BANGDONG, China — “Comrade Ma Tai!” boomed Chairman Yang, calling me by my Chinese name. “May I call you comrade?” he added, a grin spreading across his round face.

“I’m not a Party member, so I’m not sure,” I replied tongue-in-cheek.

“You don’t have to be, besides, we can be closer friends as comrades,” he assured me.

“Well then, yes, Comrade Yang, you may,” I agreed with a smile.

We sat in a government office building along with the three other top leaders from the township of Potou, a community of several thousand people scattered across the mountains of rural Yunnan, China’s southwestern-most province. The administration oversees Bangdong village, where I live, so I often see Chairman Yang and the others around town, usually at the vegetable market that rotates through every five days.

Yang passed out cigarettes to his comrades and they clicked their lighters. A “No Smoking” sign hung by the door.

“Comrade Ma Tai, a trade war wouldn’t really affect us,” continued Yang, my now-closer friend. “We are too far from anything.”

China’s population is still roughly 50 percent rural and, in his consolidation of power, President Xi Jinping has been careful to cultivate the support of the countryside and places like Potou. Now, as international trade delegations oscillate between a deal and no deal, and tensions ratchet up between Beijing and Washington, what do rural Chinese think of their country’s growing influence, the burgeoning global competition with the United States and President Trump?

A series of interviews reveals no lack of opinions, some informed and others ignorant. But almost without exception, rural Chinese see the United States as an aggressor brandishing both tanks and tariffs, while China and its peaceful rise occupy the moral high ground.

“There will most definitely not be a trade war,” Mayor Kong said confidently. “Both sides would suffer.” He wore the thick-rimmed glasses of an academic and the digital-patterned camouflage pants of a military man. “When we open our doors,” Kong continued, “good things can come into our China—like ken-de-ji.” He was referring to the Chinese name of KFC, a transliteration of Kentucky. Ken-de-ji is ubiquitous across China (along with unfortunate copycats such as KLG, FCK and Obama Fried Chicken) and, for many, it is quintessential American cuisine. “When we open our doors,” Kong added, “good things can also go out to your America.” I wondered if he meant Panda Express.

Mayor Kong spoke at a deliberate pace. He had been a teacher for many years before joining the government, so bullet-point lectures were a strength. Now, the Party provided the curriculum and Kong delivered:

• “The whole world is one family with a shared destiny.

• If your president closes the doors on trade, it hurts everyone, especially the common people.

• We must first have peace, only then can we have development.”

I glanced around the office as he preached the gospel of free trade. The wall was covered with slogans and posters highlighting the work ahead: Closely Connect the Party and the People, Rural Revitalization Targets for Lincang Townships and Villages, Status of Bangdong’s 11th Session of the National People’s Congress Bureau. Some might interpret Kong’s free-trade message as heretical to the Party’s manifesto. However, dialectical materialism—in which President Xi is said to be a true believer—resolves this tension by integrating Marxist ideology and economic liberalization for an ever-evolving society. The result is sinocized Marxism or socialism with Chinese characteristics. And for most Chinese citizens who forego the mental gymnastics of reconciling the apparent contradictions, the tension is as easy to embrace as a lit cigarette near a “No Smoking” sign.

Pax communista

Yang’s sentiment that Potou is too remote is common. “Never mind a trade war, even an actual war wouldn’t affect us here,” said Shi Biang’er, a young mother who used to work in a foreign cafe in the provincial capital. “People here are like frogs in a well, their perspective is limited,” she added. “They’re mostly concerned with keeping up with others in the village: selling more tea, building a new house or buying a new car.” A talent show blared on a television as we chatted and Biang Er confessed to disliking the news. “After working hard all day, we just like to watch our soap operas. Beijing is distant and international politics isn’t relevant to our lives.”

The rotating market comes through Potou township every five days, bringing with it a flood of farmers and produce from the surrounding countryside

Master Kang, then, is a bit of an anomaly in the village. He runs the shop—what I call Kang’s Convenience—at the intersection of Bangdong’s only road and the cobblestone road to Potou. If there’s any news passing through the area, Master Kang is privy. I stop by for one of our regular chats and interrupt his nightly news program.

“I don’t blame Trump,” he said. “It’s his job to serve the American people’s interests. President Xi does the same for us.” Kang’s clear eyes and wispy goatee give him a sage-like appearance. “Serve the people,” he added, quoting Chairman Mao. Trump may not know he’s operating by the Communist Party’s most popular slogan.

But where Kang does take issue with the United States is in its foreign policy: “The US likes to interfere in other country’s affairs.” Sometimes that’s been to the world’s—and even China’s—benefit. America is often at the forefront of reconstruction efforts in war-torn countries. Trump is helping broker peace on the Korean Peninsula. And even closer to home, the United States was a friend to China in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in the lead up to World War II. However, Kang also said the Americans are too quick to take sides and go to war.

