SINGAPORE — In Little India, where sari-draped mannequins share narrow arcades with older men hemming and hewing over streetside sewing machines, two brown-skinned men walked shoulder-to-shoulder in front of me. Even as sweat began to pool on my forehead—the winter solstice provided no relief from the island nation’s sticky humidity—the two pressed closer. One man’s hand cradled the bottom of the other’s backpack. A useless gesture; it seemed to lift no weight from his companion’s shoulder.

I watched as his hand briefly grazed parts of the other’s body. The love handle on the far hip, caressing as though strumming a soft ballad. Up to the nape of the neck—a quick massage. Back down, as the two men’s fingers tapped against one another, tips interweaving for seconds before releasing again, the midday sun streaming through the gaps between them.

They stopped before a jeweler’s stall and peered into a cabinet of rings by the glass entrance. Taking turns, they used their chins to direct each other’s eyes to various designs. Their bodies huddled so tightly that their proximate hands disappeared into a mess of limbs, sleeves and fanny packs—a precious warmth protected from the world’s watchful eyes. They eyed the jewelry for over a minute, enough time for me to hustle past them, flashing a smile through the reflection of the windows.

I have no idea if those two men were actually a couple. But if so, theirs was a familiar dance around public affection. I remember when I would steal away into empty high school staircases or the last aisle of the supermarket just to hold a boy’s hand and the butterflies of a honeymoon romance flitting in and out of the stranger’s gaze.

But here, in a state that has policed queer identities within a broader project of social control, I wondered if these men scanned the streets around them for familiar eyes before choreographing their affection. Or if they thought about the police raids that continued into the early 2000s, when plainclothes officers posed as hookups to cane and arrest gay men under Section 377A—a British colonial-era penal code from the 1930s that criminalized consensual gay sex in both public and private settings.

I wondered if these men became more courageous after the anti-sodomy law was finally repealed in 2022, when even Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam admitted: “It’s not fair that gays have to live this way.” That is to say, as criminals.

I wondered what it meant to be in love, let alone live, with the state as a third party—a constant voyeur, its long shadow guiding and gazing upon them.

