AMSTERDAM — I heard Hans van den Hurk before I saw him, his 1996 750cc Honda motorcycle roaring down the quiet street of the hip De Pijp neighborhood where we were set to grab coffee. With coiffed white hair and a trimmed beard, he greeted with me a big grin and twinkle in his eye. He now leads psychedelic retreats across Europe but in 1993, he started the first “smartshop” in the Netherlands, selling magic mushrooms and other “brain foods” from an art gallery in central Amsterdam named Conscious Dreams. Our conversation started what became a monthlong trip through the Dutch legal psychedelic scene, culminating with me on a farm surrounded by hundreds of kilos of magic truffles.

On this journey, my goal was to learn about the how fungi carrying psilocybin—a naturally occurring compound produced by more than 200 species of fungi and consumed for their mind-altering effects—are used and regulated in the Netherlands. What lessons does the Dutch model provides for cities, states and countries looking for a path out of blanket criminalization of such drugs? Is it possible to safely sell psychedelic substances to the public? How do you set quality standards and controls? What are the risks and how can they be mitigated? Seeking answers to these questions, I spoke with entrepreneurs who started legally selling magic mushrooms and truffles in the Netherlands in the early 1990s about how the market got started, where it is today and what lessons they wish the government and others would learn from their experiences.

Psychoactive plants have been used for thousands of years by indigenous peoples around the world for spiritual and community-bonding reasons. In oversimplified terms, magic mushrooms were first popularly introduced to the West in 1957 with an article in LIFE magazine called “Seeking Magic Mushrooms: The Discovery of Mushrooms That Cause Strange Visions.” It described the experience of a vice president at J.P. Morgan tripping on magic mushrooms for the first time in Mexico. The main psychoactive ingredient, what makes these mushrooms “magic,” is psilocybin.

In 1958, a Swiss chemist isolated psilocybin. That led to thousands of scientific research papers about their potential for healing depression, anxiety and addiction. It was also used recreationally until 1968, when the cultural tide turned and the US government categorized psilocybin as a Schedule 1 drug, making it illegal. The United States also pressured the rest of the world to follow suit, ending the substance’s promising potential.

In the past two to three decades, however, psychedelic substances like psilocybin have seen a revival. The US Department of Veterans Affairs is now researching its potential to heal PTSD, and even the conservative Wall Street Journal has described beneficial psilocybin use among C-suite executives and working moms.

Back in the Netherlands of the early ’90s, the second summer of love was coming into bloom. In his late 20s, Hans was working in IT for IBM when he noticed the rise of MDMA, LSD and other drug use by his friends and younger siblings. Wanting to better understand the phenomenon and how to keep the people he cared about safe, he started volunteering with Adviesburo Drugs, a harm reduction non-profit launched by the pioneering harm reductionist August De Loor. As a volunteer, Hans set up testing services at rave parties where people could check the quality of their drugs. He also wrote reports on prevention and harm reduction requested by the government. But he wanted to do more to help users like his friends and family.

In a fateful decision, he determined that rather than testing drugs to ensure their safety, he would sell safe, legal substances himself directly to partygoers. In October 1993, he opened Conscious Dreams in central Amsterdam. “My idea was to not just tell people about drugs or do research but also to give advice on what to combine and what not to combine,” he said. “And if possible, sell them high-quality substances within the limits of the law.”

He sold herbal alternatives as well as synthetic substances chemically similar to popular drugs like MDMA. The shop was not successful during the first year until one day, a man on a bike showed up with some magic mushrooms containing psilocybin and asked if Hans would be interested in selling them. After checking with his lawyers, they discovered that while the chemical substance psilocybin was (and still is) illegal, mushrooms containing psilocybin were not. The Dutch Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) considered them agricultural products. The legality was grey, but facing at worst a fine or minor court case, Hans decided to take the risk. Seemingly overnight, he had a line out the door.

In 2002, the Supreme Court definitively ruled that fresh mushrooms did not fall under the Opium Act. A few years later in 2007, the Health Ministry conducted an overall risk assessment of magic mushrooms, concluding that “the physical and psychological dependence potential of magic mushrooms was low, that acute toxicity was moderate, chronic toxicity low and public health and criminal aspects negligible.” However, the conclusion also noted the use of magic mushrooms together with other substances such as alcohol deserved careful attention as did the importance of a person’s “set and setting” when taking them.

Set and setting refer to the state of mind—mindset—the person taking a substance is in and the environment—the “setting.” The term was popularized by Norman Zinberg in his influential 1986 book Drug, Set, and Setting.” In the context of the medical, therapeutic or recreational use of psychedelic substances, “set” refers to a person’s intentions prior to taking that substance. “Setting” includes everyone taking the drug together: in a park with close friends, for example, or a cozy room with a therapist. Cultivating proper set and setting are highly important for ensuring positive experiences even at low doses.

