BOCAS DEL TORO, Panama—We hear the buzz of the motor closing in. Both Josh and I stand up instinctively, peering into the inky blackness for the invisible boat. We’ve just finished eating at our little teak table in the cockpit, enjoying the dark ensconce of the warm, humid evening. I see only reflected yellow lights from town. The whine of the outboard screams toward us, the noise building exponentially. I search the water, confused: the engine is opened up, full throttle. It shouldn’t be coming straight at us, I think, but my ears tell me otherwise.

“JESS, LOOK OUT!” Josh cries and reaches out for me.

Like a ghoul in a nightmare, a massive white bow appears perpendicular to Oleada exactly where I stand. I wave my arms in vain to alert a hidden driver. I let out an angry howl, the kind of primal yell that makes my throat hurt for days.

My yell turns to a scream in the fraction of a second between when the boat materializes and when it collides at full speed with Oleada’s hull. It’s a 25-foot cayuco, the kind of massive, narrow open boat that the native Ngobe people carve out of a single immense tree. It hits like a six-foot-wide redwood slamming into our boat at 20 miles per hour. Oleada barely budges—she takes the hit so well that Josh and I aren’t even knocked off our feet. But our dishes fly off the table as the bow rides up into our lifelines, thin rope stronger than steel that lines the edge of the boat to keep us from falling off, before the cord stretches, then springs the cayuco back into the water, stopping it from launching into our cockpit. The inch-thick steel stanchions securing the lifelines remain bent from the effort to repel the boat as it slides back into the black water.

Josh is still yelling as I stare in amazement at the edge of Oleada, expecting it to be torn in two. The cayuco that just hit us drifts alongside, the motor still chugging. Josh rushes to the side of the boat.

“Amigo! Amigo! Todo bien? Jess, find a light!”

Staring at this inexplicably violent scene in front of me, Josh’s voice breaks my trance and I rush into the cabin and grab our spotlight. It does not dawn on me how lucky I am to be alive. I am mainly worried that we might be taking on massive amounts of water. I drop to my knees amid shards of wood and fiberglass to run a beam of light along the hull. I expect to see water rushing in; surely our boat, our home, is sinking. But at the waterline and almost all the way up to the joint where the deck meets the hull, Oleada remains clean and white, unharmed. I continue to search the hull with the light, expecting catastrophe, until Josh asks me to search the cayuco.

At first, we don’t see anyone in the boat. A bizarre foreboding fills me as I imagine a driverless boat slamming us in the night. But when I spotlight the massive cayuco up to its majestically proud bow, a body lies in the bottom, splayed face down in the rough-hewn wooden hull in the middle, motionless.

The body moans.

I bring our glaring spotlight back to Oleada. A foot-long gash gouges the hull where it meets the deck. The rail and the strip of metal that acts as a track for our jib sheet exploded on the impact, and shards of fiberglass and teak cover the cockpit combing. I lean over the lifelines, still expecting the boat to be filleted open down her hull. But aside from the gash on deck, she appears unscathed.

The driver of the cayuco sits up with a long groan. He’s a young, handsome indigenous Ngobe man. I look up at the top of our mast—our insanely bright anchor light is on. We have a light on in our cockpit, which is far more than most sailboats ever use. Why didn’t this guy see us?

The man struggles to speak with Josh, both in broken Spanish. He tries to start his motor, pulling again and again on the cord until he floods the engine.

“Gas?” he asks us.

The he starts talking about his abuelo. I think he’s trying to identify himself, tell us the name of his grandfather, and I question him eagerly in Spanish, hoping to identify this guy beyond the name he gives us, which is Smith.

“No, Jess,” Josh says quietly. “He’s asking for rum.”

I can’t believe it. Any shred of empathy I have fizzles into the fury brewing in my tense muscles. “You want RUM?!”

“Si si, ron Abuelo.” The driver slurs the name for Panama’s national ron, Abuelo. He sways in his seat in the back of his beautiful cayuco that now has a massive crack running from the proud bow all the way down to the bottom. His boat weighs at least a ton, probably two. The driver, I realize, has no idea what just happened.

