Warsaw — The Liquidation of the Russian Federation Act! Political Governance Act! Liberation of Russia Act! The Creation of the Russian Republic Act! The Decolonization of Russia Act! The Transition Period Act! The Future of Russia Act! The Rationalization of the Russian Federation Act! The proposed names for a legislative document whose author claimed would equal the significance of the Bolsheviks’ revolutionary Decree on Land—abolishing private property in the name of the peasantry—sounded across the room like the cracks of a whip.

“Slow down, everyone; keep in mind that we’re going to have to vote for one of these names by the end of the day, which is in an hour,” a delegate who had offered to take minutes said.

After about 10 more minutes of deliberating, the delegates proceed to vote. The majority of the 76 participants––composed of former Russian officials who oppose Russian President Putin’s war in Ukraine, some present through Zoom, some in person––eventually voted for the “Transition Period Act.”

Having given themselves just four days to determine the political structure of what in their vision would be an entirely new state, the delegates appeared to be taking some decisions of potentially monumental consequence very hastily, especially with fatigue setting in. Besides, with hands fidgeting and stomachs audibly growling, the most immediate goal was dinner.

It was the first day of the Second Congress of People’s Deputies, a self-proclaimed Russian parliament in exile that met for four days leading up to the one-year anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine to debate the contours of the state that could emerge after the collapse of Putin’s regime. Other lofty discussions included reparations for Ukraine, lustration, demilitarization and the creation of a war crimes tribunal.

The idea to rename the document came about spontaneously. Its author, former Russian opposition lawmaker and mastermind behind this gathering, Ilya Ponomarev, initially titled it “The Revolutionary Act.”

For many of the participating deputies, however, especially those with centrist-liberal and conservative leanings, “revolution” carries an unsavory connotation in the context of Russian history. The fact that Ponomarev calls himself a Marxist and often praises the original Bolsheviks likely fueled their anxieties. His fellow deputies would mockingly call him “communist Ponomarev” throughout the four days.

The process for naming the country they believe should emerge from the ashes of the Russian Federation followed. Of the proposed names, which included “Muscovy,” “the Russian Union,” the “Russian Confederation” and “The Eurasian Federation,” the delegates voted for the unobjectionable “Russian Republic.”

A few voiced concern that the name Russia may contain “toxic” associations in the present day but were quickly silenced and overruled.

“It’s not Russia that’s toxic, it’s the actions of our government that are toxic,” one deputy said. “We will create such a government that the name Russia will not carry any negative connotations anymore.”

On the third day of the second congress, another deputy asked to consider changing “Russian Republic” to “Democratic Republic of Russia.”

“There’s already a Democratic Republic of Congo—that’s not where we want this country to be headed!” someone else remarked.

The participants were all Russian politicians once elected to serve in various offices—from municipal deputies in the country’s far-flung regions to members of the national parliament, the State Duma. They emerged from various political parties, some liberals, some communists, some nationalists, libertarians and even ex-members of Putin’s ruling United Russia Party. Some of the delegates traveled from Russia, putting their lives and families at risk.

What unites them, according to Ponomarev, is opposition to Russia’s war in Ukraine, its current regime and imperialistic territorial expansion. To enter the congress, the deputies were required to demonstrate their commitment to the belief Ukraine’s victory must entail a restoration of its 1991 territories, meaning those illegally annexed by Russia, including Crimea.

The first congress, which took place in November 2022, ended in a quarrel. One deputy who criticized Ponomarev had her microphone shut off on several occasions, as did a journalist who asked about the incidents during a news conference. This occasion promised no less drama.

Questions of legitimacy

The primary issue surrounding the congress, much debated throughout its four days, was legitimacy. Often, in such discussions about Russian opposition leaders in exile, the example of the Belarusian opposition leader, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, is raised.

She ran against Belarusian President Lukashenko in 2020, and evidence shows that she won the popular vote, although the government-backed results stated otherwise. Now based in Lithuania, Tsikhanouskaya runs her own opposition government-in-exile, which has been recognized by several Western countries and is believed to be supported by a vast majority of Belarussians.

