LISBON — I sat on the bed only to discover a wooden slab under the thin, grey sheet. The naked bulb illuminated claustrophobia-inducing walls bereft of windows. The harsh ring of the hallway rotary dial phone pierced the silence.

Thankfully, there was no prison guard to pick it up. I walked out of the cell a free man from where others had been taken in handcuffs, the same ring signaling their summons to the torture chambers.

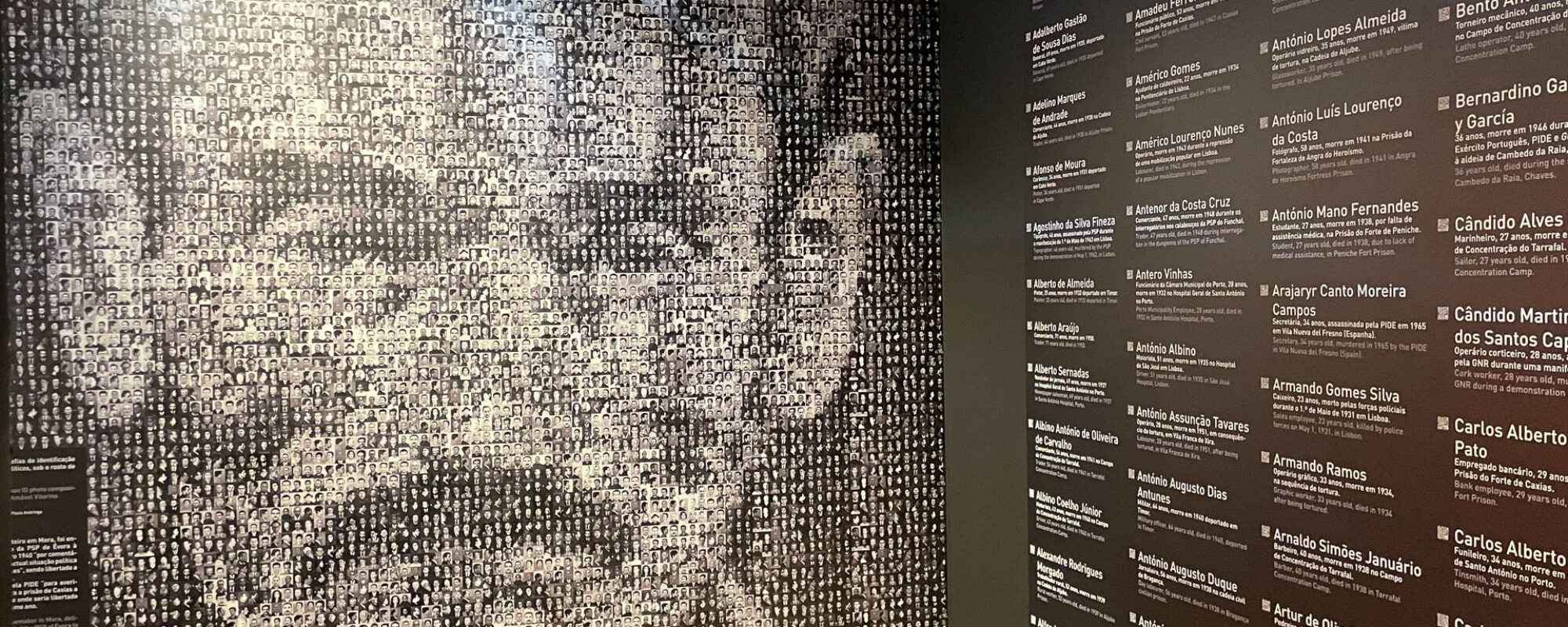

The solitary confinement unit in what is now the small Aljube Museum in downtown Lisbon stands across the street from the imposing Cathedral of Lisbon, the former prison and nearby church poignant symbols of Portugal’s 48-year dictatorship that ended in 1974. While the revolution five decades ago and subsequent transition to democracy are presented today as relatively peaceful, scratching the surface of official history reveals a more sordid tale that lives on among many Portuguese today.

Scientists have well documented how stress leads to increased substance use. Heroin in particular seems to find a foothold in communities in which people feel displaced and abandoned. The heroin crisis that engulfed every Portuguese neighborhood soon after the revolution was no exception. It’s worth exploring that past to place the explosion of heroin use and the drug reforms that later ended it within their historical and cultural context.