“You are drunk,” I seethe in Spanish. “You need to turn your boat around and go back to your pueblo right now.” I then switch to swearing in English.

“Okay, sí, sí, regreso al pueblo,” he murmurs as he drifts away, flooding his engine again as he relies on his reflexes to try to pull the starter cord, wasted and doubtlessly sore. He drifts into the black bay as Josh and I inspect the hole in amazement. I can’t believe this is the only damage aside from the hopelessly warped lifeline stanchions.

Despite the dark, we know we won’t be able to sleep here, and it would be safer to move. I haul up the anchor, and Josh passes me the flashlight. I walk barefoot to the bow to keep watch, still filled with fury.

As I stand on the deck, my hand steady on the wrapped jib in the cool breeze, heaving sobs come over me and bitterness seeps in. I wanted to leave this place months ago, and it only continues to assault us—while making it difficult for us to leave, whether from boat and motor problems, or weather. Now we have a giant hole to repair before we can go anywhere. I wallow in self-pity, choking on my rage.

But my current problems are only a momentary flash compared to the hugely difficult life facing the indigenous Ngobe (pronounced “ÑYAW-bay) people eking out an existence in this tropical paradise. Josh and I would later desperately hope to find a way to help bridge at least some of the divides with a people who have been pushed to the edge of society by 500 years of oppression. But a simple solution doesn’t exist, and our accident had the effect of placing us in the middle of a cultural conflict that would haunt us until we left.

Economic resources from the state are not making it to this far-flung community, despite the tourism boom. The tension—a slew of economics, history, and race—is as palpable as the stench from the sewage-strewn water, but equally undiscussed and untreated.

Back on Oleada, I spotlight the water for answers about the crash. The ocean says nothing, and I scan for nets, hazards, or more unlit boats as we pull into the anchorage on the south side of Isla Colón.

******

When Christopher Columbus visited Bocas del Toro in 1502, he was so enamored with the calm, clear water and vibrant islands that he stuck his name all over the archipelago: Isla Colón (Columbus Island,) Isla Cristobal (Christopher Island,) and Bahía Almirante (Admiral’s Bay).

After Columbus, groups of bandits and prospectors routinely made Bocas their shelter. In the 17th century, pirates used the islands to refurbish damaged timbers on their boats and feast on the many nesting turtles (critically endangered Leatherback turtles still nest here). Although the Spanish did not colonize the area with the same vigor as the gold-laden places of Panama, they nevertheless managed to nearly wipe out the indigenous populations with Old World diseases: when the French Huguenots arrived, Spain sent troops to this remote coast to stake their claim and eliminate the locals.

In the early 1800s, the Spaniards once again arrived by ship, but this time, they brought their slaves from the United States and the Colombian Islands on the Nicaraguan coast. When the slaves were “freed” in 1850, many stayed as subsistence fishers. At the end of the century, blacks from Jamaica arrived to serve the growing banana industry, and the area continued to grow an established Afro-Caribbean community.

The United Fruit Company showed up in 1890 to build a vast banana empire in the islands and the entire peninsula. Old photos from “Bocas town,” the most populous town of the islands on Isla Colón, show beautiful homes—and emerging classes. White managers watched over black and indigenous workers. Today, most of the houses are gone from fire and neglect, and the banana operations are now Chiquita, which employs eighty percent of population on the mainland. The company still maintains this mostly black and indigenous workforce and exports three quarters of a million tons of bananas annually. In a cab on the mainland, my driver gestured out the window, sweeping his hand over the hills: “Puro banano.” The countryside is completely bananas.

We also arrive by ship to Bocas, one much smaller than Columbus’s—not without the uneasy awareness that arrival by sea here evokes 500 years of European ships of conquest and extraction. But we arrived in Bocas del Toro giddy with excitement. Our first populated stop in the Caribbean, this town tucked into an island archipelago is a backpacker stronghold, way off the beaten tourism path. Colorful fiberglass skiffs called pangas serve as public transportation between the islands in Bocas, and a strong surf culture rules the many breaks over the reefs that once hid pirates.