The story in Russia is different. Since Putin ran for re-election in 2012, no genuine opposition candidate has successfully challenged him or his party, United Russia, in a presidential race. Despite evidence of voter fraud, Putin has also continued to maintain widespread public support over the years.

On parliamentary levels, candidates who ran for parties besides United Russia were often deemed “systemic opposition.” Such characterization suggests the groups were co-opted by the authorities to create a false image of democracy, undermining their legitimacy among opposition members who declined to take part in elections at all.

Members of the jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, one of the most vocal and recognizable Russian opposition blocks currently in exile, even call such politicians complicit in Russia’s war. Yet it was precisely such politicians who comprised the entirety of the congress.

According to Ponomarev’s rules, the fact that they were once voted into office by Russian voters grants them the legitimacy now to take part in the congress and shape the future of their country. By the same token, however, Vladimir Putin might as well be considered a legitimate president who won elections on several occasions. At the Congress, they called him a usurper.

The Russian economist and professor at IE University in Spain Maxim Mironov echoed that sentiment in a tweet following the announcement of the first Congress, saying that “its legitimacy equates to that of Putin’s, meaning none.”

Speaking to me at the Congress, Ilya Ponomarev’s mother Larisa Ponomareva, who was also a delegate, defended herself and colleagues against criticism regarding legitimacy. “They were elected even against all the barriers the authorities put in place,” she said. “Yes, elections in Russia are a very relative concept, but they [the officials at the congress] were still elected with odds stacked against them, and therefore the votes they acquired have high value.” Ponomareva herself served as a senator in Russia’s far-east Chukotka Autonomous Republic for several years (albeit having been appointed, not elected).

Still, many Russians—those living in the country and currently in exile—would struggle to recognize any of the names on the roster of the Congress of People’s Deputies, including its de-facto leader Ponomarev’s. Exiles with whom I spoke about the congress often posed the same questions: Who are these people, and why are they deciding the fate of our country? A parliament of unknown deputies in exile sounds like a circus, no? Isn’t it a bit premature to be drafting a new Russian constitution while the war is still happening and the masses still support Putin?

The competing opposition

For many members of the mainstream Russian opposition in exile, media popularity often replaces past votes as a barometer of legitimacy. The YouTube channel belonging to the jailed and widely popular opposition leader Navalny has 6.37 million subscribers, and its videos garner tens of millions of views. “YouTube is the main instrument of the Russian opposition,” the spokesperson of OVD-Info, a major independent Russian human rights watchdog, told me.

The exiled former oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s channel has just under a million subscribers, and his videos gain hundreds of thousands of views daily.

Khodorkovsky, on the other hand, never took part in any election. Navalny lost a Moscow mayoral election and once declared his candidacy for president before the authorities barred him from participating.

Ponomarev’s YouTube channel “February Morning,” meanwhile, has just under 100,000 subscribers and its videos get no more than a few hundred views. But from 2002 to 2014, he served as a deputy of the Russian State Duma, which, from his point of view, grants him the legitimacy to conduct a parliament in exile.

Ponomarev justified his lack of publicity telling me there has been a “media embargo” on him since 2014, when he was the only Duma member to vote against Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea. That year, he left the country for a business trip and was barred from re-entering. He moved to Ukraine, and while other opposition leaders like Navalny continued to carry out political activities inside Russia, Ponomarev’s popularity waned.

In any case, he does not seem to care. “I need President Zelensky to know about me, not some 10 million Russian nationals, those 10 million Russians will know about me after [Putin’s regime collapses and the transition government assumes power],” Ponomarev said at the closing banquet of the second congress, with a glaze over his deep blue eyes after a downing a few vodkas. With his light beard and eyebrows always raised, there is an amiable quality to him.

Even after the invasion, he continues to spend most of his time in Kyiv. Compared to other Russian opposition leaders in exile, he receives a disproportionately large amount of airtime on Ukrainian media. At the same time, many Ukrainians suspect that mainstream Russian opposition members such as Navalny do not have in mind the interests of Ukraine, a nation that expects Russia to pay a hefty sum of reparations if it is to lose the war. Ponomarev seems convinced his proximity to Ukraine, its people and its government, will ultimately give him the upper hand over his peers.