The Portuguese dictatorship, led primarily by Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, started with a coup d’etat in May 1926 that replaced a short-lived republic that had in turn ended the Portuguese monarchy in 1910. Initially drawing inspiration from Hitler and Mussolini, the new regime stayed neutral during World War II given its long-standing alliance with the United Kingdom. As the Allied fight against fascism turned to a struggle against communism, Western powers saw Salazar’s state, called Estado Novo, as a bulwark against the communist influence west of the Iron Curtain.

While Salazar’s regime proved effective against communist elements at home, it was disastrous for the Portuguese people. In the Estado Novo’s last years, infant mortality hovered around 38 percent and illiteracy at 25 percent. Only 47 percent of Portuguese enjoyed tap water in their homes, 63 percent had electricity, and GDP per capita was 30 percent less than in neighboring Spain and less than half of France’s. Trade unions were banned and children worked in factories.

“It was horrible,” says Rodrigo Coutinho, a doctor who is clinical director of the Ares de Pinhal non-profit—which provides harm reduction and treatment services for people who use drugs—and was at university back then. During those hard times, alcohol was the intoxicating substance of choice. Regime propaganda advertised “drinking wine provides food for one million Portuguese.” 50 years later, one in five Portuguese still drink alcohol daily. Heroin, on the other hand, was consumed only in small groups of mainly upper-class socialites and artists.

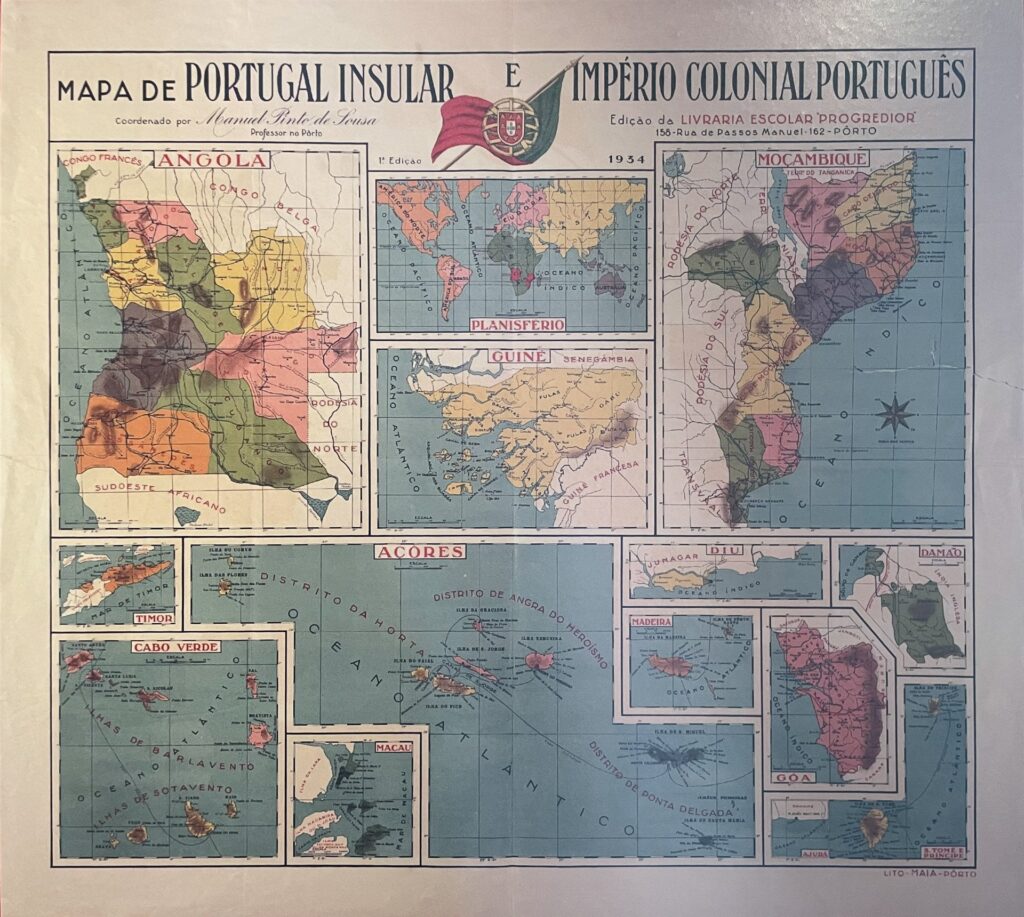

But developments on the mainland only partly explain the troubles facing the country. You may remember from history class that Portugal launched the European age of discovery and colonization in the 15th century but may not know it was also among the last to give up its colonial possessions—Macau in 1999.

