TBILISI — The Georgian cab driver, who appeared to be in his 60s, clearly had not heard the news. Upon arriving at my destination—the Section of Russian Interests at the Swiss Embassy in Georgia, which stands just across from the Ukrainian Embassy on Ilia Chavchavadze Boulevard, a busy main thoroughfare—he noticed a large crowd in front of its tall metal gates.

“What is this, some demonstration?” he asked in Russian.

“Yes, a demonstration,” I responded.

“And who are they?” he followed up with curiosity.

“Russians,” I said.

Choking in disbelief of what I was about to say and nervous about revealing sympathy for a man generally disliked across the Caucasus, I blurted out: “Navalny is dead!”

The driver paused, his eyes pensively staring back at me through the rearview mirror. Then, as if coming to the realization, he muttered: “They killed him after all… Sad… Tragic…”

On the morning of February 16, the Russian authorities had announced that the opposition leader Alexei Navalny had died in prison. For the teary-eyed emigres gathering in front of their country’s diplomatic representation—which had downscaled operations after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War—it was an unequivocal tragedy.

Navalny’s defiant will to endure in the face of near-fatal poisoning and captivity gave a kernel of hope and inspiration to the Russian exile community. Whether his death resulted from health issues brought on by the murder attempt in 2020 and squalid prison conditions inflicted on him later, or whether the authorities had indeed outright slain him matters little to his supporters.

As the driver pointed out, the Kremlin had killed Navalny one way or another, extinguishing any prospects for political change or alternative leadership in the near future.

Still, many critics of President Vladimir Putin’s regime hope Navalny’s death will foster unity and determination in the democratic, antiwar opposition-in-exile. Just a few weeks earlier, a surprising show of support for presidential hopeful Boris Nadezhdin’s bid to challenge Putin in an election this month, on top of the hundreds of mourners who ventured to express public support for Navalny in Tbilisi demonstrate that Russian emigres are continuing to seek ways to bring about change back home.

It is now up to the opposition leaders in exile to direct their energy.

