BERLIN — Before the pandemic, Giulia Silberberger would receive a handful of queries per week asking for help with fact checks or information about various conspiracy theories. The founder of the “Golden Tinfoil Hat,” a nonprofit organization aimed at demystifying and combating disinformation and conspiracy thinking, she and her colleagues have made themselves available to anyone interested since 2014.

But recently, Silberberger and her team in Berlin have noticed a significant uptick in the number of people reaching out. Instead of the usual four or five a week, they’re now getting 20 to 30. What’s more, those calling sound more desperate for help. Most ask for variations on the same thing: Help reaching family members or partners who they say have fallen down a rabbit hole of conspiracy thinking.

The organization has heard from people who want to vaccinate their children against the wishes of their partners. Also those whose marriages or close family relationships are nearly over because of someone’s newfound interest in “anti-corona” protests. And even a wife who found out her husband is involved with the extreme-right Reichsbürger movement only when the police suddenly arrived at their home with a search warrant.

“These are very high-conflict situations,” Silberger told me recently. “Very few want fact checks—that was in the past. Now, all of them just want help, or someone to talk to and a shoulder to cry on.”

She hadn’t planned on becoming an in-demand expert in conspiracy theories. The 40-year-old got the idea for the Golden Tinfoil Hat back in 2014 via a Facebook group where members discussed different conspiracies they’d seen; she joked that she would create an award for the most out-there conspiracy theory, the “golden tinfoil hat.” That’s how the group started: A humorous way to draw attention to what is actually a very serious problem. Its activities, and the size and scope of Silberberger’s team, have grown in the years since: Now, their primary work involves running information sessions aimed at teachers, students and other groups interested in combating the spread of conspiracy theories.

More than just educating about conspiracy thinking and media literacy, Silberberger explains the psychology behind someone’s fall down a rabbit hole. That ability to get inside the heads of those who have fallen victim partly comes from her own biography: She was raised in the Jehovah’s Witnesses and left the sect when she was 26.

“I know how it is when you defend a belief without facts to back it up. It’s not based in facts but in emotions: ‘why don’t you want to believe me,’ ‘you don’t understand me,’ and so on,” she said. “When these people have bound themselves to these conspiracies ideologically and base their entire worldviews on it, it’s difficult to impossible to reach them.”

Nearly a year after the coronavirus hit Europe, Germany—like many countries—has reached a critical point in the pandemic. Vaccinations have been underway for just over a month; although progress feels frustratingly slow, the government says it will offer shots to every resident who wants one by the end of the summer. In the meantime, the country is struggling to get its record-high infection rates down to safe levels: After launching an unsuccessful “lockdown light” in November, Germany has been in a stricter lockdown—with all restaurants, schools, non-essential stores and cultural institutions shuttered—since mid-December.

Even though the case numbers are slowly but steadily declining here, the threat of fast-spreading mutations from the United Kingdom, South Africa and Brazil looms. The government has extended the lockdown until at least mid-February, and Chancellor Angela Merkel has said she expects some form of restrictions to remain in place until Easter. Epidemiologists like the Charité hospital’s Christian Drosten go even further, warning that the country is in for not only a rough winter but a challenging spring and summer as well. People, myself included, are weary and struggling to keep perspective in what feels like an endless, depressing winter.