At its height, Hans’s “smartshop”—as stores selling psychoactive substances would come to be known—and his wholesale business employed over 20 people. The term smartshop was coined not by Hans but the media that used the term to describe shops in which magic mushrooms were sold because they also sold supposedly cognitive enhancing products such as lion’s mane and specialized teas. Hans made it clear that while he bordered the legal grey zone, he never sold substances that were patently illegal. He also openly discussed his activities with government officials at the Health and Justice ministries. During those conversations, he would beg them to create licensure requirements, quality controls and other measures to protect consumers and push out bad actors. But the government shied away from any meaningful rules beyond saying that a substance was or wasn’t legal to be sold.

Hans recalls his early days with some reverie as well as bitterness. “I worked in drug prevention before, so I tried to control the market,” he said. “Taking care only to hire personnel in the shop who knew what they were talking about—that’s very important. That’s why we also started an organization of smartshops with this philosophy (VLOS, 1997). But it’s a free market and the government didn’t help us. We asked for rules also in production, to have quality control and things like that. There was no reaction, it was: ‘It’s your problem, we don’t care.’ So it’s business. So you saw new companies popping up who didn’t share the safety concern.”

Hans’s worst fears came true in 2007 when a French tourist combined magic mushrooms she’d bought at an unscrupulous smartshop with alcohol and other drugs, and jumped off an Amsterdam canal bridge to her death. While it is not clear that the psilocybin mushrooms were the main cause of her fatal decision, the incident sparked an international row between France and the Netherlands that led to the Dutch government’s banning all forms of magic mushrooms in 2008.

Hans and other smartshop owners came together to discuss the demise of their industry. They realized the government had banned mushrooms that grow above ground but not truffles that develop underground. After clarifying the legality, Hans and his fellow smartshop owners started selling fresh magic truffles instead. The legal technicality revolved around the fact that truffles are the sclerotia of a fungus and not explicitly included in the legislation banning mushrooms.

Responding to my queries, TRIMBOS, a government funded think-tank on drug policy, stated that there have been some reports of health incidents in the past 16 years, but that the number is relatively low compared to other psychoactive substances. The majority of those incidents involved people misusing or combining truffles with other substances. However, most people who use truffles in the Netherlands do so in a responsible way and a controlled environment, which reduces the risk of serious incidents. Currently, TRIMBOS is not tracking any significant political or public opposition to the open sale of psilocybin truffles and there is no specific legislation being developed to reduce their availability.

Today, the production and sale of psilocybin truffles falls under general consumer protection laws, and the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority can conduct inspections to ensure truffles are free from harmful substances. But there are still no specific regulations or quality controls for the cultivation or production of truffles. It is up to smartshops and growers to take responsibility for the products they sell.

While smartshops were saved by luck, the tragic death of the French tourist is a lesson in the importance of crafting thoughtful regulation to ensure individual safety and public health, and avoid harmful incidents that turn the public and government against drug decriminalization. Just as there are regulations for the production and sale of alcohol and cigarettes, tomatoes and salad, establishing protocols makes sense for any consumable psychedelic substance.

Early on, Hans inspired fellow harm reductionists to sell high-quality products with safety foremost in mind. The first to run with his idea was Guy Boels, who opened the second smartshop in the Netherlands, this time in the southernmost city of Maastricht. By offering his customers meaningful psychedelic experiences with products of the highest quality, he says he hopes to enrich their lives with love and contribute to a better world. He referred to the results of important psilocybin studies conducted by Roland Griffiths, a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, as proof of the powerful positive effects psilocybin truffles can inspire in those who take them responsibly.

I met Guy at a “Support Don’t Punish” boat ride in Amsterdam, and later took the two-and-a-half-hour train ride to Maastricht for what ended up being a 10-hour discussion. While an avid user in his youth, he stopped consuming psychedelics after becoming a father 20 years ago. Now in his 50s, Guy has the zeal of an entrepreneur and a religious missionary.

He grew his initial establishment into three separate smartshops and a wholesale business. When I visited him, he brought me to his shop in downtown Maastricht, nestled between a hair salon and a women’s clothing store facing a restaurant terrace.

The non-descript storefront window showcases cannabis smoking accessories and herbal supplements. Inside, neatly ordered products line the walls and shelves between colorful signs warning “Ignore street dealers.” Customers can browse the aisles or look through a cannabis seed and magic truffle catalogue. A stickler for quality, Guy keeps his truffles in fridges behind the counter in small, branded plastic boxes—he believes vacuum-sealing or cutting them makes them less potent.