* * *

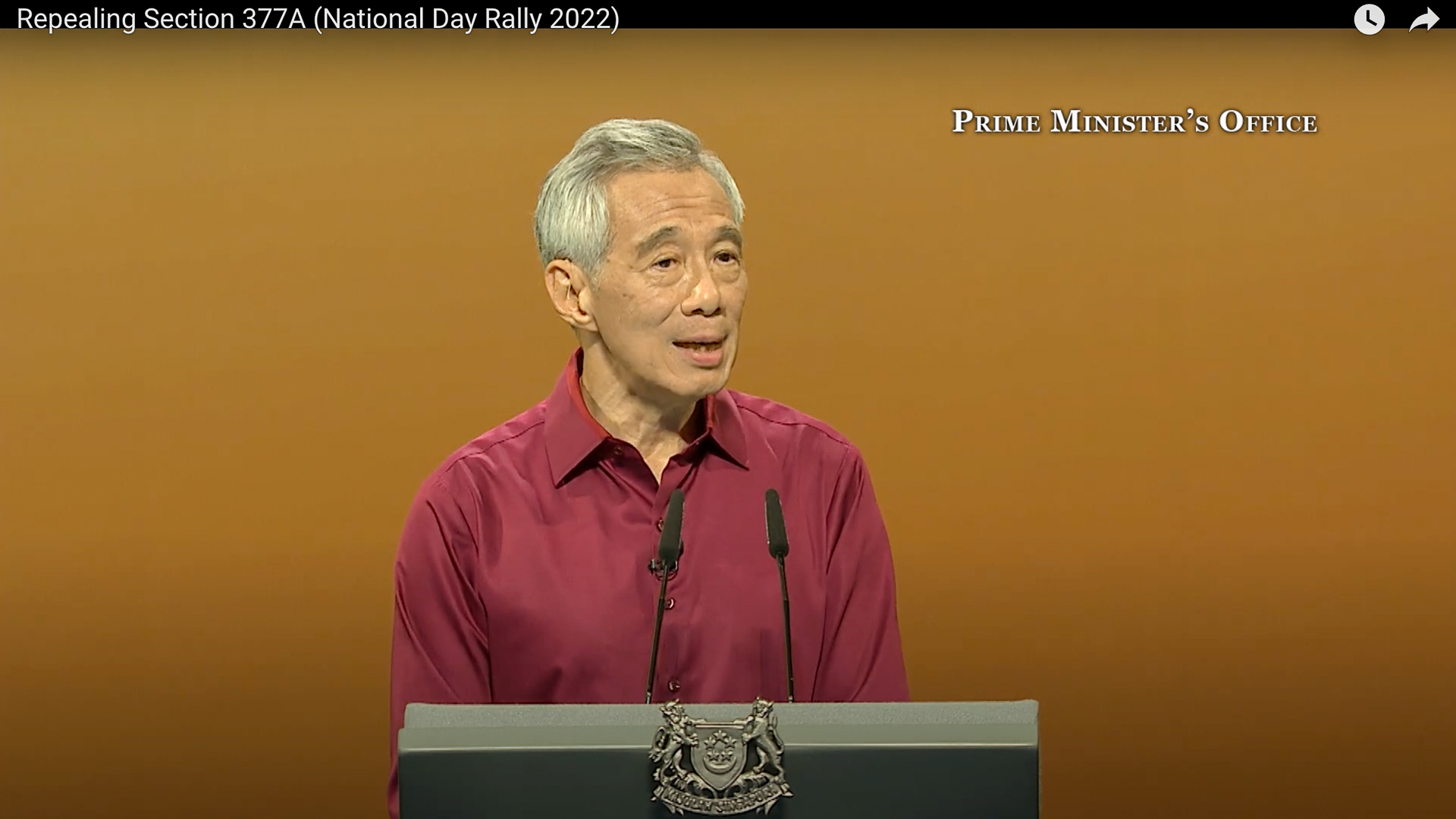

There was something chilling about then-Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s delivery of his 2022 National Day Rally address. When he announced the repeal of Section 377A, his pacing was tempered, his tone dispassionate, his facial expressions nearly unmoving. In one breath, he affirmed that “there is no justification to persecute” the private sexual behavior of gay men. In the next, that “only marriages between one man and one woman are recognized in Singapore.”

For many queer listeners, Lee’s speech evoked emotional whiplash from joy to tremulous silence. With the repeal of Section 377A came the passage of Article 156, which declared that the legislature—dominated by the People’s Action Party (PAP) since 1959—would control the institution of marriage. While it does not officially codify a heterosexual definition of marriage, PAP officials have been consistent and clear that Singapore is a society built on heterosexual family values. Roy Ngerng, an outspoken Singaporean human rights activist who currently lives in exile in Taiwan, wrote that repeal is “not out of genuine human rights concern for the LGBTQ community. They felt compelled to prevent same-sex marriage from becoming law in Singapore.”

In Singapore, I’d learn, everything happens for a reason. Due to the limited space on the island city-state, graves are exhumed and cremated after 15 years to make room for the next generation of death. Cars can be leased only for up to 10 years, their value depreciating year by year to regulate congestion. Marriage and the privileges it affords—the ability to adopt or recieve housing subsidies, among others—must be safeguarded because, according to the state, that is what most Singaporeans want.

Since LGBTQ+ people are a “cosmetic accessory that makes Singapore appear liberal and attractive to foreign investments and professional labor,” as the anthropologist Chris K. K. Tan wrote, they should be respected.

“Like every human society, we also have gay people in our midst,” Prime Minister Lee said in his speech. “They too want to live their own lives, participate in our community, and contribute fully to Singapore.”

* * *

As we share an icy metal bowl of chendol—a coconut milk dessert soup, sweetened with palm sugar and topped with yam paste and pandan-green strips of agar jelly—a man shows me a video tour of his newly renovated home. It is minimally brutalist, with dark-colored walls and furniture accenting the natural light streaming through tinted windows. Everything down to the powder rain feature of his shower set—which creates a “spa-like experience,” he narrates in the video—is intentional and pristine, as though straight out of Architectural Digest. In one photo on his Instagram grid, he sits amid the rubble of his apartment at the beginning of the gut-renovation process with the caption: “Bachelor pad in the making.”

Despite being 36 years old, this was the first time he had moved out of his family home, located far from his workplace in the west of Singapore. As I’d learn, that is common for queer folks in Singapore.

Nearly 80 percent of Singaporeans live in flats developed by the government’s Housing and Development Board (HDB), with around 90 percent of residents owning their apartments. This model of affordable home ownership has been the cornerstone of Singapore’s nation-building efforts since its independence in 1965. Every quarter, the government announces new, heavily subsidized “built-to-order” (BTO) flats—pristine, monochromatic high-rises that puncture the sky in fractal fashion.

However, those below the age of 35 must be engaged, married, have children or apply with other family members to qualify. The heteronormative family nucleus exists at the heart of Singapore’s housing scheme, with a 2021 National University of Singapore study finding a correlation between the rise of the BTO scheme through the 2000s and rising marriage rates. By 2020, the median marriage age for heterosexual couples was 30 for men and 28 for women, with some journalists and scholars lamenting that people are marrying for housing, not love.