Unapologetic about the country’s colonial history and proud of those lands it still held, the Estado Novo fought tooth and nail to preserve the empire stretching from the Minho River on Portugal’s northern border to East Timor in the Asia-Pacific with Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique among others in between. The Portuguese mainland accounted for only 4 percent of the empire’s global footprint.

As the winds of independence swept through the African colonies in 1961, the Estado Novo fought fiercely to maintain control. The regime would eventually draft over a million Portuguese from the mainland to fight for continued control of its colonies over the course of 13 years of war. With few exceptions, men were mobilized for service that included two of years fighting in the African colonies. Another half-million were recruited from among white colonists and local sympathizers.

As disillusionment with the regime and its colonial jungle wars grew, so did substance use. João Goulão, current head of Portugal’s drug agency ICAD, who was not drafted because of his medical studies, points out that whiskey in the colonies could be cheaper than water, cannabis was prevalent and many young soldiers began using heroin during their deployment.

War fatigue helps explains why it was the armed forces who overthrew the unpopular regime on April 25,1974, when only five people died. With their platform of “democracy, development and decolonization,” Portugal’s new political leaders—including Francisco da Costa Gomez, head of the Provisional Government of the Revolutionary Council—negotiated swift independence for the colonies, most of which achieved sovereignty by the end of 1975.

Fleeing retribution, more than half-a-million “retornados” consisting of colonists and sympathizers fled to the mainland. Some came from families that had never set foot in Portugal for generations, many lost everything and all returned to a hostile climate. Along with them came retreating troops from their jungle outposts.

Hugo Faria, general coordinator at the Ares Do Pinhal non-profit, remembers smoking pot with his friends as teenagers in the ’80s. “We were just fooling around being kids,” he told me. One day playing soccer, one of his friends kicked a ball into an adjacent lot. A neighborhood boy playing with them asked Hugo to hold a plastic bag he’d been carrying in his pocket. After the boy jumped the fence, a curious Hugo looked inside to see a couple needles and white powder.

Not long afterward, Hugo’s friends returned from their usual cannabis-buying expedition saying dealers no longer sold marijuana, only heroin. Their experience was not unique. Multiple people I’ve spoken with corroborate that for a time in the early 1980s, drug dealers abruptly switched to selling only heroin for reasons that remain unclear. (It’s notable that the fear of such a bait-and-switch in the Netherlands prompted the Dutch government to sanction cannabis coffeeshops in the 1970s in order to segment the drug market.)

Portugal’s accession to the European Union in 1986 may have worsened the problem as the Turkish Mafia began using the country as a conduit to transport heroin to the continent.

Many of Hugo’s friends shied away from trying the new injectable substance, about which no one knew anything, but a few tried it. Ever since, he’s tried to understand what made some take the fateful choice. Heroin, locally dubbed cavalo (horse), took an unwitting Portugal for a lethal ride. Soon, Hugo was hearing stories from his parents about so-and-so who’d robbed a family member or begun acting out in weird ways. Within the span of a couple years, Hugo began seeing people addicted to heroin on the streets. A neighbor, a former classmate—some alive, some dead.

By the 1990s, a full 1 percent of the population is reported to have been addicted to heroin, cutting across all levels of society from the justice minister’s daughter on down. Everyone knew a family member or someone from school, church or neighborhood who had been affected. The situation was relatively worse than that in the United States today, when 0.75 percent of the population was diagnosed with opioid use disorder in 2021. In comparison, at the height of the Dutch heroin crisis, it’s estimated only 0.24 percent of the population was using heroin.

Just as puncture wounds festered on the bodies of those who injected drugs, societal lesions broke out in cities across Portugal, the historically blue-collar Casal Ventoso neighborhood of western Lisbon being the largest example. At its peak, it attracted over 5,000 buyers a day and had the dubious honor of becoming Europe’s largest open-air drug market. Harm reduction techniques like syringe exchange programs had not yet arrived and people who injected drugs would “clean” their needles in communal water bowls filled with lemons and limes, only accelerating the spread of bloodborne diseases.

