TROMSØ, Norway — “Welcome to Tromsø, the Arctic capital!” said Mayor Gunnar Wilhelmsen, standing at a podium inside an expansive auditorium. Around his neck, a silver chain held a dark blue plate embossed with a reindeer: the municipal coat of arms.

“You may think you have arrived in a small town at the end of the world,” he added in a clipped Norwegian lilt. “Truth is, you are front and center of world events.”

A strong statement perhaps. But from a polar research perspective, the building in which Wilhelmsen was speaking helped his argument. The Fram Center is a 264,000-square-foot, glass-walled waterfront hub just south of the city center. Here, 500 employees at 21 of Norway’s foremost research institutions—including the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Institute of Marine Research, the Norwegian Meteorological Center and many more—share a roof, making it by far the largest research center north of the Arctic Circle. (For comparison, the Canadian High Arctic Research Center in Cambridge Bay is 52,500 square feet and has 91 employees.)

Built in 1993 and expanded in 2018, the structure isn’t merely a shared office space. It’s a complex nucleus of laboratories, vaults and auditoriums, with 350 annual events attracting 8,000 visitors from around the world. Inside its walls, the “FRAM” research cooperation represents a decades-old vision to bring a cross-disciplinary approach to study the climate, environment and societies of the Far North.

More recently, however, the Fram Center has added new tenants that complicate its stated research aims. Since 2013, it has also headquartered the Arctic Council, a diplomatic forum between the eight Arctic states and six Indigenous organizations. And, last October, the center’s newest addition caused controversy: the brand-new “American Presence Post,” the northernmost US diplomatic outpost.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, the United States has heightened its involvement in the European Arctic, including with an expansion of military access to dozens of new bases in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Many of the Fram Center’s researchers have raised concerns about bringing a branch of the American government, however small, into an independent, international research space.

In fact, the co-tenancy of science and geopolitics is not unusual. The current tension is in keeping with a long tradition of polar achievements powered by technological and territorial competition between nation-states. The Fram Center is partly a symbol of Norway’s historic dominance of this race. The Fram (Norwegian for “forward”) was the three-masted schooner that carried the country’s two most famous polar explorers, Fridtjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen, on expeditions to each pole. Those voyages were nationalistic performances as much as strides for science.

During the past century, national investments in polar science have often served ulterior motives: from mapping new shipping routes to detecting natural resources to launching satellites that gather intelligence along with scientific insight. And there’s an even more complicated legacy: the idea that the Arctic is uninhabited and unknown, to be charted by heroic men and claimed by competing nations.

* * *

On a late October afternoon, snow flurries cascaded along the Fram Center’s two-story glass windows, striping the lobby’s floor with streaked shadows. Near the main sliding glass doors, a taxidermied polar bear stood frozen mid-stride, baring his teeth.

“PLEASE DON’T TOUCH SIVERT THE BEAR,” read a sign next to the animal, so I leaned in for a closer look at the coarse yellowed fur that once warmed this 700-lb creature through winters on Svalbard.

That’s where Helge Markusson, the center’s bespectacled communications director, found me when he emerged from a secure glass door. “I’m one of maybe 10 people with a key card that opens every door in this building,” he said cheerfully, holding the door open, ushering me into the heart of the massive research complex.

Down bright hallways lined with photographs of past polar ventures, we emerged into a vast open atrium, light spilling through its high glass ceiling that unites the old building with its addition. On either side of the space, three floors of office windows hinted at the work of over 500 researchers, from meteorologists to glaciologists to terrestrial biologists. Deep below our feet, the Norwegian Polar Institute’s freezer vaults were filled with decades of sea ice cores from around the Arctic. Through the floor-to-ceiling windows to the east, snow-covered boats gently rocked in docks from which dozens of north-bound research expeditions depart each year.

In 1993, parliament voted to move the Norwegian Polar Institute from the capital Oslo some 700 miles north to Tromsø, to position its global research heavyweight north of the Arctic Circle. At the time, Norway had good reason to invest in the high North: In the aftermath of the Cold War, Arctic military competition was quickly transitioning to scientific rivalry. At the same time, northern populations were rapidly declining as young people flocked to new industries further south.

From 2007 to 2008, a United Nations-designated “International Polar Year,” the world’s nations came together for the first-ever global polar scientific collaboration. That year, Norway added eight more institutions to this building, called it the “Polar Environmental Center” and invited those organizations to collaborate. In the resulting 2008 International Polar Year report, a groundbreaking document that helped establish the Arctic’s outsized role in climate change, the center punched far above its weight: 28 of the report’s 63 research projects originated here.

