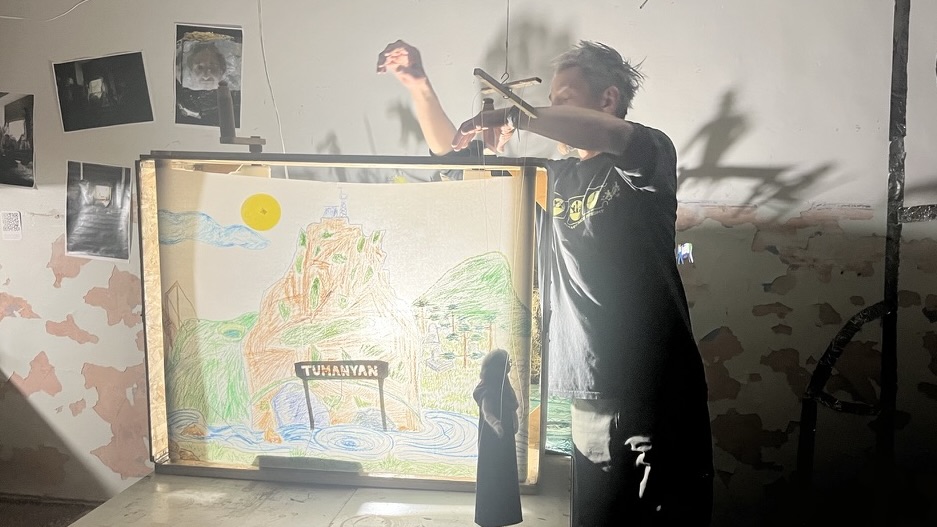

DILIJAN, Armenia — A group of cosmonauts is forced to land its spaceship on the planet Dzaghidzo—coincidentally the former name of the Armenian village Tumanyan—when it runs out of fuel. The vessel, the legend goes, is fueled by tales. The travelers eventually come across an elderly Armenian woman who knows every little about Dzaghidzo’s local inhabitants.

For weeks, this local Scheherazade tells her tales, eventually providing enough to propel the cosmonauts back on their journey.

That is the premise of a puppet show a group of recently exiled Russian artists staged for locals in northern Tumanyan, roughly 100 miles north of the capital Yerevan. The play was intended to symbolize the relationship between the performers and their new neighbors.

Shortly after Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, an abandoned textile factory was transformed into Abastan, a colony for artists who fled the militaristic and increasingly authoritarian regime of Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Most locals are confused about what these Russians are doing there. Nevertheless, they welcome the newcomers with open arms. Some parents even allow their children to wander up to the old factory to learn from the artists. It helps that all the locals, young and old, still speak Russian.

Although relations are sometimes fraught in other former Soviet countries, the phenomenon of peaceful coexistence between post-invasion Russian émigrés and their Armenian hosts is not unique to Tumanyan.

In Dilijan, a more developed town roughly an hour’s drive from Abastan, recently settled Russians—primarily young tech workers with children—have also integrated successfully, introducing recycling initiatives and vaccinating the town’s stray dogs.

That phenomenon is also not new.

Along the highway connecting Dilijan to Tumanyan, an old Russian woman in a headscarf sells vegetables at a stand to Armenian passersby. Behind her stands Fioletovo, one of two remaining villages in the country that has been inhabited by Molokans, a Russian sectarian community that has lived on these lands, since the 19th century.

Like many of the more recently arrived Russians, the Molokans were also pushed into exile by the policies of an authoritarian leader. Tsar Nicholas I banished the sectarians for their refusal to serve in the imperial army as well as their conflicts with the state-supported Russian Orthodox Church. Even throughout its time as a secular Soviet republic—when the USSR was notorious for persecuting religious groups—Armenia allowed this community to exist largely untouched.

