TBILISI — When the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski visited this city in 1990, a year before the collapse of communism, he noticed a melancholy ritual in which locals sat on the steps of what is now the Georgian parliament on central Rustaveli Avenue, holding photographs of loved ones killed by Soviet soldiers during pro-independence protests in 1989.

“These women, holding before them photographs of their deceased children, want people to stop, to take these photographs into their hands, to gaze at the young, sometimes astoundingly beautiful faces,” he writes in his book Imperium, an account of the Soviet Union on the brink of collapse, adding, “in Georgia mourning is celebrated openly, it is an act of public and heartrending demonstration.”

An abstract monument for the victims of the anti-Soviet protests was later erected in the place where the women sat with their photographs. Today, the tradition of public mourning continues: photographs of the now-34 Georgian volunteers who died fighting in Ukraine adorn the same monument.

With over 1,000 members, the Georgian Legion is the largest foreign faction fighting on the side of Ukraine. The photographs serve as a vivid reminder to both locals and newly arrived Russians in Tbilisi that the war is also Georgia’s war.

“If Germans feel the war at a 5 out of 10-point scale, the Poles at a 7 and Americans at a 3, then we feel it at a 10,” says Nodar Rukhadze, founder of a Georgian pro-European integration activist collective named Shame Movement. “I don’t think anyone in this world understands what the Ukrainians are going through more than we do.”

Georgia shares its entire 556-mile border along the Caucasus Mountains with Russia, a country roughly 245 times its size that illegally occupies 20 percent of Georgia’s internationally recognized territory. To its west, some 600 miles of the Black Sea separate this country from the missile onslaught in eastern Ukraine. Georgia was the last country to suffer a full-scale Russian invasion, in 2008. In the 19th century, it was a colonial subject of the Russian Empire, and in the early 20th century, the Red Army forced Georgia’s accession into the Soviet Union.

Some 90 percent of Georgians say they perceive Russia to be their greatest political threat, according to an opinion poll conducted in the spring. If the Kremlin’s behemoth military force succeeds in Ukraine, some Georgians worry, their country could again be next.

“This is a battlefield that Georgians follow closely and perceive as partly their own; they may see it as a preamble to stir up conflict here,” says Nutsa Batiasvhilli, professor of anthropology and dean of the graduate school at Free University Tbilisi.

Shame on the Dream

A military assault prematurely ended Nodar Rukhadze’s 2008 summer visit to his grandparents’ home in the Black Sea port of Poti when he was 11 years old. His father drove him back to Tbilisi two days before Russian forces completely surrounded the town.

“We’re lucky to have only experienced [the Russo-Georgian] war for 12 days; the Ukrainians have been enduring this for almost a year now,” Rukhadze tells me in the apartment-office of his civil society organization a stone’s throw away from parliament. With his near-perfect English and American Gen Z intonations and neologisms, he wouldn’t seem out of place running his organization from a Brooklyn brownstone instead of a 19th-century Tbilisi apartment.

He founded the Shame Movement along with a group of fellow activists in 2019 to channel the widespread public outrage many Georgians felt when their government invited a Russian official to speak in parliament. The official, Sergei Gavrilov, sat in a chair reserved for Georgia’s heads of parliament––an act Rukhadze and his peers saw as a desecration of a main symbol of Georgia’s democratic tradition.

The Shame Movement was named “in reference to the feeling of disgust that we felt for our government when it greeted this Kremlin politician with open arms,” Rukhadze tells me.

In the weeks following the visit, the organization spearheaded a series of mass protests that drew up to 15,000 people and resulted in the resignation of parliament’s speaker, Irakli Kobakhidze. For a city of just over 1 million, the turnout was of no small significance.

Along with the Shame Movement, critics of the ruling party, which calls itself “Georgian Dream,” are convinced its founder, the billionaire businessman Bidzina Ivanishvili, is a puppet of the Kremlin who maintains de facto control despite no longer holding office. Critics liken the party to the notoriously corrupt regime of the Kremlin-aligned former Ukrainian Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, which governed the country before the pro-Western 2014 Euromaidan Revolution.

Ivanishvili amassed his wealth during Russia’s 1990s privatization period and purportedly continues to maintain close ties with Russian oligarchs. He served as prime minister in 2012-2013 and claims to have recently retired from public life to focus on philanthropy. In April 2022, two months after Russia had invaded Ukraine, a phone call between him and the Russian oligarch Vladimir Yevtushenkov, who is sanctioned by the West, was leaked to the public.

