The ongoing migration of Russian exiles before and after the Kremlin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine is much more “fluid, dynamic and ambiguous” than the emigres’ majority demographic—highly skilled young workers from major Russian cities—might initially suggest, returning ICWA fellow Aron Ouzilevski said in his final report at the US Institute of Peace on November 8.

Based in Tbilisi, Georgia, Aron spent two years writing about Russians fleeing authoritarianism, militarism, mobilization and a deteriorating economy at home. He traveled widely to emigre hubs in Europe and beyond, observing on the ground how political opposition leaders, creative and tech professionals, activists, journalists and civil society are adapting to new lives and careers, how they’re affecting their host countries and what they reflect about President Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Many immigrants are in limbo and struggle to define themselves, Aron observed. “The term ‘exile’ or izgnaniye feels too permanent or implies they were forced out for political reasons,” he said. At the same time, “emigre” implies integration into a new country, which those living and working in “isolated Russian bubbles” in waypoint destinations like Georgia don’t experience. Many emigres maintain ties to Russia, returning to visit family members or working remotely in the Russian economy. Many who left for political reasons are often unwilling to live in refugee camps to obtain humanitarian visas in Europe.

Their futures are difficult to predict since they depend on broader global events in their host countries and the outcome of war in Ukraine. “Still, based on my own sample size and excluding activists and journalists facing criminal charges back home, around 70 percent of immigrants remain resolute in their decision to stay abroad,” Aron reported. “Their stories reveal how an authoritarian regime can deceive and pacify a generation of critically minded individuals by masking its hostility.”

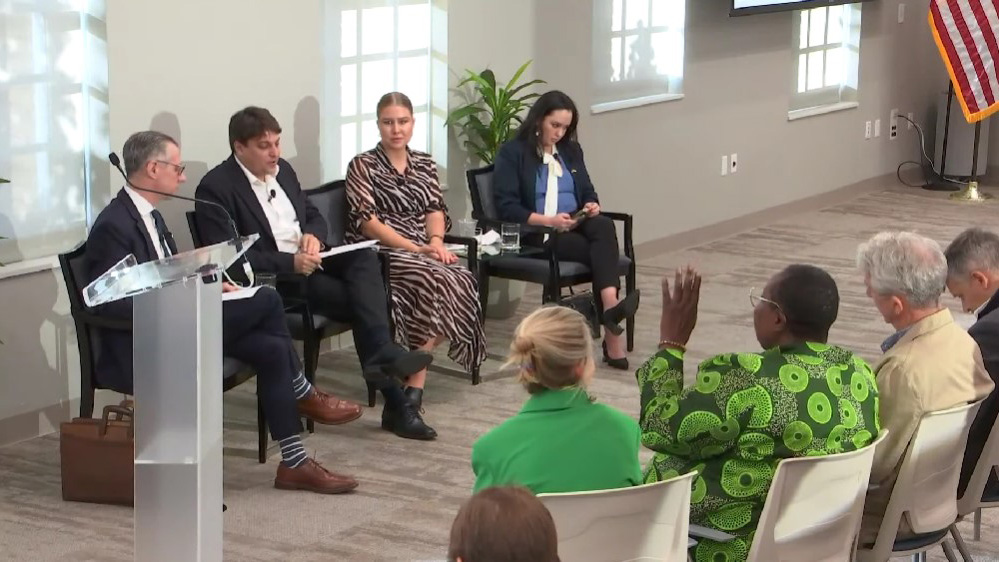

Following his talk, Aron joined a panel discussion with the leading exiles Lyubov Sobol and Anna Veduta discussing wider implications of his research and what the future may hold for Russian emigres and their home country, moderated by ICWA’s Gregory Feifer.

Veduta—director of strategic engagement at the Washington DC-based Free Russia Foundation, and former spokesperson for the late opposition leader Alexei Navalny—emphasized that Russian support for Putin’s war is not as huge as Kremlin propaganda or the media lead us to believe. “We don’t see any lines at conscription centers,” she said. “It’s not a patriotic war for Russians.” She conservatively estimates that 20 percent of Russians support the war, while a silent majority tries to go on with life as if it isn’t happening.

