OUAGADOUGOU, Burkina Faso — Riding around the capital on a motorcycle—the principal means of transportation for the city’s 2.5 million residents—I was struck by public displays of patriotism and support for the government.

Every roundabout was festooned with the country’s green-red-yellow flags and those of its allied neighbors. Billboards proclaimed the army’s prowess and dedication to protecting the people. The face of the current leader, 34-year-old Captain Ibrahim Traoré—who came to power in a military coup in September 2022—graced T-shirts and public transportation.

By all appearances, support for his government appears strong.

But as I spoke with activists, survivors of jihadist attacks, militia fighters, humanitarians and local authorities from rural communities, another dimension of the country’s mood emerged. I left Ouagadougou after a 10-day visit with the impression that genuine support for the government is being steadily undermined by mounting repression and continuing setbacks on the front line of the country’s almost 7-year-old fight against jihadist insurgents.

While Western attention in the Sahel region has recently focused on Russia’s notorious Wagner mercenary group in Mali and the recent coup in Niger, the deteriorating situation in Burkina Faso has grave implications not just for the country’s 22 million citizens but also those living in the border zones of coastal countries to the south.

Since gaining independence from France in 1960, Burkina Faso has experienced a tumultuous political history replete with repression, corruption and systemic underdevelopment. From 1987 to 2014, President Blaise Compaoré ruled the country by corrupting local elites and silencing those he could not buy off. Then in 2014, massive public protests led to his removal, paving the way for the election of Roch Marc Christian Kaboré a year later. For the first time in decades, young Burkinabe (the demonym for the country’s citizens) hoped for a freer future.

Around that time, however, local jihadists who had been fighting in northern Mali returned to the country’s north and launched their own insurgency. The security services responded with arbitrary arrests, torture and extrajudicial killings. In many cases, they targeted ethnic Fulbe people, whom they perceived as being sympathetic to the insurgents.

While militants did recruit heavily among some Fulbe castes, the military’s abuses fueled insurgent numbers. Now affiliating themselves with either Al-Qaeda or the Islamic State, the militants expanded into eastern Burkina Faso. By Kaboré’s 2020 reelection, insurgents of one stripe or another controlled a fifth of the country’s territory.

In February 2022, riding frustrations over the war effort and corruption within Kaboré’s political party, Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba ousted Kaboré in a military coup. However, following a series of military defeats mid-year, soldiers in an antiterrorism special forces unit launched another coup early on the morning of September 30. That evening, the army announced on national television that it had seized power, dissolved parliament and appointed Captain Ibrahim Traoré as the country’s new leader.

‘Sovereignty discourse’

In the days following the coup, whenever Traoré left the presidential palace or barracks, he was accompanied by hundreds of (mostly) young men cheering, saluting and waving Burkinabe and Russian flags. In the second-largest city, Bobo-Dioulasso, hundreds of people took to the streets to celebrate Damiba’s departure and support Traoré. Even in Djibo, the epicenter of the insurgency in the north that at that point had been under siege for five months, there was cautious optimism.

“Damiba was worse than Roch,” a young man from Djibo told me. “Everyone celebrated when he was overthrown.”

From early on, Traoré has attempted to maintain support through what has become known as “sovereignty discourse.” This movement has been sweeping West Africa over the last two years, rooted in the rejection of colonial and neocolonial relationships, particularly with France.

Young people in the Sahel specifically are more aware than their parents of their status at the bottom of a global economic hierarchy. They understandably blame developments on decades of close relationships between their corrupt leaders and French business and political interests. Now, following a decade of failed French counterterrorism interventions, Sahelians are expressing a desire to forge their own future without interference from Paris.

The military juntas in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have therefore sought to legitimize themselves domestically by ejecting French interests from their countries. When France refused to recognize Traoré’s government, he expelled the French ambassador and called for the withdrawal of all French troops. Paris responded by stopping all nonessential humanitarian aid, refusing to issue visas to Burkinabe for cultural exchange programs, and halting Air France service to Ouagadougou.[1] Those petty reprisals and what’s perceived to be the haughty attitude of French officials have only increased the popularity of Traoré’s approach in the eyes of Sahelian populations.