While the specifics of the conversation are difficult to decipher, its overtly friendly tone and discussion of collaborative dealings raised suspicion among Ivanishvili’s critics. In the call, he refers to Georgia’s current prime minister as a “young [person] who will take care of everything.”

Following the leak, Ukrainian politicians repeatedly called on the West to sanction the Georgian billionaire. Some members of the Georgian government downplayed the conversation, calling it a “fake”; others claimed it amounted to nothing more than a harmless business call.

Prior to his ostensible departure from politics, Ivanishvili appointed several of his personal acquaintances to the highest levels of government, adding fuel to theories that he continues to exert political influence operating as the party’s gray cardinal.

Georgia’s current prime minister, Irakli Gharibashvilli, held executive positions at Ivanisvhili’s companies prior to his foray into politics. The country’s infrastructure minister, the head of the security services and the finance minister also all worked for the same companies, most notably, Ivanishvili’s family charity the Cartu Fund.

The current Interior Minister once served as the billionaire’s personal bodyguard, and the Health Care Minister directed a private hospital financed by the Cartu Fund.

“We call this state capture,” Rukhadze tells me.

Rukhadze and his colleagues also say their government is exhibiting behavioral patterns resembling that of an authoritarian state. A 2021 leak revealed the Georgian Dream tapped phone conversations of opposition parties, ambassadors and civil society organizations like Shame.

Rukhadze says the secret service follows the group “all the time.”

Meanwhile, the ongoing imprisonment of former President Mikheil Saakashvili, who ruled the country during the 2008 Russo-Georgia war, has called into question the independence of the judicial system. Recent photographs of Saakashvili show a frail, ailing man––a skeleton of the once robust showman who rid Georgia of its petty corruption.

Before the Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, Saakashvili’s United National Movement held power from 2004. He rose as a leader of the Rose Revolution, a liberal, anti-corruption movement that swept away the old regime of the former Communist leader Eduard Shevardnadze in a bloodless political coup.

The early years of Saakashvili’s tenure brought sweeping economic reforms that boosted the country’s moribund GDP, and brought a severe crackdown on rampant organized crime and an end to police corruption. Leaning on his close relations with the West, Saakashvili sought to transform Georgia into a prosperous oasis of the former Soviet Union.

But alignment with the West did not bode well for his relationship with Vladimir Putin, and in 2008, tensions between the two countries spilled over in the Russo-Georgia war. The two weeks of fighting following Russia’s invasion resulted in Georgia’s loss of the Moscow-backed breakaway republics Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Later in his tenure, Saakashvili began to fall out of favor with the Georgian public. The progressive reformer became seen as a hotheaded autocrat who resorted to violence in his bid to rid the country of corruption. After his election loss in 2012, the newly elected Dream Party sought to press criminal charges against him, prompting him to flee overseas. But in 2021, convinced of his political prowess, he illegally returned to Georgia in a sea-cargo ship, and called on the public take to the streets.

The Georgian authorities immediately arrested him on charges of power abuse related to an alleged cover up of violent acts against a lawmaker. Members of the Georgian opposition believe Saakashvili is a political prisoner who has yet to undergo a free trial. But some believe his imprisonment is justified.

Speaking to me in a coffee shop in Tbilisi, labor organizer Sopo Japaridze says that his brutal crackdown on corruption led to the deaths of many innocent civilians, with police officers often acting with impunity. She tells me a story of how a friend of her brother’s was shot to death in Tbilisi by police officers after being pulled over for a traffic violation in 2009.

Japaridze, who is in her mid-30s, spent most of her life in the United States, audible in her South Brooklyn accent. In her free time, she interviews various scholars for her podcast “Reimagining Soviet Georgia,” in which she attempts to extrapolate positives from the Soviet experience. She also harbors strong opinions about her country’s current politics.

“Saakashvili became an unhinged narcissist, and his party were totally reckless in their later years,” she tells me. “The democratic backsliding would be worse under Saakashvili’s leadership; I am certain my union would not exist if he were president.”

Shalva—whose name I’ve changed on his request—a tour guide who drove me around the northern mountainous region of Kazbegi, tells me that while he believes Saakashvili deserves to be in jail, “the one good thing that he did was get rid of crime and bribery.”