Sobol, a leading opposition politician who was a close ally of Navalny, urged US and European governments to promote democratic values by granting tourist visas to Russian citizens. “Before the Ukraine war in 2022, Russians could go abroad and see with their own eyes that Europe and France and Germany are not the enemy, that people are very polite and welcoming to Russians,” she said. “But now visas are difficult to obtain, feeding Kremlin propaganda that the West doesn’t like Russians because they don’t even let them enter their countries.”

Read Aron’s dispatches here.

Speaker

Aron Ouzilevski has worked as a freelance journalist, editor and cybersecurity analyst. His research and writing has focused on Soviet and contemporary Russian politics and culture, and his work has appeared in The Guardian, The Economist and The Moscow Times. He holds a joint masters degree in global journalism and Russian/Slavic Studies from New York University.

Aron Ouzilevski has worked as a freelance journalist, editor and cybersecurity analyst. His research and writing has focused on Soviet and contemporary Russian politics and culture, and his work has appeared in The Guardian, The Economist and The Moscow Times. He holds a joint masters degree in global journalism and Russian/Slavic Studies from New York University.

Panel

Lyubov Sobol is a Russian opposition politician.  She conducted journalistic investigations into corruption in Russia while serving as a lawyer for Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation. Currently, she leads anti-propaganda projects on YouTube, attracting hundreds of thousands of viewers. In 2023, Sobol was a senior fellow with the Center for European Policy Analysis.

She conducted journalistic investigations into corruption in Russia while serving as a lawyer for Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation. Currently, she leads anti-propaganda projects on YouTube, attracting hundreds of thousands of viewers. In 2023, Sobol was a senior fellow with the Center for European Policy Analysis.

Anna Veduta is director of strategic engagement at the Free Russia Foundation. She is an expert in strategic communication and international affairs who began her career as the first press secretary to the opposition leader Alexei Navalny. She served as a global outreach director for the leading Russian media platform Meduza, spearheading its international presence. Returning to the Navalny-founded Anti-Corruption Foundation as vice president, she later led advocacy efforts in Washington, D.C.

Anna Veduta is director of strategic engagement at the Free Russia Foundation. She is an expert in strategic communication and international affairs who began her career as the first press secretary to the opposition leader Alexei Navalny. She served as a global outreach director for the leading Russian media platform Meduza, spearheading its international presence. Returning to the Navalny-founded Anti-Corruption Foundation as vice president, she later led advocacy efforts in Washington, D.C.

Moderator

Gregory Feifer is executive director of the Institute of Current World Affairs and a fellow in Russia in 2000 – 2002. A former Moscow correspondent for National Public Radio, his books include Russians: The People Behind the Power. He has written for numerous publications, including The New York Times, Foreign Affairs and The Times Literary Supplement, and is working on a biography of the Russian politician Boris Nemtsov.

Gregory Feifer is executive director of the Institute of Current World Affairs and a fellow in Russia in 2000 – 2002. A former Moscow correspondent for National Public Radio, his books include Russians: The People Behind the Power. He has written for numerous publications, including The New York Times, Foreign Affairs and The Times Literary Supplement, and is working on a biography of the Russian politician Boris Nemtsov.

‘Russians in exile’ text

On a spring evening in Tbilisi, Georgia, one year into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a young designer from St. Petersburg in her late 20s, sat slumped on a curb outside a Russian owned pop-up shop where a birthday was being celebrated.

Clutching a bottle of wine, she screamed at the world in her native Russian.

“This system,” she began, referring to Vladimir Putin’s Russia. “And this motherfing Putin! They gaslit us, they gaslit us on all fronts. We were told we defeated fascism, and now, motherfer, we’re resurrecting fascism!”

She rambled into a story about her grandmother, who survived the Second World War only to die of COVID-19 complications after catching it from paramedics—a victim, she said, of the same “system” and its neglect. Her rant, punctuated with expletives, drew hushed comments from her friends, who urged her to quiet down. In Tbilisi—a city with a strong anti-Russian sentiment, lingering from Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia and reignited by Russia’s war in Ukraine—loud, angry Russian could easily invite reprimands. In some venues, Russian passport holders weren’t even allowed.

But she didn’t care. “I want everyone in this city to hear me!” she shouted.