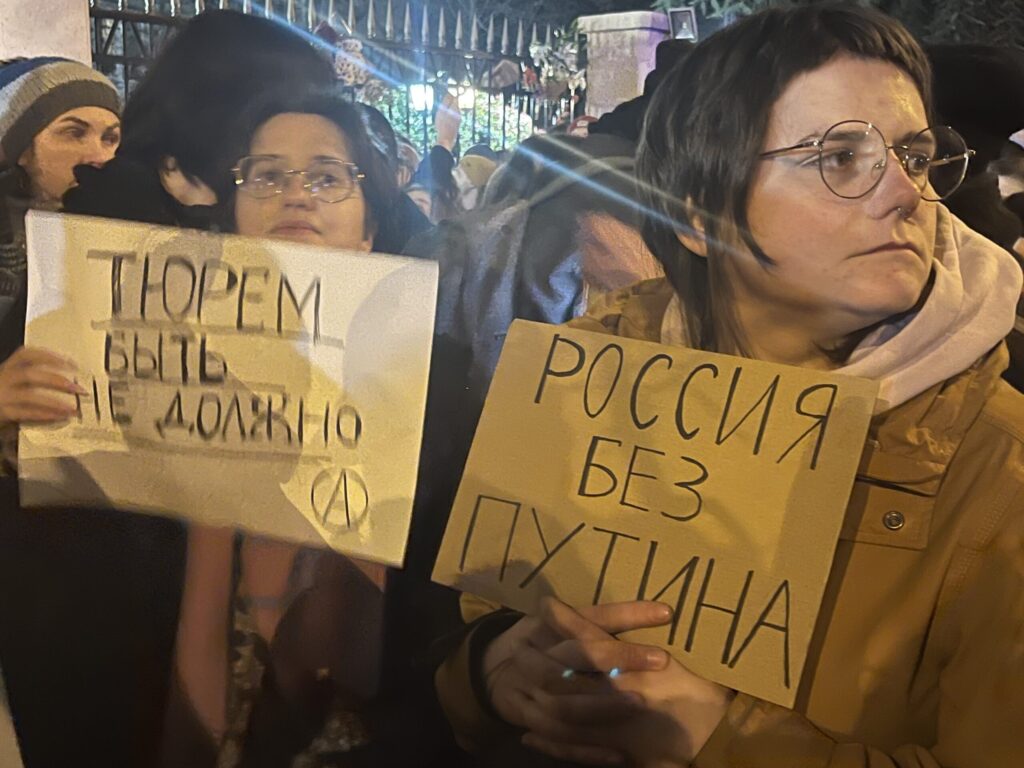

But as the rally in Tbilisi began, it seemed the protesters were reverting to the ineffectual past, meekly shouting the familiar chants “Russia without Putin!” and “Down with the Chekist government!” that had echoed at protests in Russia for well over a decade. A solitary light shone from one of the embassy’s windows, and some joked about how a beleaguered Swiss diplomat had to work overtime this particular night.

Just a few weeks earlier, many of the same emigres had waited in long queues to put down their signatures in support of presidential candidate Nadezhdin, an antiwar former liberal lawmaker who had hoped to be allowed to run against Putin in the March 15-17 election. Although his disqualification—which came on February 8—had already felt inevitable, many I spoke to said they viewed their act as an important symbolic gesture.

This rally for Navalny, in front of a building that certainly held no menacing Russian officials, somehow felt even less than symbolic, however.

The Kremlin’s seemingly invincible authoritarian machine strips Russian citizens—both at home and in emigration—of the ability to have any tangible impact on their country’s public affairs. Inside Russia, politics have been replaced with repression, while abroad all political actions have been relegated to the symbolic, or not even.

That’s why Alexei Navalny’s death has been so strongly felt, if not necessarily visibly.

‘I am not afraid’

Navalny was one of the few anti-Putin activists who managed to achieve tangible results in recent years—from galvanizing apolitical young Russians to protest, to opening campaign offices across the country and recruiting thousands of volunteers, to developing election strategies that in many cases succeeded in eroding the ruling United Russia Party’s stranglehold on political power despite Russia’s noncompetitive elections.

He may have hoped his defiant homecoming in the face of certain arrest, following months of treatment in Germany from poisoning—almost certainly carried out by Russian security officers acting at the Kremlin’s behest—would rouse his supporters to action. “I am not afraid and you shouldn’t be either” became his rallying cry. But his decision to return in January 2021 actually diminished his ability to make a difference.

The Kremlin arrested him as soon as he set foot in the country and never let him go. Moreover, it launched another immediate, brutal crackdown on civil society, declaring Navalny and his organizations to be “extremist,” a designation that threatened long prison sentences for all his activists. Most fled the country.

Navalny’s impact

The crowd at the Tbilisi protest continued to swell, with demonstrators numbering in the hundreds within hours of the news of Navalny’s death. Despite the potential risks back home—the protesters must have known they were being photographed—the numbers underscored that Russian emigres were not taking it lightly.

The chants grew more strident as anger permeated the demonstration. Signs reading “Putin is a Killer!” appeared and demonstrators shouted “Putin, zdokhni!” which roughly translates as “Putin, croak!” Cries for vengeance in the form of the expression Navalny himself popularized—“We won’t forget, we won’t forgive!”—were also heard.

Flowers and candles reflected the profound sense of sorrow. This time, Navalny wasn’t just assaulted or imprisoned. He was gone.

“Politics is a dirty business” was a mantra of many young Russian emigres from Moscow and St. Petersburg prior to their exposure to Navalny’s anticorruption investigations.

When they were completing high school and applying to universities, Russia’s economy grew to record heights. Masha, a 24-year-old graphic designer from Moscow, told me that her parents—both dentists—were happy that what they called the financial calamities and criminal horrors of the 1990s were behind them.

“They completely shielded me from politics,” she told me at the rally in Tbilisi while holding a sign that read “Don’t give up!” For parents like Masha’s, politics were a realm of criminals and security services, not something teenagers should risk their wellbeing pursuing.