The welcoming climate in rural Armenia has enabled new Russian exiles to recalibrate their lives and even leave a tangible impact on their host country. In contrast to neighboring Georgia, which has a strained history with Russia partly due to the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, the willingness of Armenians to engage with Russians, coupled with the country’s policy of allowing Russians to enter the country without a passport, has eased the process of integration.

At the same time, Russia is home to the world’s largest Armenian diaspora—over 1 million people—further strengthening ties between the two peoples.

But while Armenia’s rustic charm, distance from the war in Ukraine and ever-growing repressions at home may lull Russian émigrés into a depoliticized state, the country’s own unresolved conflict with neighboring Azerbaijan has dragged Russians into an entirely different context of war.

Decades of violent post-Soviet territorial clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan erupted in 2020 and 2023 with the deaths of thousands of servicemen and the displacement of over 100,000 ethnic Armenians into Armenia, further exacerbating soaring housing crisis initially triggered by the arrival of Russians.

Even some Molokans, whose creed forbids them from taking up arms, were forced to the front lines of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war.

‘Evil persists’

Trudging down Fioletovo’s bumpy dirt road, which runs between two rows of wooden houses adorned with ornate window carvings, you could be excused for thinking you are walking through a village in central Russia. Withered cabbages and carrots hang on signposts in front of some homes, indicating vegetables for sale. All the street signs are in Cyrillic script.

But the snowy mountain range that soars above the village immediately situates visitors in the South Caucasus.

Fioletovo was founded in 1842 by Molokans, who in many ways resemble Western Christian denominations such as the Quakers who believe in seeking divine guidance directly from the Bible. Churches, priests and other elements of institutionalized religion are seen as more likely to corrupt God’s word than convey it.

“Our ancestors chose this location because there was an imperial army outpost nearby,” said Tolik, one of the Fioletovo residents who agreed to speak with me and my travel companion Yakov Lurie, a Russian social anthropologist who fled St. Petersburg after Russia invaded Ukraine. With the help of European grants, Tolik recently opened a Molokan Heritage Museum in the village. Back then, the outpost protected Molokans, resolute pacifists, from roaming bandits.

“We try to live as Christ lived: equality, brotherhood and love,” he explained. “But humanity is such a creature… that evil persists.” With his long bushy beard and warm, beady eyes, he spoke a Russian dialect that was simultaneously clear to modern ears and dated in its simplicity.

“There just can’t be a place like this, people like this,” wrote the Russian writer Pyotr Vail of the Molokan community. Vail, who emigrated to the United States from Soviet Latvia in the 1970s and whose mother was born into a Molokan community, visited Fioletovo in 2007 for an article of his own.

“In the 21st century, it is unthinkable that such immersion into the beginning of the 19th century could exist. A camera isn’t just forbidden here, it’s anachronistic,” he wrote for Geo Magazine.

The name derives from the Russian word for milk, moloko, referring to the tradition of drinking milk during Lent. The practice stems from the interpretation of a passage from the First Epistle of Peter, “Like newborn infants, desire the pure milk of the Word.”

A typical Molokan village has an elder who is chosen to serve for life. During weekly congregations, he leads the prayers and baptizes children. The congregation sings psalms and recites prayers. They also gather for weddings and matchmaking ceremonies.

Separately, a village council elected through a democratic voting system looks after the well-being of the locals. Children attend Russian-language schools, where teachers use standardized Russian textbooks.

When Vail asked locals if the Russian government did anything for their community, they responded that “Russia is not a cash cow.” A Russian parliament deputy who visited the village in the late 1990s, he writes, responded to requests for donations with: “They’re your children, you pay for them.”

“Such a response feels odd against the backdrop of [Moscow’s] declared concerns about compatriots abroad,” Vail quips.

While they appear to be relics of a bygone era, the Molokans have been slowly edging toward modernity over the last two decades. During his visit to Fioletovo, Vail noted that a modern public bath, heating, electricity and a medical center had been installed with funding from an American NGO.

