TROMSØ, Norway — Splayed like an octopus on a patch of grass near the harbor, the tangled orange-and-blue fishing net formed a coarse snarl, studded with buoys and dragging dark kelp. Beside it, two barrel-sized white bags were brimming with worn plastic bottles, twisted and bent like driftwood. Those artifacts, recently collected from Norway’s northern coast, represented just a tiny fraction of the planet’s marine litter.

“These came from our latest Finnmark expedition,” a tall young man in a green survival suit told an assembled crowd, lifting a dented orange basketball-sized buoy.

The man was no typical beachcombing volunteer. He was part of Norway’s newest ranks of full-time “coastal renovators,” trained to navigate rough conditions and sensitive habitats to clear litter from the country’s most remote coastlines. Over the past four years, thanks to the work of renovators like him, Norway has been reinventing beach cleanup on a historic scale. On this particular morning, they were sharing their model with the world.

On September 20, Tromsø hosted the first-ever annual “World Cleanup Day,” an event established at the December 2023 United Nations General Assembly to raise awareness of the harms of plastic pollution. The day’s theme, “Arctic Cities and Marine Litter,” highlighted the unique challenges to the planetary North. As the first snowfall brushed Tromsø’s mountain peaks and icy winds swept through the narrow streets, dozens of representatives from government, industry and nonprofits around the world gathered in this small northern-most city to discuss the persistent problem of pollution—and learn about Norway’s novel solution.