But LGBTQ+ people with no possibility of marrying are viewed as “single” in the eyes of the state. The earliest they can apply for an HDB flat is when they turn 35, putting them on average five years behind their peers, not even considering extended wait times and often smaller unit sizes they face. Indeed, only last year were single buyers over 35 able to apply for a flat in any location. If LGBTQ+ couples or individuals hope to move out of their parents’ homes before 35, their options are to purchase resale flats—which, by the HDB’s estimates, can cost 25 percent to 179 percent more than an HDB flat—or private condominiums, the average prices per square foot of which are 3.3 times higher.

With Singapore consistently ranking as one of the world’s most expensive cities, together with the housing subsidies, rentals make little financial sense. Members of one gay couple in their mid-twenties mentioned that between their two incomes—of a civil servant and an international fellowship recipient—they were lucky but barely able to rent a private condominium.

Unsurprisingly, then, most queer folks stay in the homes where they grew up until they are eligible for a BTO flat. However, research by Sayoni, a volunteer-run organization by and for queer women, found that one in five LGBTQ+ Singaporeans live in hostile family environments, with few options to escape or find refuge.

Even if their home situations are not outright hostile, many queer Singaporeans remain closeted at home, accustomed to a lifestyle that balances drag extravaganzas most weekends with deep filial piety for older generations during holidays. “Coming out” is not a necessary rite of passage for gay Singaporean men, who privilege familial and social inclusion over bold announcements of their sexuality. But with this choice of lifestyle, space becomes capital—both in the financial and social senses—with saunas, public restrooms and gay bars the next best alternatives for most people to explore intimacy and sexuality.

In a state where pragmatic economic growth has dictated national social policies, my chendol date was able to buy a pocket of freedom within the sleekly designed walls of his new home. But outside those walls, even after the repeal of Section 377A, numerous ministries emphasized that there would be no change to the housing, family planning (e.g., adoption), education and media policies that currently discriminate against LGBTQ+ people.

Most recently, in early January, Singapore’s parliament passed an antidiscrimination law known as the Workplace Fairness Bill that excluded sexual orientation and gender identity as protected categories. Scholar-advocates Rayner Tan and Sugidha Nithiananthan wrote that despite government assurances that any form of discrimination is intolerable, the explicit exclusion of LGBTQ+ people “paves the way for its own two-tier, discriminatory approach to workplace discrimination.” They note that only one in 10 LGBTQ+ people choose to report discrimination, largely due to the fact that current mechanisms do not protect individuals from retaliation.

Putting all these factors together, a 2024 survey found that LGBTQ+ folks are only half as likely to be confident of meeting their basic needs (e.g., health care, housing) as other Singaporeans.

“To be queer is to do everything I can to resist the typical Singaporean pathway,” someone told me. Implicitly, yet so comprehensively excluded from so many of Singapore’s social protections, how many queer people are able to wholeheartedly resist remains unknown.