These days, many younger Molokans use smartphones with internet access. “You can’t do anything without the internet these days,” Tolik told us, smiling.

They also continue securing financial aid from foreign institutions. Tolik opened his museum with the help of a German tourism nonprofit. “It’s funny,” he mused. “We’re being helped by a European institution at a time when Europe is Russia’s main enemy.”

A defining feature of the Molokans that probably contributes to their long-held status as Armenia’s hardest-working community is that they do not consume alcohol or tobacco. Vail commented on the aberration: “Where else can you find such a compact community of Russian people who for 300 years have remained sober?”

Scholars speculate that the Molokans sustained their work ethic through forced adaptation to a new and inhospitable climate. “The fertile black soils of central Russia” were swapped for “more challenging mountain environments in the Caucasus,” the American academic Susan Hardwick writes in her essay “Religion and Migration: The Molokan Experience.” Nevertheless, she adds, the Molokans “were able to establish self-sustaining agricultural operations… and mechanization of all kinds was used on [their] farms by the 1890s.”

Although the local Armenian populace was initially suspicious of the newcomers, contact was gradually established “on the basis of economic and trade relations,” writes academic Ivan Semyonov in his History of the Transcaucasian Molokans and Dukhobors.

“The local population had a lot to learn from the newcomers, since the Russians brought more advanced tools, new and better breeds of livestock and more advanced farming methods, which contributed to the development of vegetable gardening in the region,” he says. The Molokans, in turn, learned from indigenous residents how to adapt their materials to the local lands and to raise sheep.

Now Molokan men work primarily in carpentry and construction and are known as some of Armenia’s most skillful builders. In Dilijan, they can also occasionally be spotted selling their cabbage and milk to the locals.

According to Tolik, the Molokans of Fioletovo are not just aware of the newly arrived Russians but try to engage with them regularly, inviting them to make traditional Russian dumplings and go mushroom hunting. The Molokans call the post-invasion emigres nashi, “our people.”

Irina, a 39-year-old marketing specialist who moved with her husband and son to Dilijan shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, joined the mushroom hikes but has mixed feelings about Molokan practices. “People keep romanticizing them as some sort of sacred community, preserved from a bygone era,” she told me. “But at the end of the day, they’re very conservative and patriarchal, and many still prevent their children from getting a higher education, which is not really my cup of tea.”

Networking in the playground

Tucked away between densely forested mountains, Dilijan—a spa town of about 18,000 that was formerly a resort for Soviet artists and composers—now hosts roughly 1,000 Russian émigrés. From the town square, where a memorial to the iconic 1977 Soviet film comedy Mimino—which celebrates the friendship of a Russian, Georgian and an Armenian native of Dilijan—welcomes visitors with warmth and whimsy, the main road snakes up into the hills where every tenth wooden home is now inhabited by Russians.

One afternoon in March 2023, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan was dining with his wife at a new, upscale restaurant in town when he noticed a group of Russians picking up trash on the street outside. According to a waitress, he immediately asked his security guards to bring him latex gloves from the shop across the street.

Slipping them on, he ran outside to join the Russians for their subbotnik—a Soviet-era tradition in which people take part in community-service activities on a Saturday, from which the word is derived. Shortly after, the prime minister’s wife, Anna Hakobyan, shared a photograph of her husband working with the émigrés on her Facebook page, with a caption in Russian: “Don’t think it’s just [Russian] relokanty [picking up trash]. Locals have joined the effort too!”

The term relokant, which loosely translates to “relocated person,” is a common self-identifier used by many Russians who fled their country in 2022. Terms like “exile” may have too heavy a political connotation, implying an inability to return.

Many Dilijan locals to whom I spoke, both Armenians and Russians, said the newly arrived relokanty have injected the town with a new, urban middle-class culture. In addition to introducing recycling and vaccinating most of the town’s stray dogs, they have opened yoga and Pilates studios.

