PORTO — Sip, breathe in through your teeth, swirl and swallow. Hints of vanilla. Or so I’m supposed to taste according to our bubbly winery tour guide. I nod along while my unrefined palate perceives only fermented grapes. Our guide explains that this red is best paired with red meats of Alentejo—Portugal’s southern region best known for its delicious cuisine. The wine goes down easy even though it’s before noon. I’m told anything under 13 percent alcohol by volume (abv) is considered water in the Douro Valley.

As we finish the tour, our guide jokes that her father’s key to avoiding hangovers was to never stop drinking. The group chuckles. Another sip. I wonder what reaction she would receive if her father had favored another intoxicating substance. Another swallow. Why is copious consumption of alcohol socially accepted while even small quantities of other substances are deemed unquestionably problematic?

Four months ago, I came to Portugal to research illicit intoxicating substances and the legal and cultural frameworks that surround them. But what has shocked me most is the voluminous quantity of alcohol imbibed by the average local. One in five people drinks every day, more than double the European average. I’d be impressed if I weren’t so alarmed.

During my first weeks in Portugal living in Lisbon near central Marques de Pombal Park, I’d run into a mini market, usually run by a middle-aged south Asian man, with shelves stacked with beer or wine for under five euros, every few blocks. The one next to my house had regulars outside drinking as early as 10:00 a.m. with a rotating cast until it closed around midnight.

But let us not judge these men—they were almost always men—too harshly. For further down the street at the first Portuguese restaurant would be another group of locals, men and women, enjoying their mid-day beer or wine of choice. The only differences between these groups were the cost of their drink and subjective stature in society—no small difference when passing judgement, as Friedrich Nietzsche reminds in On the Genealogy of Morals.

The Portuguese are particularly in love with wine and can boast drinking the most in the world with 51.9 liters per person per year. Soundly beating the Italians and the French with 46.6 and 46, respectively, and dwarfing Americans’ consumption of 12.2 liters per person.

Francisco, a young local man in his 20s I met during the winery tour explained that drinking wine for his family is as foundational to being Portuguese as sanctifying Cristiano Ronaldo. His grandfather would drink vinho verde, local green wine produced outside Porto with 10 to 11 percent abv, in the morning. Another Portuguese favorite is Bica com Pinga espresso with a splash of local firewater.

His parents were more modest in their consumption but never missed a glass of wine at lunch and dinner. One wonders if that kind of daily consumption may have any causal impact on the fact that Portugal happens to be a country where workers clock in some of the longest hours while simultaneously being some of the most unproductive in Europe (ranked 9th from bottom).

For his part, Francisco remembers college parties where the go-to drink was port, which at 19 to 22 percent abv, with added sugar, can make a lasting impression the next morning. Now a working professional, he keeps his drinking to an evening beer or wine with dinner at most.

The ubiquity of alcohol, especially wine, in modern Portuguese society is no cultural happenstance. The generational divide aligns with the various government regulations of the times. Under Portugal’s pre-1974 Estado Novo dictatorship, the wine industry was supported by the state, with a mandate of quantity over quality. Over-production led to coordinated campaigns between the government and industry to get the Portuguese to drink more wine. A famous propaganda slogan of the time encapsulating the drive declared: “Drinking wine is like giving bread to 1 million Portuguese.”

There seems to have been no national minimum age requirement for alcohol during the dictatorship. A manifesto by the Wine Merchants Guild of the time argued that expanding the consumer base to women and children at every meal would reduce vineyards’ storage problems. It was not until 1993 that Portugal established a legal drinking age of 16 years old. It took another 20 years to raise it to 18.

But the proselytizing of wine by government officials transcends political eras and philosophy. In today’s democracy, José Manuel Fernandes, the minister of agriculture and fisheries, declared in October 2024 that “longevity is greater where they drink green wine.”

It should come as no surprise therefore that the alcohol industry continues to be a key stakeholder at the table of Portugal’s national taskforce responsible for overseeing the industry and ensuring public health safeguards with regard to drinking. One official privy to the inner workings of the taskforce, who did not want to be named, bemoaned that each time the group looks to curb alcohol use or launch an awareness campaign with such measures as raising the drinking age, adding warning labels or creating stricter sale requirements, the main beverage producers warn that such moves would lower tax revenues.

And so little gets done. The cozy arrangement ensures lax requirements for acquiring liquor licenses, that alcohol companies are in the room when public health officials make public education campaigns, and alcohol is readily available on every street corner.