Do Ponomarev and his transition parliament plan to enter Russia? Yes, on NATO tanks.

Privately, he is critical of his fellow opposition leaders, whom he treats more like rivals. Speaking to me at the banquet, he was unsparing in his criticism of Navalny. “I don’t believe Navalny when he says he wants democracy,” he said. “I believe he wants to be another Putin.”

Yet publicly, he continues to send the message that his congress is willing to open its doors to the mainstream Russian opposition. “I am absolutely inclusive,” he says. One of the first proposals discussed at the congress could grant the opportunity for the likes of Khodorkovsky and members of the Navalny team, who also never served as elected officials in Russia, to take part.

Mark Feygin, a former human rights lawyer who once represented Pussy Riot in a Moscow court and one of the more prominent opposition members to take part in the congress, wrote the proposal. He appeared briefly over Zoom before leaving to attend a virtual event he felt was more pressing. He did not reemerge for the remainder of the three days of the congress despite being one of its key speakers.

Ponomarev took to the podium instead to share Feygin’s document with his colleagues. It proposes an election for current and prospective members of the congress. To legitimize the election prior to conducting the vote, the legislature would gather the signatures of 1 million registered voters, at least half of whom must reside in Russia. Each delegate would then need to gain 100,000 votes to be granted a mandate, the number required to be elected to the State Duma. The process for conducting the vote is still being discussed.

Some deputies proposed creating voting centers in cities where Russian emigres reside, and clandestine voting centers across Russia. Others suggested conducting them online under the oversight of an independent international voting body. The proposal was ultimately approved but not without protest. Some deputies, likely fearing their obscurity would prevent them from getting enough votes, tried arguing against it.

And while the new proposal would open the door for previously unelected opposition leaders to join the congress, many of its current members remain skeptical that they could attract such high-profile people as Khodorkovsky, the former chess grandmaster and opposition leader Garry Kasparov or members of Alexei Navalny’s campaign.

“I don’t understand this snobbism, when other anti-war centers [look down on us]. Such disunity only plays into Putin’s hands,” Sergey Antonov, who, in his 40s was one of the younger delegates at the Congress, told me in the lobby of the business center where the same lounge piano tune played on repeat for the four full days.

In recent years, Antonov worked as a campaign manager for parties that ran against United Russia in the country’s Udmurtia Region east of Moscow until he fled to Spain in 2022. He now runs his own breakaway opposition party in exile, Citizens of New Russia.

An honorary guest of the congress with whom I spoke, the Russian filmmaker Grigory Amnuel, told me the opposition in exile “continues to repeat the mistakes of their predecessors,” referring to the emigres who fled the Bolsheviks a century ago. “We agree on who is the enemy, but we can’t agree on the reality that we need to defeat the enemy before deciding who is the greatest benefactor of the victory,” he said.

Other journalists present at the congress told me they had encountered Amnuel buzzing around similar opposition forums and conferences, including the Free Russia Forum that takes place in Vilnius. In a gentle, articulate manner, typical of older Russian intelligentsia, he explained why he supports such initiatives. “Putin’s regime is stumbling, but for it to fall, it needs an alternative,” he said. “If the regime falls but people who have no political expertise assume power, the situation could become even more turbulent.”

In late March, Ponomarev said on Twitter that Khodorkovsky had invited the congress to take part in a meeting between opposition politicians in exile at the end of April. Perhaps the former tycoon is noticing potency in Ponomarev’s strange ways.

Ilya Ponomarev – revolutionary or political grifter?