While it’s unclear how Pilates studios could benefit the predominantly working-class locals who can’t afford them, residents told me they welcome such “improvements.” Ivanes, a 30-year-old bartender, was happy they’ve made his hometown “more attractive” and that the businesses they open provide work for locals.

Artemy, an Armenian cab driver who zooms between Tbilisi, Dilijan and Yerevan almost daily, says business has been booming. Ninety percent of his customers are Russian relokanty. He said he had lived in Russia half of his life, when he would experience racism from Russians “weekly.”

“But I know that [the Russians here] are different, otherwise they wouldn’t be here,” he told me. “They often tell me, ‘Artemy, we’re so sorry for all the horrible experiences you had in our country. Thank you for welcoming us here.’”

For recent émigrés like Irina and her programmer husband, who represent the majority of Russians in Dilijan, the town may feel a bit like an American suburb. Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, is just an hour and a half away. Dilijan boasts two well-reputed private schools, and the large homes available for rent or purchase are well-suited for remote work.

“The playground has been our main networking space,” Irina said, chuckling over a Zoom call while on holiday in Moscow. In the background, I overheard her six-year-old son listing the names of his closest Dilijan friends—Russians, Armenians and children of foreign teachers.

Even before the influx of Russians, Dilijan’s economy was already on the rise, pushed by investments from the notorious Armenian oligarch Ruben Vardanyan and the Armenian diaspora. In 2014, the international educational network United World Colleges opened a Dilijan branch. Now Irina and her husband send their son there for preschool, where alongside both Russian and Armenian children, he hears lessons taught by foreign teachers in English.

The school charges $200 a month, “significantly cheaper than a private school in Moscow, and the education here is certainly better—I can tell from how our son is responding,” Irina told me. “We’ve built a community here that will enable us to stay at least a few years.”

‘Too young’ for politics

One of the driving forces behind Dilijan’s development is Impuls, an Armenian holding company that “manages assets and investments in the fields of development and territorial planning,” according to its website. Its boxy new headquarters, which look as if copy-pasted from Silicon Valley, peer over the town’s newly renovated park.

Over 50 percent of its staff is Russian, including a young woman from Russia’s Republic of Mordovia named Yulya, whose move here with her husband, Zhenya, unintentionally coincided with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Because we had already planned to move here for work, our departure was much easier than those of others who fled because of the invasion,” she told me at the wine bar they recently opened as “Zhenya’s pet project.”

Having worked in parks and recreation between the relatively small cities of Saransk and Yalta—in the occupied Ukrainian Crimea region—the move to Dilijan did not seem like much of a downshift. Asked whether they felt ethical dilemmas working in Crimea at the time, they said they were “too young” to grasp the political implications.

“Growing up in a far-flung republic like Mordovia, you feel distant from Moscow’s politics,” she told me.

Now they plan to stay until a job offer abroad comes along.

Impuls hired Yulya and her Russian colleagues for their wealth of experience in a much stronger economy.

“With colleagues who worked in Russia, it’s easier but with our colleagues who worked only in Armenia, there is a difference,” she explained. “We often need to teach them things.”

Our conversation was interrupted when an older Armenian couple entered for a drink. Downing a few glasses of wine, the man—who owns an automotive repair shop in Dilijan—began raising toasts to Russia. He placed an emphasis on the country and its people rather than its politics. He had lived in Russia for a large portion of his life and had fond memories of the notably higher salary he had earned there.

Abastan means ‘refuge’

The locals of Tumanyan have a few theories about the peculiar Russians occupying the former textile factory that looms like a fortress above their homes. One rumor has it that the Russians are part of an LGBTQ+ sex cult. The more conspiratorial townsfolk suspect they’re spies working on behalf of Armenia’s regional foe Azerbaijan.

The optimists hope the Armenian American businessman who purchased the building over a decade ago brought in the Russians to restore it. The structure was a school during Soviet times and later a textile factory that employed many of the town’s women, a symbol of local prosperity. However, Armenia’s post-Soviet embrace of capitalism left it vacant and in disrepair.