Swerving towards the Russo-Georgian border between towering snow peaks, he tells me how before Saakashvili’s tenure, he would use the Georgian Military Road to smuggle contraband between the two countries. Border officers were easy to bribe back then.

“Now I drive Russian draft dodgers and tourists on this road,” he says with a smirk.

The new Russian invasion

Georgians’ visceral reaction to the war in Ukraine has spilled into their mixed perceptions of recently arrived Russian emigres. Tbilisi became a hub for those fleeing their country for political and economic reasons even before the start of the war in February. The Kremlin’s declaration of mobilization in September brought an additional several thousand more. Some 222,274 Russian citizens entered Georgia in September alone, according to the Interior Ministry.

While opinions among locals vary, many young people in Tbilisi are angry their city has become a haven for whom they see as their former colonizers, many of whom work remotely and receive salaries significantly higher than the local average. Rent in the city has soared to unprecedented heights, causing many Georgian students to face evictions. Several social media groups created for Georgian students to find housing forbid use of the Russian language, while some landlords explicitly state they do not rent to Russians.

Anthropology professor Nutsa Batiashvilli says her own students harbor especially negative feelings about the second wave of emigres who came not necessarily because they oppose the war but because they fear for their own safety.

Young Tbilisi locals are also unhappy about what they perceive to be ignorance and “colonial attitudes” that some of the second-wave Russians bring. “We are happy to let in queer activists, opposition journalists and repressed ethnic minorities,” an activist named Mariana Dolidze tells me. “But those Russians who come here and expect all of us to reply in their language or who say they do not care about politics are not welcome.”

Others agree. “Many act like this is their second home, which could create conflict with locals,” says Irakli Khvadaginia, historian and board director of SovLab, a Georgian human rights organization devoted to rehabilitating victims of Soviet repression.

I tell Khvadaginia that such an opinion may suggest that the Russian expats I associate with—activists, journalists and creatives––comprise an “expat bubble,” much more attuned to their country’s imperialistic relationship with Georgia and try as often as they can to open conversations with locals in English rather than Russian, the common lingua franca.

Some Russian expat Telegram groups even recommend newcomers open conversations with “Kamardjoba [hello in Georgian]; do you speak English; ily vam udobnee po Ruski? [or are you more comfortable speaking in Russian?]”

If younger Georgians grew up with English as their second language and consume primarily Western music and American television, most older Georgians still speak Russian, and their cultural upbringing was colored by Russian-Soviet films and music.

That is why many older and working-class Georgians say they prefer Russian immigrants to others because of a perceived familiarity, sociologist Batiasvhilli says. “In the eyes of these respondents, Russians are neighbors with whom we shared a common space and who would not disrupt Georgian cultural integrity,” she says.

That sentiment is more visible beyond Tbilisi’s city center.

In a hole-in-the wall restaurant nestled in the valley town of Stepantsminda, 70 miles north of Tbilisi near the Russian border, where Ukrainian flags adorn the walls, the restaurant’s owner, a middle-aged local who asked to be referred to as “Giorgi,” tells me he believes it is his duty to “educate” the Russian newcomers. “Beyond the money they bring us, we have a humanitarian duty to accept them,” he tells me. “If they spend a just year outside their repressive country, with access to more information and different opinions, maybe their minds will change.”

“By accepting military deserters, we are also taking away from the manpower of the Russian army,” he adds.

On the marshrutka––the Soviet-era microbus service still commonly used in Georgia––that I took back from Kazbegi to Tbilisi, the driver put on a mix CD featuring several Soviet-Russian classics. The faces of the only two Russian passengers––a quiet, young couple who sat timidly in the back––suddenly lit up when they heard the Russian rock band Mashina Vremeni blare from the speakers.

In Tbilisi, some local businesses are also benefiting from the new immigrants. Sopo Japaridze’s own family runs a restaurant that was on the verge of bankruptcy because of the Covid-19 pandemic. The influx of Russian customers halted the restaurant’s closure.

“They have brought Tbilisi’s [service economy] back to life, it was dead after the pandemic,” she tells me as we sip Americanos in the upscale Vakke neighborhood where studio apartments can rent for well above $1,000 a month.

