In my first piece for the New York Times, I write an homage to the great Alexandrian scholar Mostafa el-Abbadi, who passed away in February. Several obituaries of el-Abbadi appeared in Egyptian newspapers, but most merely consisted of his curriculum vitae. No remembrance captured his colorful disposition and feisty erudition, let alone his ambivalent relationship with the authorities and his role in reviving Alexandria’s library.

By way of a brief background, I had the honor of meeting Professor el-Abbadi in August through his grandson, Mostafa Heddaya, who is a New York-based arts critic and a doctoral student at Princeton. I happened to be in Alexandria for a research trip, and Heddaya invited me to his grandfather’s Mediterranean apartment for an afternoon tea.

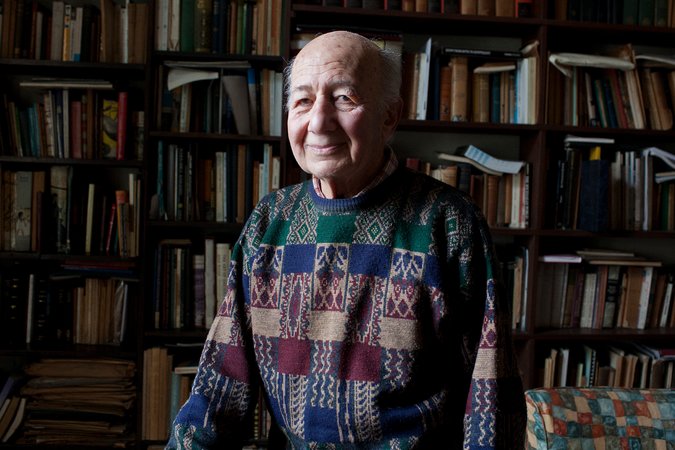

When Professor el-Abbadi came out from his chamber into the book-filled sitting room, he joined our conversation without missing a beat. He was affable and warm, inquiring about my writing and research. With a smile, he showed us a recent peer-reviewed essay he had published in the journal of the Archaeological Society of Alexandria; it had apparently made a splash at a recent academic conference in Europe.

Heddaya contacted me last month to let me know that his grandfather had passed away. The azza, the Islamic bereavement ceremony, would be held the following day in Alexandria.

In an annex to the Ibrahim Mosque, a few blocks from el-Abbadi’s apartment, scores drank coffee or tea in silence as recordings of Islamic scripture played on a loudspeaker. Men and women sat together, as the family had requested that the partition be removed. Sticking out among the family members, former students, and scholars was a representative from President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi’s Office.

When I decided to write an obituary for el-Abbadi, I spent a week interviewing colleagues, friends, relatives, and former students. There is so much that didn’t make it into the final article—that he had an Arabic poem to recite for any situation, that his presentation on ancient papyrus remains influential to one senior historian. There is also his kind spirit, his humility and love for sharing knowledge of antiquity with everyone he met; his intellectual partnership with his wife, who was also an acclaimed scholar.

His story deserves a wide audience, and I am humbled to have served as rapporteur.

FEB. 28, 2017

CAIRO — Mostafa A. H. el-Abbadi, a Cambridge-educated historian of Greco-Roman antiquity and the soft-spoken visionary behind the revival of the Great Library of Alexandria in Egypt, died on Feb. 13 in Alexandria. He was 88.

His daughter, Dr. Mohga el-Abbadi, said the cause was heart failure.

Professor Abbadi’s dream of a new library — a modern version of the magnificent center of learning of ancient times — could be traced to 1972, when, as a scholar at the University of Alexandria, he concluded a lecture with an impassioned challenge.

“At the end, I said, ‘It is sad to see the new University of Alexandria without a library, without a proper library,’” he recalled in 2010. “‘And if we want to justify our claim to be connected spiritually with the ancient tradition, we must follow the ancient example by starting a great universal library.’”

It was President Richard M. Nixon who blew wind into the sails of Professor Abbadi’s ambitious proposal. When Nixon visited Egypt in 1974, he and President Anwar el-Sadat rode by train to Alexandria’s ancient ruins to observe their faded grandeur. When Nixon asked about the ancient library’s location and history, no one in the Egyptian entourage had an answer.

That night, the rector of the University of Alexandria called the professor and asked him to prepare a memo about the Great Library’s rise and fall.

The task, he said later, made him realize how deeply the ancient library resonated, not only with Egyptians but also with many around the world who shared his scholarly thirst.

Backed by the university, Professor Abbadi began developing plans for a new research institution and ultimately persuaded the governor of Alexandria, the Egyptian government and Unesco, the United Nations educational and cultural organization, to lend their support.

In 1988, President Hosni Mubarak laid the foundation stone for what would become the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a $220 million seaside cylindrical complex. Designed by the Norwegian firm Snohetta, it comprises a 220,000-square-foot reading room, four museums, several galleries, a conference center, a planetarium and gift shops.

It opened in 2002, hailed as a revitalization of intellectual culture in Egypt’s former ancient capital, which is now its often neglected second-largest city.

“With the founding of the new Bibliotheca Alexandrina,” Professor Abbadi wrote in 2004, “the ancient experiment has come full circle.”

The professor did not share fully in the glory. He, like other scholars, had been critical of some aspects of the finished library and maintained that the builders had been careless during the excavation, unmindful of the site’s archaeological value.

When the library was officially opened, in a ceremony attended by heads of state, royalty and other luminaries, he was nowhere to be seen. He had not been invited.