Her outburst, to me, captured the essence Russia’s current wave of emigration. She fit the profile of the majority demographic leaving the country: urban, middle class, educated, with access to social capital, wearing trendy clothing, between 25 and 40 years old, from a major Russian city. Her tone—which both felt performative and painfully real—was laced with confusion and disorientation, as if the political reality of the regime she grew up under had hither like a train on February 24, 2022, the day the full-scale invasion began.

For people like her, life in Putin’s Russia had been comfortable. The chaos and poverty of the 1990s—brought upon by Russia’s violent embrace of capitalism—was long gone. Despite geopolitical tensions, there were still connections with Western institutions in the arts, tech, science, and academia. Innovation was thriving, and the budgets of oligarchs—ballooned with the help of corruption and natural resources—had transformed Moscow and St. Petersburg into incredibly modern cities, sometimes even more comfortable, according to the complaints of recent Russian emigres in Germany, than European capitals like Berlin.

Yet, in the years leading up to the invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin had waged a war with Georgia, illegally annexed Crimea, started a hybrid war in Eastern Ukraine, poisoned, murdered, and imprisoned political opponents, staged show trials, and attacked civil society organizations. Still, for many, financial stability and career growth took precedence over politics.

For most Russians, politics was either passé or taboo—too mundane to care about or too intimidating to confront. How do you stand up to a state with such a sophisticated security apparatus? Instead, why not launch a podcast about how Russians in the first generation of newfound wealth can spend it effectively?

Even many of Russia’s most politicized people, from independent journalists to open political dissidents, tacitly signed an unofficial social contract with the Kremlin. With each year, they would continue to adapt to new restrictions the government would introduce, and hope that eventually, the modernization of Russian cities would in turn pull its government into the 21st century.

In a recent interview, the renowned exiled film critic Anton Dolin reflected on why Russia’s liberal class tolerated Vladimir Putin’s regime for so long: “We thought we were just living under a party of ‘crooks and thieves,’” he said. His comment, referencing Alexei Navalny’s expression for the United Russia ruling party and its corruption, suggested that Russia’s liberal class had overlooked the deeper forces of imperialism, nationalism, and militarism lying beneath Putin’s rule.

Still, for many, the war—and the intense repression that followed—became a red line. Yet it was also a shock, catching people off guard, with many fleeing the country before fully processing what had just happened to them.

This ambiguity is central to understanding this wave of Russian emigration. Many emigrants struggle to define themselves. For some, the term “exile” (izgnany) feels too permanent, or implies that they were forced out for political reasons. But when Putin announced the partial mobilization in September 2022 to bolster the front lines, many Russian men fled not because of any specific political targeting but out of fear of conscription.

Many of the emigres I spoke with are also in limbo, with one foot still in Russia, one foot out; many continue to return temporarily for work projects, or family visits. Many work remotely on the Russian market.

Even the number of emigres remains contested. Some researchers estimate that 1 million Russians have left since the invasion, while others indicate that this number is decreasing, as many individuals are returning.

The term “émigré” also feels off to many—it implies integration into a new country, a process many in “waypoint countries” like Georgia don’t envision.

This ambiguity also reflects the nature of Putin’s regime itself—its policies and ideology.

Consider the pro-war Latin “Z” symbol. Originally a military marking, it gained traction online among pro-war groups, and the government adopted it as a unifying emblem. Its origins have no ideological basis. Meanwhile, the Kremlin still refuses to call the invasion a war, opting for the euphemism “special military operation” to downplay the conflict’s scope. Most Russians feel the war is distant; the fighting rarely reaches them directly, and many soldiers are contractors seeking a payout, not patriotic glory.

One exile I spoke with, an avant-garde theater director who fled Russia after police raided his home due to his anti-war performances staged in Moscow’s metros, described the regime’s ideology as “boring fascism,” highlighting its vacuous nature.

This pervasive ambiguity shapes the psychology of many émigrés. Just as the Kremlin—a hybrid, quasi-fascist regime—wages a war that it does not call a war, this migration is itself a hybrid phenomenon. While most I spoke with are resolved in their decision to leave, often citing their inability to accept the “new, militaristic reality,” some have expressed doubt about their departure.

Take a Siberian lawyer who defended victims of human rights abuses, including journalists and Navalny campaign members. Initially fearing for his safety, he left Russia, but the choice strained his family; his wife and children remain behind, and a new suitor has entered the picture. Towards the end of our conversation, he pondered if he should have stayed, kept his head down, and shifted to a different practice, noting how much more money professionals are making in Russia now.

