Grand Mosque in 1979 to proclaim the coming of the Mahdi before their defeat in a Saudi military assault, aided by French special forces who advised from afar. From there, however, Alem’s story grows increasingly fantastical. Where is the novel grounded in reality, and where is it spinning a story? Are Sarab and Raphael stand-ins for all their countrymen or characters specific to the world of the novel?

As in much Saudi fiction, ideas and emotions that typically remain unexpressed in everyday life bubble to the surface in Alem’s book. By blurring the lines between real and imagined, fiction writers are able to maintain a certain ambiguity about when their commentary on real-world issues ends and the fictional drama of their characters begins. Some novels and short stories even go so far as suggesting radical critiques of the kingdom’s social and political order that would be unthinkable if delivered explicitly. They provide vivid examples of how red lines of public discourse apply even to imagined worlds.

In my experience, Saudi readers are extremely sensitive analysts of works of fiction. It is common practice to embed political messages in art: To take one example, a prominent minister once published a poem that imagined the criticisms the medieval poet al-Mutanabbi might have levied against his powerful patron. The poem was widely interpreted as a broadside against King Fahd and the minister was promptly dismissed. Fiction that delves into politics is typically read through the same discerning lens, not as works of mere entertainment or escapism.

The kingdom’s ideological debates have also often played out on the literary field. One Saudi friend described to me how the cultural supplements of newspapers and the country’s literary clubs serve as battlegrounds between Islamists and “modernists” who hold starkly different worldviews. The poetry and prose published and analyzed by those outlets stand in for larger debates over the groups’ competing visions.

Poetry has been recited on the Arabian Peninsula since before the advent of Islam in the seventh century and maintains pride of place as a mode of literary expression. Even today, major Saudi festivals often showcase poetry readings. But there is an audience for prose as well: Short story writers often publish their works in newspapers before compiling them in books. But many Saudi novels are published outside the country—most notably in Beirut by the publishing house Dar al-Saqi. The distance allows the authors to tackle provocative political and social issues while also dodging the censors.

Authors have used literature to assail the strict gender segregation and patriarchal norms enforced by society and the state since as far back as the 1960s. Ironically, because fiction writing does not risk gender mixing or involve organizing activists around an explicit goal, there are no legal restrictions against it. While Sarab sometimes reads like a political thriller, other female authors choose to focus on the lives of normal people in Saudi towns and villages.

They include Sharifa Shamlan, a Saudi writer born in 1946 whose short stories are drawn from the women she encounters as a social worker in the eastern city of Dammam. They often portray women driven mad by a range of oppressors, from husbands to family to society.

Secret and Death (1989) tells the story of Zahra, a woman living in an unnamed village. Boys throw rocks at her and jeer about “the crazy one” whenever she washes clothes by the river. The rumor of her insanity has been spread by her stepmother, who fears she would one day marry her brother. Zahra does appear to be legitimately disturbed: At one point, she dances in the street until collapsing in the dirt and later applies makeup so that “her face looked like a painting scribbled by a careless child.”

Zahra eventually does strike up a relationship with the brother, who impregnates her. As her belly swells, so does her foot from stepping on a thorn while hauling laundry back to the village. The belly naturally attracts all the attention, and soon the village is in an uproar over who got her pregnant out of wedlock. Zahra remains silent, however, determined to protect her lover. When the authorities question her, “she howled like a hungry, sick wolf.”

Zahra is eventually hauled off to a state institution and disappears from the narrative. She reappears only two months later, when a letter announces that she and her unborn child have died from the infection in her foot.

Like so many of Shamlan’s protagonists, Zahra’s insanity provides her with a clarity absent in the other characters. It is also a useful device to win over readers: A sane protagonist who railed angrily against the injustices of Saudi society would be making a clearly political statement; an insane character, however, represents a victim deserving of sympathy. Zahra’s condition is portrayed as a result of the burdens placed on her—she is a casualty of society’s repressive attitudes despite her good soul. As she is being led off, her lover watches mournfully. “She is not crazy, she is the most sane of all the sane,” he thinks. “She had protected him, the sane, while he let her down.”

Society’s focus on Zahra’s pregnancy and its apathy toward her swollen foot also amounts to a biting criticism of social norms. In both the story and real life, society is obsessed with women’s virtue—the action in the plot derives entirely from the outrage over the fact that Zahra evidently had sex out of wedlock. At the same time, however, the story suggests that society ignores women’s legitimate concerns about health and safety. It cares about them only as symbols of virtue, not actual human beings.

Saudi literature is notable for what it omits. Assailing societal norms in fiction appears to be accepted but offering alternatives seems to be a bridge too far.

Shamlan’s stories are also notable for what they omit. While she invariably portrays her female protagonists as tortured souls, she stops short of offering a model of a more just society. Assailing societal norms in fiction appears to be accepted, but offering alternatives seems to be a bridge too far.