Despite growing tourism, the little towns are unabashedly gritty. Subsistence living has become tougher with more fishers and depleted resources, and the locals grudgingly rely on the short tourism season—for which the government rarely sends resources to support infrastructure or other needs. The town “hospital” is overgrown with weeds. The sewage treatment plant in Bocas was recently overwhelmed by increased inflow. It spills untreated sewage unabated into the island waters, as it has for months.

We carefully follow a narrow channel between reefs and mangroves into a marina on Isla Bastimentos, “Resupply Island.” The marina is part of a sprawling resort of California-style homes perched on a steep hillside facing the Caribbean on the windward side of the narrow island. The main town on the island is a couple miles from the marina and populated almost entirely by members of the Afro-Caribbean community, who commute by panga, squeezed shoulder-to-shoulder into the vessels of varying degrees of disintegration, to work at the resort. In the town, a few hostels and cheap restaurants hang into the water of the protected bay in the lee of the island, faded paint colors over rotting wood.

The marina makes it easier for us to access land and get to know the community. We stayed long enough to see the complexity of shadows thrown by racism and entangling the population, like the hidden but slippery roots covering the jungle floor.

When I asked about walking to the town, both the marina management and dock workers shake their heads. “Take a boat. A few people have been mugged on the trail.” By the time we left, that trail would be site of a brutal murder of a recent Columbia graduate, another hint of the tensions rising between tourists and locals.

I notice another trail leading in the other direction, away from town: a root-choked, narrow path diving into the jungle inconspicuously behind the small general store at the open-air reception for the resort. Only indigenous men, women, and children disappear down this trail. Josh and I often sit near the entrance, waiting to feed stray dogs, noticing that only the Ngobe use this obscured portal.

The Ngobe are an indigenous people of Panama and Costa Rica who were the first to repel Christopher Columbus. They lived in dispersed communities until the Torrijos regime in Panama in the 1970s encouraged more permanent settlements with roads, schools and clinics. Despite their long-nomadic roots, many survive at the bottom of the cash economy, picking coffee and bananas and migrating seasonally with work.

Daily, we walk the dirt road from the lee side of the island over to the rough surf on the Caribbean. We see more sloths here than in all our time in Costa Rica. Most of the locals from Bastimentos consistently greet my smile with a scowl. The Ngobe mostly respond with widened eyes, but over time, we begin to recognize each other and they return shy smiles. On the beach, I become familiar by name with the Ngobe children hawking homemade coconut oil packaged in used liquor bottles.

Almost every morning, we see a man named Niko who walks from the Ngobe community to his job as a laborer at a beach shack that serves overpriced tacos and drinks. At five feet seven inches, I’m at least a foot taller than he. He regards me with approval when I tell him that I collect stories about climate change from locals, and I would love to hear about his life.

“No one has ever, EVER asked me for my story before.” His eyes twinkle and he puffs up his chest.

Niko moved from the mainland with his family twelve years ago when the resort first began construction. They were promised work, housing and running water. A small Ngobe community already lived in the area, but it swelled with the enticement of consistent work.

“There was work then, but only for a little while. Now, not so much work.” Both Niko and I are speaking to each other in Spanish, our second language; his first language is his native Ngobe, still spoken by 250,000 people in this region. As we walk, he points out a sloth, ku in Ngobe, in the top of a tree, the kuru. I never saw him look up to detect the sloth.

When I ask about his family, Niko tells me he is tired from staying up the night before with his daughter’s son. When I see him the next day, he tells me the boy is in the hospital.

“What’s wrong with him?”

“He has a fever and a terrible cough. He couldn’t breathe.”

To take the child to the hospital in the middle of the night, Niko had to find a panga driver awake at 4 am and willing to take the boy and the family from Isla Bastimentos to Isla Colón. They were charged $40 for the trip, which is most of Niko’s income for the month. Not only is it outrageously expensive, the passage at night is dangerous in open boats: they must cross a channel full of reefs and open to the ocean, where swell and wind funnel through. An unexpected wave could have swamped and capsized the little boat. Passengers rarely survive when that happens.