Another respondent, a 31-year-old composer, recently told me he felt “gaslit” by Russia’s opposition, who convinced him that if he didn’t leave by March 2022, he’d lose his chance forever, as rumors swirled that Russia would close its borders imminently. His experience in Tbilisi was difficult—his Georgian relatives—he is part Georgian—stole $10,000 in cash from him while offering him shelter, and he faced hostility due to his Russian background, which compounded his trauma. Yet he directed his anger at Russian liberals, blaming them for his decision to leave—a decision, he now seems to regret. This was a man, mind you, who cried the day Alexei Navalny died.

Now, I want to discuss the different waves of migration from Russia, which actually began in 2021, the year leading up to the invasion. This was the year when the Kremlin began ramping up its repressive measures, labeling Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation as extremist and drastically expanding its list of “undesirable organizations.” This crackdown prompted the evacuation of hundreds of activists, initially to Georgia, and later to the Baltic countries and Poland under humanitarian visas. Since my co-panelists were involved in some of these processes, I’m happy to explore this further in our discussion.

The second, major wave began in March 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In response to the new draconian wartime censorship laws, rumors of imminent martial law, and the threat of potential border closures, approximately half a million Russians—journalists, tech workers, creatives, academics, entrepreneurs, and activists from its major cities—left the country in the months that followed.

Operating on little more than hearsay, many fled in a panic during the first weeks of the war, scrambling to secure flights to former Soviet countries with visa-free travel, as ticket prices soared. Some of my own friends from St. Petersburg ended up in Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second largest city, simply because it was the cheapest available flight. One friend even got a tattoo of the city’s name later, a token of gratitude for the warm welcome he received from the local community.

Then, in September 2022, the announcement of partial mobilization sparked yet another wave of emigration. Around 400,000 more Russians, primarily men, fled, fearing conscription into the military and the escalating war. Once again, desperation took over: thousands of Russians fled by car to any neighboring country with visa-free access, including Mongolia and Kazakhstan.

Since those major waves of emigration, Russians—who may have lacked the resources to leave initially—continue to depart.

This summer in Serbia, I met two LGBTQ+ exiles who had only left Russia a few months prior, after the government labeled the LGBTQ+ movement as extremist. One, an activist, stayed behind after the start of the invasion to help the most vulnerable until her work became too dangerous, while the other, a 31-year-old trans artist and bartender, left when his parents finally saved enough money for his departure.

This August, I had a particularly poignant conversation with a couple who were visiting their son in Tbilisi from Russia. At first, I hesitated to mention my research, assuming they might prefer to avoid politics altogether. But when they asked about the best places to emigrate, I was surprised to realize that they were asking for themselves. The father, a music teacher, described how patriotic songs had been added to the curriculum at his music school, and a portrait of Putin had appeared in the elevator. The atmosphere in Russia, they said, had become unbearable.

This Russian emigre wave is primarily comprised of highly skilled workers from Russia’s major cities. Many retained remote jobs for the Russian market, while others have created new jobs to service their compatriots abroad. Their adaptability and resourcefulness have allowed them to quickly rebuild their lives in exile. The speed with which they established new mutual support networks and infrastructures—in just weeks following the invasion—is extraordinary.

Telegram chats swiftly became bustling hubs for everything from housing and job opportunities to cultural events and even niche services like dog-sitting. Simultaneously, new volunteer-driven civil society organizations emerged, offering aid to Ukrainians fleeing war, setting up shelters and offering psychological help for fellow Russians fleeing repression, and even facilitating the evacuation of Russian conscripts seeking to dodge the draft.

Beloved Russian musicians who stood up against the war are now touring cities like Tbilisi, Yerevan, Belgrade, Almaty, Vilnius and Berlin instead of performing across Russia.

In countries where barriers to entry are lower, many Russians have opened new businesses or transplanted familiar ones—coffee shops, bars, sleek bookstores, galleries and yoga studios—that reflect the cultural tastes of their previous lives. Places like Tbilisi, Yerevan, and Belgrade have become hotbeds for these new ventures, infused with the energy of emigres from Russia’s more developed economy.

In many ways, this migration represents a profound shift—one of the few times in history that people have fled the imperial center to settle in former colonies. In the present day, these shifts resemble a form of gentrification.

