TBILISI — Slender and mild-mannered, Daria Apakhonchich—a 38-year-old Russian-language tutor and activist who fled her country in 2021—told the story of how she became the first artist and teacher to receive a “foreign agent” label back home to a crowd of inquisitive Georgians.

“Everything was there, in front of our eyes—all of the repressions, all the [draconian] laws, but still, the entire time, we held out hope… hope that maybe things wouldn’t get so bad, or maybe we would find ways to adapt,” she said, her gesticulations emphasizing the sense of tragedy that Russian civil society failed to stymie authoritarianism.

Apakhonchich was speaking as a guest at an event that would have been unimaginable in the city—with its strong anti-Russian sentiment—just a few months ago. A popular independent Georgian documentary center was screening a Russian film called “Of the Caravan of Dogs,” about how censorship descended on independent media and civil society as part of a series titled “What Happened in Russia.”

The films were shown against the backdrop of Georgia’s implementation of its own “foreign agents” law. Critics liken it to the measure the Russian government enacted in 2012 that facilitated the Kremlin’s mounting crackdown on domestic dissent. According to the organizers of the event, the ongoing screenings serve as an attempt to understand the consequences Georgians may face through the perspective of Russia’s experience.

Two weeks earlier, amid tear gas billowing at a protest against the legislation outside Georgia’s parliament, 20-year-old Mark Lissitsky—a queer-identifying Russian emigre with Ukrainian roots—was crouched on the pavement handing saline solution to the Georgian protesters huddled around him.

On discovering that he was from Russia, one of the protestors gave him a thumbs up before yelling, “Thank you for standing with us!”

Those incidents illustrate how Russian emigres are becoming active participants in Georgia’s battle for democracy either by their own volition or invitation to speak about their experiences.

That is a new development. For much of the last two years, the Georgian public—especially in younger, more liberal circles—has been dismissive of the wave of new arrivals from their country’s northern neighbor since the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Still, not all emigres choose to take part in demonstrations, whether from fear of being barred from re-entering their country, discomfort with chants of “Russian slaves!” directed at the Georgian police or simply feeling it’s not their place.

From Euromaidan to the Georgian parliament

With a social circle primarily composed of Georgians, Lissitsky, who asked to be called by a pseudonym, is an anomaly for most Russian emigres here.

That is partly because his mother, a Jewish woman with Odessan roots, traveled to Georgia after the 2008 Russo-Georgian war, a 16-day conflict that resulted in Georgia’s losing its Russian-backed breakaway regions Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

She came as a volunteer to help the country recover from the conflict’s fallout. Fourteen years later, the friends she made in Tbilisi repaid the favor by offering to house her 18-year-old son as he fled a country gripped by militarism and repression.

In his hometown in Russia’s Ural Mountains near the city of Yekaterinburg—a place Lissitsky describes as “distant from politics”—his Ukrainian father and Jewish mother had fostered an open environment by not sheltering their son from Russia’s dark realities.

By age 12, Lissitsky was already reading work by the independent journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot to death outside her Moscow apartment in 2006 in what many suspect was a politically motivated assassination.

Now a daily participant in Georgia’s protests against the foreign agents law, Lissitsky had attended his first demonstration as a child with his mother during a visit to Kyiv in 2014. At the time, Ukraine’s “Euromaidan” demonstrations led to the ousting of the Russian-backed President Viktor Yanukovych, and many observers now compare it to the Georgian public’s current fight against a government suspected to be Kremlin-backed.

Being a young gay man in Russia contributed to Lissitsky’s politicization, he said. “When I watched documentaries about how [the Chechen leader] Ramzan Kadyrov violently persecuted gay men, I knew I had no future in Russia,” he told me.

From age 14 to 19, Lissitsky courted a classmate whom he asked me to call Alex. In a country where public displays of same-sex affection are now punishable with prison, they kept their relationship secret. Even now, their parents believe they were just “the closest of friends,” he said.

It was politics—clashing opinions over Russia’s war in Ukraine—that severed their relationship. On learning about the Bucha massacre—the mass murder of hundreds of Ukrainian civilians by the Russian army in April 2022, Lissitsky told his then-partner the news.

“Well, they deserved it,” Alex responded.

Lissitsky says he struggles to this day to understand why Alex fell victim to Russian state propaganda. “Perhaps it was our closed environment in a remote village,” he speculated, describing how he would bombard his circle of friends with news of Russian atrocities in Ukraine. The feeling of “not being heard” eventually motivated his departure from the country.