What can we do to help? Do you need medicines? Niko nods eagerly. But he can’t tell me anything more about what the child has, and in his worn brown trousers and rubber boots, he steps into the jungle, machete in hand for a day’s work.

*****

When we walk the road, we pass a dump and scrap pile where the resort heaps its unwanted wares in the forest. The Ngobe often pick through the pile to salvage building materials. A few days later, Josh and I are walking toward the boat when we catch up with a woman carrying a stack of at least twelve eight-foot-long two-by-fours on her shoulder. The road is gravel, and she wears no shoes or sandals, like most of the Ngobe we see.

I have never seen anyone stop to help any Ngobe with any of these loads. I’ve had enough. I jog to catch her.

“Can I help you?” To my surprise, she sets down the planks and nods with a faint smile. Josh and I divide the boards and start back down the road with her. They cut into my shoulder as we walk down the trail to the indigenous community, Bahía Roja.

I have been hesitant to walk the trail myself; I don’t want to invade a community if it doesn’t want outsiders. But this woman leads the way. We step over roots slick with black mud, winding into the jungle until we emerge in a brilliant green field with shin-high mud. Past the field, shacks on stilts ring a sloping green field. Most of the houses sit at the edge of the mangroves in the thick tidal mud.

Carrying the boards, we follow the woman as she slips between a few shacks and into the mangroves. She balances on impossibly narrow poles and slick trees to thread her way through other houses, mud and eventually water to reach her home. I give up trying to balance and trudge through the water, immediately breaking a flip flop and choosing bare feet over potentially slipping off the tenuous path.

When we arrive at her house, an elder teenage son takes the boards without making eye contact, and six girls of various ages giggle at the doorway. The woman invites us inside and pours us each a plastic glass of tepid orange Tang. Josh and I exchange a look, acknowledging that it might be a bad idea, but drink it anyway.

Inside her house, maybe 150 square feet in total, I can peer into the water four feet below through the warped gray floorboards. She has a small table for preparing food and tells us that they brought the boards to make a new, larger table. Josh and I sit in the only two chairs. The back half of the space is divided into two sleeping areas by a sheet. The girls lean against the wall, smiling.

They laugh uncontrollably when they offer to sell us coconut oil, which they do purely in jest, since we are in their home. I’m surprised by their sophisticated sense of humor. I talk to the girls, and the eldest, in her early teens, tells me that she wants to learn to speak English before she attends school in Bocas town. The youngest child, a boy about three years old, scrambles up in to the mangrove tree in front of their house, displaying his climbing prowess.

On a crank-powered radio hanging from the only hook on the wall, which is made of the same boards as the floor, pop music blares in English, and I almost laugh out loud thinking of the contrasting lives of kids listening to this music. It’s such a different life from an American child. Here, six-year-old girls spend their days alone on the beach selling coconut oil to tourists, siblings are responsible for each other and three-year-olds are responsible for themselves—under the eye of the tightly packed community.

When we make our way back through the mud to the central field, I’m emboldened by our interactions, and I ask where I can find Niko’s grandson. At the edge of the grass, I find Niko’s two daughters, Elvira and Elena, and I ask about the sick boy. They invite me into the cool interior of their home, where the boy swings in a hammock, sleeping.

I ask what medicine they have, and the mother, Elena, shows me individually packaged large pills. I don’t recognize the drug, so I ask her more about the boy’s symptoms. Yes, coughing, she says, turning her eyes away. Elvira looks at the mother, then straight at me.

“Tuberculosis,” she says matter-of-factly, with a hint of exasperation for her sister. Elena’s eyes flit nervously to me, and I try not to flinch. I ask if anyone else has the illness, and Elvira replies no. I take a photo of the drugs with my phone and promise to see what I can find out.