The last rumor holds some truth. Тhe new owner did lend the building to the Russians for use as an arts center in the hope they would make it habitable for the long term. But the decay was so pervasive it would take professional builders just to prevent the roof from collapsing.

A scholar of medieval Anatolia named Polina Ivanova, who earned a doctorate at Harvard and was acquainted with the businessman, came up with the idea of creating a haven for artists at political risk in their home country after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The artists chose to call their colony Abastan, “refuge” in Armenian.

The plan was also to offer short-term residencies to artists from all over the world to collaborate with Russian colleagues. The colony has hosted Russian artists since spring 2022, with occasional visits from a few Iranian artists, one Vietnamese and a few Armenians.

After Putin declared mass military mobilization in September 2022, Armenia’s proximity to Russia and Georgia—another post-invasion Russian emigre hub—transformed Abastan into a literal refuge for army deserters and others fleeing the increasingly militaristic Kremlin regime.

During the invasion’s first year, the Russian residents felt cognitive dissonance whenever hearing admiration from Tumanyan locals about Putin’s “strength.” While praise diminished after Russian peacekeeping troops stationed in the breakaway Azerbaijani region Nagorno-Karabakh failed to protect ethnic Armenians living there from an Azerbaijani offensive in September 2023, Tumanyan’s locals still welcome the Russians.

Which is not to say they always see eye-to-eye. As part of an attempt to provide some use to the village, the artists hosted a workshop for local children making crafts from repurposed materials. But when children brought home pigs crafted from plastic bottles, many parents questioned the utility of “making art out of trash.”

The artists occasionally host shows and markets in the town square, where locals pensively examine ornaments they lack funds to purchase. Davit Sahakyan, a local Armenian musician and programmer, said he was worried about the potential for disconnect between the newcomers and locals. “Residents here are quite conservative, working-class people who just focus on their own survival,” he said. “They are the last people who need modern art.”

But the head of the local community center—located in the former Soviet House of Culture building—praises the artists for their work with children. The shared language and cultural history from Soviet and tsarist eras links Tumanyan locals to the Russians, however cosmopolitan they may be. During my visit, two young Armenian drivers hired to bring Russian artists from Tbilisi to Abastan were so enchanted with the colony that they stayed overnight, sitting around a campfire and singing songs with the residents.

Whether the artists will leave an enduring impact on the Tumanyan community or whether the dilapidated state of the building will force them to move elsewhere remains to be seen.

‘Just part of everyday life’

Kirill, an activist from Moscow who is an old friend of mine and now lives in Dilijan with his partner, told me he’s skeptical about any long-term impact the émigrés might have on locals, considering the prospect of soaring rents and overall effects of gentrification of which residents may not yet be wary.

Many of the young families left Russia to protect their children, he noted. “They could have continued to live their politics-free life in Russia and earn decent salaries without uprooting their lives,” he said. “Yet they came here because they wanted to shelter their children from the militaristic propaganda infecting Russia’s schools.”

Kirill came to Dilijan shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine. His partner, also an activist and an artist, was born to a Ukrainian mother and has strong ties to that country and its language. In St. Petersburg, where she grew up, her father garnered a reputation for his provocative poetry. He died a year after the invasion. Soon after, an independent Russian media outlet accused him of a series of sexual-abuse and assault incidents.

Traumatized by revelations that unearthed unpleasant memories of her own childhood interactions with her father, his daughter now conflates her experience living in Russia with her father’s abuses. She finds it difficult interacting with Russians. In Dilijan, the couple helps Ukrainians through various remote initiatives, working far from the flocks of other Russian émigrés in Tbilisi and Yerevan.