Mostafa Abdel Hamid el-Abbadi was born on Oct. 10, 1928, in Cairo. His father, Abdel-Hamid el-Abbadi, was a founder of the College of Letters and Arts of the University of Alexandria in 1942 and its first dean.

Mostafa el-Abbadi earned a bachelor’s degree with honors there in 1951. A year later, he enrolled at the University of Cambridge on an Egyptian government scholarship. He studied at Jesus College under A. H. M. Jones, the pre-eminent historian of the Roman Empire, and earned a doctorate in ancient history there in 1960.

Two years before, in Britain, he had married Azza Kararah, a professor of English literature at the University of Alexandria, who had earned her doctorate at Cambridge in 1955. She died in 2015.

Besides his daughter, Professor el-Abbadi is survived by a son, Amr, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara; a sister, Saneya el-Abbadi; three brothers — Hassan, a former Egyptian ambassador to Thailand and Cuba; Hani, a former Egyptian ambassador to Sri Lanka; and Hisham — and five grandchildren.

Professor Abbadi and Professor Kararah returned to Egypt in the 1960s to be lecturers at the University of Alexandria. They held many visiting fellowships and appointments throughout their careers. From 1966 to 1969, they taught at Beirut Arab University in Lebanon.

During school holidays, they would pile their two children into the back seat of their Volkswagen Beetle and drive to archaeological sites in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, singing songs along the way. At their home they played host to the novelists Iris Murdoch, Amitav Ghosh and Anita Desai, who wrote the couple, as well as their cat Cleopatra, into her novel “Journey to Ithaca.”

In the 1970s, Professor Abbadi was perhaps the only Egyptian scholar focused on Greco-Roman history in a country where Pharaonic studies was the dominant discipline for classicists.

“For people who do what I do,” said Roger Bagnall, a professor of ancient history at New York University, “he was the port of call in Egypt.”

Professor Abbadi became a leading authority on the original library, a grand repository of the ancient world’s accumulated knowledge as well as a research institution. Established around the third century B.C. by Ptolemy I, it was destroyed sometime in the first century B.C.

Professor Abbadi’s book “Life and Fate of the Ancient Library of Alexandria,” published in 1990 by Unesco and translated into five languages, continues to be widely cited by scholars.

In that book, one of several he wrote or edited, he blamed Julius Caesar for the ancient library’s destruction, countering one politicized narrative that holds Arabs responsible.

In interviews and papers, Professor Abbadi asserted that although it was not the world’s first library, it was the first universal library, housing an estimated half-million texts from many countries and in many languages, including Aristotle’s works and original manuscripts by dramatists like Sophocles.

“He was without doubt the doyen of Alexandria,” Dorothy Thompson, a Cambridge fellow and honorary president of the International Association of Papyrologists, said of Professor Abbadi. “He made Alexandria known in the English-speaking world in the 20th century.”

In 1996, he was elected president of the Archaeological Society of Alexandria, founded in 1893. He lectured throughout the world and received many academic and government honors.

In an email, the biographer Stacy Schiff, author of the acclaimed “Cleopatra: A Life,” cited the novelist Lawrence Durrell, author of the tetralogy “The Alexandria Quartet,” in writing of Professor Abbadi. “Every bit the representative of what Durrell called ‘the capital of memory,’” she said, “he seemed to hold whole civilizations in his head.”

When the library opened in 2002, Professor Abbadi donated a rare 16th-century copy of “Codex Justinianus,” the codification of Roman law under Justinian I in the sixth century A.D. It was one of the first books to sit on the new library’s shelves. Before his death, the professor donated his and his wife’s roughly 6,000 books and academic papers.

Yet during the construction and afterward, he found the project wanting. “We have a great name, fortunately,” he said of the library in an interview with The New York Times in 2001. “The challenge is living up to it.”

He found the library’s book collections for students inadequate. And the construction, in his view, had been done without proper archaeological surveys and excavation, even though the site was in what was called the palace quarter in the era of the Ptolemaic kings.

Standing on the balcony of his apartment nearby, he videotaped bulldozers digging up historical artifacts and plunking them into the sea.

“The ensuing scandal forced them to stop work and permit an emergency salvage archaeological dig,” Max Rodenbeck, then the Middle East bureau chief of The Economist, recalled.

Sure enough, a large mosaic of a sitting dog, from the second century A.D., was discovered at the site. It is now in the library’s antiquities museum.

Professor Abbadi had persuaded the Egyptian authorities to establish that museum, an endeavor that took him to dusty government storerooms and archaeological sites as he built out the collection. In a Luxor crypt that had not been opened in three decades, he stumbled upon ill-preserved wooden funerary boxes from King Tutankhamen’s tomb.

He also raised money to acquire hundreds of volumes of texts from early Christianity.

Yet the government did not invite Professor Abbadi to the library’s official opening, apparently because of his criticism of the project.

“No Egyptian newspaper mentioned his name at all,” said Prof. Mona Haggag, a former student of his and head of the department of Greek and Roman archaeology at the University of Alexandria. “It became the project of the presidents, of the people who cut the rope, the people who stood on the front stage, and not of Mostafa el-Abbadi.”

As his “Life and Fate of the Ancient Library of Alexandria” was distributed among the guests at the event, he passed the day in his own library, at his home overlooking the Mediterranean.

A version of this article appears in print on March 4, 2017, on Page A15 of the New York edition with the headline: Mostafa el-Abbadi, 88, Historian of Ancient World Who Led Alexandria Library’s Revival.