When it comes to style, there is a simplicity to Shamlan’s plots and writing that detracts from her work. Her stories possess a stream-of-consciousness quality, accentuated by her regular use of ellipses to separate thoughts and actions. Other Saudi writers, meanwhile, go too far in the opposite direction, creating overly verbose characters prone to long monologues about literature and philosophy. While some works are of course stylistically excellent, in my experience the body of Saudi fiction tends to suffer from a culture of criticism that focuses more on the ideological message of a work than its technique—or the absence of a shared literary community altogether.

Sex is never mentioned in “Secret and Death.” The reader is told only that Zahra has arranged a regular meeting with her lover, and next that she is pregnant. She is described as someone searching for emotional support, not sexual pleasure. However, today’s Saudi female novelists write far more explicitly about the sexual desires of their characters. Samar al-Muqrin’s Women of Vice portrays a woman who escapes a loveless marriage through an affair in London while Saba al-Hirz’s The Others tells the story of a lesbian Shiite who has a range of graphic sexual encounters with women she meets on Internet chatboards.

The most famous of these new novels, by far, is Rajaa AlSanea’s Girls of Riyadh (2005). The novel is self-consciously styled as a Saudi variant of Sex and the City, following the lives of four upper-class girls as they navigate love and marriage. These women roam around Riyadh in cars with tinted windows, strike up secret relationships with men they meet at the mall and school, and jet off to Britain and the United States. Still, they continuously find themselves thwarted and brokenhearted by the restrictions society places on them. “Love was treated like an inappropriate joke,” one character fumes. “A soccer ball to play with for a while until those in power kicked it away.”

While AlSanea’s characters enjoy opportunities that would be utterly alien to Shamlan’s protagonists, in both cases those wielding power over them are fathers, husbands or other family members. Members of society are the chief villains, while the state’s enforcers of patriarchal order are largely absent.

The characters in Girls of Riyadh are determinedly apolitical, showing virtually no interest in larger issues of equality and injustice throughout the kingdom. They are struggling for their own personal freedoms, not broader social or political liberties. “All of her classmates and everyone of their age were on the margins when it came to political life,” another character muses. “They had no role, no importance.”

Girls of Riyadh portrays the indifference as a failing of the modern Saudi generation, but offers no solutions. At one point, however, the novel hints at a more biting criticism of the Saudi state: A spoiled, manipulative princess flits through the narrative, abusing the friendship of one of the protagonists before cutting off all contact when she is no longer useful. That is the sole time the royal family appears in the novel. Does AlSanea intend for the princess to stand in for the Al Saud family? The ambiguity is where the power and protection offered by fiction lies.

If books about Saudi society often touch obliquely on politics, some novelists who purport to explore the kingdom’s political reality have perfected the art of skirting truly sensitive issues. Turki al-Hamad’s “Specters in Deserted Alleys” trilogy tells a coming of age story set in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time of huge ideological tumult in Saudi Arabia. In the first novel, the protagonist, Hisham al-Abir, joins an underground Baathist cell plotting a coup to overthrow the monarchy, while in the second novel, his best friend falls under the sway of Islamists.

The characters’ political awakening takes place alongside their sexual awakening, particularly after Hisham travels from Dammam to Riyadh searching for the illicit, half-hidden pleasures of sex and alcohol in the capital, where “everything is forbidden, and everything permitted.”

But while Hamad’s characters earnestly quote Karl Marx and Jean-Paul Sartre, they have precious little to say about the political reality in Saudi Arabia. Their intellectual energy is consumed by endless internecine battles between Baathists, Communists and Nasserists, and as a result they rarely levy any truly damning criticisms against the state. Yes, the monarchy is portrayed as brutal against its foes—particularly in the third novel, al-Karadib (1998), in which Hisham is tortured at a prison near Jeddah. But so are Hisham’s erstwhile Baathist comrades, who are trying to establish a mirror image of the oppressive institutions they want to overthrow.

The result is a series about politics in Saudi Arabia that doesn’t have much to say about the dominant force in politics. What are the roots of the Saudi state’s power and the sources of dissatisfaction in the kingdom? If Hamad’s revolutionaries believe so fervently that the government must be overthrown, in what ways do they believe it is damaging the country? The book is silent on all those questions.

Although Hisham hails from the kingdom’s oil-producing east, Hamad barely mentions the role of oil in shaping lives and the fortunes of the state. But for Bandar bin Surur, a Saudi poet writing in the years when oil was first transforming Saudi Arabia, it constitutes a central theme of his work. “Curse the Christian who found the oil,” he writes. “Would that the gushing oil blind his eyes.”