* * *

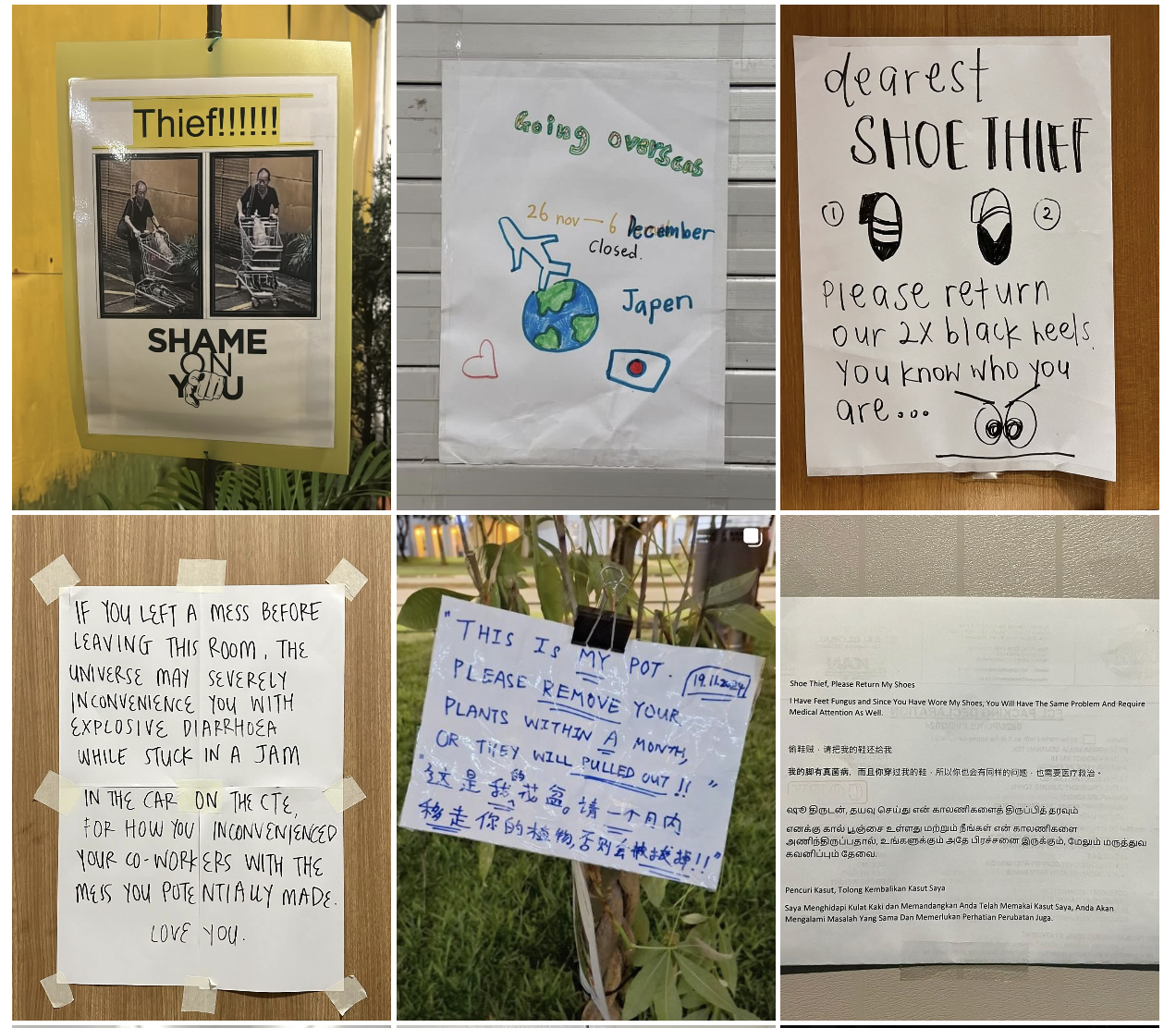

A friend described the Instagram account @publicnoticesg as quintessentially Singaporean. Created by photographer Kevin WY Lee, with more than 21,300 followers, the account is a crowdsourced visual archive of messages printed or hand-scrawled onto copy paper or cardboard. Their edges imprecisely taped or plastered down, these notices boldly protrude from orderly elevator bulletin boards and otherwise-pristine void decks—the multipurpose open areas on the ground floors of all public housing buildings, where weddings are held and children run rampant. Some are taped directly onto others’ front doors.

The messages themselves are varied, from lost items to missing pets, lovers separated to couples married, mixed in with dubious ads for childcare services and notices of food price increases. But most common are those of vexed residents, often with baffling punctuation and sporadic capitalization, incensed to aggressive in tone:

“Whoever Stole, Plucked or Damaged My Plants N Flowers Will Forever Be Bad Luck”

“dearest SHOE THIEF… Please return our 2x black heels you know who you are…”

“If you left a mess before leaving this room, the universe may severely inconvenience you with explosive diarrhoea while stuck in a jam in the car on the CTE, for how you inconvenienced your co-workers with the mess you potentially made. Love you”

While initially captivating for their humor and extremity, these messages’ ubiquity and popularity, Claire Voon noted in the independent publication Mynah Magazine, are representative not only of Singaporeans’ passive-aggressive personalities but, more insidiously, a breakdown of social engagement. “Common spaces, rather than cultivating mutual understanding, become battlegrounds and sites of entitlement, anxiety, distrust, and public shaming,” she writes. A panopticon is created by peer surveillance and frequent police reporting, with many people turning to the authorities as the immediate course of resolution.

On one hand, @publicnoticesg seems to be exceedingly honest—a record of how people really feel when freed from the pressures of being seen or confronted. Indeed, without the veneer of anonymity, independent journalist and human rights activist Kirsten Han wrote in her blog We, The Citizens, people are accustomed to “twisting ourselves into pretzels, trying to talk in legal loopholes, trying to exist in the in-between spaces, the tiny crevices that might still (for now) be safe from the reaching tendrils of broad, oppressive legislation.”

The @publicnoticesg feed put into context the exceptional nature of one protest that emerged repeatedly in my conversations.