That success inspired a more ambitious scheme. In 2010, the Norwegian Climate and Environment Ministry launched the FRAM research initiative, growing the partnership to 21 institutions. Its $50 million fund supports cycles of four three-to-five-year projects, and 10 to 15 one-year projects. (They’re currently about mid-cycle on a 2021-2026 set of grants.) The shared space was designed to facilitate cross-pollination, removing literal barriers to collaboration across disparate fields.

“If you get an idea, you can take someone out for lunch or coffee and come up with something you’d never think of on your own,” Markussen said.

But the Fram Center (somewhat confusingly) isn’t just home to FRAM research. Across a set of secure doors lies a completely separate wing: for the Arctic Council Secretariat, the International Center for Reindeer Husbandry, the Norwegian coastal data hub Barents Watch, and, most recently, the three-person “American Presence Office.”

The former three organizations, Markussen told me, were uncontroversial additions. The American Presence Office was a different story. Chinese and Korean scientists in particular, who have permanent research posts in the building, voiced concerns about housing an outpost of the American government, he said. To Markussen, however, it’s not such a far-fetched idea—after all, the Fram Center is a government building, and the United States is an important ally.

“Some scientists had concerns about what was happening here—is this a spy office and some such?” he said with a chuckle. “But this is a part of being Norwegian. International cooperation matters.”

The seeming contradiction is in fact in keeping with the center’s mission, Markusson said, to create more pathways for exchange between disciplines and nations alike. Just as research investments can advance nationalistic goals, scientific collaborations can further diplomatic ones. That is particularly true of Arctic research, where complex natural systems like oceans, ice, permafrost and rivers transcend national borders. Especially since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine halted scientific cooperation with half of the geographical Arctic, every step toward transparency matters.

“All the things we do in the Fram Center are a dialogue, among institutions, among countries and among people,” Markussen said. “It’s perfectly natural that we touch into politics, we touch into science, we touch into society.”

Still, he acknowledged that the Fram Center is an obvious geopolitical symbol. Look no further than the building’s name, he said. “The government gave us three choices: Nansen, Amundsen or Fram,” he said with a chuckle. “They clearly had the Norwegian legacy in mind.”

But which narratives of the North does the Fram legacy move forward, and which does it risk leaving behind?

“Such a people are the Eskimos, and among the most remarkable in existence,” the Norwegian zoologist and Arctic explorer Fritdjof Nansen wrote in his book Eskimo Life, published in 1893. “The tracts which all others despise he has made his own.”

I found the volume carefully archived in the musty stacks of the Polar Library, tucked away in a far corner of the Fram Center’s ground floor. Five years before he boarded the Fram to set out for his ambitious North Pole attempt that brought him international fame, Nansen had spent a long winter among the Inuits of Greenland (then called Eskimos by Europeans). He was quickly humbled and enthralled by their seeming ease in a hostile world.

The era of polar exploration was the turn-of-the-century equivalent of the space race: a state-backed competition to chart new territories and, in doing so, lay symbolic claim. Much like the first men in space, polar explorers were international celebrities, universally worshiped for their physical fitness, scientific acumen and life-risking boldness. To most of the world, the North seemed as alien as the moon, with mysterious icescapes that captured the global imagination. (After Nansen’s harrowing 1893-1896 North Pole attempt, Sigmund Freud contemptuously wrote about his family’s “hero-worship” of the explorer. Still, even he admitted to his own dreams of joining Nansen on a “field of ice.”) Remarkably, over a roughly 30-year period, the most groundbreaking ventures to either pole were made by just two Norwegians: Nansen and Roald Amundsen, who reached the South Pole in 1926.

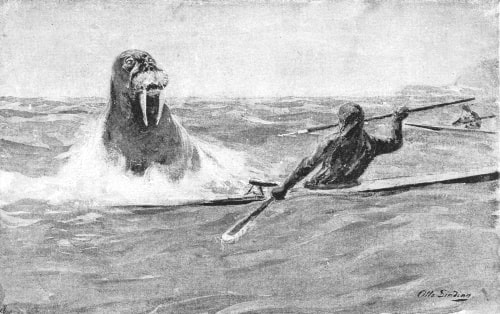

Unlike space, however, the turn-of-the-century Arctic was far from uninhabited. And much of the technology behind the polar explorers’ success wasn’t new or particularly Norwegian at all. From the North Pole to the South, both Nansen and Amundsen attributed their survival to time spent with Arctic Native peoples who best understood surviving the planet’s harshest landscapes. After Nansen’s 1893 expedition left the Fram ship stuck in pack ice, he credited his harrowing journey home (with a team of Samoyed dogs and sleds) to what he had learned from the Inuit during his Greenland visit years earlier.