By the end of the 1990s, infection rates among Portuguese who injected drugs were astronomical: 80 percent tested positive for Hepatitis C and 60 percent for HIV, with 350 fatal overdoses a year. Tuberculosis rose as high as 14 percent among those frequenting Casal Ventosa. Astonishingly, 2.5 percent of Portuguese teenagers aged 16-18 admitted to using heroin, and 90 percent of people had never accessed treatment. The latter figure is less surprising if no less concerning when I realized that nearly 90 percent of Americans with opioid use disorder to do not have access to evidence-based, medication-assisted treatment.

“People lost arms and legs because of gangrene and other injection related diseases,” said Américo Nave—executive director of Crescer, a non-profit serving people who use drugs—reflecting distantly, seemingly unable to believe he had seen the cause of such despair with his own eyes.

How did matters get so out of hand? It turns out that a societal culture conditioned by repression is much more difficult to shed than an authoritarian regime.

The Estado Novo surveilled all aspects of citizens’ lives for 48 years. It was particularly attentive to any activity the authorities believed could disrupt the social order they mercilessly enforced and assiduously projected to the world. In his book on Portuguese drug policy, Lúcia Nunes Dias writes that under the dictatorship, drugs were viewed as an external threat to society “as if it were a national exorcism, while the real and alarming existence of problems were forgotten.” The totalitarian regime strictly controlled access to information, meaning the average Portuguese had limited general knowledge about the outside world, let alone about illicit drugs.

“The Portuguese default is to be moralistic,” Rita Jorge ruefully joked. “Like crabs in a water tank, if one tries to escape, the others will pull it down.” I met Rita in to discuss her work on international drug policy. However, it was her experience growing up as a child of the revolution that turned out to be most relevant for our discussion. Growing up in the shadow of April 25, Rita remembers the Catholic Church continuing to play a strong role in society. A devout Catholic, Salazar promoted the Holy See’s role setting moral education outside the political sphere in return for the Pope’s blessing.

It’s unclear how big a role the Church played in government affairs after the revolution. However, its sway with the general population as a stable presence amid societal upheaval should not be underestimated. Until the turn of the millennium, 95 percent of Portuguese identified as Roman Catholic, a third attended Mass weekly and an additional 15 percent attended church monthly. Today, Portugal remains one of the most religious countries in Europe, with 75 percent counting themselves Catholic with around 15 percent admitting to being atheist or agnostic. On the polar opposite end of the spectrum are the Dutch, with 48 percent describing themselves as atheist or agnostic.

While it’s not universally true, religious perspectives tend to view the use of intoxicating substances from alcohol to heroin as immoral and the only appropriate remedy is total abstinence. The dioceses of Portugal’s Catholic Church were no exception. Because of that perspective, education and assistance that could have reduced or prevented harmful effects associated with drug use were deemed counter-productive for changing habits. While the theory would later be disproved following the national drug reforms, it meant people who used drugs, their families and citizens at large were left uneducated not just about harm reduction and non-abstinence models of recovery but also about the substantial differences between substances like heroin and cannabis.

Rita also helped me understand how hierarchical and stratified a society Portugal’s is. The Estado Novo and Church are obvious examples of rigid structures, but the divisions cut across Portuguese culture. Just as Salazar was patriarch of the empire, relying on the secret police as one of the state’s repressive organs, so the father was the master of his home where women’s rights derived from their male spouses, domestic violence was common and corporal punishment accepted practice.

Traditional social conventions did not immediately recede with the fall of the regime—even for those too young to have lived through it. In a particularly telling memory, Rita remembers being shocked by her English PhD adviser asking her to debate him on a point she’d made in her thesis while studying in London. In Portuguese classrooms, the professor is the authority and authority is not questioned. The hierarchical culture seems to have allowed little space for the voices of those using drugs, considered the bottom of the societal hierarchy, including those advocating for their needs in meaningful ways through grassroots means.

This pervasive culture of state, religious and familial repression could not but be felt by children. Nuno Maneta, now a peer worker at the Crescer’s drop-in center in Almada near Lisbon, was born in 1972. He used heroin throughout his teens and 20s before going to treatment in 2000 after the reforms at age 28, losing many friends to overdoses along the way. “We never learned how to discuss our feelings,” he said. The revolution upended the lives of a generation without the tools to express their frustrations and vulnerabilities—heroin soothed.