While Mali’s leaders have paired their rejection of Paris with an explicit embrace of Moscow, however, Traoré has been more circumspect. Yes, Ouagadougou is dotted with Russian flags, Traoré has deepened cooperation with the Kremlin and there are indications Wagner is helping the government with its communications strategy. But Traoré has so far insisted that Burkinabe, not Russian, soldiers will liberate the country from jihadists, rejecting offers of Wagner fighters.

A few months after the military junta took power in Niger, the country joined a mutual defense pact created in September with Mali and Burkina Faso. Since then, Traoré has prioritized keeping the road to Niger open, framing the alliance as an equitable partnership to address the countries’ shared problems.

Burkinabe say elements of Traoré’s sovereignty discourse remind them of their now-beloved ex-leader Thomas Sankara. A young army captain who came to power in a coup in 1983, he’s remembered for his personal lack of corruption, defense of the country’s external interests and massive campaigns that created widespread literacy and the construction of infrastructure in rural areas. Nostalgia for Sankara, particularly his insistence that his country choose its own foreign partners, is alive and salient in Burkinabe politics.

Traoré is always seen in uniform wearing a version of Sankara’s characteristic red beret. A recent speech he gave in St. Petersburg, Russia, in which he castigated fellow African leaders for their dependence on foreign aid, harkened back to a famous address of Sankara’s at the United Nations about food security. And on the anniversary of Sankara’s assassination on October 15, Traoré held a memorial ceremony where the former leader was officially elevated to the status of “national hero.” With Sankara’s family members in attendance, Traoré laid the foundation stone for a new mausoleum and renamed Boulevard Charles de Gaulle after the former Burkinabe leader.[2]

Although Traoré has made appeals for the kind of sacrifices and service to the nation Sankara inspired, his efforts toward citizen mobilization are focused on turning the tide of the war rather than Sankara’s building of rural infrastructure. Traoré has greatly expanded the ranks of the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP in French), a civilian militia that operates alongside the military. Phone calls and data usage are now subjected to a “war tax” to fund the troops at the front. Such acts are accompanied, as it often happens in wartime, with a heavy dose of patriotism.

‘The environment has become much worse’

Between his sovereignty discourse and modeling after with Sankara, Traoré has won a group of loyal vocal supporters among young residents of Ouagadougou. Every night, groups of young men station themselves at major intersections, stopping those they deem suspicious to check their documents.

When gunshots rang out one night last March, they descended on central Ouagadougou to protect Traoré from what they feared was an imminent coup.

One of Traoré’s informal advisers who also is the director of a pro-government civil society organization told me that such actions show the current government has the support of the people.. “These young people see that our president is bringing real development and peace to our country,” he said.