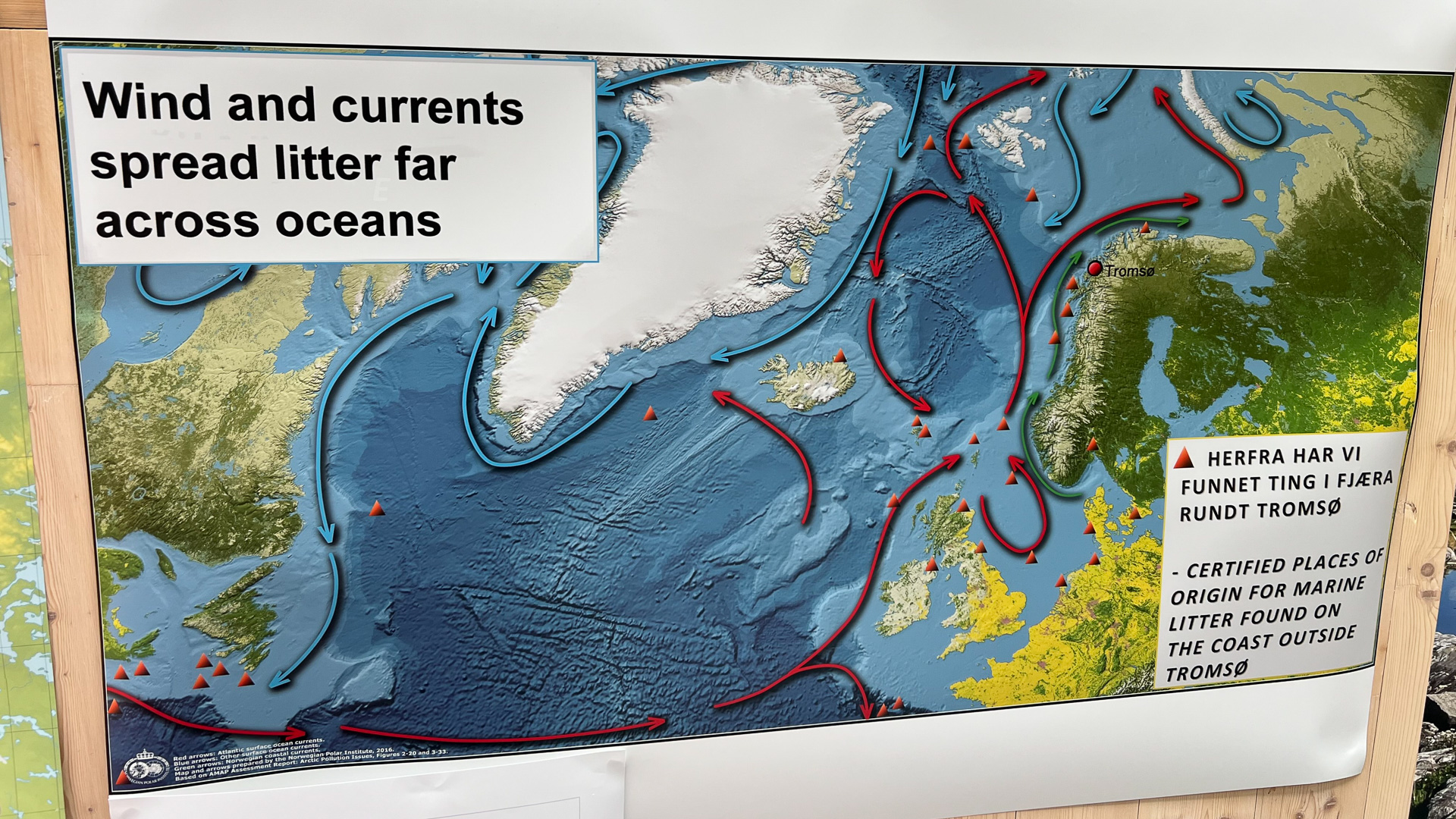

As both an Arctic and a coastal city, Tromsø is doubly vulnerable to the world’s pollution. The vast majority of global plastic ends up in the ocean: By 2050, there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish, according to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). And the flow of global currents carries much of the debris north, often delivering it to shores otherwise untouched by humans.

In these fragile ecosystems already rocked by record-setting temperatures, animal species end up choked, entangled or poisoned by toxins released as plastics degrade. Clearing plastic from shores is the best way to prevent the breakdown of litter into toxic microplastics. But due to seasonally impassible conditions and fragile habitats for threatened organisms, Arctic coasts are extremely challenging to clean.

Norway’s strategy is so intuitive it’s hard to believe it’s one-of-a-kind: Every cent spent on plastic bags goes directly to plastic cleanup. In 2017, the European Union mandated that every European country observe an annual maximum of 40 plastic bags per inhabitant by the end of 2025. Most nations imposed a plastic tax that went to more general government funds or recycling education. In Norway, however, a coalition of its largest retailers formed the Norwegian Retailers Environment Fund (NREF), for committing all plastic bag revenues to plastics solutions. By 2019, the fund was big enough to employ a national corps of full-time coastal cleaners. Over five years, NREF hasn’t just cut the number of bags sold by more than half, it’s accumulated more than $225 million, enough to expand its work internationally. Today, it funds more than 1500 plastic solutions projects across 60 countries.

Cleaning Norway’s beaches is no small project: With 17,000 miles of inlets, fjords and peninsulas, this country boasts the world’s second-longest coastline, after only Canada. But in just two years, from 2021 to 2023, the “Clean Up Norway in Time” initiative eliminated 40 percent of it: picking up 3,700 metric tons of trash from a perimeter that, the project boasts, could stretch “from Oslo to Brisbane and back.” And the organizers are far from done: They plan to clean half the coastline by 2025, and 70 percent by 2028. Since January of this year alone, the expanding staff of 140 or so coastal renovators has logged 1,950 cleanups. (A seasonal group of young volunteers also helps. NREF funds a program that provides food, training and lodging to international crews of summer beach cleaners.)

“The best thing is, anyone can replicate our model. There’s no catch, no financial incentive for us,” NREF communications director Stian Kallekleiv said. “We’ve already cleaned, for example, the equivalent of the entire United States coastline. The model is there for the taking.”

The world’s nations may soon need to take note. Since 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly has been negotiating the first-ever legally binding intergovernmental plastic pollution agreement. This December, member states will gather in South Korea to finalize the inaugural “Plastic Treaty,” which aims to end plastic pollution by 2040. For the first time in the 117-year history of its production, we will have global standards for the production and disposal of plastic.