The same official explained how in the nightlife areas of Lisbon, kids of 13 or 14 go out drinking in groups until 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning with many arriving at the hospital in need of emergency care due to overconsumption. “The scary part is that it’s the parents who usually drive them there,” she told me. Parents don’t think twice about teenagers coming home drunk, but a whiff of cannabis or another drug can bring swift punishment.

Why is that?

Perhaps the simplest explanation is that the Portuguese have had generations to understand wine and its induced behavior change, unlike with other intoxicating substances. The first grapes were planted here by the Phoenicians in the 4th century BCE. Large-scale viticulture took off thanks to the Romans in the 1st century BCE. Today, there are close to 18,000 farms producing grapes and as of 2001, the Douro Valley has been a UNESCO World Heritage site.

When I told a local friend about the topic of this dispatch, she said she had a hard time imagining northern Portugal without wine production. “It bonds the fabric of our communities,” she explained. In her village outside Porto, it’s common for families of all classes to have wine cellars. Her family’s garden includes grape vines and during the autumn it’s customary for neighbors to come together to harvest the grapes at each house before joining large community dinners where the fermented grapes of previous harvests buoy the mood.

Moreover, while agriculture in northern Portugal accounts for only 2.6 percent of the region’s employment, the bigger impact comes from wine’s attraction for tourists, which in turn has led to a boom for service sector jobs in hotels, restaurants, shops and for local artists. In 2019, Porto had 3.7 million visitors while its permanent population hovers around 230,000. In a tale that reminds me of my hometown of Portland, Maine, what the Tripeiros (people from Porto) gained in employment and gentrification, they’ve lost in housing as rents and homelessness skyrocket.

As my friend and I talked, we were walking through Villa De Gaia, on the other side of the river from Porto, where the names of the region’s largest wine houses pepper the skyline like those of Swiss watchmakers in Geneva. The centerpiece is the World of Wine “cultural district” encompassing six museums, seven restaurants, a wine school and weekly events. Its new construction and sleek exhibits left me almost believing that drinking more wine would make me a better friend, brother and lover living a happier life.

Unfortunately, the ubiquity of alcohol in Portugal and its historic roots does not negate its qualities as a risky intoxicating substance. The reality is starkly different. There is no safe level of alcohol consumption, according to the US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. It is the leading preventable cause of cancer in the United States and globally. Both the US Surgeon General and United Nations World Health Organization recommend placing cancer warning labels on alcohol bottles, but so far only South Korea and Ireland have attempted to do so.

In 2010, the esteemed British medical journal The Lancet ranked alcohol the most harmful drug with a score of 72 out of a maximum 100, while heroin and crack cocaine came in with a score of 55 and 54, respectively. That’s because while alcohol is less harmful to users than the other two at an individual level, it was found that the harm caused to those close to people drinking alcohol tends to be far higher—with marked increases in domestic violence and traffic accidents, for example.

Moreover, alcohol was found to be the leading “gateway drug” for teenagers leading to experimentation with other licit and illicit substances, according to the American School Health Association. Leading researchers say alcohol should the primary focus in school-based prevention programs.

It’s also worth remembering that before heroin “junkies” and crack cocaine “fiends” entered the public imagination, there were and continue to be “winos”—please forgive my use of non-first-person terminology. The reality is that the other drugs have not replaced alcohol, they’re simply added on top of alcohol use. For many NGO workers who assist people living on the street, alcohol-related behavior is the most difficult to engage with.

Most people who have alcohol-related problems are our friends, family members, colleagues and acquaintances. Which begs the question: What actually is addiction, abuse, misuse, dependency, use disorder, problematic, chaotic or the other myriad names we use to label behavior with which we are uncomfortable—and who gets to decide?

While 20 percent of Portuguese drink every day and Portugal is ranked 20th globally in alcohol consumption per capita, they supposedly only have a 4.2 percent alcohol dependency rate. On the other hand, only 5 percent of Americans drink every day and the United States is ranked 35th in the world for alcohol consumption per capita, but it’s estimated our alcohol dependency rate is 10 percent. Which begs the question of how local cultural perspectives play into clinicians’ and society’s views about what constitutes abuse and what doesn’t.

When I attended the Lisbon Addictions conference in October 2024, I asked many of my fellow participants to describe substance use disorder and who gets to decide who has it. The most common reply was an eye roll. The second-most common was the tried and true: Substance abuse is the compulsive use of a substance despite adverse consequences.

Unsatisfied, I repeated: What’s considered adverse and who gets to decide for whom? If drinking any level of alcohol can lead to short-term and long-term adverse outcomes for the people using and those around them, why don’t we consider any use problematic?

