Can writers transcend archetypes, stereotypes and other misguided expectations?

When I met an editor from an American newspaper five years ago, I sought guidance for crafting the perfect pitch. Having just begun working as a journalist in Cairo, I was developing an expertise in Arab political comics. The editor’s response was blunt: The rag was likely to publish a piece about Egyptian cartoonists only with a jolting news peg, such as a killing or arrest. The publication, it seemed, had a certain idea of how the story of caricaturists abroad ought to be told. It wasn’t about cultural criticism so much as the stark binary of the pen versus the sword.

In the aftermath of the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks, however, cartoons became hard news. As the world tried to make sense of the heinous killings, the resilience of Arab and Muslim cartoonists in the face of violent extremists and intolerant governments had become a headline-making concern. I wanted to share their voices. But I was wary of callously seizing on a catastrophic, newsworthy event or dumbing down a complex story. Rather than responding immediately, I drafted and redrafted several pieces, agonizing about the story I wanted to tell. Eventually, I published a number of essays over the winter and spring that aimed to deepen the conversation about Islam, free speech and the art of caricature beyond the immediate tragedy.

Cultural journalism holds the potential for deepening the discourse surrounding power politics, getting to the heart of society in a way that “hard news” doesn’t. Of course, that can be easier said than done when one has to pitch the product to a gatekeeper in Washington, London or New York. The task of the feature writer on the front lines is to consider art exhibitions or literature, to name a few, without the pressure of extracting from them a certain political message or takeaway. Arab artists, curators and cultural producers working inside and outside the Arab region needn’t fit into any particular mold, and we journalists must recognize the power we have to break stereotypes.

It’s no secret that reporters often begin foreign assignments with preconceived notions. Throughout a half-decade of reporting on arts and culture in Egypt and the wider Middle East, I have often experienced a tension between how the region is seen from afar and how I have experienced it. Amid the 2011 Arab uprisings, publications sought archetypes like the revolutionary graffiti artist, young political activist or local writer who serves as a bridge between cultures. The best stories, however, don’t provide the comfort of such easy classifications; they break down barriers and show personalities or perspectives that transcend prefabricated frames. As journalists, what can we do to more accurately and truthfully cover cultural currents?

I had the opportunity to hear several voices discuss that question during ICWA’s June symposium, “The Politics of Art in the Middle East,” which I convened at the end of my fellowship.

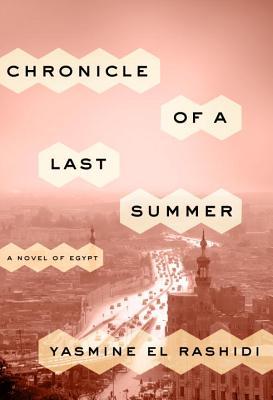

One of the speakers, Yasmine El-Rashidi, a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books and chronicler of political change in Egypt, proposed working outside the strict parameters of journalism. She had previously served as The Wall Street Journal’s Middle East correspondent, taking over regional coverage in 2002 after the brutal slaying of the paper’s reporter Daniel Pearl. In the shadow of the 2011 uprisings, El-Rashidi was commissioned to write a nonfiction book about the Egyptian revolution. “I realized quickly that there was an expectation of the kind of book that I would write… from publishers, from editors,” she said in the panel discussion, “the book by the Egyptian girl about the revolution.” But for El-Rashidi, the stakes were too high to produce an obvious tome. “It risks being the native informant, the native narrator,” she said. “I don’t want to reduce things; I don’t want to reduce a narrative.” So she decided to write a piece of fiction instead.

Her resulting volume, Chronicles of a Last Summer, doesn’t address the Egyptian revolution or 2013 coup head-on, but lets them sit uneasily in the background. Others have taken similar approaches, notably the filmmaker and columnist Omar Robert Hamilton in his new novel The City Always Wins. The common denominator is that fictional narratives allow authors the freedom to write about their country and the quotidian aspects of Egyptian political change.

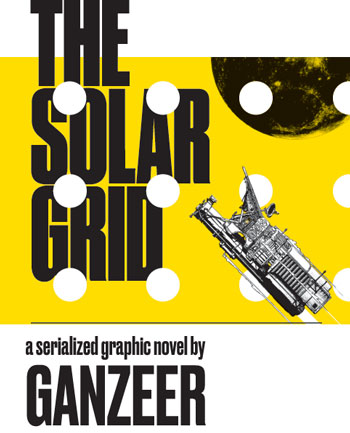

Another panelist, Ganzeer—the pseudonym of the prominent Egyptian graffiti and visual artist Mohamed Fahmy, who has been living outside Egypt since 2014—also felt pressure from the outside. “There are certain markets that are attracted to certain subject matters,” he explained at the June symposium. Little wonder then that when LA Weekly profiled him a month earlier, it un-ironically declared him the “Banksy of Egypt” in the headline. Not exactly how he sees himself. Ganzeer is creating a graphic novel called The Solar Grid, a science fiction narrative that envisages the dystopic effects of climate change. But he has been able to support the project only through an online crowd-funding campaign. Expectations are part of his reason for turning to readers for support. “If I was to declare or just put a post online that I am working on a book that was critical of my Islamic surroundings during my upbringing, I will have 20 publishers approaching me,” he said. “If I was to do something that was critical of the West, there’s no way it would get funded unless I’m already very, very popular.” Thankfully, he is popular, and his Kickstarter campaign was successful.