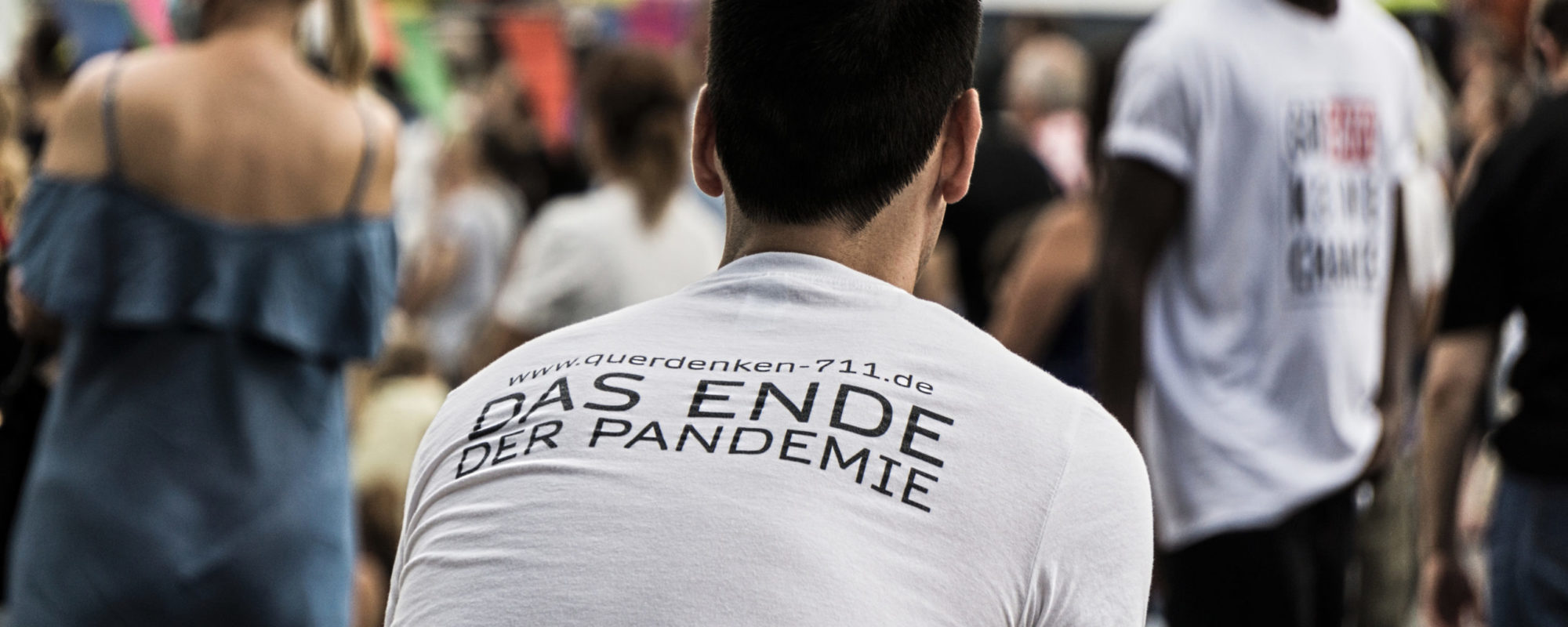

On top of those already complicated dynamics, the spread of disinformation and conspiracy thinking has taken hold at a rapid pace across the country. Spurred primarily by the Querdenken movement, a group founded to oppose the government’s anti-coronavirus measures, conspiracy theories have been given new space to flourish over the course of the pandemic. What started in the spring as a series of small, decentralized protests around the country has grown into an increasingly radical problem.

Founded by a Stuttgart-based entrepreneur named Michael Ballweg, the Querdenker protests have brought together a disparate collection of people. Ballweg’s insistence that everyone and anyone was welcome led to what, at least at the beginning, was a bizarre and hard-to-categorize mix of ideologies and conspiracies.

At the bigger protests this summer, New Age-y anti-vaxxer moms marched alongside neo-Nazis and right-extreme activists. Believers in holistic medicine turned out just as enthusiastically as supporters of QAnon. The highest-profile faces speak to that strange crossover mix of participants: Attila Hildmann is a vegan celebrity chef who has drifted toward the far right; Cecil Egwuatu, or “Coach Cecil,” is a fitness influencer popular on YouTube.

“Not everyone who’s gone to these protests—or at least, not everyone who went to them at the beginning—were believers in conspiracy theories,” Simon Teune, a sociologist at the Technical University Berlin who focuses on protests and social movements, told me by phone. “There are many people who simply said, ‘Something’s not right and I don’t want my personal freedoms to be infringed upon.’” Over time, though, the more casual participants—those who, for example, didn’t feel comfortable marching at the same protests as neo-Nazis—have dropped off, meaning those who are left tend to be more radical, the real true believers. “There’s been a segregation and a hardening,” Teune said.

Whether those who support such beliefs today know it or not, Silberberger said, nearly all conspiracy theories have some kind of basis in right-wing, anti-Semitic ideology. The argument that the government has become an illegitimate “dictatorship” and citizens need to stand up and fight for their rights aligns with the central idea of the right-extreme Reichsbürger, who reject the legitimacy of the modern German state. And even alternative medicine, which is popular among protest-goers, initially grew out of an attempt to circumvent the early 20th-century medical profession in which many Jewish doctors practiced.