“I now see ads for salsa dancing, samba dancing classes,” she says. “The Russian immigrants have brought this middle-class culture that just didn’t exist in Tbilisi before because people were not as well off.”

Cultural segregation or ‘We grew up in darkness’

While mainstream, tourist-oriented restaurants, bars and cultural spaces profit from the influx of immigrants, Georgians operating more independent establishments worry that the influx of Russians may hijack Tbilisi’s growing counterculture scene. Many of the Russians have money, after all, and some of those from Moscow and St. Petersburg an acumen for running their own restaurants and nightclubs.

A noticeable number of Russian-owned cocktail bars, independent bookstores and coffee shops, vegan restaurants and multidisciplinary art spaces have already popped up across Tbilisi since the start of the war.

While some of the new Russian venues take great efforts to politicize and assimilate their clientele through lectures on politics and screenings of Georgian films, the Russian-speaking crowds and often overpriced nastoiki, or Russian vodka infusions, deter young Georgians from frequenting such places. Cultural segregation is increasingly visible in some areas of the city center, and the sleek Russian establishments may accelerate gentrification.

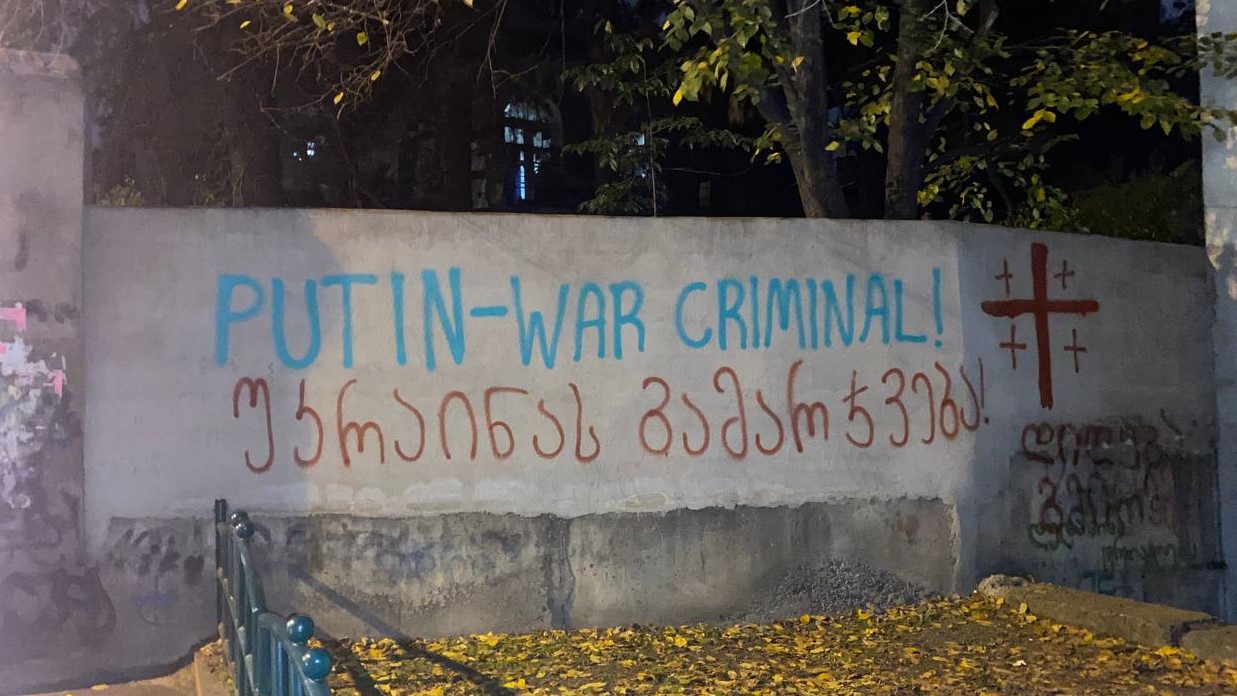

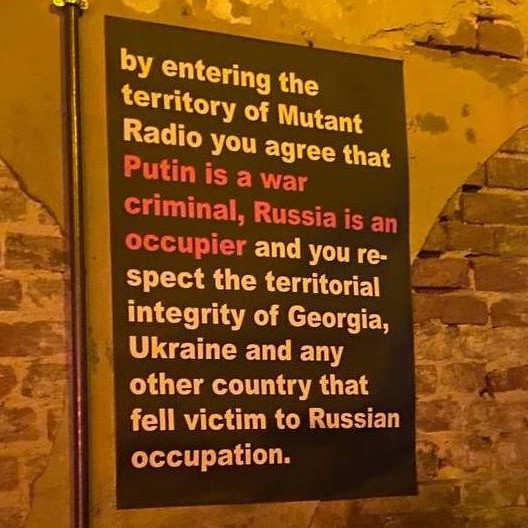

Several local restaurant and bar owners have begun demonstrating their dissatisfaction by forcing Russian customers to sign waivers recognizing their country’s occupation of Georgia’s territories. Others ban Russians entirely.

In a former factory building that menacingly peers over the eastern bank of Tbilisi’s Mtkavri River is a Georgian-owned multidisciplinary art space and underground club. Its name, Tbiliorgia, is a play on the names of its home city and country.

The resulting inclusion of the Georgian word for orgy, orgia, also symbolizes its owners’ mission to open their doors to a diverse mélange of Tbilisi’s subcultures. “We want this space to shine with all the colors of the rainbow,” says Sandro, one of the club’s founders, who asked that his last name not be used.

The only people for whom the doors remain closed are Russians.

“We think we are doing them a favor,” he tells me behind a screen of cigarette smoke as we sit on dusty couches in the club’s upstairs back room. “If the bouncer tells them they can’t come in, they may stop to think and ask themselves why,” another cofounder, Luka, says.

Compared to the recently arrived Muscovites who typically wear new, clean, Russian-brand clothing, Sandro and Luka dress as if they’ve emerged from a 1990s American hip hop video: secondhand down jackets, hoop earrings, cargo pants and worn sneakers. Asked what it would take to change their minds about letting Russians into their club, they tell me they would need to see emigres protesting their government’s war on the streets “every single day.”