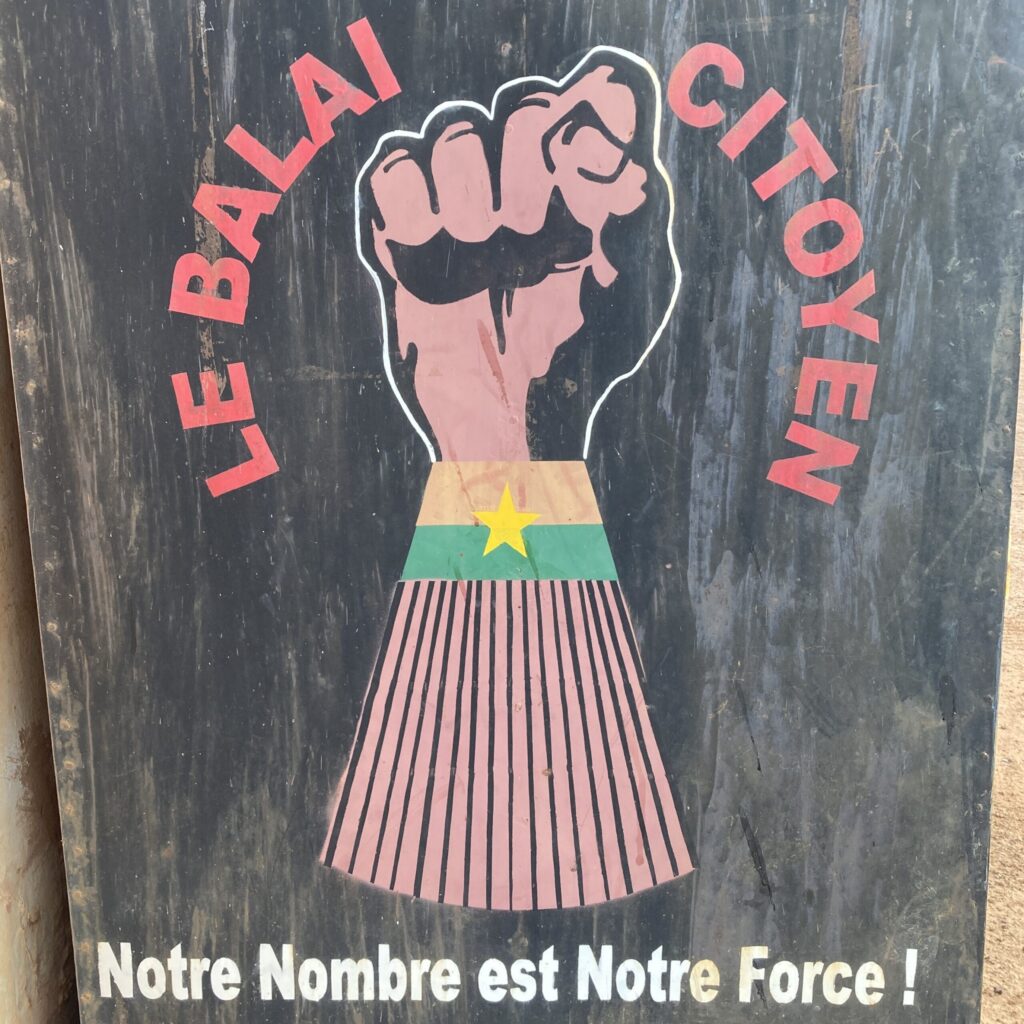

Not everyone shares his rosy perspective, however. Toward the end of my stay, I met with a spokesperson for Balai Citoyen, a civil society group that played an important role in the protests that led to Compaoré’s downfall in 2014. It has since rallied around everything from opposing high energy rates to providing more supplies for troops at the front and calling for accountability for massacres of civilians. The spokesperson, who asked not to be named, began by commending the new government for prioritizing support for front-line troops and instilling a sense of sacrifice and patriotism in Burkinabe.

But he also said people are growing concerned about the increasingly repressive atmosphere in the country, particularly a growing “with us or against us” attitude on the part of Traoré and his supporters. Those who voice any criticism of the government today are immediately smeared as opponents and silenced, he lamented.

“In the past, it was known institutions that menaced us,” he said, describing the arrests and attempts at silencing his group faced under previous governments. “Now it is unknown bodies that are harder to hold accountable, like these youths at the roundabouts.”

As is often the case, journalists were among the first victims of the recent crackdowns, as I heard from a member of the National Center of the Press Norbert Zongo, an association of Burkinabe journalists dedicated to fighting for press freedom.

“It has never been easy to be a journalist in Burkina Faso,” he told me. “But the environment has become much worse over the last year.”

Soon after the government banned French media and expelled foreign journalists in early April, it set it’s sights on local independent outlets. The newspaper L’Evenement was unexpectedly hit with heavy fines by government tax collectors that temporarily forced it to close. Omega radio was suspended for a month after airing an interview with an opponent of the military government in Niger. Ministers have sued critical journalists and threatened them on social media. Old laws that forbid journalists from reporting on terrorist attacks without the permission of the state are now being enforced for the first time. The head of the High Council of Communications, once elected by its members, is now directly appointed by Traoré.

“We know we are in a war,” the journalist said. “But you cannot justify everything with war.”