“This deeply anti-Semitic and right-wing mindset is present in all conspiracy theories: If you picture them as a house, anti-Semitism is always the roof,” Silberberger said. (“If you think back on our history here in Germany,” she quipped darkly, “you can make your own conclusions and it becomes pretty clear why.”)

This deeply anti-Semitic and right-wing mindset is present in all conspiracy theories: If you picture them as a house, anti-Semitism is always the roof.

Still, the spread of such thinking among the general population here shouldn’t be overstated: The Querdenker movement and others like it, their supporters represent only a small subset of the electorate. Most Germans overwhelmingly support the government’s measures and approve of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s performance. If anything, they want the government to

get tougher: In a mid-January survey by the broadcaster ARD, just 17 percent of respondents said the current measures “go too far”; 53 percent believed the measures are appropriate, while 30 percent said they should go further.

Indeed, because conspiracy theorists constitute only a small minority, I had hesitated to write about them: Why give attention to what’s clearly a fringe? In recent months, however, it’s become clear the Querdenker and wide range of conspiracy theories its supporters espouse can’t be ignored. The movement’s rise, coupled with its leaders’ and supporters’ ability to harness social media to help spread their message, means they pose a significant threat to efforts to contain the virus. As the world saw in Washington, D.C. last month, those kinds of insulated and invented worldviews, when left to fester, can have violent and even deadly consequences.

* * *

Although Germany’s far and extreme right are not the primary organizers of the anti-corona protests, they have been a natural fit for parties like the AfD, parts of which already deal in a potent mix of conspiracy thinking and racist, anti-Semitic tropes. Anyone who has heard AfD politicians or supporters blame the Hungarian-American philanthropist George Soros for the refugee crisis, or insisted a “global elite” is pulling the strings in national politics, will recognize the idea that Bill Gates is behind the coronavirus or the vaccines are intended to control us as in the same vein.

Teune, the sociologist, sees a direct parallel between the AfD’s unofficial ties to the Querdenker and to another grassroots movement: The anti-immigration, anti-Islam Pegida, which began its weekly marches in Dresden back in 2014. Throughout its existence, Pegida has proven to be a fertile breeding ground for conspiracy theories: For example, the idea of the “Great Replacement,” a belief that shady global elites are seeking to end the white race by bringing refugees and migrants to Europe.

The kind of conspiracy thinking mixed with xenophobic tropes prevalent at anti-corona protests today are “the AfD’s favorite dish, it’s now simply being served with different ingredients,” Teune said.

A November poll by the broadcaster ZDF gives some hints as to who backs the protests, at least these days: Asked if they believed the demonstrations were a good thing, 54 percent of AfD voters said yes. By contrast, just 3 percent of Greens voters, 5 percent of center-right Christian Democrats and 7 percent of the center-left Social Democrats agreed. Although they don’t necessarily correspond exactly to who’s actually attending the protests, the figures offer at least some clues about where the protests fall on the political spectrum.

Although the AfD and other right-wing groups are not necessarily driving the protests, they have clearly seen the anti-corona anger as a powerful force to be harnessed. AfD leaders are split on the party’s involvement with the protests—more moderate party leaders like Jörg Meuthen have cautioned against getting too explicitly tied up in the Querdenken movement and its description of the government as a “corona dictatorship.” But others, especially in eastern Germany where the party is strongest, have either tacitly or wholeheartedly embraced the protests, encouraging supporters to turn out and even giving speeches themselves.

“In a way this comes naturally, because the prime topic of the far right has ceased: Migration is not a topic in German public discourse anymore,” said Maik Fielitz, a researcher at the Institute for Democracy and Civil Society in Jena. “And it is a way for the far right to take the corona measures, or corona as a whole, to instigate a kind of anti-government, anti-liberal, anti-democratic protest. And this worked quite well.”

Fielitz points to the AfD’s long-espoused rhetoric about government overreach as an example of a continuous narrative into which the coronavirus restrictions fit easily. “For [the AfD] it was kind of a prophecy to say, ‘Okay, now you really see what a dictatorship looks like, this is what we’ve been telling you for many years,’” he said. “This is what has been propagated for many years, and in a way these months it has been coming true: [The government] is implementing measures that are quite radical, that also change the way we interact, what our daily lives look like.”