“The US foments dissent,” he said. “It likes to get other countries to fight among themselves so that the US can sell them weapons and make money.” That is a common perception among the villagers, and a stark contrast to how they perceive their own country. “China is a peaceful country,” one said. “We would never start a war,” said another. With China’s military buildup, outside observers might find that hard to believe. But China’s self-declared “peaceful development” (previously “peaceful rise”) attempts to minimize any perception of threat and reinforce China’s aversion to war, something students of Chinese history understand well.

China’s recent history is rife with war against powers both foreign and domestic. Beginning in 1839 with the First Opium War, China was more-or-less continuously at war for over a century until the ceasefire of the Korean War in 1953. Conflicts were with the British, French, Americans, Japanese and Koreans, and included several domestic rebellions and almost three decades of civil war between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Nationalist government (KMT). Even after Communist victory in 1949, China suffered “internal turmoil” (内乱) until the economic reforms known as Reform and Opening in 1978 led by Deng Xiaoping. “War destroys development,” Master Kang pronounced. In contrast, China has enjoyed peace and unprecedented economic growth over the last 40 years as it has focused on its domestic agenda.

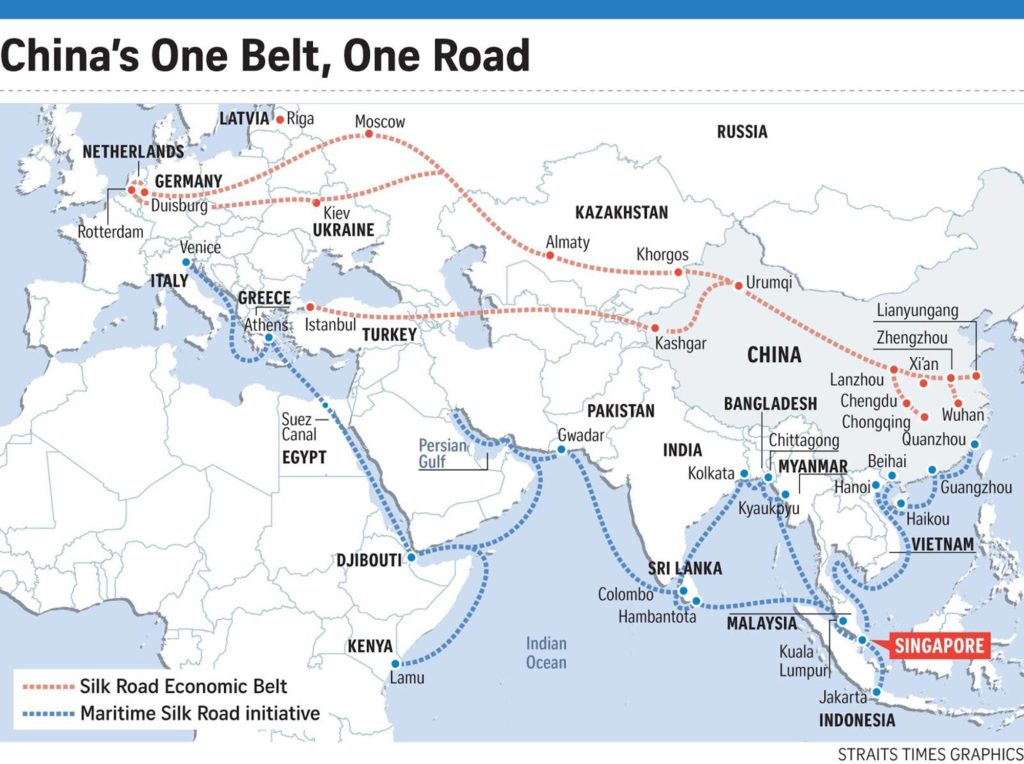

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is projected to connect two-thirds of the world’s population at a cost of over $1 trillion

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is projected to connect two-thirds of the world’s population at a cost of over $1 trillion

“There’s no need to go to war. We can solve everything by talking,” one young man said. “Or with moh-nee!” he added, emphasizing money in English and rubbing his fingers and thumb together. China has doubled its foreign affairs budget in just the last five years under Xi, and that doesn’t include investment, infrastructure development or financing that are also leveraged to achieve China’s foreign policy goals.

In April, the Dominican Republic cut off diplomatic relations with Taiwan in favor of the government in Beijing. China says there were no economic pre-conditions, but many speculate the estimated $3.1 billion in infrastructure projects now slated for construction influenced the switch. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a network of infrastructure development projects, is projected to reach two-thirds of the world’s population, stretching from western China to Africa and Europe. With a projected price tag of $1 trillion, it is poised to improve the infrastructure landscape of the world—and dramatically extend China’s influence.