Josh and I walk silently back to the manicured gardens around the marina, sinking into the shin-deep mud and sliding on the knotted roots that the Ngobe walk every day.

When I inquire with a local organization, I find out that the boy’s medication treats drug-resistant TB. The child must go to the hospital every week for at least sixteen months to receive it free from the government. When I inform Niko about this necessary schedule, he acts surprised. Over the next month, the child is in and out of the hospital, needing oxygen, and I try to impress upon him how important it is that they continue the medication, even if he seems better. I offer to help him arrange a ride every week, but he tells me that the cost isn’t much. I can’t tell if anyone understands how important it is to continue the drugs—which, at an inch long each, look very challenging to administer to a child under two years old.

*****

When we see Niko in his cayuco, we call him over to the docks and trade stories from the day. On Josh’s birthday, we invite him to tie up his cayuco and join us on our sailboat.

He steps inside, his wide brown feet walking gingerly on the teak and holly floors. I have made a special treat, pizza and rum cake, both of which require the oven and oppressively heat the small cabin, so we step into the cockpit to eat. Niko eats his pizza and cake appreciatively.

“I’ve been here for 12 years. I’ve never been inside a boat in the marina before.”

When he leaves, we ask if he would like to take any of the food with him.

“Two pieces of cake—one for each of my daughters.” He smiles shyly, then admits that he had never had either pizza or cake before.

The next day, Josh and I walk back onto the dock as the heat beats down from the tropical sun. The dock manager, who goes by D.C., a bald and round-bellied man in his fifties from Wisconsin, steps out from his boat and physically intercepts us, his chin lifted imperiously.

“Hey, you guys were hanging out with some Indians, right?” Josh and I nod. “Well, you should stay away from them. They are not good guys.” I’m about to walk away with a smile perfected for avoiding conflict when Josh speaks.

“That’s just racist.” I swivel on my heel in surprise. Josh is one of the calmest people I know, and he usually manages to avoid conflict. But something has accumulated in both of us, thousands of little straws piling up since we arrived: the trail to Bahia Roja, the deadly diseases festering in a community a few hundred yards from an exclusive resort, the way white visitors to our boat are welcomed and brown ones turned away.

The dock manager turns red and sputters retorts and excuses, including that his son-in-law is black, so he couldn’t be racist. Together, Josh and I manage to de-escalate the argument over the next ten minutes, but not without everyone still bristling from the exchange.

Days later, when Niko paddles to the dock looking for us, the black guard patrolling the dock harasses him as the manager comes to find us. D.C. swings his arms wildly while his eyes flash, and he walks towards me menacingly. I manage to duck under his arm and sit down on the dock next to Niko to explain the commotion, while Josh calmly stands up to the manager. Niko sits in his cayuco, his eyes wide as I translate the conversation to Spanish, until I suggest that he leave.

“Those people, the Indians, they can’t be trusted,” D.C. insists. “Even Talman here knows that, and he’s black,” he emphasizes, implying that if someone were black they couldn’t possibly be racist themselves. I don’t bother to point out the 500-year-old hierarchy playing out in the islands, a structure in which everyone has someone to look down on—with the Ngobe at the bottom.

Next, the rant continues to the ways in which the marina and D.C. help Bahía Roja—which turns out to be only in the buying of coffins.

“We do so much for the community. You know how much we do? I buy every coffin when someone there dies. And it’s a lot of coffins.”

My jaw hangs open slightly.

Josh and I know that the resort has done very little for Bahía Roja, including shutting down the restaurant on the water only a hundred yards from the docks. The company never fulfilled a promise to provide housing with electricity and water. A local non-profit finally helped to provide residents with running water to a single tap this year. The resort prides itself on providing electricity for the first time this year from its diesel generators, but only the restaurant is electrified, and rates are impossibly exorbitant for the residents.

*****

That night, I imagine that I can hear one of the dogs I have been feeding barking and crying in Bahía Roja. She is the saddest looking dog from our entire trip. She hangs her head and tail low, every rib is painfully visible, and her hip bones protrude under her skin. Her nipples hang infected from nursing puppies. She is always covered in mud from trekking back and forth along the trail seeking tourist trash to feed herself and her puppies.