Aleksei, a Russian journalist who writes about alcohol for lifestyle magazines, also found refuge in Dilijan’s hills. In 2021, he had published an investigative piece exposing local police in Russia’s Buryatia Republic of inflicting sexual violence against underage detainees. Following the article’s publication, the officers were arrested.

However, one was released from prison in 2022 after signing a contract to join the Wagner paramilitary group. After completing six months of military service in Ukraine, he returned to Russia and filed a criminal case accusing Aleksei of slander. The story typifies the current socio-political climate in Russia, where Aleksei is now a marked man.

Other émigrés in the town to whom I spoke, however, were reticent about discussing the war in Ukraine and their own country’s fate. On a Telegram channel called “Move to Dilijan” created by relokanty, one of the many rules pinned at the top reads: “Politics are not discussed here.”

In Tbilisi, anti-Russian graffiti and Ukrainian flags hanging from many balconies remind Russian émigrés of the context of their arrival. In Armenia, however, the absence of such vivid expression of sentiment may be playing a role easing relokanty into a state of depoliticization. “We don’t read the news these days at all,” Yulya, from Russia’s Mordovia Republic, told me at her husband’s bar in Dilijan. “Nothing becomes easier from reading it, so there’s no point.”

The fact that the war will soon enter its third year may also fuel such escapism. “We categorically understand that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a bad thing, but now, almost two full years down the line, it doesn’t feel like a pressing issue anymore,” Yulya’s husband Zhenya said. “It has somehow become just part of everyday life.”

The Molokans also try to avoid news to “keep their minds at ease,” Tolik said as he drove Lurie and me from Fioletovo to Tumanyan. “We have always been distant from politics. If the Whites come, we’ll greet them. If the Reds come, we’ll greet them too,” he explained, using Russian 1920s civil war-era terms for monarchists and Bolsheviks.

The pacifism has made it difficult for the Molokans to wrap their heads around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “It must be over resources,” Tolik mused. “Otherwise, how can a brother nation attack another brother nation?”

Even in the artists’ colony among an impressive array of paintings, light installations, found objects and puppet theaters, there was a glaring absence of politically charged work that could somehow shed light on Russia’s invasion and the country’s current political and social status quo. Nowhere on Abastan’s website is the war in Ukraine mentioned even though many of its artists left Russia because of the conflict.

Regina Abuzhenova, 29, who volunteers as a manager in Abastan, justified the omission saying that writing actively pro-Ukrainian messages could compromise the colony’s reputation in a country whose population and government does not unequivocally support either side. “Instead, we figured we would just make it an open space for any discussions in person,” she said.

Abastan resident Kiriyenkova took issue with my observations about the lack of political art saying much of the work produced during colony’s first year was heavily politicized. “At the time, it was actually difficult not to make something politicized,” she said. “But a year down the line, things have changed. I was pumping out so much anti-war art at the start, and what did it do? It didn’t make any one feel better.”

Armenia’s ‘war of its own’

Another common response I received when asking Russians about the issue was that Armenia has a war of its own over which it is counting on Moscow’s support. “Armenia has its own history, its own war, which just happened—and when you show up with your terrorist state which you are fighting against and begin to publicly condemn it in Armenia, a country still seeking [military] aid from Russia, this might appear strange and intrusive,” Kiriyenkova said.

After the Soviet collapse, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought repeatedly over Nagorno-Karabakh, which, while recognized internationally as a part of Azerbaijan, was always inhabited by a large majority of ethnic Armenians.

As a result of a cease-fire following the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Russia deployed a peacekeeping force to the exclave. That partly explains why Armenians generally viewed the Russian government favorably until September 2023. But during Azerbaijan’s most recent offensive, followed by a months-long blockade of the region, the peacekeepers largely stood by without intervening. Experts saw Russia’s inaction as a move to punish Armenia’s pro-Western Prime Minister Pashinyan after a series of spats with Putin.

Protests erupted in Yerevan following Armenia’s latest capitulation, this time with an unprecedented anti-Moscow slant.

