PANAMA CANAL—Our boat floats 85 feet above the Caribbean Sea. Waiting at the top of the Panama Canal locks on the Atlantic side, we stare from Gatun Lake down three steep chambers directly to a new ocean.

Neither Oleada nor I have sailed this sea. Here, the notorious Caribbean trade winds whip clear water into short, steep waves. Thirty-foot waves are standard along the Colombian coast. I squint at the horizon, but it reveals no secrets about its ephemeral power. From up here, the wind touches the blue horizon and turns it silver in the midafternoon sun.

For the moment, we sit in sheltered fresh water, awaiting our turn to descend to the Atlantic. Our only danger (and a significant one) is the possibility of getting run over by ships over 4,000 times heavier than ours. Like a toy boat bobbing at the rim of a bathtub, we are dwarfed by the hulking freighters gathered at this bottleneck where fresh and salt water meet. The tub has a giant, intentional drain in it, designed to move the ships that each carry up to 53,000 tons of cargo between oceans every year.

The Panama Canal has been a shipping stalwart for the past 100 years, running smoothly to transport roughly five percent of global trade. However, increasing ship size, a spendthrift expansion project, and the impacts of climate change are all colluding to threaten the canal’s relevance in ways never imagined by the original architects a century ago.

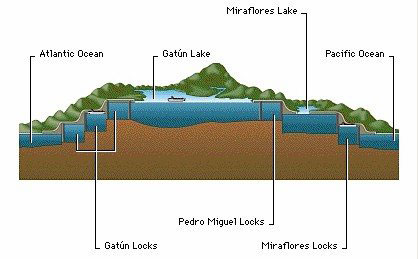

The canal relies on the freshwater passage over Gatun Lake, since transporting ships from sea level up to the level of the lake, then down the other side, requires up to 52 million gallons per ship. Descending through the three chambers in front of us is called downlocking. On the Pacific side, the locks are broken into three separate chambers spread over a mile. That protects the water in Gatun Lake: if for some reason one of the locks were to fail, the entire lake wouldn’t drain to the sea. On the Caribbean side, the locks drop a dramatic 85 feet straight from lake to ocean. All elevation is lost in three dramatic pools, like a measured mechanical waterfall.

Our “adviser,” a guide assigned by the Panama Canal Authority to travel aboard with us for the day, facilitates all logistics and keeps us from getting crushed, lost or in trouble. Harold leans back on the lifelines and chats as we wait. He tells us when and with which boat to enter a lock, and how and when to maneuver inside the lock itself. Josh drives the boat amid the dangerously powerful propwash (water moved by massive ship propellers) churning the confined water, relying on Harold’s experience to clue him into impending changes while also reacting (and contradicting Harold) when he feels Oleada to be heading for trouble. For now, Josh holds the boat steady at the edge of the lock as we wait, currents and winds swirling at the edge of the concrete.

Since Josh and Harold have both performed this task with paramount professionalism, we have extra time to wait at the top of the locks. Most sailboats miss the last daytime shuffle through the locks and moor in the lake for the night, but the coordinated efforts of Josh and our guide mean that we will be one of the few to squeak through in one day.

From Oleada’s deck, I watch as a “neoPanamax” ship grinds slowly into position. These ships are the new giants of the seas, too large to fit through the original canal before new locks were built parallel to the existing ones in a massive construction project that ended last year. Harold shares stories about the canal while keeping us out of the way of the steaming tankers on the lake. From our waiting point, he points out a significant part of the newest, $5.2 billion addition to the canal: the Agua Clara locks.

I ask again, only partially joking, if we can pass through the new locks. Harold rolls his eyes and remarks that we don’t want to: there’s no backup system for the gates.

No backup?

As we’ve seen in the 100-year-old locks we’ve entered so far, two pairs of massive steel doors swing slowly closed into a v shape, one pair at the front of the lock and one at the rear. They’re both heavy and buoyant, much like the precisely engineered ships they allow to pass.

In the new locks, the doors roll straight closed. There are still a pair on the front and rear of each chamber. But sometimes only one set will close. Despite the larger lock size—they are 70 feet wider and eighteen feet deeper—the new ships still barely fit. That, Harold tells us, means sometimes corners get cut.

This new way of operating the canal wears on Harold, and it slips out in his sarcastic comments. When he points out the difference between the locks, one in particular concerns our guide. To make the new system adhere to a rock-bottom budget, the authorities decided against instituting the old version’s most trustworthy system, not only the control mechanism for ships in the locks but the only way the canal could have been built: railroads.