When I walk to Bahía Roja to find out what happened to her, I discover that Niko’s wife, Magdalena, has tied her up under their house in the tidal mud with a three-foot piece of rope. The dog balances in the mud on a rotted pallet. She has been tied up for six days without food, drinking brackish water, when I finally find her. The abuse is ghastly.

But I am a visitor and tiptoeing through cultural mires. I walk to Magdalena’s door. She stands up grudgingly from her one piece of “furniture,” her hammock, and insists that she wants the dog to stay around so she will feed her four puppies. But the only way the puppies have survived is because I have been feeding the mother.

I am calm and explain that we will feed the mother and puppies, and Magdalena acquiesces suspiciously. Josh unties the dog and she bolts toward the marina with us. My head swims. I don’t know what to think. There is no good answer. I can’t take the dog, nor can I leave her.

How can people treated so cruelly turn exercise such cruelty over other living creatures? It’s only after spending months away from Bocas that I begin to imagine how Magdalena could sacrifice her animal even as many dogs are treated decently by the Ngobe: she wanted the puppies for her children. Just like basics about disease such as TB aren’t taught in any curriculum or in any accessible local information, many lack even more basic information about animal care, or a culture of care. As hard as it is for me to believe that Magdalena and Niko might not know to feed this dog, I must also imagine a life where the only toys a grandmother can give are puppies. She can afford nothing more, despite a heart that aches to do so. Whenever I bring food and medication for the puppies, time and again, Magdalena looks at me incredulously, like she can’t believe that I continue to care for these creatures. She is grateful, and I am careful to express our care for her grandkids as well. I can only hope that my example influences her or her grandchildren. I don’t know what else to offer.

I see Magdalena walking with two five-gallon buckets filled with plastic containers every day on the road, and I take them and carry them for her up to a hostel in the island’s interior. She makes chicken and rice daily and sells the steaming piles of food to the workers. How much? $4 each.

“How much do you pay to stay in the marina?” she asks me. It’s $500 per month, I tell her, one of the cheapest rates for marinas in the Caribbean. She shakes her head as she waddles next to me in her bare feet. I tell her it doesn’t seem fair that she works so hard for so little.

She laughs and tells me that this isn’t work.

“No, cooking is work,” I insist. She smiles again across our cultural chasm, and I think of Niko struggling to find work for years. Maybe it doesn’t seem like work to Magdalena without a boss abusing her and her grandchildren waiting with puppies at home.

Back in the marina, the manager’s insistence on continuing conflict makes the docks unbearable, so we leave. But we depart with unresolved disquietude, far more unsure of who we can trust than when we arrived. Two months later, the white cayuco reminds me that we are still ensnared in this story.