Still, the Russians I spoke to say that hasn’t affected their lives in Armenia. While faith in the Russian government may have waned, Armenians’ appreciation for Russian émigrés has not.

“I was very worried that after this conflict, the Armenian population would direct its animosity against the Russians, but I am so proud they didn’t,” the Armenian writer Narine Agbaryan told the exiled Russian journalist Katerina Gordeeva in a recent YouTube interview. Agbaryan was echoing a sentiment I had heard from dozens of locals, pride in the ability to separate people from the actions of their governments.

Part of Armenians’ resolute acceptance of Russian migrants could be explained by the fact that they played a large role in providing aid to families who suffered from the latest Azerbaijani attack. During Azerbaijan’s September 2023 offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh, which displaced over 100,000 ethnic Armenians, Russians in Dilijan were some of the first to organize donation drives for the refugees.

In her interview with Gordeeva, Agbaryan praised the contributions of newly arrived Russians. “In Dilijan there is now a large, intelligent diaspora from Russia which mobilized to collect clothes, food and find housing for [the refugees],” she says in the interview, which shot in her hometown Dilijan.

“It was a show of humanity and unity which felt very natural, and we [the locals of Dilijan] were so warmed by these gestures as they showed us that us Armenians are not alone.”

Armenia is sandwiched between two hostile countries that have strong alliances of their own—Azerbaijan and Turkey, which still refuses to acknowledge its genocide of Armenians at the start of the 20th century. Armenia’s neighbor to the north, Georgia, lacks the resources or political will to present itself as a reliable partner. Perhaps that helps explain why the Armenian people welcome any help they get, including from immigrants fleeing the country that once colonized them.

Wine bar owners Zhenya and Yulya were among the Russians in Dilijan who participated in the initiatives to help Artsakh refugees. “We felt the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis here more because you see how it affects the locals around you,” Zhenya said. “In Russia, the war is somewhere distant. Here, it’s just 30 minutes away, which is quite frightening.”

At Abastan, residents donated all they earned from selling art to various initiatives helping refugees. “As immigrants ourselves, we collectively felt that since we’re living here, we needed to prioritize [those in need] in this country first, while Ukraine was secondary,” Abuzhenova said. “We had enough resources for Armenians, but not for Ukraine unfortunately.”

When she’s not managing the artist colony, Abuzhenova works remotely out of her rented apartment in Armenia’s second-largest city, Gyumri, where in addition to few-hundred Russians relokanty, Russian soldiers patrol the streets. Roughly 3,000 are reported to be stationed at the base there, which has existed since Soviet times.

Just a week after we spoke, a Russian conscript named Dmitry Setrakov who deserted his unit in Ukraine and fled for Armenia, was detained by Russian military police officers in the city before they swiftly sent him back to Russia. That was the first known case a Russian military deserter was arrested outside the country. His whereabouts are unknown but it is likely he is back on the front lines of Ukraine.

In her interview with Gordeeva, Agbaryan also shared an interaction she had had with an 18-year-old Russian who fled his country just after Putin’s September 2022 mobilization order. She met him when he was working as a food courier in Dilijan. The teenager called her saying he was unable to carry up her order, so she came out to greet him thinking he was lost.

After spotting him crouching on the ground, weeping, she took him into her arms to console him, she told Gordeeva. “Your mother must be relieved, she must be happy that you are here, and not out there on the front lines in Ukraine—and this is a good thing,” she recalled telling the draft-dodger.

Unavoidable realities

Faces of young men who died in the Nagorno-Karabakh wars are painted on tufa stone walls, peering down at pedestrians across Armenia’s cities. Along highways, billboards almost exclusively display military recruitment ads.

At the artist colony, I came across a photograph of a young Armenian artist-in-residence with two prosthetic legs. He is a veteran of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war now ensconced in his apartment in Yerevan writing a book about his experiences on the front lines. His friend and fellow veteran, Davit Sahakyan, played guitar for us around a campfire.