A member of the Otaiba tribe, Bandar bin Surur condemns oil for making Saudis fat and complacent. The discovery of the massive wealth below their feet sounds the death knell for the dominance of the heroic Bedouin tribesman who had survived in the desert in previous generations through courageous acts and feats of endurance. At the same time, he vividly describes how the central state used this new wealth to tame and domesticate once-powerful tribal chiefs. “The chiefs of Najd’s tribes who uprooted the mighty armies, have become docile and content to feed, like chicken, on grain thrown on dirt,” he writes.

The most famous work of Saudi fiction that deals with the discovery of oil in the kingdom is Abdelrahman al-Munif’s “Cities of Salt” quintet. The son of a Saudi caravan trader and an Iraqi mother, he was born in Amman, Jordan, just a few months after an American company won the first concession to drill for oil in Saudi Arabia. His life was intertwined with the oil-fueled transformation of the Arab world: He received a PhD in petroleum economics from Belgrade University in 1961 and went on to work at the Syrian Oil Ministry until the early 1970s.

Cities of Salt (1984), the first book of the quintet,tells the story of Wadi al-Uyoun, an Edenic village in the fictional Sultanate of Mooran, a thinly veiled stand-in for Saudi Arabia. Crucially, there is no sanctuary of ambiguity here: For anyone who knows Saudi history, Munif’s work includes unmistakable references to specific events and figures, including kings and prominent ministers. It is impossible to read the novels as anything other than a commentary on modern Saudi Arabia.

Munif lovingly paints a portrait of Wadi al-Uyoun’s residents on the eve of the discovery of oil. The town’s relatively egalitarian social order is overturned by the coming of Aramco, as the influx of wealth makes authority more distant and brutal. Suspicion and hostility gradually replace traditional methods of consensus-building as different groups vie for the favor of the all-powerful American oilmen.

Wadi al-Uyoun is eventually bulldozed and its residents suffer both physical and intellectual dislocation. “How is it possible for people and places to change so entirely that they lose any connection with what they used to be?” Munif writes. “Can a man adapt to new things and new places without losing a part of himself?”

The authorities are portrayed as complicit in the destruction. Enthralled by the wealth and technology brought by the Americans, they neglect citizens’ needs. In one scene, the local emir gathers his friends at twilight to hear a radio for the first time. As he theatrically turns on the device, each station he tunes in recites a famous warning from Islamic and Arab history about the corrupting power of wealth. Completely focused on impressing his guests with his mastery of the radio, however, the emir is deaf to the programs’ message. “As you have seen, my friends,” he piously says at the end of the performance, quoting the Quran, “God teacheth man that which he knew not.”

The second and third books of the series continue Cities of Salt’s efforts to demolish the state’s foundational myths. The Trench pillories the backstabbing and corruption at the court of King Saud in the early 1960s, particularly among the foreign courtiers who flock to the kingdom as its wealth grows. Variations on Night and Day retells the story of the kingdom’s unification, portraying the country’s founder Abdelaziz as a Machiavellian schemer who rises to power through connivance with the British.

Munif’s anger at the Saudi government stemmed from his belief that it was squandering the vast oil wealth at its disposal. Peter Theroux, the translator of Cities of Salt who began his career as a journalist in Riyadh and went on to spend two decades as a CIA analyst, recounts a 1988 meeting with the author in his memoir Sandstorms. Oil, Munif fumed, was “the first and last and only chance for the Arabs to do something for themselves.”

Ironically, although Munif castigates Western infiltration for perverting politics and society, even the author himself could not escape the intellectual pull of the United States. He had come across the idea for Cities of Salt, he told Theroux, while visiting the abandoned gold mines of northern California. “Someday the oil wells of Saudi Arabia will look like that,” he said. “Does anyone in the Saudi government realize that?”

The government not only banned Cities of Salt, it also stripped Munif of his citizenship. But while the series remains outlawed today, other Munif works are available. East of the Mediterranean, a short, bleak novel that has never been translated into English, tells the story of Rajab, who is imprisoned by a tyrannical government and suffers all types of graphic torture for years. He agrees to inform on members of a clandestine organization after the government imprisons his brother-in-law, and is eventually released from prison defeated and blinded. At the end of the novel, his wife finds his young son building Molotov cocktails in a futile attempt to free his father from prison.

The novel provides a vivid illustration of how tyrannical governments squelch intellectual and political life. Its ending also contains a warning about how future generations will take vengeance on the region’s rulers for their atrocities. But there is nothing specifically “Saudi” about it—as the title suggests, it could take place anywhere in the Arab world. In this case, at least, Munif successfully maintains the ambiguity between real and imagined.

I first came across a copy of East of the Mediterranean while perusing the library at the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, a futuristic museum built and operated by Aramco in eastern Saudi Arabia. The company envisions the site as a “modern center of culture and learning” that would represent a “model for social progress” in the kingdom. As I leafed through the book, I had my doubts whether Munif would appreciate the irony of the situation.

Top photo: Rub al-Khali desert in Saudi Arabia (Javierblas, Wikimedia Commons)