*****

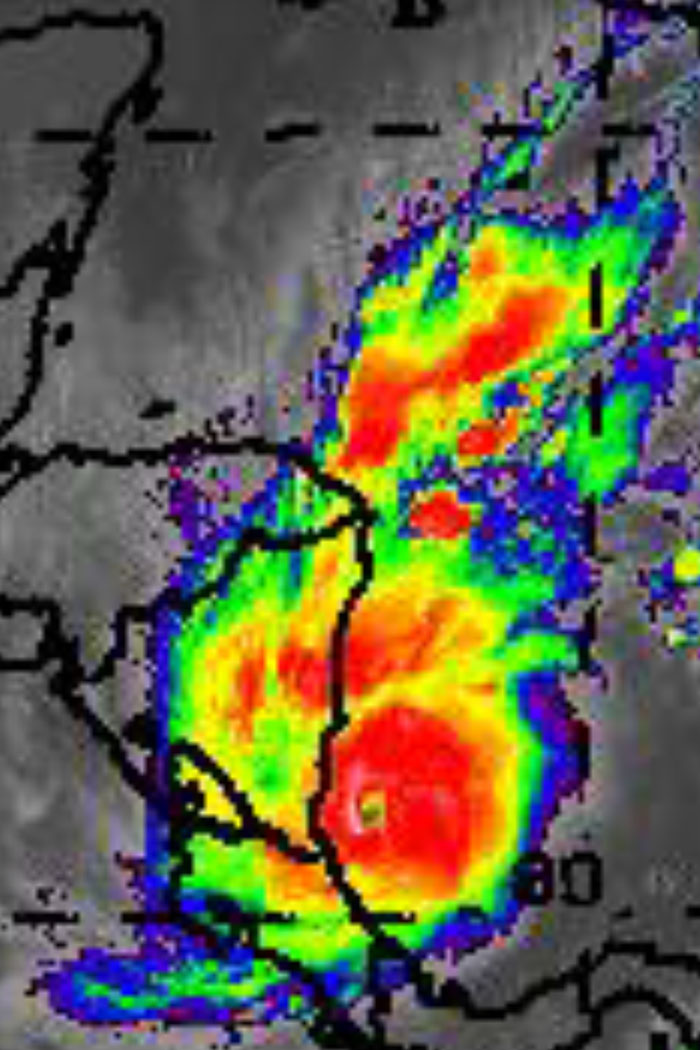

Just after we arrived at Bocas, the southernmost hurricane in recorded history, Hurricane Otto, flooded the city of Colón 150 nautical miles to our east, killing five people (two were schoolchildren), then churned for Bocas. A few people nailed their flimsy corrugated metal roofing with extra nails, a pathetic attempt at security for an event the area was woefully unprepared to experience. As the hurricane spun slowly closer, winds whipped the sea into an angry, frothing mess, and the panga passage from Isla Colón to Bastimentos became prohibitively dangerous.

The hurricane made landfall at the Nicaragua–Costa Rica border. Its strength survived as it rolled over remote and rural coastal towns there. The government of Nicaragua strategically evacuated in advance—an unusually coordinated and lifesaving event. But at least nine people were killed in Costa Rica.

In Bocas, the storm swell carved away the sugary white sand at Red Frog beach and flooded the shacks perched there. That seems like small impacts compared with the inundation and loss of life elsewhere, but the islands completely rely on a short tourist season. Trips were canceled for weeks because of the storm, and reports of ruined beaches filtered out to the wider traveling community. Everyone from panga drivers to restauranteurs complained of a slow season afterward.

On the lee side of the island, Bahía Roja was protected from the storm surge. But nothing protects the Ngobe from insidious poverty and disease. As climate change moves coastal areas like this closer to the direct impact of hurricanes, the poorest communities risk losing even more. Although the Caribbean has proven different from the Pacific, especially in the more overt cultural conflicts, the lesson of climate remains the same: it will be the final straw in communities already struggling on the edge.

A tsunami of literature points to thousands of cases where climate change engenders conflict, whether local, regional or national. Ocean communities remain particularly vulnerable, already depleted with unsustainable fishing practices. Slipping down the poverty ladder, indigenous cultures contribute the least to global emissions, yet frequently bear the brunt of climate impacts because of their close reliance on natural resources. In Bocas, cultural divides create something like a caste system, and conflict over resources already haunts the daily interactions of the separate communities when they come together in the fight for survival.

Yet despite breathtaking racism and the continued struggle for survival, or possibly because of it, the community adapts brilliantly. In fact, it seems to specialize in adaptation while retaining a core value: family. Magdalena may have very little to share with her family, but when I find her at her home, she is often swinging peacefully in her hammock with a grandchild or two in her lap.

*****

Hours after the cayuco hits us, we drop the anchor at the edge of Bocas town, amid water thick with the stench of sewage from an overflowing treatment plant. We both notice that the boat next to us has a patch to hide a gouge similar to ours. These collisions are not uncommon.

In bed in the bow, I lie awake, listening to the panga motors outside our hull as they roar by into the night, flinching as each motor roars near before it passes into the night. A cool breeze rolls out of the open Caribbean Sea, and eventually I slip into a fitful, dreamless sleep.