“Instead, they just come here to relax, eat, drink and shit all day!” Sandro says, slamming his fist on a table.

The two longtime friends were born in Tbilisi in the 1980s, when Georgia was still part of a Soviet Union on course for dissolution. The collapse hit the country hard. The GDP plummeted by 75 percent, the biggest peacetime economic drop in world history, and the country became a playground for both Russian and Georgian organized crime. A brutal civil war gripped the nation from 1991 to 1993.

As children, Sandro and Luka played with bullet casings they collected on the streets. With the country suffering from an energy crisis, at one point two hours of daily electricity was the only time they could avoid use of kerosene lamps.

“We grew up in darkness,” Sandro tells me. “Darkness in our homes, and darkness in the streets [with] gangsters with Kalashnikovs.” As millions across Ukraine recently celebrated their holidays under candlelight and without heating, such memories feel especially poignant now.

When Russia invaded Georgia in 2008, Sandro and Luka were of military age but dodged the draft for medical reasons. Sandro’s father still took him and his friends to a field outside the city to teach them how to fire assault rifles. “They [the Russians] were just a few kilometers away,” Sandro says. “We needed to be ready to fight.”

Sandro and Luka now associate Russia with the war, criminality, oligarchy and exploitation that plagued their childhoods. “We grew up with this shit that the Russians brought, these guns, bullets and gangsters,” Sandro says. “And now they are doing this shit again,” he adds about the war in Ukraine.

Their insistence on keeping Russians away from their club also stems from a desire to promote a local culture of their own untainted by foreign influence. After speaking to me at their club, Sandro and Luka took me along on a talent-scouting mission at the release of a young local musician’s new hip-hop album.

A 20-minute drive from the overwhelmingly Russian-speaking hillside neighborhood of Sololaki where prices continue to rise lies the working-class neighborhood of Didube. In a small garage nestled between the towering Soviet high rises, Didube Records produces music by young artists from the neighborhood.

Under the fall night sky, a group of some 40 Georgians––college students and young parents with children––huddle together in the garage to celebrate the new album. Between each song––a contemporary cross between soul and hip-hop music––the artist, Deeda, spoke about the themes and inspirations for her music. The audience chuckled and clapped, embracing her artistry without critique or judgement. Not a word of English or Russian was spoken. One man tended to a trash can fire that provided warmth and light for the intimate occasion.