* * *

For millennia to come, the Anthropocene will be stamped in the geologic record by an unmistakable synthetic layer. Since the first plastic was synthesized from petroleum in 1907, these materials, in all of their various ductile and inherently “single-use” iterations, have become the bendable backbone of modernity. From the pipes in your house to the fibers of your tee-shirt, plastic is inescapable. I’m touching plastic to write this dispatch just as you’re likely touching it to read it.

The world embraced plastic for the promise of disposability. As it turns out, that was an illusion. Plastic may break down to microscopic parts but it persists in our environment, flowing in our waterways and concentrating in the world’s oceans. More than 430 million tons of plastic are produced each year, according to UNEP, and two thirds are cast aside as waste after just one use. Eleven million of those tons end up in our oceans annually, adding to the 230 million metric tons already circulating in our seas.

The most visible problems with plastics are obvious: They clog shorelines and disrupt habitats, strangling sea turtles and choking birds. But the larger danger occurs as they begin to break down. All plastic eventually becomes “microplastic,” or pieces smaller than five millimeters—which accounts for 92 percent of plastic in the oceans. Microplastics are not just pervasive, they’re harmful to animals and humans alike. In 2022, scientists detected microplastics in human bloodstreams for the first time. Just this summer, a study by the National Institutes for Health discovered microplastics in the human brain.

Still, there’s hope: Evidence shows that simple clean-up goes far. Removing large plastic pollution from marine environments can reduce the prevalence of microplastics there by a staggering 90 percent, according to NREF. Dramatic reductions in plastic waste are also entirely possible—indeed, we’ve barely begun to try. That’s the work of the forthcoming Plastics Treaty, which would set an ambitious goal to end plastic pollution by 2040. That would require international standards for building a “circular economy” for plastics: We can’t stop using plastic but we can go a lot farther in reusing the vast quantities we have already produced.

On the morning of September 20, World Cleanup Day kicked off at the Fram Centre, a waterfront research hub, with a series of speeches by officials and activists. Then a data scientist took the stage. Marte Haave, a senior member of the marine pollution research organization Salt, is helming another NREF initiative, to analyze and trace the sources of plastic after they’re gathered. She leads a sort of trash forensics team, which, all down the Norwegian coastline, is logging items from sample sites to better understand their source country and industry, tracing items’ drift paths from Norway, Europe, and even Asia and North America.

We can’t reduce plastic pollution without also knowing where it comes from. And evidence shows most marine litter isn’t really discarded by individuals like you or me. It comes, overwhelmingly, from big industry, most commonly fishing and fish farming. Buoys, nets, industrial packaging and containers: Whether they’re lost or intentionally discarded, plastic already in the ocean is much more likely to get stuck there. After petroleum, seafood is Norway’s second-largest industry. Yet, as NREF CEO Cecilie Lind later told me, its plastic cleanup work is so far entirely powered by retailers and funded by consumers. Documenting hard data about the sheer extent of fishery-based pollution, she hopes, will enable policymakers to push the industry to take more responsibility for solutions.

If the Plastics Treaty is as effective as many hope, Salt’s data over the coming years may reflect serious reductions in plastic waste. But that is far from a foregone conclusion. Over coffee between presentations, I spoke with Lars Stodal, senior expert in marine litter at the environmental nonprofit GRID-Arendal, which co-hosted the day’s event. He told me that with just a few months left, treaty negotiations are still heated. Norway co-leads the “most ambitious” coalition, pushing to target pollution at every stage of the plastic lifecycle by establishing common standards for chemical additives and limits on virgin plastic.

The United States, notably, is working to scale back that ambition—wary of measures that might limit industry, it supports a softer treaty that emphasizes clean-up rather than production. The difference will likely come down to language; for a legally binding treaty, “parties shall” is a world away from “parties are encouraged to.” Stodal worries that the final compromise will fall short of the necessary change.

“It’s not enough to just impose a tax or encourage recycling,” he said. “It’s going to take a radical transformation of almost every industry.”

* * *

The boat’s round bow leapt over dark water, tossing long fins of white spray that burned salt through the mouth hole of my balaclava. It was the morning after the official event, and I, along with five journalists and UN Habitat employees, had donned neon survival suits and wedged into a black twelve-seater inflatable boat at Tromsø harbor. Led by Brage Heill, administrator at Salt and former coastal cleaner, we were speeding north up the sound to check out some local cleanup sites.