Locomotion to the Ocean

We motor into the first Gatun lock chamber ahead of our “normal” sized container ship and tie to a boat already anchored to the south wall. We watch as the container ship pulls to within 50 feet of our stern. The proud bow comes toward us with alarming speed and nearly extends over us before it finally stops. It’s an image sailors’ nightmares are made of.

But we need not worry: the ship is precisely controlled from multiple points on the side of the canal. Small, electric locomotives called “mules” control side-to-side motion and braking for the ships on both sides of the canal (for forward motion the ships use their own engines). These stout and compact workhorses have proven their worth for more than 100 years, tested by time, increasingly large ships and wild weather conditions.

Locomotives work at the historical and modern-day heart of the canal to ensure its smooth function. It would not be faster to build a canal today than it was a century ago thanks to the rail lines. It was the efficient use of a constantly operating railroad that moved massive amounts of earth away from one particularly slippery, regularly collapsing hole that took seven years to carve into the jungle.

That dig, called the Culebra Cut connecting the Pacific coast with Gatun Lake, was the main challenge for building the canal. Today, it’s still only wide enough for a single neoPanamax ship at a time, effectively turning the canal into a one-way street. Carving away a mountain for this small section of the canal was what first bankrupted the French in their failed attempt to build the canal before the United States took over. It wasn’t just any mountainside: as workers removed the top layers, the reduced pressure on the compressed mud below freed the lower layers to move, sliding and filling holes that had taken months to excavate.

During the building of the canal, construction of the locks themselves were a minor side story compared to the seven-year war of machine versus mud that took place to dig the channel. In total, some 96 million cubic yards of dirt were removed. The cut caused hundreds of deaths thanks to the dangers of working with explosives and the tendency of the underlying layers to slough away in massive landslides. “It was, in fact, a tropical glacier—of mud instead of ice,” one of the canal’s chief engineers, Major Guillard, recalled in Scientific American. The passage was not merely dug, but dug and re-dug as the earth slipped back into the man-made wound. In one ten-day period, 500,000 cubic yards of mud sloughed back into the dug canal.

The only way it finally became possible to finish the section was with the use of a railroad, thanks to the ingenuity of constantly cycling rail cars, the brainchild of railroad engineer John Stevens. Train cars ran day and night, meeting the hardy mechanical shovels and their loads for seven years straight.

The legacy of railroad ingenuity carries forward to the present day. One of the most-often cited points of pride among employees are the mules, the Mitsubishi-made electric locomotives that control the ships in the locks. The canal employees are quick to point how just how finely tuned the entire system is because of those workhorses; their genuine admiration slips through in interjected praises.

“Have you seen the mules?”

“Well, the mules make it all work.”

“Smart guys, here in Panama: they say nothing happens in Panama.” Harold’s snide comment catches me off guard. He’s watching two tugboats guide a massive neo-Panamax ship into the new locks adjacent to ours as we wait for the water to drop. He shakes his head. Over the course of our long day with him, I begin to understand that his scorn stems from a deep, personal pride in the workings of the canal and his twenty years of experience here.

There’s another major difference between using mules versus tugs: the mules are electric and rely on the clean hydropower provided by the Gatun dam. Mitsubishi specially engineered the mules, and they run seamlessly—without emissions. The tugboats, on the other hand, work their 4,400 horsepower engines and add both emissions and expense in the long term—plus the increased possibility of human error.

I feel relieved that we are in a lock with a boat secured by steel cables to the sides rather than two tugs. As our water drops, the mammoth ship disappears as we start our descent. At low water, we quickly untie from our companion boat. We wait for it to move forward, then slide into the next chamber. I awkwardly send our lines like a jumbled lasso toward the deck hands waiting at the stern after we finagle our bow line to their midship cleat ourselves. I marvel at how much individual human attention and activity is still needed in the details of getting ships through the locks. It seems imprecise for us little ships, but it works.

At the bottom of the third chamber, the gates open slowly and dramatically to the ocean. We are positioned in the front and middle of the lock, and Harold gives us the cue to charge forward before anyone else. We are the first out into the sea, as the tourists on the boat beside us cheer. Oleada sprints forward into the twilight breeze, like a horse released from the gates at a rodeo. None of us turn around to watch the majestic canal fade behind us, forgotten with an entire open ocean and host of new concerns ahead.