In 2021, a short-lived, unsanctioned protest against institutionalized transphobia occurred outside the Education Ministry. Five masked protesters—some students, some not—held rainbow and Trans Pride flags as well as placards that read: “#FixSchoolsNotStudents,” “Trans students deserve access to health care and support,” “Why are we not in your sex ed?,” “Trans students will not be erased” and “How can we get A’s when your care for us is an F?”

The protest was borne of a viral Reddit post in which a transgender woman detailed discrimination from her junior college as well as the Education Ministry. The school administration took issue with her hair length and threatened expulsion if she could not fit into a boy’s uniform while undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The ministry allegedly intervened, ordering her doctor to dismiss the referral to begin HRT. “What right does the Education Ministry have over the [Health Ministry]?” she wrote.

In Singapore, protest can only take place in one location—the Speakers’ Corner, in Hong Lim Park—under police surveillance. Yet here, five protesters boldly attached their faces and names to their public notice, directly confronting the state in a departure from not only typical Singaporean behavior but also that of most other activists.

Indeed, to survive and sustain their movement under an authoritarian state, Singaporean activists have adopted what scholar Lynette Chua describes as “pragmatic resistance”—a “collectively sustained strategy” in which activists “adjust their tactics according to changes in formal law and cultural norms, and push the limits of those norms while simultaneously adhering to them.” Activists avoid breaking the law or openly confronting the government, instead appealing to political norms (such as “social harmony”) and focusing on immediate concerns.

In recounting the transphobia protest, one activist lamented to me that as soon as the protest spiraled away from more concrete issues around uniforms or hormone therapy, it lost focus and introduced risk. Not only could the protesters’ actions compromise the safety of other transgender folks but they also introduced uncertainty for activists who engage more directly with the government. Indeed, following decades of sanctioned protest, some LGBTQ+ activists now have seats at the table during closed-door consultations with the government. However, the authorities can not only close those doors but, given its tight control over the media and information flows in Singapore, can also easily paint a negative picture of activists and their causes.

Pragmatism is “about saying some things are just unchangeable,” Kenneth Paul Tan, a professor at Hong Kong Baptist University, said in a 2019 lecture. “We cannot change those things, therefore don’t try. Instead work around them. Don’t bang your head against the wall because you know your head will break, the wall won’t.”

Another activist, who is actively involved in a mainstream LGBTQ+ organization, mentioned that they did not participate due to the known consequences of an illicit demonstration. Even so, “I like foolishness—with age, we often become calcified and take fewer risks to push boundaries,” they told me.

In a climate where both the state and public are hostile to activism (e.g., direct actions, parades, interruptions at international conferences), where activists are pulled between the pragmatism of results and their more radical hopes, this multigenerational cluster of trans folks and allies audaciously tested the boundaries of respectability politics. On @publicnoticesg, “photographs of notices fail to capture the fullness of a circumstance in all its complexities,” Voon wrote. But here, five transgender folks and allies held up their public notices, sent out a press release and engaged with the media in the ensuing weeks, refusing to be placated by the government’s inaction.

Within 30 minutes of the protest, three demonstrators were arrested and the remaining two were later interrogated, as were a few bystanders. Ten months later, conditional warnings were given to the protesters, urging them not to break the law again. The Education Ministry released a statement that misgendered the original Reddit poster and did not address any issues raised, let alone that 77 percent of transgender students feel unsafe in Singapore’s education system, according to research conducted by the transnational Asia Pacific Transgender Network and the local non-governmental organization TransgenderSG.

Caught in the currents between pragmatism and radical hope, between survival under authoritarianism and the conviction that Singapore must do better by LGBTQ+ and other marginalized people, to be an activist in Singapore is to bear the psychological costs of incessant yet impossible choices.

* * *

“We Malays are known for our hospitality, which is why I offered to take you around today, even though we just met,” my afternoon companion—a gay Malay man—said. “That hospitality also led to our downfall.”

He was referring to the advent of British colonialism, as we skimmed photos of plantations and early trading ports in the Geylang Serai Heritage Gallery. The one-room space is a photographic and material archive of the Geylang Serai neighborhood, which continues to host Singapore’s largest Ramadan bazaars and serve as the center of local Malay life. As we snaked through display cases and dioramas of Malay textiles, food and festivals, his pride in his Malay identity radiated, and he recounted childhood moments when he played this game or read that comic.

But, sporadically, he would speak with that matter-of-fact tone: disarmingly straightforward, devoid of emotion.

When I asked if he was religious, he responded: “I was born into a Muslim family.”

While we shuffled through corridors of baju kurung and baju melayu—traditional Malay dresses and tunics—hanging in the market next door, he mentioned that he had been forcibly outed by an uncle and evicted from his family home during Ramadan.