Those I spoke with said it’s unlikely that the anti-corona protests are still bringing in swaths of new supporters like they were last summer. But the subset of the population that’s become involved is becoming more radicalized—and more prone to violence.

The domestic intelligence service, Verfassungsschutz, released a warning last month to that effect, saying that especially larger protests have “an increased potential for escalation.” The Verfassungsschutz in Baden-Württemberg, the state where Querdenken was founded, has already put the movement under surveillance for extremist activities.

A handful of violent incidents have occurred at larger protests in the late summer and fall. In August, during the biggest anti-coronavirus measures protest in the country thus far, a group of right-wing extremist Reichsbürger attempted to storm the Reichstag building, the home of parliament in Berlin. Waving the black-white-red flags of the German Reich, which neo-Nazis often use in place of swastikas or other banned Nazi symbols, several hundred extremists broke off from the main protest and pushed past a police barrier outside the building and nearly made their way inside. And in early November in the city of Leipzig, about an hour from Berlin by train, some of the around 20,000 protesters threw projectiles and live fireworks at police officers in a confrontation that dragged into the night.

In the wake of the disturbing events at the US Capitol earlier this month, the parallels haven’t been lost on anyone in Germany. Of the far-right activists who attempted to storm the Reichstag this summer, Silberberger said: “They were empowered by what happened in the US. They’ll try it again.”

* * *

So what can be done about this new “infodemic?” Governments can crack down on certain types of hate speech and pressure social media companies to deplatform extremist groups and education in media literacy, but getting true believers to give up their newfound worldviews—and the sense of comfort and community they bring—is no easy feat.

Combating conspiracy thinking needs to happen early, when people are just starting to explore their interest in it, Silberberger said. By the time concerned friends or family members realize what’s happening, it is often too late: Pulling someone out requires significant psychological work and self-reflection. To stop believing in conspiracy theories, she said, one has to work through what drove them to such thinking in the first place.

“You have to change your entire worldview and to ask the crucial questions that can be painful,” she said. “You need to deal with the trauma and the reasons you’ve stuck your head in the sand and don’t want to see things, the reasons you would rather have the simple answer than the one that may be a bit more complicated but factually correct.”

During our conversation, I reflected back on an experience I had last fall while interviewing an AfD supporter in the western city of Gelsenkirchen. I had reached out to him because of his support for the far-right party, but when we met, he wanted to tell me about his newfound passion for the Querdenken movement. Over the course of our 90-minute conversation, he outlined his conspiracy-filled worldview, suggesting, for example, that the media is owned by shady billionaires who direct journalists to do their bidding and that the pandemic is being vastly overblown in order to control citizens.

I came away from that experience feeling totally demoralized. This man had been polite, soft-spoken and friendly—and yet he lived in an entirely different world than I did. How was any sort of traditional political party supposed to win him back when they have a wildly different basic understanding of reality? What’s more, he believed he had a chance at convincing me: “I’m sure the more time goes by, the more you’ll understand my view,” he wrote me later, including some links to speeches by Querdenker leaders.

These are the kinds of conversations people across Germany (and beyond) are having with spouses, parents, friends and colleagues. I’ve heard from friends who struggle to know what to say when a childhood friend starts in on the belief that the pandemic is a hoax, then simply won’t entertain any other possibility. Others have one or both parents reposting coronavirus conspiracy theories on Facebook and don’t know how to talk with them without alienating them further. Over the year-long course of the pandemic, none of it has seemed to be getting any easier.

The one upside of the current situation, Silberberger said, is that it has drawn attention to a phenomenon that has been gaining traction in Germany for years. People who may have been passively or quietly involved in alternate worlds online are now more open about their beliefs, and many openly profess them on the streets where anyone can see them. As someone who has focused on this topic for years, she said, it’s a grim silver lining that others are finally taking the issue and danger it poses seriously.

“In a way, the Querdenker movement has done us a big favor,” Silberberger said. “Because it’s done what people like my colleagues and I couldn’t: It brought the problem out into the open and made it visible.”

Top photo: A protest against coronavirus restrictions in Frankfurt, August 2020 (photoheuristic.info, Wikimedia Commons)