“When I saw ‘On Vam ne Dimon’ [Navalny’s 2018 investigative documentary into former President Dmitry Medvedev’s lavish corruption that has been watched on YouTube more than 46 million times], I understood there is something deeply rotten with our country’s elite,” Masha said, adding that the video prompted her to attend her first political demonstrations at the age of 18.

At the same time, many millennial emigres from large Russian cities who are now in their 30s told me they had always been aware of the corruption and authoritarianism plaguing their country but chose to ignore them because of intimidation and discouragement they felt at the end of protests in 2011 to 2013 prompted by rigged parliamentary elections followed by Putin’s controversial decision to return to the Kremlin for a third term as president.

Encouraged by economic growth and lucrative job opportunities, urban creatives steadily withdrew from politics over the next decade.

With his return to Russia in January 2021, however, Navalny brought politics back to the forefront for both demographics. On his return and arrest, Navalny’s Anticorruption Foundation (FBK) released “Putin’s Palace,” an investigative documentary implicating the president as the beneficiary of a lavish multi-billion dollar palace built on the Black Sea coast. The video has been viewed 130 million times. Thousands of mostly young Russians came back into the streets to support him.

‘A turn for the worse’

A month ago in Tbilisi, I visited a center gathering signatures supporting Nadezhdin’s presidential bid. When I asked visitors about their previous political engagements, almost all—from a 33-year-old former beauty salon owner in Siberia to a 21-year-old IT worker from Yekaterinburg near Moscow—told me they had participated in the 2021 protests to support Navalny after his arrest.

Vasily, 33, who worked in public transportion in St. Petersburg, recalled his boss lecturing him about his “political activities” after learning he had attended a protest.

“On top of that, I was detained and fined twice,” he said with a grin that revealed a set of crooked teeth. Still, he was grateful Navalny had pushed him to be “politically aware for the first time in my life.”

When the war in Ukraine started, Vasily packed his bags and fled the country, saying he could no longer morally justify earning a living from a federal budget that was also “used to commit war crimes.”

Just a few days after Navalny’s death, I asked Irina Fatyanova—an exiled Russian activist who had served as the head coordinator for FBK’s St. Petersburg office—if she thought Navalny had made a mistake returning to Russia.

“It’s a question for him—but if he believed it was the right decision, then it was the right decision,” she said.

“His return indeed triggered a mass activation,” she added, describing how FBK’s St. Petersburg office received hundreds of volunteer applications “overnight.”

“It really felt like in the 2021 [legislative] elections, United Russia was going to lose on all fronts,” she said of the effects of Navalny’s “smart voting” campaign that sought to unseat members of the ruling party by focusing the protest vote on candidates with the best chances of beating them.

“That was the case on paper but not in practice Fatyanova said. “Unfortunately, things took a turn for the worse in a way none of us could have predicted.”

Grieving for a ‘lost relative’

Less than 48 hours after the state penitentiary system reported Navalny’s death, dozens of emigres crowded an underground Russian-owned venue in Tbilisi for the scheduled concert of СБПЧ (SBP4), a popular contemporary indie band from St. Petersburg now living in exile in Berlin.

“We contemplated canceling the concert,” the band’s charismatic front man and popular cultural figure named Kirill Ivanov told the crowd. “But then we came to the conclusion that Alexei would not want us to suddenly stop what we’re doing on his behalf, and that, in such difficult times, it’s important for us to be together, to feel each other’s elbows at our sides.”

Over the next two hours, SBP4’s lively, naive tunes offered catharsis and temporary escape from the continuing horrors perpetrated by the regime everyone in the room had fled. Part-way through, Ivanov paused to address the audience on another pressing issue.

“We are soon entering the third year of the war in Ukraine, and Ukrainians continue to suffer the most—and we must do everything in our power to continue to help them,” he said. “But in all this, we must remember to not lose or forget about ourselves and to recognize how difficult it is—mentally, physically—to leave our country so suddenly.”

Many attendees I spoke with found the music a poignant reminder of the home they yearned for. But Navalny’s sudden death—had clearly taken a psychological toll.

“It wasn’t just the death of my former employer or just another political prisoner—it felt like I had lost a close relative,” said Fatyanova, who despite never having met Navalny echoed a sentiment I heard from many other emigres. “His plainspokenness and ability to instruct and teach without didacticism made him sympathetic to thousands of people.”