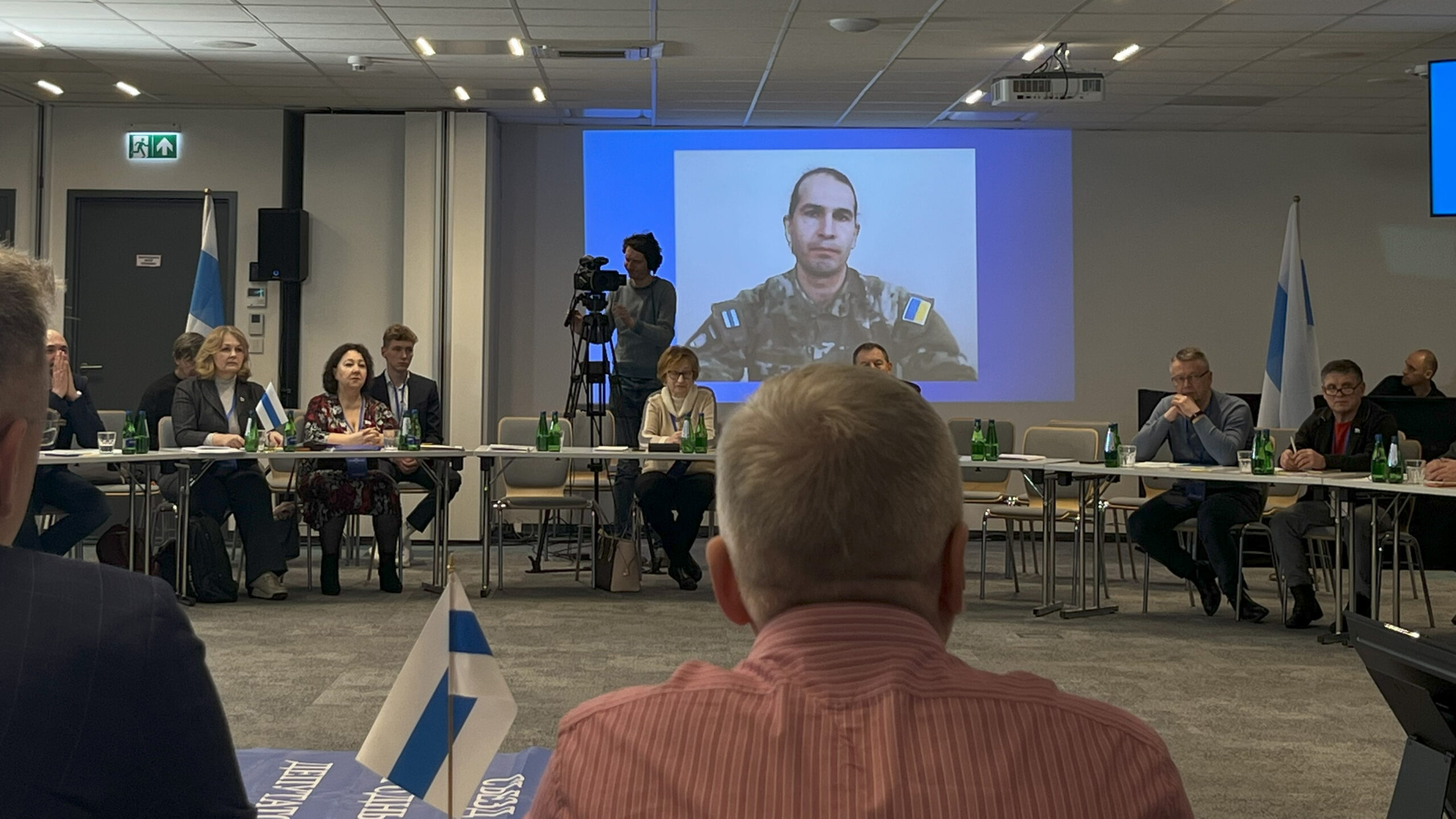

Like something out of a campy scene in a Pierce Brosnan-era James Bond film, a man sporting a camouflage jacket with his hair pulled back in a greasy ponytail appeared over Zoom on a large projector during the opening hours of the congress to give a prefatory speech. Introducing himself by only his codename, “Caesar,” he said he was the head of the Freedom of Russia Legion fighting on the side of Ukraine and was allegedly calling from Bakhmut, the Ukrainian city under heavy siege. Ponomarev later described Caesar to me as a former Russian nationalist who defected.