Meanwhile, there have been increasing reports of disappearances of government critics. In April, Moussa Thiombiano, known as Django—a former leader of a self-defense militia, musician, and one-time negotiator with jihadists—was kidnapped in his hometown of Fada-Ngourma. Later that month, security forces seized a prominent imam from the town of Bobo-Dioulasso. Neither has been seen since.

Instead of simply disappearing critics, the government has also begun to force some of them to join the war effort. A few days after publicly questioning the military’s strategy in March, the president of a civil-society group named Boukaré Ouédraogo was arrested and forced to enlist in the VDP.

After writing on Facebook that troops fighting at the front should not be confused with the “constitutional deserters” in Ouagadougou (a reference to Traoré and other soldiers in the capital), another critic, an anesthesiologist name Dr. Louré, was “requisitioned” by the military and sent to the front. Since I returned from Ouagadougou in October, the government announced that two members of Balai Citoyen and an activist focused on Fulbe issues named Dawda Diallo were also being sent to the front.

More generally in Ouagadougou, particularly in Fulbe communities, there is a sense you are always being watched. When I visited the city last July, I was able to walk around the Hamdalaye neighborhood, which is predominately Fulbe and hosts a number of people who have fled the war, and speak openly with people. This trip, I was warned that would be impossible.

“They are being watched,” a Burkinabe man who organizes help for displaced people told me over the phone. “The government is afraid they will tell foreigners there is a genocide against Fulbe.”

Even when we arranged for a trusted taxi driver to bring interviewees to a neutral location recommended by Burkinabe human-rights activists, they cancelled at the last minute, fearing to be seen with a foreigner.

“The sun is not the only thing that is hot in Burkina Faso,” the humanitarian said not so cryptically.

Score-settling on the front line

Ironically, government repression intended to silence criticism and maintain support for the regime is actually steadily sapping the junta’s popularity. By dividing people into “patriots” and “non-patriots,” Traoré is alienating groups that once supported him. Among such actions the spokesperson for Balai Citoyen mentioned were death threats from Traoré partisans toward trade union members who recently called for protests against the repressive environment.

“These people are not wholly against the government,” he said. “If you are not willing to engage in dialogue with people who disagree with you, you will eventually make everyone your enemy.”

Repression isn’t the only factor draining the regime’s credibility. Traoré came to power because of frustration in the military and among civilians about the poor state of the war effort. If it were going well, Traoré might be able to repress dissent with no loss of support. However, his military strategy has yet to significantly degrade the insurgents, and discontent appears to be on the rise again.

Divisions within the army and between military and civilian leaders are not new in Burkina Faso. Since the beginning of the war in 2016, the military has faced serious problems acquiring basic equipment. It had previously relied on the French for air strikes and special forces operations.

As insurgents isolated and expelled security services from rural areas in the north and east, the military suffered a series of humiliating deadly defeats, exacerbating divisions between military and civilian leaders. It is no coincidence that both Damiba and Traoré’s coups were preceded by—and justified with—spectacular military losses.

Traoré had announced the expansion of the VDP program within a month of taking power, including the recruitment of 50,000 new VDP to aid the war effort. The military had previously relied on civilians voluntarily approaching the authorities to enroll in the program. Under Traoré, the authorities have been more proactive, visiting small towns and signing up VDP on their own.

“Unlike soldiers who might not know an area, the VDP know the terrain and the people,” the director of the pro-government civil society said. “So there are many advantages” to local recruits.

The government has also sought out more resources for the military. When Western powers declined to provide light weapons he requested for the VDP, he approached Iran, North Korea and other more willing vendors. The air force received a shipment of five Turkish-made Bayraktar drones in mid-2022, which Traoré has since made a centerpiece of the war effort to some effect.

There are some places where the regime’s approach appears to be working. The government has secured the road to Bobo-Dioulasso and made gains in rural areas around the town of Kaya 60 miles from the capital. Sources in Djibo say air strikes have put the insurgents, who control rural areas outside the town, on the back foot. During a massive attack on November 26th, alQaeda-linked fighters succeeded in entering and looting the military base but were ultimately repelled by Bayraktar drones, leading to the deaths of dozens of insurgents.