“That’s why Malay men on Grindr are all headless torsos, too scared to reveal their faces.”

Fifteen years later, his family has barely inched toward acceptance. He is now in a long-term relationship, with plans to move to Australia sometime in the future.

A pause.

“Have you had putu piring?” he asked, referring to the steamed rice cakes, usually filled with gula melaka and topped with grated coconut. I shook my head, unsure if and how to continue the previous conversation.

* * *

“Repeal was simple.”

Between bites of tater tots, Clement Tan patiently fielded my free-wheeling questions about the repeal of Section 377A and its aftermath. Tan is the spokesperson of Pink Dot SG, Singapore’s most visible and recognizable LGBTQ+ advocacy organization that has hosted the eponymous Pride celebration every June since 2009. Beyond the Pride event, Pink Dot acts as a catalyst for LGBTQ+ community initiatives and spotlights the efforts of other organizations. “Despite Pink Dot’s early insistence that it wasn’t a protest, this wasn’t a claim that they could get away with for very long,” Han wrote in a narrative analysis of Pink Dot’s first decade (2009-2019).

Indeed, Pink Dot transformed from an entirely volunteer-run, non-confrontational, family-friendly picnic in Hong Lim Park to, by 2018, an event where participants write politicized slogans on pink placards and emcees declare, “Pink Dot is a protest.” At the end of a day filled with programming and communing, organizers spell out key slogans using pink or white neon torches, surrounded by a literal circle of participants dressed in pink, captured in an aerial night photo that gives visual resonance to modern Singapore’s largest civil society effort. At its height, Pink Dot attracted more than 20,000 participants—serving as a highly visible, symbolic exercise of Singaporeans’ constitutional right to assemble and express discontent in a state where public demonstration is rare and heavily regulated. By 2019, Pink Dot’s message was loud, clear and explicitly political, illuminating the words “Repeal 377A” in the heart of Singapore.

Of course, Tan knows better than anyone that Section 377A’s repeal, preceded by decades of legal advocacy and public campaigns, was anything but simple. The movement contended with years-long court challenges and the rise of openly homophobic opposition groups. While the authoritarian state claimed in 2018 that LGBTQ+ people “face no discrimination in work, housing or education,” Facebook groups with names like “We are against Pinkdot in Singapore” (WAAPD) continue to attract thousands of members and make daily posts ridiculing LGBTQ+ people. Within the LGBTQ+ community, Pink Dot faced criticism for being too fluffy, slow and normative, with tame slogans like “freedom to love.”

Nevertheless, Tan noted that “Repeal 377A” was a clear and simple call to action. It was easily digestible for Singaporean society at large and easily disseminated throughout an LGBTQ+ community that, its diversity notwithstanding, could at least agree that no identity should be criminalized.

However, since the repeal moment in 2022, LGBTQ+ advocates have faced a much more complicated question: What next? As movement lawyer Daryl Yang and scholar Joel Yew wrote in the independent Singaporean publication Jom Media, the LGBTQ+ movement “no longer has the legal totem of queer oppression around which to rally.” Now, the community is left with a buffet of legislative and policy scuffles—each of which may only prioritize a slice of the LGBTQ+ community, along identity, class or other lines. Moreover, there is now pressure to create positive recommendations, burdening activists with devising systemic solutions for unwilling bureaucrats without offending or alienating them in the process.

Victory—as it often is within social movements—was tempered by not only Article 156 but also by the reality that, even after a long, exhausting fight, there is still no formula for how to do activism in an authoritarian state.

* * *

June Chua had several phrases she repeated as we lounged on the cushy loveseats of a private counseling room. The founder and executive director of The T Project—Singapore’s first and only homeless shelter for the transgender community and people living with HIV (PLHIV)—continually apologized for her ADHD and told me to “keep asking her questions. Otherwise, I’ll just keep rambling.”

And indeed, Chua was a force of nature. Her perfectly trimmed bangs bounced in rhythm as she gesticulated, ripping story after story of the various people who have been helped in her shelter.

At The T Project, Chua and her staff of social workers provide shelter, referrals and health care (including mental health) support to their clients. With her 15 shelter residents, she adopts a deeply familial kind of “tough love”; she refuses to coddle them, believing that with food and shelter, each trans person is strong enough to walk down a “homelessness to homeownership” pathway on their own. Chua cofounded the shelter with her late sister in 2014 to help her chosen family: fellow transgender sex workers retiring from their storied careers but therefore no longer able to afford rent. Over the last 10 years, the shelter has grown to welcome transmasculine and younger folks. While Chua takes great pride in the fact that The T Project is a “trans-led, trans-focused, trans-specific” organization, she also expressed hope that until The T Project becomes redundant, it can serve as a safe haven for the LGBTQ+ community at large.