The Freedom of Russia Legion is reportedly composed of Russian soldiers who are fighting alongside the Ukrainian army. Ponomarev’s decision to include Caesar as a keynote speaker echoed his recurring calls to wage an armed partisan war against Putin’s regime.

But his advocacy of violence has helped marginalize him from the mainstream opposition. In August 2022, Ponomarev claimed a clandestine partisan organization, “The National Republican Army,” was responsible for the Moscow car bombing of Darya Dugina, the daughter of the far-right Russian public intellectual Alexander Dugin.

Immediately after the incident, Ponomarev published the group’s alleged manifesto, for which independent Russian journalists and scholars called him a “grifter.” He was subsequently barred from taking part in a planned meeting of prominent Russian opposition members organized by Kasparov and Khodorkovsky.

Following another assassination, of the pro-Kremlin blogger Vladlen Tatarsky on April 2, 2023—who died after being handed a statuette rigged with an explosive device in a St. Petersburg coffee shop—Ponomarev again invoked the National Republic Army. Commending the attack, he claimed he had been aware it would take place in advance.

Khodorkovsky, meanwhile, condemned Tatarsky’s murder as an act of terrorism, calling its orchestrators “sick people” for putting innocent lives at risk.

Ironically, Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, blamed the attack on Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation and the Ukrainian authorities. Members of Navalny’s campaign vehemently denied the allegations, and observers began to speculate that the Kremlin will use the accusation as pretext to carry out even harsher repressions against any form of domestic opposition.

But on April 5, the English-language Kyiv Post published an article raising new allegations that Ponomarev may have known who was behind the attack. According to the article, he had contacted one of the paper’s journalists before the explosion to tell him that another “Putinist enemy” would soon be killed.

Ponomarev’s bent for action and calls for violence are not new. In 2012, during a series of major Moscow protests against Putin’s re-election that year, he was already advocating for armed resistance against the regime. Until their eventual suppression, the “Bolotnaya Protests” as they came to be known, seemed to participants like a pivotal moment in Russia’s political trajectory.

In a documentary produced by the late filmmaker Alexander Rostorguev, he is featured driving a car with a prominent opposition socialite named Ksenia Sobchak. After Ponomarev declares that the Russian opposition needs to “seize the power now” and “hang them [Putin and his associates] by their ankles,” a debate between the two ensues.[i]

Repelled by the idea of armed resistance, Sobchak responds that violence would only pave the way for an even more dictatorial regime. “Look what happened in 1917, they had a grand old time, didn’t they?” she says in reference to the Bolshevik Revolution.

“But it worked, it worked, didn’t it?” Ponomarev quips in response. “This is a good example of an effective tactic for assuming power; we need to study it.”

“I physically feel like time is ticking away,” he adds. “This running around on town squares [protesting] isn’t close to me. I want to actually build a new country, and I have ideas about how to do that.”

While many find Ponomarev’s proposed schemes questionable at best, his supporters and associates do not doubt his political and business acumen. Born into a family of politicians, he began his career in the 1990s working in the IT sector of Yukos, Khodorkovsky’s major oil company that was taken over by the state.

In a paradoxical turn, Ponomarev later joined the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, serving as chief informational officer from 2002 to 2007. In the 2010s, he became involved with the prominent Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, part of what the government wanted to turn into a Russian Silicon Valley at a time when Russia sought to reclaim its mantle as a technological superpower. His marriage of technological development with Marxist values have earned him the characterizations “neo-Trotskyite” and “unorthodox leftist.”

“He was born into a family of real politics, not television politics, but real politics,” Amnuel said. “His intellectual horizon is much broader than any other person who comes into politics, but now that the level of real, genuine politics in Russia has been reduced to zero, there is no place for him there.”

A deputy from the Nizhny Novgorod region, which straddles the Volga River and sits just east of Moscow, praised Ponomarev for his willingness to welcome politicians of various political leanings. He asked to remain anonymous as he continues to live in Russia and says he worries about the safety his children. “Ilya is important because he doesn’t care what your views are, or whose interests you support,” he said, his voice slightly drowned out by the piano player at the banquet. “The important thing is that, first, everyone [at the congress] recognized Russia is the aggressor, that it attacked Ukraine, that it destroys cities and kills innocent people.”