Similarly, in 1911, when the Fram carried Roald Amundsen to Antarctica, international media breathlessly followed his ice-crossing race against the British explorer Robert F. Scott to reach the South Pole. Unlike Scott, who wore wool and used heavy horse-drawn sleds, Amundsen donned animal skins and relied on lightweight dog sleds— methods learned from his time with the Inuit on King William Island on the border of the Northwest Territories. When Scott finally reached the South Pole in January 1912, the Norwegian flag planted by Amundsen had already gathered a month’s worth of snow.

* * *

From the wetlands of the Tana Valley in northern Norway, the Tana River wends a winding 224-mile path northeast between Norway and Finland before spilling into the Arctic Ocean. The indigenous Sámi name for the Tana, deatnu, means “great river.” And it is indisputably great: For centuries, it brimmed with the planet’s largest population of wild Atlantic salmon. Today, it is under threat. After a staggering 25-year salmon population decline, both Norway and Finland closed the river to fishing in 2021 and 2022.

Just like the river, the Sámi people who live in this region transcend national borders, with knowledge and language that long predates state territorial lines. From the mid-1800s until the 1980s, aggressive official campaigns banned indigenous language and cultural practices, and steady development damaged the Sámi traditional way of life. So, too, did overfishing, development and contamination by the two states on either shore damage the life of the river.

One of the FRAM research fund’s current three-year projects, “Tanaelva,” (Tana River), brings Sámi traditional knowledge into conversation with Western science, and Sámi peoples into dialogue with the local Finnish and Norwegian authorities, to create a more sustainable path forward. The idea was born in the Fram Center, in conversations between researchers from the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research and the Norwegian Center for Cultural Heritage. The project, its leaders wrote in a press brief, confronts “a fundamental problem related to sustainable management: how to get different interest groups with different views and interests to work together on natural resource management.”

Historically, Tana River management has been a top-down process, with economic-driven fishing and contamination limits set by a confusing checkerboard of state and municipal regulation. The new project turns that model on its head, bringing together the river’s many stakeholders to design a bottom-up approach that begins with the needs of the communities and ecosystems it supports. The work demands reimagining how we talk about a river: not just in terms of the resources it provides but as a crucial earth system possessing an inherent value beyond human use.

With the project, FRAM is following a growing trend in Western science to incorporate, and learn from, the traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous peoples. This isn’t only a more just approach, it’s a sensible one. The past two centuries of extractive industry—from fossil fuel companies to salmon fisheries—have stressed global ecosystems close to a breaking point. But thousands of years of accumulated knowledge offer lessons in sustainability. Many “new” concepts proposed by climate leaders are in fact rooted in long-established practice, much like the tried-and-true technologies that powered polar explorations. Take for instance the “ecosystem-based approach” to fisheries management that prioritizes ecology over economics, or the recent legal momentum of “intergenerational ethics” that hold us responsible for the rights of our descendants. Both reflect Indigenous ways of thinking.

Other current FRAM projects also spotlight Indigenous knowledge. Among them, “CoastShift” examines possibilities for more sustainable food production along northern Norway’s coasts, bringing together 42 researchers from eight institutions including marine ecology, fisheries, maritime law and Indigenous studies. And “KnowledgeScapes” examines a conflict over a northern Norwegian copper mine on Sámi reindeer herding and fishing territory, aiming to create more equitable models for dialogue and decision-making about the uses of land and sea. (I reported on the conflict for National Geographic in 2021.) At the center, regular “Fram Talks” have also highlighted far-from-determined questions about how to co-produce knowledge with Indigenous peoples. That doesn’t erase colonialism, nor does it correct a structural bias toward Western authority. But it’s a start.

“This is an ongoing discussion,” Markussen told me. “We can be better in the dialogue with local inhabitants, including Indigenous representatives.”

After the Cold War, a new narrative about the Arctic emerged, that borders don’t have to create tension—they can also facilitate exchange. And the 1990s heralded an era of previously unimaginable cross-border scientific collaboration. That was due in no small part to the 1996 establishment of the Arctic Council, which funds more than 150 ongoing circumpolar scientific projects. The council remains the highest diplomatic forum that includes Indigenous peoples as equal stakeholders. So it may make a kind of sense that, in the Fram Center, it shares a roof with groundbreaking collaborative science. Arctic science in particular needs diplomacy—to transcend borders and consider the region as interconnected as it is.

Yes the Fram Center is an unapologetically nationalistic symbol, affirming Norway as a polar research powerhouse. But that needn’t be nefarious—power can shift paradigms, after all. With recent investments in projects that center Indigenous knowledge, FRAM may be taking one step toward fulfilling a lesser-known legacy of its most famous explorers, striving for cultural exchange and crediting the knowledge of this region’s first inhabitants.

Top photo: A taxidermy polar bear guards the entrance of the Fram Center