I was curious about how Chua funded her work, especially given the cost of real estate in Singapore. While much of the organization’s early funding was crowdsourced, Chua proudly proclaimed that The T Project currently receives subsidies from the government and has been visited by four government ministers to date. The organization also runs paid sensitivity training for multinational corporations in Singapore—a funding source that the Home Affairs Ministry has barred Pink Dot and other LGBTQ+ organizations from accessing. “We all wish that we could have that kind of sustainable funding too,” one activist said to me when I mentioned that I was on my way to meet June.

When I asked Chua if the government money comes with any obligations or conditions, she scrunched her face, shook her limp wrists and pronounced her second catchphrase of our conversation: “I am not some grand activist or scholar.”

For Chua, The T Project’s outcomes are the survival and social integration of each individual shelter resident. She continuously distinguished the urgency of her work from the ensnarement of monitoring, evaluation and research that NGO workers and scholars know well. Indeed, at any mention of data or research, she shook her head and body in a dramatized allergic reaction.

“I make sure people are still alive to reap the benefits of other people’s activism,” she said.

Singapore’s policies toward its transgender community are, to me, rather surprising. After all, in 1973, it became the first Asian country to legalize gender confirmation surgery and allow gender changes (following surgery) on ID cards. The T Project is one of a few LGBTQ+ and trans-specific shelters to exist, let alone receive government funding, across Asia.

Of course, these advances have hard limits. Surgery comes at an exceedingly high financial, physical and psychological cost, with no trans-specific medical institutions in Singapore. Shelters serve more as a social service stopgap, placing the problem out of the sight of average Singaporeans, than as a way to address transgender people and PLHIV’s susceptibility to homelessness. In a survey conducted by National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, charity Transbefrienders and TransgenderSG, that was released in February, 65 percent of transgender respondents reported harassment and verbal abuse in their workplaces.

As I left Chua’s office, I felt torn. On one hand, shelters serve as a social service stopgap that does not address transgender people’s susceptibility to homelessness. And Chua’s respectful aversion to the work of activists and policy advocates cleaved any systemic approach to supporting her residents.

But maybe that is the cost of survival. When survival is not guaranteed by any other social institution, The T Project undeniably has material and symbolic importance for the LGBTQ+ community. When transgender people have nowhere and no one else to turn to for trans-specific and trans-led services, this is the sacrifice one must make for the movement.

* * *

“Monogamy is dead,” at least three gay men separately told me in facetious exasperation.

At a Japanese restaurant in another one of Singapore’s nondescript malls, a man lamented that no one commits to a monogamous relationship anymore. If you aren’t already in a long-term relationship, non-monogamy—with blurry, even porous lines between polyamory, open relationships, throuples and beyond—has become the relationship status of choice on dating apps in a gay scene organized around nightlife and dance parties.

“Every gay man has probably hooked up with all of his friends—it’s just that small,” a gay doctor in his late 30s told me. In a brunch-forward, health-conscious café fully occupied on a Tuesday afternoon, I recoiled at the claustrophobia of it all, as the man laughingly explained that his best friendships were born from hookups.

Perhaps that is unexceptional in 2025. After all, I have friends all around the world whose marriages began with a Grindr meetup. I’ve hooked up with couples in Taiwan who kept their relationships open from the start, each with iPhone photo albums of the men they’ve slept with. This is our gay subculture.

But in Singapore, “there are no social institutions binding us to any specific type of relationship, let alone monogamy,” a gay public servant in his mid-20s (ironically, in a monogamous relationship) observed. Gay men are without marriage or traditional pathways to family planning, such as surrogacy or adoption. Their partnerships are invisible in the eyes of the state, which allows them to neither live in a BTO flat until they are 35 nor support a partner in medical or legal emergencies. There is no inclusive sexual education or domestic media representation to show them what a gay relationship in Singapore can look like.

“So why invest in one monogamous relationship?” he added.

In a study of long-term gay male relationships in Singapore, the social scientists Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim and Joanna Barlas found that these men coped with broader sociopolitical stressors by focusing on what they could control. They minimized their need for external recognition from their families and the state, making do with the status quo by investing in chosen families and their financial health instead. For single gay men, perhaps the choice to be nonmonogamous is also about “making do”: building a community large enough to cradle them through this utter lack of institutional support.

* * *

The first thing that struck me about Proud Spaces was the electric blue floor: a surprising pop of color that immediately set the space apart from the otherwise nondescript building in a stretch of towering car dealerships.