Two months after Lissitsky left for Georgia, Alex was drafted into the Russian army during a biannual military call-up period. Lissitsky pleaded with him to avoid conscription, offering family connections he used to bypass his own draft, or money to pay a bribe. But Alex refused, telling Lissitsky he wanted to avoid problems in the future.

As with many young conscripts in good physical condition, Alex was coerced by his superiors into signing a military contract with lucrative payouts and was soon sent to the front lines with little training.

“I continued to plead with him to surrender or find some other way out,” Lissitsky said of their back-and-forth conversations through the Telegram messaging app. “But he refused, saying it was his duty to defend the Motherland.”

“And what motherland is that?” Lissitsky described telling Alex. “Your motherland is here, in the Ural Mountains, not out there in Ukraine!”

After some time, Lissitsky said it was clear from his messages that Alex had begun to realize the futility of his time in Ukraine.

But it was too late.

In January 2023, Lissitsky received a message from Alex’s mother. “Alex is no longer with us,” it read. He was survived by his single mother and younger sister. “They haven’t even paid them the 3 million roubles ($33,000) that were promised for his service,” Lissitsky said, sighing.

Perhaps still too young to process the trauma, Lissitsky showed little emotion. But I noticed his hands shaking.

A few months after Alex’s death, he met a new partner through the Tinder dating app, a 26-year-old Georgian law student. Lissitsky now has a large group of Georgian friends who are willing to accommodate his lack of Georgian by speaking Russian.

Together, they attend the protests, which Lissitsky feels are vital to the Georgian public’s ongoing hopes for their country to join the European Union. Nearly 80 percent of the country’s population support EU integration, according to recent polls. Dashing those hopes would put the government at odds with most of the population.

“I am a Russian citizen, and this law was taken from my government’s [playbook], and it could halt Georgia’s European ambitions,” he said referring to the numerous warnings both US and European officials have given the ruling Georgian Dream Party.

“When Georgia reaches its European goals, I want to reflect on how I was part of that history,” he said.

But not all Russian emigres feel as welcome at the protests. Danya, a 24-year-old poet from Moscow with some Georgian roots, attended a few times with his Georgian cousin. “Everything would be great for 15 minutes, we’d be chatty and friendly,” he told me at one of the protests, producing a wry smile on hearing accusations of “Rusebo,” Georgian for “Russian slave,” hurled at Georgian Dream deputies.

Then Danya’s cousin “would suddenly tell me she would now be ‘joining her friends’—making it clear I was not welcome in her [Georgian] social circle in such a context,” he said.

Stories from a foreign agent

One point I often hear repeated by young, politically engaged Georgians is that they differ from their Russian peers in their unwillingness to accommodate any government actions that resemble authoritarianism.

In one of Tbilisi’s most popular movie theaters, Amirani Cinema, a Georgian audience member echoed the sentiment during a Q&A following the “Of the Caravan of Dogs” screening.

“I am not like you in that I have no hope that things will still be okay after the [foreign agents] law is passed,” a young Georgian woman told Daria Apakhonchich. She followed with an uncharacteristic admission: “Still, you are a hero.”

It’s likely that the liberal Georgian public’s prior disregard for Russian emigres has contributed to a lack of understanding, something reaffirmed by comments from another audience member.

“For two years now, we’ve had many Russians come here, and we don’t know their politics,” a young Georgian man said into the microphone. “After seeing this film, I can’t begin to imagine what it’s like to have Russian citizenship,” he added. “We must show complete support for Ukrainians, but now I feel we must also express our support for Russians like you who left their country because they want to live in a free society.”

Still, such sympathy is not entirely widespread. Just moments after leaving the screening, I noticed Georgian acquaintances sharing on social media a map of Tbilisi highlighting Russian-owned establishments and calling for a boycott.

One Georgian friend, Gio, a 27-year-old graphic designer, described to me how he took a friend who is “very anti-Russian” to one such venue to show her that the Russians working there are “people too.” They had a “wonderful” time and even befriended another group of Georgians singing traditional songs at the next table—only to realize they were some of the same Georgian Dream deputies they had been protesting for weeks.

“It was very surreal,” Gio told me.

When I spoke to Apakhonchich after the screening, she told me she had been moved by the reception she received, a departure from the typical dismissal she received from Georgian civil society activists.

Despite having lived in Georgia since 2021—longer than the tens of thousands of emigres who arrived here after the invasion of Ukraine—the only Georgian friends she’s managed to make were her local grocery store clerks and fellow yoga class participants, she told me. “Simple, ordinary people.”