Now in her 40s, Rita feels lucky to have grown up a few years after the main heroin wave decimated the ranks of her older classmates. “We didn’t have someone with a problem in my family but we were the exception,” she told me. She remembers Lisbon’s streets overrun by people using and selling drugs, prostitutes in broad daylight and people sleeping on sidewalks at all hours of the day and night. Wincing at her own recollection, she recalls that many heroin users during the crises were nicknamed carocho—a term evoking a cockroach.

However, as in Hugo’s neighborhood, people who fell into the grip of heroin were not insects but friends and family members. When the topic of my research came up in my Portuguese language class, my professor’s cheery eyes suddenly looked distant. Of a dozen boys who used to play soccer with him in middle school, he told me, only three are alive today. The remaining nine died of overdoses or blood-borne diseases from heroin use.

Born in 1975, he remembers the discolored square on his classroom’s wall where Salazar’s picture used to hang. Salazar and his regime might have been deposed but their imprint on society remained.

Given history’s context, it’s no surprise it was first and foremost religious organizations and the Justice Ministry that were able to start the first centers to help those struggling with heroin. They were focused solely on abstinence. Based in moralistic rather than evidence-based approaches, the well-meaning interventions did little to curb the rise of heroin use.

“It was the Wild West of treatment,” Goulão said. Only in 1997 did the government promulgate comprehensive regulation to enable non-state-run treatment centers, including those with evidence-based, multi-disciplinary team—to get a license, advertise as health facilities and be reimbursed by the state health care system.

In 1987, the Health Ministry established its first treatment center in Lisbon, the Centro Intregado das Taipas. Rodrigo Coutinho remembers opening day. “We were overwhelmed by demand from day one, we knew the situation was bad but never imagined it was as bad as it was,” the doctor said. To meet demand, the Health Ministry subsequently inaugurated 16 satellite centers across the country within a few years.

By 1998, Portuguese were clamoring for a solution that would treat their families and bring peace back to the streets. Goulão, then in charge of the national network of treatment centers, was asked by then-Prime Minister Antonio Guterres—the current UN secretary general—to join the nine-member Commission for the National Strategy to Fight Drugs.

The heroin epidemic was the number-one concern for voters, and the commission was given the broad mandate to solve the heroin crisis. The only requirement from the prime minister was that the recommendations must align with international law.

Within a year, the commission published a report covering 12 areas ranging from treatment, prevention, harm reduction, decriminalization and social re-integration to community engagement. The following year, 1999, the government’s Council of Ministers unanimously approved implementing the recommendations.

But only parliament could decriminalize drug possession. After a vigorous debate, it voted by an overwhelming majority in 2000 to decriminalize drug possession and create the drug dissuasion commissions, which I investigated in my last dispatch. Many right-leaning politicians voted against decriminalization, standing by the traditional tough-on-crime approach. However, when their parties won power in the following 2002 parliamentary elections, the model had already proved too effective and popular to undo.

For Goulão, the foundational message behind the commission’s recommendations was to fight the disease, not people, under his slogan “Better to Treat than Punish. Better to Prevent than Treat.” The change was backed by dramatic increases in funding for prevention in schools, harm reduction (street outreach teams, low threshold methadone, needle exchanges), in patient and out-patient treatment facilities and rehabilitation programs to help people re-integrate into society. “Decriminalization without these investments would be useless or even counterproductive,” Coutinho said.

Within a decade, the number of heroin users dropped from 1 percent of the population to 0.3 percent. Overdoses were cut by more to almost a fifth, from 350 a year to 74. New HIV cases in people who used drugs went from 1798 cases in 1999 to 17 cases in 2021. But just as I found in the Netherlands, it’s not just the people who use drugs and their families who have benefitted, it was the entire community. Lisbon and other cities soon rediscovered their downtowns, opening thriving shops and restaurants. Portugal is now ranked the world’s 7th safest country.

There’s clearly much more to learn about how the national commission’s recommendations and reforms have played out in practice over the subsequent 20 years. At the same time, investigating the cultural and historic roots of the Portuguese heroin crises raises questions about why the drug crisis in the United States has become so horrendous.

How do people feel and experience Portugal’s pioneering drug model today? Were the Portuguese able to shed their cultural morality around drug use? How adaptable is their model to the newer rise of crack cocaine and synthetic drug use? I can now venture into such investigations clear-eyed about the culture and firmly grounded in the history that helped shape both the crisis and subsequent reforms.

Top photo: Wall of remembrance for those imprisoned by the Estado Novo’s secret police, Aljube Resistance and Freedom Museum