Then, it was the gentle chatter at every stall of the Queer Christmas Market. The LGBTQ+ micropress and bookseller Rainbow Lapis Press, founded by Koh An Ting, set up next to Singaporean and Japanese zine makers. The queer ceramicist Rayn Leow showcased handcrafted wares he made for a charity that supports adults with intellectual disabilities. Little Botany, Fendi Sani’s collection of ornamental plants that grew from a passion project into a full-blown business, showcased cute succulents next to Prout Pride Merch, with their extensive spread of rainbow paraphernalia. It was reminiscent of the many weekend markets on the streets of Taipei’s major business districts, with an assortment of small bites, trinkets and independent artwork. I was surprised when Proud Spaces manager Joanne Chen told me this was the first LGBTQ+ marketplace featuring only queer-owned businesses to be hosted in Singapore.

Proud Spaces officially opened in March 2024 thanks to the financial support of “queer elders who felt it was long overdue for the LGBTQ+ community to have a permanent physical space to call its own,” Chen said. Since then, the space has served as a gathering ground for over 80 LGBTQ+ community groups, including those catering to queer teachers, Muslims and other intersectional identities within the LGBTQ+ umbrella. However, most of the groups are small and run entirely by volunteers who often lack the expertise to organize, fundraise or handle legal issues.

These smaller organizations also face challenges registering as societies or companies. Heckin’ Unicorn noted that as of 2023, only one LGBTQ-focused organization—Oogachaga, which provides mental health and peer counseling services—has attained charity status and tax exemption. Its registration on the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth’s charity portal, however, is intentionally devoid of any mention of LGBTQ+ identities.

Building capacity and fostering mutual assistance between LGBTQ+ community groups is another of Proud Spaces’ objectives. In addition to providing an affordable, accessible space to meet, it hosts programming aimed at building these groups’ networks and ability to navigate difficulties such as non-profit registration. Since its opening, it has hosted over 100 open and closed events, ranging from the Queer Christmas Market and trivia nights to panels and open mics to volunteer fairs and networking sessions for non-profit workers.

“Being able to congregate in one spot is something non‐LGBTQ+ Singaporeans take for granted,” executive committee member and producer Harris Zaidi told FEMALE.

“Proud Spaces is important because it shows our community that we can help ourselves.”

Beyond the walls of Proud Spaces, in the wake of Section 377A’s repeal, the LGBTQ+ movement as a whole entered a moment of transition. Activists began to reorganize and take stock of what else has been long overdue to ensure the movement’s sustainability.

In addition to hosting its annual gathering in June aimed at building LGBTQ+ support in the general public, Pink Dot has added more internal structure and prioritized increasing its research capacity, producing surveys and policy recommendations to bring directly to its meetings with governmental stakeholders. “Pink Dot is the government’s bellwether of the community’s reaction,” Zaidi said, adding that the organization had a handful of engagements with the government last year.

Within and beyond Pink Dot, some experienced activists have stepped away from the movement to tend to their own financial and emotional scars. On the other hand, the aforementioned outburst of volunteer-run organizations infused the LGBTQ+ movement with new energy and trepidations about longevity. Last year, Tan and the executive director of the sex worker advocacy organization Project X, Vanessa Ho, co-organized quarterly “network meetings,” where LGBTQ+ advocacy organizations convened to provide updates on their work and align the LGBTQ+ movement’s priorities. Topics of conversation included: Is Singapore ready for a marriage equality campaign? What do queer-affirming mental health services look like? What are some best practices for bringing new energy and volunteers into the movement?

Tan said that while it was energizing to see new faces, even in last year’s network meetings, participation had begun to fluctuate. Newcomers eventually reach a point when they realize that to be an LGBTQ+ activist in Singapore is to contend with an utter lack of funding and civic structure.

Despite those struggles and growing pains, however, an undeniable warmth still radiated from the pockets of the queer community I encountered in Singapore. At the Queer Christmas Market, vendors guided me to their friends in the room as I rotated in and out of circles of conversation throughout the afternoon. I listened as Koh recommended queer books of poetry and fiction to familiar friends, as Leow introduced the details in each of his ceramic creations, as Sing! Men’s Chorus briefly commanded the room with holiday carols.

“I’ve learned that I don’t have to set myself on fire to keep others warm,” Tan replied when I asked how he’s taken care of himself during his time in the movement. In the long shadows of the Singaporean state, I found little fires everywhere, once flickering with the uncertainty of survival, now gathering embers to last.

Top photo: Pink Dot 16 at Hong Lim Park (Instagram: Pink Dot SG @pinkdotsg)