Navalny would often send personal messages to low-ranking volunteers commending their work, she said.

Even during his time as a prisoner, he continued to communicate with the Russian people, offering thoughtful reflections about ongoing events. They were posted on his social media channels by his campaign associates. He also exchanged letters with exiled dissidents and wrote messages of support to ordinary Russians facing political persecution. In video recordings of his court appearances, he can be seen advocating common sense and the rule of law to his captors, often with a smile, asserting his constitutional rights as a Russian citizen, of which the state had stripped him.

The mourners’ raw emotions weren’t prompted solely by the fact of his death but also the incredibly harsh way it had occurred—in an isolated Arctic prison colony at the outer reaches of the civilized world—which evoked a particularly harrowing sense of horror. It served as another stark reminder for emigres that, as Navalny’s widow Yulia Navalnaya would assert in front of the European Parliament 12 days later, their country is governed by a “criminal gang.”

“With the death of Boris Nemtsov [another opposition leader who was shot in the center of Moscow in 2015], the regime showed it can kill someone with a snap of fingers,” Ilya, a 30-year-old musician from Moscow told me outside the SPB4 concert. “With Navalny, they demonstrated how they can do it through a long, drawn out and painful process—poisoning, imprisonment and torture by hunger.”

Many of the emigres I spoke with mentioned loss of sleep, prescription refills for anti-depressants and overconsumption of alcohol.

“I had a stone-cold reaction,” Fatyanova told me. “I couldn’t cry for an entire week probably because I was in denial or maybe because I was constantly surrounded by friends.”

How to stop Putin?

Not all emigres I met gave in to desperation, however, partly thanks to statements by Navalny’s widow Yulia— immediately following the news of her husband’s death.

She addressed the Munich Security Conference in a scheduled speech on the day the news broke, promising—with a stoic expression and red-rimmed eyes—to avenge her husband’s death.

Two days later, she produced another announcement on FBK’s YouTube channel addressing a Russian audience with a message that she would double down on Navalny’s work.

“I got a vague feeling that something revolutionary might be on the horizon—because Yulia said she would continue his work, but didn’t specify how, which leaves room for speculation,” Pyotr, a 27-year-old artist from St. Petersburg, told me.

While many interpreted Navalnaya’s message as encouragement to anti-regime Russians, some pro-Ukrainian observers criticized her for failing to mention Ukraine.

Fatyanova rebutted the accusation, saying Navalnaya’s job is not to be the “ideal politician for Ukraine,” but rather acknowledge the masses of grieving anti-war Russians.

“Her husband had just died and I’m sure it was difficult to find the right words that would appeal to everyone across the board,” Fatyanova said. “Alexei was an unwavering figure, and as someone who is inheriting part of his political capital, she also needs to show steadfast leadership qualities.”

Debates about how emigres can have a tangible impact against Putin’s regime continue.

A few days after Navalny’s death, three independent Russian media platforms—Help Desk Media, Meduza and Dozhd TV—launched a joint initiative that would enable Russians to anonymously and safely subscribe to a platform that would let them contribute monthly donations to help Ukrainian civilians. For many Russians abroad, assisting Ukraine’s defense against Russian aggression appears the best instrument to oppose Putin.

Fatyanova donates to Ukraine’s armed forces.. “But I also understand why many would refuse to do so,” she said.

In Russia, such donations could result in treason charges and 20 or more years in prison.

Still, she says, other forms of aid, such as helping Ukrainian civilians evacuate from war zones, is also important, as it can assist the Ukrainian army to fight more effectively, not having to worry about collateral damage.

For now, many Russian emigres are taking solace in images showing thousands of their compatriots in Moscow flocking to Navalny’s funeral and visiting his grave, risking persecution.

They defy the notion that Russian society has become entirely politically paralyzed and serve as a reminder that, despite billboards brandishing the Kremlin’s pro-war “Z” symbol or advertising Putin’s reelection campaign, there are still allies back home.

Top photo: Russian emigres in Tbilisi mourn Navalny