We paid $875 for one day to avoid months of sailing through some of the most treacherous seas in the world around the tip of South America. That is the lowest amount any ship can pay, and seems laughably small when we consider the expenses and risks we would have otherwise incurred. The canal has steadfastly and without question provided this service for over 100 years for any ship that can afford the passage.

The Cost of Expansion

It’s difficult to get to know about the canal’s past and present without suspecting calculated intent behind the United States’ relinquishing control. The US ran the canal from its opening in 1914 until 1999, when it was turned over to the Panamanian government per the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, negotiated in 1976 and ratified by the US Senate in 1978. The canal was turned over to Panama the same year China began shipping with a post-Panamax fleet too large to fit through. To avoid obscurity and the ever-looming threat of a new Nicaraguan canal, the enterprise had to be expanded. The multi-billion-dollar project fell to Panama instead of Washington.

A few weeks after passing through the canal, Josh and I stand at the railing of the new visitors’ center on the Caribbean side and watch puffs of exhaust disappear into the wind as the tugboats work to keep a neoPanamax ship in line in the Agua Clara locks. As the ship enters the lock, a squall washes over with sheets of rain and destabilizing wind. It’s hard not to gape over the tiny margin for error: the ship appears to deal in inches, not feet, of wiggle room. Josh makes himself a human tripod for his camera for 30 minutes of time-lapse, and watching the footage, we can see just how much the ship rocks and leans, bucking the pull from the hardworking tugs and the unpredictable wind.

But the basins catch only some of the water, and the new locks strain a system that has already felt the effects of climate change in drier days. With less water, the larger draft (deeper) neoPanamax ships must lighten their loads so they don’t drag on the bottom of the lake—so much so that in September 2016, the larger ships could carry no more than the older, smaller ships.

All that for an estimated $5.25 billion dollars in construction costs. In the country with Latin America’s second largest wealth disparity, where 40 percent of the indigenous population lives in extreme poverty (on less than $1.90 per day,) this staggering amount of money is a painful reminder to ordinary citizens that commerce trumps everything else in Panama.

Perhaps even more jawdropping is that the original projected budget came in at $3.1 billion from a Spanish-led consortium, the United Group for the Canal (GUPC), $1 billion cheaper than the offer from the next-highest bidder. Among other problems the impossibly tight budget imposed, poor aggregate was mined from the Atlantic side of the canal for the concrete, and the new locks already have worrying leaks. The rail system—the backbone of canal construction and function for 100 years—was foregone for the cheaper (in the short term) tugboats. Amid all that, tensions ran high and president Ricardo Martinelli and his administration went down as the most corrupt in modern memory.

The project ended with $3.4 billion in disputed costs, not to mention rotten concrete in the locks, faulty tugboats that run the entire operation and veteran canal workers waiting in disgust for the other shoe to drop: catastrophic failure, financial ruin or both. Harold tells me that ship fees have increased five times in the last eight years to help make up for shortfalls.

“When the Americans ran it, it was ‘pro mundo beneficie,’ for the benefit of the world. Now it’s all about profit for just a few.” It’s hard to reconcile Harold’s unusually favorable opinion of the United States. But as much as I can appreciate the American ability to build and maintain infrastructure, canal workers can do the same. The slow slide toward degradation, physically and financially, visible only from a long-term perspective, strikes at the pride of canal workers. For Harold, it’s wearisome to have an insider’s view of what both Americans and Panamanians have been taught is one of humankind’s greatest achievements slipping slowly toward neglect.

The crucial lesson learned when the canal was first built was to never underestimate the power of the jungle. That lesson is being reinforced by climate change. For the last two years, we’ve heard repeated reports from citizens as we traveled the coast: the rains are inconsistent with the seasons, the storms significantly more powerful, and the years are increasingly hot and dry. This information lines up exactly with historical and predicted climate models. The conditions stress natural systems and the people that depend on them—and the canal is the combination of those two things.

This conundrum reflects what we have seen throughout the Mexican and Central American coasts. With a corrupt political system, persistent poverty, and decisions made for short-term financial gain, the canal system already weakened by such factors becomes even more vulnerable in the face of drought and severe storms.

When an excavation manager for the Pacific side was asked about his resignation during the building process, he recalled an old Spanish saying: “Lo barato sale caro.”

That which is cheap becomes expensive.