But when attempting to engage with local civil society by proposing joint events or collaborative projects such as the presentation of a book featuring illustrations by Ukrainian children, she was often ignored. “It was strange,” she said. “In theory, these are the people with whom I should have the most common ground.” She attributes such attitudes to Georgians’ fears about the optics of hosting Russians amid strong anti-Russian sentiment.

In some circles, that approach seems to be changing. In addition to the invitation to speak at the screening, independent Georgian media outlets now often reach out to Apakhonchich for comment. “It’s too bad it has come at such a tragic time,” she said.

As the first artist to be granted the foreign agent status in Russia, Apakhonchich is unique, which is why she believes so many Georgian organizations are now reaching out to her.

She discovered her name on the foreign agents list in Russia in 2020 at the end of a five-year period during which she published feminist literature and coordinated an anti-war camp for Ukrainian and Russian activists in Finland.

The designation meant that she would be required to file a report to the authorities detailing all her finances four times a year. “They could even flag me for a shared restaurant check with a European guest in St. Petersburg,” she had explained to the audience after the screening.

One scene in the film “Of the Caravan of Dogs” features a television clip of Russian President Vladimir Putin with a scowl on his face issuing a grim warning to Kremlin opponents, whom he refers to as “scum and traitors, and we will spit them out of our mouths like flies.” Georgian audience members sitting beside me gasped.

The visceral reaction was prompted by the recognition of Putin’s rhetoric in their own politicians’ speeches, as audience members described during the Q&A. Georgian Dream members have recently begun demonizing the protestors and members of the opposition as “traitors.”

Last month, the party held a pro-government rally in Tbilisi mostly peopled by villagers who had been marshaled into the city on buses. Observers noted that most participants were low-wage workers who agreed to take part in the rally because they feared losing their jobs.

Speaking during his first public appearance in years, the party’s founder, oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvilli, accused the opposition of acting at the behest of a Western “global party of war.”

Starkly new to Georgians but familiar to Russians, the rhetoric has put the emigre community on high alert. Georgia is home to the largest single exile group of Russian political activists, of whom the Georgian government has been relatively tolerant until now, with only a few notable cases of activists and journalists turned away at the border.

Apakhnochich, who is waiting for German humanitarian visas for herself and her children, fears such incidents could become more common under the political status quo. “I feel like I’m reliving this trauma from the perspective of a witness,” she told me.

Moreover, Russian emigres have registered several new NGOs in Georgia, which could be put in peril under the foreign agent law.

Choose to Help

On the corner of a narrow alley in Tbilisi’s tony Vera neighborhood, a sign that reads “Choose to Help,” adorned in Ukraine’s yellow and blue national colors, sparkles over a doorway. Inside, a medley of donated clothes from men’s down jackets to baby socks hangs in showroom style waiting to be claimed by Ukrainian refugee families.

Ukrainian children sometimes gather in the space to receive free English-language lessons from European expat volunteers.

Choose to Help—registered as an NGO in Georgia last fall—is one of several organizations opened by Russian emigres in the city whose founders are now scrambling to draw up contingency plans.

The foreign agents law’s main targets are purportedly domestic NGOs like the anti-corruption organization Transparency Georgia as well as independent media outlets. Choose to Help poses the government no apparent challenge.

But the fact that it receives virtually all its funding from foreign donors—Russians eager to assuage guilt over their country’s aggression against Ukraine—could put it directly in the authorities’ crosshairs.

Its closure would be an “immeasurable loss” for the community of Ukrainian refugees in Tbilisi, said one of Choose to Help’s coordinators, a woman in her 30s from St. Petersburg who asked to be called Anna.

“The [Ukrainians] who come to our organization are typically from working class families from the eastern part of the country, who come to Georgia by way of Russia and lack the means to travel to Europe,” she said.

Choose to Help’s volunteers are unpaid, and the organization is already struggling to source enough donations to stay afloat. “We literally contradict the stereotype that the Georgian government tries to paint of ‘rich NGOs living on European grant money’,” Anna said with a nervous chuckle.

Even if the law does not lead to an immediate shutdown, any additional constraints placed on the organization’s bookkeeping could effectively close it. The accountant is already overwhelmed, Anna explained.

Still, she holds out hope that an energized Georgian public will win its fight against the law. “The sheer numbers are just so impressive,” she said.

A life in Georgia

Backing down is not an option for Lissitsky, who intends to plant roots in Georgia. He will continue to attend the anti-government protests, he said, goggles on his face and a medic pack in hand, until the status quo changes. Georgia, he added, is now “home,” and he is not considering moving elsewhere.