The deputy once represented a far-right nationalist party called Rodina, created by the Kremlin to draw votes away from other nationalist groups. He had a tattoo on his index finger that a fellow journalist from the independent Russian outlet Sota Journal told me may indicate he had served time in prison.

A motley crew of politicians

Hours and hours of the congress were devoted to the discussion of “decolonializing” Russia. According to the agreed-upon proposal, once the “transition parliament” assumes power, all federal politics would be halted for a year while voters across Russia’s regions begin the process of electing local officials. They would conduct referendums asking their constituents if they would want to join the Russian Republic or create autonomous republics of their own with sovereign governments. The Russian Federation currently comprises 21 territories that officially qualify as “republics.” Many are populated by their own indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities with their own languages, cultural traditions and religions.

For hundreds of years now, indigenous peoples across Russia’s present-day republics have fought to preserve their cultural and linguistic identities against colonial Russification policies. In Buryatia, which borders Mongolia, many locals speak a dialect of Mongolian and practice Buddhism. Dagestan in the North Caucasus is Russia’s most linguistically diverse republic with 14 official languages belonging to the Turkic and North Caucasian language families. Minarets rise from Dagestan’s centuries-old stone villages.

Although the congress devoted much attention to putting mechanisms in place for decolonization and restoring autonomy to republics, there was a glaring absence of deputies representing the country’s ethnic minorities. When I asked Ponomarev about whether he saw that as a problem, he said there were plenty of “regionalists” present.

One such “regionalist,” Pavel Mezerin, an ethnic Russian, is the coordinator of Free Ingria, a marginal separatist movement that advocates the former imperial capital St. Petersburg and its surrounding territories should separate from Russia to restore the historical Ingria region. A longtime leftist activist I spoke to from St. Petersburg told me that members of Free Ingria would yell far right and racist rhetoric at political rallies.

Members of Russian nationalist parties were also present at the congress, where they formed a vocal bloc of their own. On numerous occasions, they raised concerns about the need to address Putin’s “Islamification” of Russia. With several majority Islamic republics, Russia has the largest Muslim population in Europe, and new mosques continue to prop up across its major cities. Russian nationalists are critical of Putin’s proximity to and empowerment of Ramzan Kadyrov, the dictator of the Chechen Republic who is of Muslim faith.

At the final banquet, I was seated at a table with all the nationalists, a crew of stocky men. One sported a flat-top military haircut. Their faces already reddened by wine, they raised their vodka glasses and cheered, “Brothers, nationalists––for us!” I asked whether they considered Putin a nationalist, to which they resoundingly responded by calling him a “communist, internationalist, chekist [member of the original Soviet secret police]!”

For the regionalist-nationalists, Putin’s KGB origins, his perceived attempts to preserve Russia as a multiethnic monolith, and apparently Soviet-like expansionist ambitions do not sit well.

But thanks to Ponomarev’s drive for inclusivity, nationalists were just one of several factions at the congress. Representatives ranged from social democrats, like the veteran politician Gennady Gudkov who appeared over Zoom, to centrist conservatives such as Andrey Illarionov, who served as Putin’s main economic adviser during his first and second terms. Communists and libertarians were present as well.

A liberal deputy named Elena Lukyanova, who was able to appear only through Zoom, was among the more savvy politicians. Her extensive law background gave Ponomarev confidence to entrust her to be one of the architects of the new constitution. But she found it tough going. At one point during an endless cycle of debates regarding a key point in the document, she let out a big sigh of frustration. “Do whatever you like with this constitution,” she said in a defeated tone.

The fact that the participants had extremely varied degrees of political expertise often made the proceedings difficult. The representation was as much horizontal––nationalists to communists––as the hierarchy was vertical––ex-Duma members to former city council officials. Members like Ponomarev and Gudkov had served over a decade in Russia’s State Duma. But there were also regional deputies whose biggest political contributions may have been the approval of the construction of a bridge that connected one rural village to another.