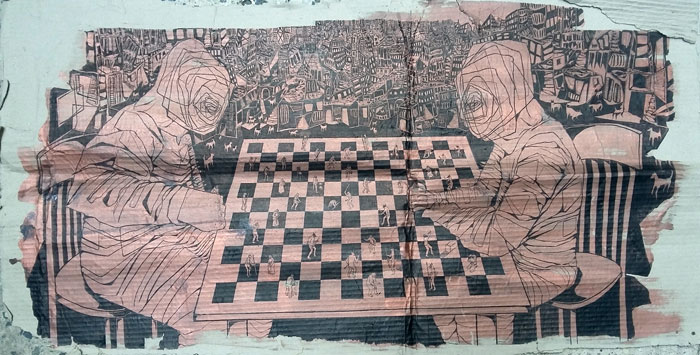

Speaking alongside Ganzeer at the Washington symposium were the curator and art historian Maymanah Farhat and the Egyptian artist and journalist Ali Abdel Mohsen. In her description of Syrian artists working abroad, especially in Germany, Farhat offered a mirror image of Ganzeer’s. “There is this pressure to ‘perform,’” she said. “You have to have all the buzzwords. Refugee crisis, the war, and civil unrest.” She quipped that we—as writers and curators—ought to all start a pact that we’re not going to participate in such stereotyping. (I’d sign on the dotted line.)

Ali Abdel Mohsen shared a similar sentiment. An accomplished fine artist, he has also written widely for Egyptian news outlets. He famously interviewed a Cairo lion tamer for a comic profile that went viral when it appeared in Egypt Independent, the English-language newspaper. (Harper’s later republished it). On the sidelines of the symposium, Abdel Mohsen told me that he had stayed in touch with the lion fighter, who had been hit by a stray bullet at a protest. The gladiator died a slow death in a Cairo hospital bed. The experience left Abdel Mohsen keenly aware of the journalist’s responsibility. “It’s not just about interesting characters because you don’t want to turn actual people you meet into characters that you are exploiting or anything,” he said, explaining that subjects ought not to be objectified. “It’s more the sense of: we should pay more attention to this.” That’s why, years later, his dispatches from the margins of Egyptian society retain their urgency.

What I have learned through my own work is that there is no single way to overcome such challenges except through diligent and meticulous research. It is indeed difficult to convey the complexity of a person’s character in a format that sometimes seeks to reduce him or her to a larger political position. I encountered that issue when writing a profile of the Egyptian cartoonist and rabble-rousing satirist Andeel. I had drafted a piece that detailed how he had flouted taboos and laws by caricaturing the Egyptian president. But Andeel himself was skeptical of such a one-dimensional narrative. “I don’t want my work to be only interesting because of dictatorship because this is again giving dictatorship so much size and importance,” he told me at the time. “I hate when people see cartoonists as exotic—the expression of freedom fighters in the Middle East.” I worked those counterintuitive quotes into the piece, which enabled me to present a more nuanced view of his work.

titled “New Folder,” at the Nile Sunset Annex, February 2015

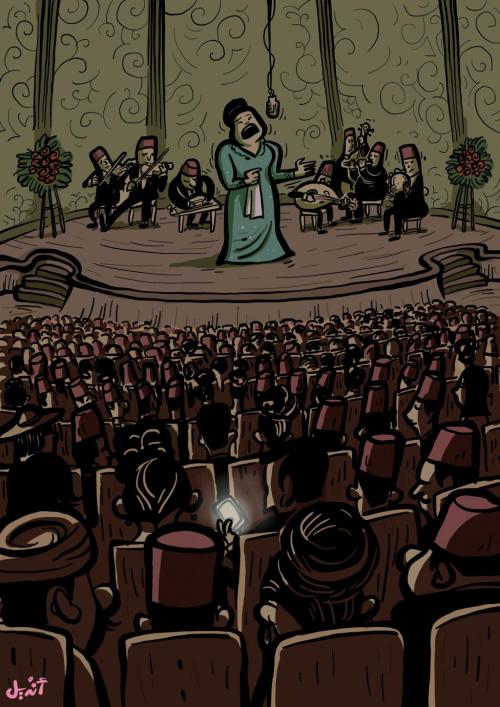

There are other ways to convey the intricacies of an artist’s portfolio beyond headline-capturing issues such as censorship. I continue to follow Andeel’s cartoons because a two-page spread can’t possibly encapsulate a person’s entire career. In blog posts, I have the luxury to write unconstrained commentary and grapple with issues that I simply find interesting or important, regardless of the wider appeal they might have to the mainstream media. In one post, I closely read Andeel’s cartoon of the late Egyptian pop star and darling of the Arab world, Oum Kalthoum; it was a meditation on the aesthetic choices made by him as a cartoonist, delving into how a striking drawing fit into his oeuvre. Although I wrote the piece because of my own personal interest, it was gratifying to hear Andeel’s response. “I’ve long found it infuriating that journalists have a mono-focus on the political value of my cartoons, specifically their relation to freedom of speech,” he wrote to his 80,000 followers on Facebook when sharing the article, “so it’s extremely refreshing and useful to see what kind of visual value the work carries through someone else’s eyes.” It was a small sign that I was on the right track.

It may sound rich for a journalist like myself to wax poetic about representation. When writing for American or European publications about the Middle East, I navigate tricky waters and inevitably oversimplify some aspects of the subject I’m working on, whatever it is. I am fully aware that I haven’t been able to solve all the problems that El-Rashidi, Ganzeer, Farhat and Abdel Mohsen raised at the symposium. But they are provocations that I will keep in mind while working on my next stories.