When I met Sahakyan for a follow-up conversation in Yerevan, I noticed he would wait for the green light at every crosswalk even when other pedestrians were jaywalking left and right. He, too, has a prosthetic leg.

In 2020, at the age of 19, Sahakyan was handed a conscription notice. He had never held a gun in his life and was unaware he would soon be embroiled in what would become Armenia’s bloodiest military conflict in over two decades. In August that year, a month before Azerbaijan launched its operation in Nagorno-Karabakh, Sahakyan and his regiment were deployed in what became a buffer zone on the Azerbaijani border.

“I learned how to fight only after I was in the war,” he told me in Russian with native fluency. Of his regiment of 100 men, only six survived. “We were completely surrounded and rather than fleeing toward Armenia where Azerbaijani troops were moving, we ran behind enemy lines through mountains and forests,” he said as we sat in Ilik, a popular café in the center of Yerevan where Armenian artists and poets gather.

He wore his long black hair in a ponytail, and even though his face was youthful, his eyes looked weary. “A cease-fire agreement was signed on November 10, but we got out only on December 10,” he said. “We would take food from homes in villages abandoned by Armenians,” he added. Sahakyan and his comrades eventually escaped through Azerbaijan into Iran, where they were greeted by International Red Cross volunteers.

“I saw horrors in the war. I saw my sergeant decapitated,” he said. “I would see how Azerbaijani soldiers would commit atrocities and then post videos online, and Azerbaijani social media users would cheer them on. This wasn’t war anymore; it was something animalistic.”

He said he found rations provided by the Russian government for Azerbaijani troops in abandoned Azerbaijani positions. He came to the conclusion that Moscow had been playing both sides against each other.

The Azerbaijani government has since cracked down on internal criticism of its Nagorno-Karabakh policies. “What’s happening in Azerbaijan reminds me of what’s happening in Russia,” Sahakian said. “They lay claim to a contested territory, insist on the narrative that it belongs to them and jail anyone who dares speak out against it.”

When I asked how he was coping after witnessing such brutality, he told me that he learned how to “compartmentalize.”

“No matter how much we want to believe there is, there is no real concept of humanity yet,” he said. “People are still barbarians. And when you acknowledge that, it becomes easier to process.” It was difficult to imagine how such a young, bright man—well-read, with an incredible sense of humor, who composes indie rock music in his free time—could endure such horrors.

In Russia, the fact that the army is primarily comprised of undereducated men from the country’s far-flung regions makes the war in Ukraine feel distant for residents of cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg. But in much-smaller Armenia, a country whose population is under 3 million, it was difficult to escape the 2020 draft. During my travels, I asked almost all the men I spoke with if they had served and about half said they had.

Cases like Sahakyan’s show the profound impact the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has had. Across the country, the fear that another Azerbaijani attack may be imminent is palpable. On January 13, Azerbaijan’s autocratic president, Ilham Aliyev, posted a video online in which he made dubious claims questioning Armenia’s territorial integrity, placing particular emphasis on its capital, Yerevan. His rhetoric was eerily reminiscent of statements Putin made when justifying his invasion of Ukraine.

Although his injury would exempt Sahakyan from another draft, he still recently attended a military training program “to be ready to defend myself and my loved ones.”

Sahakyan said there was one Molokan soldier in his initial regiment of 100 men despite the sect’s longstanding adherence to radical pacifism. “I don’t know what happened to him, but he could very well be dead,” he told me.

But most who were forced into the military refused to take up arms, serving as medics or cooks for their regiments instead. “We are categorically against war,” Tolik, the Molokan, told us. “‘Do not kill’ is one of our main rules. There is no justification for killing.”

Still, “no matter how much we try to shelter our people from all the conflicts around the world, some realities are just unavoidable.”

Top photo: Visitors at the Abastan residency