The mixed experience presented the biggest hitch for observer Amnuel. “The combination of municipal, local and state deputies is difficult,” he said. “Local deputies usually deal with very specific [county] issues. Here they have to work on documents of an enormous caliber, designed for a population of 140 million, not 140 people.”

How to assume power?

One of the congress’s primary goals was to propose mechanisms to prevent the usurpation of authority, “another Putin” from coming to power. Such mechanisms included, but were not limited to, the liquidation of the FSB, and the reduction of the president’s role to a symbolic one, or the presidency’s complete abolishment.

Yet one of the proposed measures appeared quite authoritarian: the closure of Russia’s borders during the first year a transition parliament would assume power. The idea is to bar seditious forces from arriving in the country during a state of flux, and to prevent those complicit in Putin’s war from escaping before facing legal consequences. It could also be used to prevent Ponomarev’s opposition rivals such as Khodorkovsky from entering the country, the journalist from Sota speculated.

But do Ponomarev and his transition parliament plan enter Russia in the first place? Yes, “on NATO tanks,” according to a recurring joke at the congress.

Based on my conversation with him at the banquet, Ponomarev seems convinced that if and when Russia suffers a military defeat at the hands of Ukraine, the depletion of its army and political infighting between current elites would open a window of opportunity. Ponomarev’s alleged partisan fighters and members of the Freedom of Russian Legion would march to the Kremlin with Ukraine’s backing.

I asked Ponomarev if he fears Russians may take issue with his comments that Zelensky’s opinion of him matters more than that of the people he intends to represent. “I don’t give a fuck,” he responded. “I don’t need the legitimacy [of Russian nationals], I need the army, because we’re coming to power with bayonets,” he told me at the banquet, clarifying that his main goal is to help Ukraine win and then arrive in Russia as a representative of “the victorious side.”

Dinner––a very generic spread of cured meats, cheeses, salads and salmon––was already consumed at this point. The music was getting louder, as were the toasts. Ponomarev produced a smile after almost every sentence, which was quite strange given the gravity of his words. “This will be our source of legitimacy,” he added, “mandated by the anti-Putin, global coalition. We’re going to be an occupational government, not an elected one.” Russian voters “will not be players in this change.”

However, he was quick to add that after the transition period, Russian nationals would be re-granted the right to elect their future leaders. At that point, Ponomarev said, he would resign from politics, slipping behind the scenes to work for a new supreme court.

He proceeded to criticize his Russian opposition peers for what he sees as their shortsightedness. “They won’t win Ukraine’s support because they’ve already said too much,” he said. “They’re trying to act through the West, to pressure Ukraine through their allegiances to the US, to Brussels…” He paused. In the background, the woman pianist for the banquet began singing “Chernova Kalina,” a Ukrainian patriotic march banned in Crimea by the Russian authorities after its illegal annexation.

Ponomarev got up from the table and walked over to the pianist, singing along. “Marching forward, our fellow volunteers, into a bloody fray; For to free our brother Ukrainians from the Muscovite shackles!” He belted out a lyric in Ukrainian.

After the song ended, he returned to the table. “How’s that for your material, the perfect note to sign off on?” he said with a grin before walking away to continue celebrating.

At the start of our conversation, I had asked what gave him such strong conviction that the future would take shape as he envisions it. “Because we feel it, that’s how it will happen,” he responded. “Politics is about spirit, it’s about will, it’s about belief and about calculation, which is secondary, but it’s also important.”

A few weeks later back in my base in Tbilisi, I relayed the conversation to the Moscow theater director Vsevolod Lissovsky, who recently fled Russia from fear of persecution. “I often joke that the day some Ilya Ponomarev-type character storms Moscow on Ukrainian tanks is the day I begin digging my grave,” he said. “Such a person can be worse than Putin.”

Endnotes

[1] The documentary filmmaker Alexander Rastorguev was killed in 2018 by unknown assailants in the Central African Republic while filming a documentary about the Wagner Group, the same “private” paramilitary organization that is currently fighting for Russia in Ukraine.

Top photo: The nationalist bloc voting on an amendment