Peaceful development may be easy when a country has no interests abroad. But with China’s expanding reach into Africa and along the proposed Belt and Road Initiative, the country’s decades-long policy of non-interference will be increasingly difficult to maintain. Last year, China opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti (eight miles from a US base); it also took out a 99-year lease on a Sri Lankan port—for commercial purposes, it says, although it is also capable of servicing the Chinese navy. As the lines between economic and security interests become increasingly blurred, some fear the responsibility for maintaining China’s peaceful rise may fall upon the military.

A night at the movies

In early March, “Amazing China” (厉害吧,我的国) hit theaters across the country. Released by state broadcaster CCTV, the film highlights “the development and achievements of the Party” over the last five years. It debuted one day before the opening session of the National People’s Congress and, after less than two weeks in theaters, it became China’s top-grossing documentary of all time, bolstered in part by compulsory viewings for China’s 90 million or so Party members. Given the hype, Comrade Ma Tai also ventured two hours into Lincang, the nearest city, for a Monday evening viewing.

Lincang is a non-descript city of 350,000 set in a small river valley in southwest Yunnan. Just 15 years ago, fields of corn and cabbage, broad beans and rapeseed still filled the valley; now, housing developments and shopping centers have moved in, complete with a Walmart and an authentic ken-de-ji. “Amazing China” was playing at Everlasting Foundation Plaza, the new home of Sam Walton, Colonel Sanders and Starry Sky Cinemas. I joined fifteen others, mostly twenty-somethings, in the sparsely-filled theater. One played on her phone for most of the film. Another not-so-inconspicuously snapped photos of the foreigner. But the rest of us were focused on the 90 minutes of China’s incredible achievements in HD.

“Amazing China” features an automated shipping port operated by just nine people. Port development is a critical part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative to build infrastructure around the world

Sweeping panoramas captured newly-built highways, high-speed rail and record-breaking bridges. A deep-voiced narrator told of Chinese advances in space and ultra-deep sea exploration. A montage highlighted China’s growing military capabilities on land and sea with a fatigues-clad President Xi spurring troops to “defeat any foes that invade our territory.” Media footage showed the opening of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, China taking the lead on global climate change and Xi “bringing China’s development experience to Africa.” Xi played the lead role throughout, exhorting chip manufacturers and rocket scientists, visiting relocated Tibetans in their new homes and encouraging students to pursue “the Chinese Dream.” The documentary with propaganda characteristics did its job. “The Communist Party is great!” exclaimed a movie-goer. “I’m proud, excited!” another responded. I myself left Everlasting Foundation Plaza impressed and inspired. The China projected on-screen and onto the world stage is technologically advanced, militarily capable and globally assertive.

But some in China say Beijing’s propaganda has been too effective. “China is overconfident,” says one foreign-affairs specialist I spoke with, who requested to not be identified. “China pretends to be strong in order to fuel nationalism,” he elaborated. “It flashes its money and flexes its muscle so the US loses confidence, but China has gained more confidence than it deserves.”

Chen Wenling, the chief economist at the China Center for International Economic Exchange (CCIEE)—one of China’s most influential think-tanks—agrees. “The media has done a disservice by playing up a strong China,” she said in a recent interview with Jiemian news. As a result, many Western countries now have the illusion that China is number one. “However,” Chen reminded readers, “we can’t mistake the 2050 blueprint as one we have already realized.” The blueprint refers to the Party-led vision announced last fall to develop into a “great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful.” Regardless of perceptions at home or abroad, President Xi’s task, then, is to remain focused on the domestic agenda while avoiding wars over tariffs—or, worse, with tanks.

Kang’s inconvenient truth

Powerful. Big boss. Number one. That’s how Bangdong residents describe the United States to me, usually along with a thumbs up. But, as Chen warns, villagers also see China as increasingly able to compete with America as equals. “The US is like an elder brother,” Master Kang said. “He doesn’t want baby brother to grow bigger than he. But there’s nothing he can do about it.”

Master Kang’s shop—which I affectionately refer to as Kang’s Convenience—decorated for Chinese New Year

Master Kang’s shop—which I affectionately refer to as Kang’s Convenience—decorated for Chinese New Year

Master Kang and I chatted late into the night and the single bulb in Kang’s Convenience was soon one of the last lights on in the village. The fluorescent light was cold and left half of Kang’s face in darkness. “China doesn’t want any kind of war. We are still developing. But we aren’t afraid of war either.” Again quoting Chairman Mao, Kang said: “Leave me alone and I’ll leave you alone; but attack me and I’ll certainly counter.” Kang’s words were weighty, but pragmatic. We sat silently for a moment as his words hung in the air, thick with the tension between foreign policy and friendship.

“But you and I are just people,” he concluded. “It doesn’t affect us and we can’t change it. That’s up to our governments.”