But another piece of largely overshadowed legislation parliament plans to consider could hinder his future with his Georgian partner. In a move many perceive as a method of galvanizing its conservative base, Georgian Dream announced in March its intention to pass an “anti-LGBT” law that would prohibit same-sex couples from adopting children and ban “gatherings aimed at popularizing same-sex family or intimate relationships.”

When Lissitsky first arrived in Tbilisi, he noticed rainbow flags painted on walls in the hillside neighborhood of Mtatsminda. “Finally, I thought to myself, I’ve come to a place where I’m not demonized,” he told me. When I asked if he plans to build a life with his partner, he said, “Of course, maybe even adopt a child sometime down the line.”

That may soon prove difficult, if not impossible.

Lissitsky’s partner first came out to his parents a few months into their relationship. He asked them to prepare a dinner table for a “close friend.” Before they sat down to eat, he made the admission to his family.

“It was an hour of tears and arguments,” Lissitsky recalled with a smile on his face. “But eventually, we all sat down and his parents told him that if he’s happy, they’re happy.”

Lissitsky now practices Georgian with his partner’s father while helping him renovate their summer home in the countryside. His own parents, who have finally saved enough money to leave Russia, plan to soon move to the seaside Georgian town of Batumi.

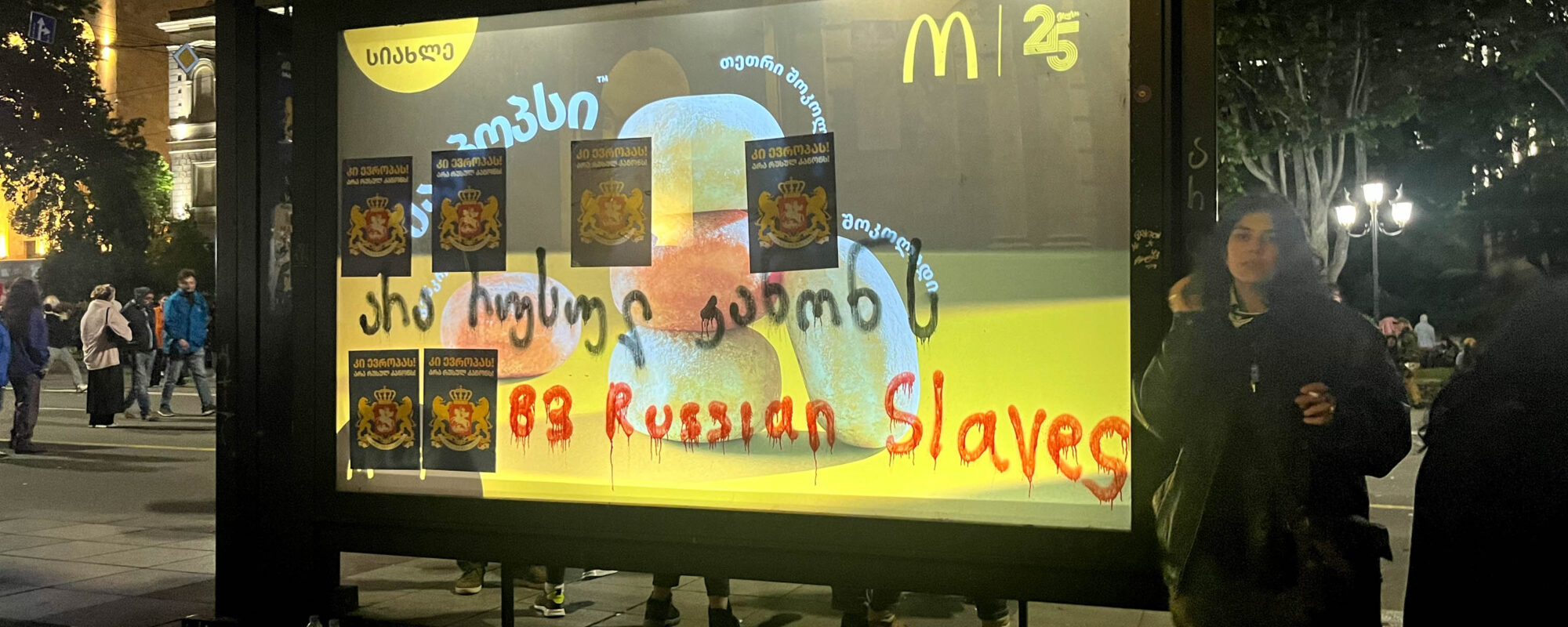

Top photo: Graffiti on a bus stop in front of parliament referring to Georgian Dream deputies