What also sets this wave of migration apart is its distinctly 21st-century character. The rise of digital nomadism and remote work—accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic—has provided émigrés with a unique flexibility, allowing them to continue their careers while living abroad. This adaptability has made this migration far more fluid and dynamic than the migrations of previous generations.

I feel it’s important to also note that this wave of emigration is not confined to those with social capital. Among my respondents were state university professors from Russia’s Volgograd region, who, despite their low salaries, chose to leave because they could no longer tolerate the propaganda infiltrating their schools or the passivity of their colleagues.

There was also a middle-aged archaeological assistant-turned-house cleaner, who fled after calling his pro-war colleagues at Moscow’s Archeology Institute “deranged” and now cleans homes for more affluent Russians in Tbilisi. Additionally, ethnic minorities from Russia’s republics joined the exodus, including a Buryat Buddhist monk, who felt his religion was being manipulated by federal secret services to shape public opinion in Russia’s Far East.

Now, in each place that Russians arrive there is always a particular context.

In Georgia, anti-Russian sentiments run deep, largely fueled by the 2008 war and the country’s strong identification with Ukraine, as well as its aspirations for European integration. In Tbilisi, Russian and Georgian communities live in parallel realities; Georgians boycott Russian-owned establishments, while Georgian civil society seldom reached out to Russian activists.

By contrast, Armenians have taken a different approach. Facing their own aggressors in Azerbaijan and Turkey, Armenians tend to view Russians more neutrally. During last year’s crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh, which led to Armenia’s loss of territories, Russian exiles were among the first to respond, providing housing and creating digital infrastructures that collected food, clothing and other supplies for Armenian refugees. As Armenian author Narine Agbaryan put it, “It was a show of humanity and unity that felt very natural, and we Armenians were warmed by these gestures, which reminded us that were not alone.”

Meanwhile, in Serbia, a country shaped by its historical losses in the Yugoslav wars and its resentment toward NATO and the West, a strong pro-Russian sentiment endures. In new, Russian-owned bars, you’ll often find Serbian men raising a glass to their “Slavic brothers,” much to the embarrassment of the proprietors.

In the face of today’s global uncertainty, it’s difficult to predict the future for this group. Everything is in flux. Those who left Russia in March 2022, hoping to return within a year after a Ukrainian victory that might trigger regime change at home, now face a different reality: the war has entered its third year, and Ukraine’s prospects of total victory seem to grow dimmer, particularly with recent shifts in US politics. There’s a scenario in which a Trump administration could end the war, potentially prompting a significant return.

Still, a large number—based on my own sample size, around 70 percent [and this is excluding activists and journalists facing criminal charges back home]—remain resolute in their decision to stay abroad. Some jokingly describe their emigration status with the acronym PPZH, Poka Putin Zhiv (“While Putin Remains Alive”), a play on the bureaucratic acronym VNZH (Vid na zhitelstvo), which translates to residency permit.

Ultimately, their fates will depend on broader global events. Take the specific example of Georgia, where tens of thousands of Russians still reside. The recent Georgian election remains contested, with the ruling party—accused of pro-Russian sympathies and even suspected of Kremlin influence—claiming victory.

Most Russians in Georgia deeply oppose this party, which has cracked down on civil society and the LGBTQ+ movement—trends the Russians themselves fled from. However, Georgia’s liberal opposition, leaning heavily on anti-Russian sentiment, has pledged to impose visa restrictions on Russians, which would potentially compromise the status of anti-war Russians in Georgia. Once again, these exiles are caught between two fires, trapped in a state of flux and ambiguity.

In a place like Georgia, my project also raised ethical questions. Many Georgians and Ukrainians might wonder why I focus on people from the aggressor’s country—those they see as privileged, still sipping lattes in exile while Ukrainians flee destruction. I felt this tension acutely in my first months of the fellowship, living with a Ukrainian roommate. After yet another missile barrage on Ukraine, I watched her cry, fearing for her grandmother’s safety. In those moments, it was difficult to sit down and transcribe interviews with Russians.

But when asked why these people deserve a voice, I answer that their stories reveal how an authoritarian regime can deceive and pacify a generation of critically minded individuals by masking its hostility. Through their backstories—which I’ve explored carefully in my writing—we can better understand the mechanisms that enabled Putin’s regime to endure.