“For so many years we’ve grown up on music that came from the outside world,” the label’s founder, pictured above in a red sweater, tells me as she hands me a glass of homemade wine poured from a plastic jug. “Now we want to create something for ourselves––a celebration of our own culture.”

European Ambitions

The oldest found scriptures of the Georgian language date back to the 5th century AD. It belongs to the unique Kartvelian family of languages spoken exclusively in the South Caucasus, which bears no similarities or overlaps with neighboring languages.

The preservation of both language, autonomy and strong Christian identity—Georgians have observed Orthodox Christianity brought from Byzantium since the 1st century—in the face of Ottoman, Iranian and Russian imperial subjugation, serve as testament to Georgia’s resilient national narrative. At the core, says the anthropologist Nutsa Batiasvhilli, is an identification with the greater European world.

Today, 75 percent of Georgians say they would welcome their country’s integration into the European Union, according to recent opinion polls. The pursuit of EU membership is even listed as a demand in Georgia’s constitution.

For most Georgians, Putin’s anti-Western propaganda that Europe, with its tolerance for LGBTQ rights, represents a decay of traditional and religious values, also fails to resonate. “Christianity is not really practiced in a religious way [here], it’s celebrated in a secular way, which is inherently tied to our national identity,” Batiasvhilli says.

“Georgians don’t see how being a part of the European Union can disintegrate their social fabric in the way Russian propaganda claims it could,” she adds. “Georgian social traits are too deeply seated to be eradicated by European Union membership.”

European accession would also offer security guarantees. “We believe that Russia is an existential threat to our country, and the only way for us to survive as an independent state is to be in alliance with European nations,” Nodar Rukhadze of the Shame Movement says.

Georgia applied for European Union membership shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, but the opposition, as well as members of the European Commission, have claimed that the Dream Party is deliberately dragging its feet meeting the qualifying demands. One calls on the government to pardon Saakashvili. Another entails “de-oligarchization,” which would mean the government’s full break with Bidzina Ivanishvili.

Regardless of whether the Georgian Dream meets these demands, the European integration process would require major structural and economic changes and take years to accomplish.

‘City of peace’

Underneath the blankets of Christmas lights strewn across Tbilisi’s central boulevards, posters can be spotted advertising the slogan “City of Peace.” It was chosen by the city council to represent Tbilisi during holidays. But it did not resonate well with the opposition, who felt it a slight both against Ukraine and themselves.

They have been especially critical of the Dream Party’s lack of clear condemnation of the war. In response, the ruling party’s members have referred to their opponents, including Saakashvili’s National Dream Party, as the “party of war.”

Still, some believe that at a time when their neighbor to the north is so volatile, a position of neutrality may be the best course. Sopo Japaridze rejects the claims that the Dream Party is somehow doing the Kremlin’s bidding. “They’re just a party of pragmatists; and Ivanishvili, just like any billionaire, is not ideologically driven,” she tells me.

Debates about Georgia’s stance on the war continue to rage on. In early December, the Dream Party’s chair even threatened to strip the legionnaires fighting for the Ukrainian army of their Georgian citizenship. Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili called them victims of “immoral populism.”

But the success or failure of Ukraine’s army, helped by the Georgian legionnaires, will undoubtably play a major role in determining the future of Georgia’s political, economic and social landscapes.

The future for Russians in Georgia

Most of the Russians from Moscow and St. Petersburg I’ve spoken to here view Tbilisi mainly as a waypoint. To where, however, remains to be seen.

Some are holding out hope that a return to Russia will still be possible. Others talk about an abstract next destination, like the greater European world, or even South America. Places where they can be further from the conflict and possibly integrate into societies they deem more stable. But regardless of longer-term wishes, many Russians continue to apply for Georgian residency permits, even for the short term.

Uncertainty persists here, especially given the shiftiness of the current ruling party’s stance on Russian immigrants. In late December, reports began to surface that several Russians living in Georgia were being barred from accessing their Bank of Georgia accounts. While the bank’s representatives never gave an official reason, and the news was quickly swept under the rug, such incidents cause panic in émigré circles, reminding them that they live in a world of flux and instability.

Like the central characters of Anton Chekhov’s plays, Russians in Georgia continue to live in a state of disquiet and ambivalence, many of them passively waiting and hoping that external circumstances will somehow shift in their favor.

Top photo: Russians outside a Russian-owned coffee shop in the Vera neighborhood