But insurgents have also opened new fronts in the center-east region and consolidated their control in the east during the last year. More towns have come under jihadist blockade—supplied only by air bridge or occasional military convoys—than before Traoré came to power. According to Refugees International, an independent humanitarian organization, an additional 1 million people, some 20 percent of the population, require aid in 2023 compared to the year before.

Mobilization of the VDP under Traoré has added another dimension to the conflict’s dynamic. A VDP commander from the east told me the program’s expansion has resulted in “score-settling”—new VDPs using their enhanced status to attack community rivals—that the military is unable or unwilling to stop. Fulbe asylum seekers I spoke with in northern Ghana in August who had fled the violence in southeastern Burkina Faso described what can only be called ethnic cleansing.

Insurgents have responded to the VDP mobilization by engaging in collective punishment of their own, clearing rural villages where VDP are present and imposing blockades on large towns. Both government and insurgent tactics have resulted in horrific civilian causalities, population displacement and a general deepening of the misery, leading to such grim milestones being listed as the “most neglected displacement crisis” by the Norwegian Refugee Council.

Who’s winning and losing?

Meanwhile, every night Burkinabe news outlets announce the military has “neutralized” dozens of “terrorists.”[3] But some are beginning to ask questions.

“Is there a running tally of how many terrorists the government is claiming to have killed?” a journalist based in the northern capital of Dori asked rhetorically. “If they have supposedly killed at this point thousands of terrorists, how are these people still attacking us? Either they are lying or the terrorists are recruiting more than ever before.”

Furthermore, he pointed out, while the government lists the alleged number of insurgents killed, officials never speak about how many towns have been liberated.

The media’s boosterism is starting to frustrate troops on the front, the VDP commander from the east told me. “They are being killed every week, but it is never in the media,” he said.

Burkinabe humanitarian workers, as well as civilians who are close to soldiers in their towns, confirmed the growing dissention in the ranks. Just a week before I arrived, an alleged coup attempt by the police prompted a purge of the top ranks.

“While the special forces guard the president in the capital, the soldiers and the VDP are dying on the front line,” an aid worker from the north told me. “This will always create tensions and division.”

One of my biggest takeaways is how different life is for residents of the capital compared to those living outside major towns. When I asked the VDP commander what he felt when he saw how people were living in Ouagadougou, he joked that he wanted to slap me for posing the question.

“The gap is too much,” he said. “For five months, we have no electricity. No cold water or beer. All we can do is charge our phones with solar panels.”

The journalist from Dori went a step further, joking darkly that some days he wishes for a terrorist attack in Ouagadougou to make clear to people there what the rest of the country is going through.

No resolution appears to be within sight. While the problems that bedevil Burkina Faso predate the war, it will be impossible to address the country’s structural underdevelopment, poor government services and failing economy while a third of the country is controlled by armed groups.

Mass mobilization and more balanced international relations could help unite the country and acquire resources needed to turn the tide of the war. Reining in the VDP, relaxing repression and consolidating the state’s position in areas it controls would be equally important.

Eventually, opening some kind of dialogue with elements of the militant groups, however politically fraught, will be necessary to end the war. But it is hard to see any such steps being taken under the current leadership. Until then, Burkinabe, particularly those in hard-to-reach rural areas, will continue to suffer.

Endnotes

[1] Although that didn’t stop Air France from selling tickets. Later, it canceled flights and forced customers to jump through multiple hoops to get a refund, as I found out before my trip.

[2] As Brian Peterson points out in his excellent biography, Sankara was firmly against cults of personality. By the time he was assassinated in 1987 by his former friend Blaise Compaore (with significant support from neighboring Ivory Coast), his fierce dedication to his principles had alienated Burkinabe elites. It was not until after his death that he became feted for his many achievements.

[3] The journalist working at National Center of the Press Norbert Zongo said the military manages WhatsApp groups to which they distribute video and text to journalists that is sometimes used verbatim.

Top photo: Captain Ibrahim Traoré welcomed at the Ouagadougou airport after the Russia-Africa summit in 2023 (Wikimedia Commons)