“It’s amazing what you find out here,” the bearded blonde Norwegian shouted over the roar of the motor, his eyes shining behind fogged horn-rimmed glasses. “We’re talking decades of stuff.”

Back ashore, Heill had shown us a color-coded map of Norway’s coastline. Cleaned sites were marked blue, still-to-clean sites purple. The uncleaned sites are concentrated around the north; they are the most logistically difficult and have the shortest cleanup season. Of course, “clean” is relative because the work never really ends: As long as the ocean moves, plastic will wind up back on the same shores. But, Heill says, repeat cleans are nothing like the first, excavating trash accumulated over more than a century of planetary plastic.

Over his two years as a coastal renovator, Heill became something of a waste archeologist, learning to trace the decades by materials’ thickness and quality. In a single day on some remote island, he found three generations of the same iconic Norwegian “Idunn” ketchup bottle: first glass, then thick plastic with the blocky branding recognizable from Heill’s childhood and finally the thinner, squeezable version you’d find on the shelf today. He has come across various products washed ashore from Asia, Russia, Europe and North America. But many more were merely seashell-like shards, split and smoothed into unidentifiable fragments. The teams don’t collect pieces smaller than two and a half centimeters. “We have to stop somewhere,” Heill said.

Each artifact tells a story, and some have been remarkable. On the coast of Svalbard—an archipelago halfway between Norway and the North Pole—one of his Salt co-workers found a message in a bottle (posteflaske), tossed from a Norwegian coastal city several hundred miles south more than 50 years ago. The employee got in touch with the man who threw it, who was delighted to find his message discovered.

After about 45 minutes, the waves grew too high to venture further. So we stopped within sight of a clutch of green islands at the mouth of the Norwegian Sea. Heill poured tea from a steaming thermos, and we huddled together, warming numb hands and steadying our cups against the rocking swells.

“That is one of our major cleanup sites,” Heill said, pointing north to a jutting green embankment lashed by violent breakers. Due to its exposed position, and the strength of westerly winds, he said, this site accumulated an outsized amount of litter. From a kilometer or so away, its pebbly beach seemed pristine. But even since the last time it was cleaned, that relentless pummeling has doubtless dispatched more of the world’s plastic.

Now that he’s an administrator, Heill spends most of his time behind a desk. On this morning, leaning into the wind, he spoke with nostalgia about long, freezing days and risky, tide-dependent moorings on shores as-yet untrodden by human feet. As I’ve mentioned, Arctic coastal cleanup is complicated and often dangerous, and requires rigorous training, specialized equipment and teamwork. In some cases, the sea is not the only source of danger. For expeditions to Svalbard, where polar bears outnumber people, the teams must bring a rifle aboard. Often, for big cleanup sites, they can’t sacrifice precious cargo space to seats, and the long ride home means huddling in the deck of the vessel between bouncing bags of trash.

As the winds rose and began whistling, we turned for home. Soon, the brief Arctic cleanup season would end. For the next few months, as ice rims this coast and the water blossoms with bergs, Salt researchers will continue to sort, analyze and source plastic gathered from its summer shores. At the same time, the globe’s nations will finalize a new vision for a seductively practical—but pernicious and pervasive—substance.

Heill has a healthy skepticism about his home country’s stated environmental priorities. Norway continues to aggressively pursue petroleum exploration and exports, and recently faced international backlash for controversial forays into deep-sea mining. But on plastic cleanup, he concedes, Norway seems to be getting something right. This country of only five million has shown that coastal clean-up isn’t just possible, it also doesn’t have to rely entirely on public funds or the generosity of volunteers.

And it is, quite simply, a great gig.

“You get to be out in environments you’d never see otherwise, doing something directly meaningful for them.” Heill said. He gestured around us, across the choppy dark water to the distant white peaks of the Malangen mountains. Just above, a faint half-rainbow shimmered against the gloom.

“This is a workday. Pretty unbelievable, right?”

Top photo: Brage Heill, administrator at the coastal non-profit Salt and former “coastal renovator” at Tromsø Harbor