When I posed the question to my local Porto friend, she explained that while drinking daily is not seen as abnormal, acting unseemly or obviously being drunk is considered inappropriate.

But what if one were to have grown up in a country with nonexistent or strictly limited alcohol use? Places like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Malaysia, for example, or Indonesia, where alcohol is banned under the Quran because of its risks, and therefore consumption per capita ranges between 0 and 0.7 liters per person per year. Our view of what would account for unseemly or unacceptable behavior under the influence of “low” or “moderate” use would be much different.

Because Portuguese culture, and others from America to Japan, have normalized problems arising from alcohol use such as hangovers, forgetfulness and rudeness, we don’t see them as problematic. We’ve associated abuse with “problematic” behavior, so as long as people behave in ways that are normalized, we don’t consider it abuse or dependent behavior.

As Francisco’s family consumption or American attitudes toward cigarettes demonstrate, what’s considered normal or problematic can change over time and generations. So why do people drink in the first place?

Because for all of alcohol’s harms, let us not forget the benefits drinking can bring people in cultures in which it’s accepted. Above and beyond the suppression of anxiety and insecurity, alcohol can bring a sense of social inclusion and professional success.

In Portugal and across Europe, people have a few beers in town squares not only to be with friends but to feel part of a community. Before I stopped drinking regularly, I could go to any bar in any city in the world and feel a sense of belonging. Furthermore, in cultures as varied as Portugal, Japan, America, South Korea, and Brazil, a lot of professional development and promotion selection happens during drinks after work.

Each milieu has varying expectations of appropriate consumption and behavior, but for those who can fit into the expected mold, there are tangible social and professional benefits even when drinking simultaneously erodes health and other aspects of their life.

If people drink in such a way that makes them successful at work and gives them a sense of belonging among friends but also leads them to be emotionally distant from their families while being detrimental to their health—are they abusing alcohol, and who gets to decide if they need help? They themselves? Their family members? Partners? Friends? Clinicians? The government? How do power dynamics and socio-economic class play into such perceptions?

I don’t know but I believe the answer is as amorphous and contextual as the culture in which it’s diagnosed.

The Portuguese public health approach toward illicit intoxicating substances such as cannabis, cocaine, MDMA and heroin has done a very compelling job answering these questions for people who use those substances through the drug dissuasion commissions I outlined in my first dispatch from Portugal. Trained psychologists and sociologists rate people from high to low risk and suggest various pathways and information depending on the levels.

Tellingly, no such system has been put in place for people stopped by the police for alcohol-related disturbances. While I’ve been told that such proposals have been discussed, they would require legal changes that are for now unlikely.

What might be even more difficult than changing laws is breaking down the cultural barriers between the moral “us” and immoral “them” that separates the users of alcohol from users of other intoxicating substances. Such distinctions may have less to do with morality than power.

While I did not find information for Portugal, data from the United States indicates that alcohol consumption increases when household income and education do, too. Less than 50 percent of people making under $40,000 a year drink alcohol while 80 percent of those earning $100,000 do. The opposite trend is true for cannabis. Which raises questions about how normalized habits of the upper classes influence the political processes surrounding the setting of substance-use policies that are then forced on the rest of society.

The obsession some have with abstinence as a solution to all problematic substance use is a moralistic one. The reality is that even with alcohol, those who attempt detox and abstinence-based programs eventually go back to drinking most of the time. That has led to a growing chorus of research demonstrating that public health interventions to reduce rather than eliminate alcohol consumption must be an important tool for improving life outcomes and reducing harm for individuals and communities struggling with alcohol.

I therefore invite you to empathize with those who use intoxicating substances with which you may not be familiar, recognizing that alcohol drinking norms differ across countries, communities and families; understanding the negative as well as positive effects drinking alcohol can have; and knowing that total abstinence is an unachievable goal for most people with problematic alcohol use.

Many users also face criminalization, stigma and less access to care, but may be just as willing to improve their lives when properly approached, educated and supported. I am talking about our friends and family members, after all.

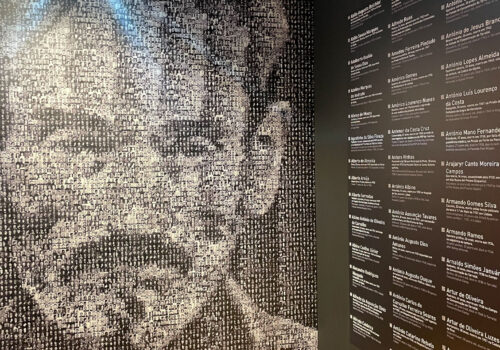

Top photo credit: Daderot, Wikimedia Commons