Guy holds himself and his team to a higher standard than the government requires because of his belief in ensuring positive experiences. His packaged truffles, also sold at other high-quality smartshops such as Kokopelli in Amsterdam, come in 10-gram and 15-gram cases. That represents a conscious harm-reduction choice because novices shouldn’t take more than 10 grams and even experienced users should calibrate their use. Every gram of truffle contains about a milligram of psilocybin.

While I was in the shop, some German tourists in their early 20s rushed inside, all bravado, asking for the “best” truffles. Guy’s staff calmly asked about their prior experience with psychedelics—they had none. After expounding on the need to not eat for two to three hours before consuming truffles and refrain from using other substances, and which settings may induce the best experiences, he suggested 10 grams of a mild truffle. “First take 7 grams, and if after two hours you think you can handle more, take the remaining 3 grams,” he instructed. Their quest accomplished, the three lads happily scurried outside with their loot.

Unlike alcohol and cocaine, which reliably provide similar effects under various conditions, the experience induced by psilocybin truffles are very dependent on the person and the set and setting in which they are taken. Many of Guy’s customers are students and tourists from neighboring countries. By embedding harm reduction in his sale he wants to make sure they do not take more than they can handle and do so in conditions that promote positive trips.

The interaction I witnessed is an example of responsible commercial actors acting within a harm reduction framework. “Less is more” is the driving mantra. At a less scrupulous shop, the lads could have been sold 15 or 20 grams of a powerful truffle that would have sent them unprepared into Alice’s wonderland in the name of maximizing profit. Still, under the current regulatory regime, the government treats both shops the same way, and both would be blamed for another fatal incident. A good argument, responsible sellers say, for thoughtful government regulation.

After spending the night in Maastricht and a morning visit to Guy’s warehouse, located down the street from a police station, I headed back north to Amsterdam. Looking out at the lush green farmland speeding by the train window, I knew I wanted to see for myself where truffles came from. Luckily for me, Hans knew exactly where to take me.

A few days later, he picked me up and we drove over an hour south of Amsterdam through pear and corn fields to Fresh Mushrooms farms to meet Hans Grootewal, who’s been openly growing magic mushrooms and truffles for the past 30 years.

At 82 years old, Hans G. is a G. In his youth, he built a high-tech dairy farm, but left it to become a consultant for other dairy farmers looking to modernize their operations. When he was 50, a friend told him about Hans van den Hurk’s Conscious Dreams art gallery, so he stopped by one day for some magic mushrooms. After a powerful psychedelic trip, he found his new vocation: growing high-quality magic mushrooms at scale. Hans was his first customer, and today he is considered the largest legal producer of magic truffles in the country if not the world.

An avid microdoser, he graciously opened his farm and operations to me, answering all my questions with a smile with Hans V. translating. Like Hans V. and Guy, Hans G. is an evangelist for magic truffles and the positive power they can have on people’s lives and the world. After initial pleasantries in his farm office, he brought me to the grow room where thousands of bags nurturing magic truffles lined the shelves at various stages of growth. I couldn’t believe my eyes. In the United States, Hans G. would be put behind bars for life for his large-scale production, and the authorities would probably have Hans V. and me sent to jail, too, just for good measure. But here we were, perfectly safe in a perfectly legal environment. I couldn’t help but laugh, “This is wild!”

Since the 2008 law banning mushrooms after the death of the French tourist, Fresh Mushrooms farm grows seven types of truffles including Atlantis, Tampanensis, Mexicana and Hollandia. Their names signify their origin—Atlanta, Georgia; Tampa, Florida; Mexico and Holland—where they were first discovered. After the switch to truffles, the growers discovered their product has more consistent amounts of psilocybin per truffle than mushrooms do, making them safer and more reliable. That is another point to keep in mind for regulators and businesses if psilocybin mushrooms and truffles are to be sold elsewhere in the future.

Hans G.’s wholesalers repackage, mix and match those seven truffle types into dozens of different branded boxes claiming varying degrees of strength, effects and potencies. Despite the variety of names, however, Hans G. knows they all originate from the same Stropharia Cubensis fungi family, so considers their differencesminimal. Nevertheless, other truffle growers may cultivate different varieties of which I am not aware.

After Hans G. showed me the cleaning and packaging processes, we sat back down at the farm office. He explained that with the help of 10 employees, many of whom are family members, his farm produces and sells a few hundred kilos a month. Hans G. sells only to Dutch-based wholesalers but estimates that 40 percent of his products are consumed in the Netherlands and 60 percent resold across Europe.

In recent years, the largest growth has come from the increasing demand for micro-dosing. The process involves taking a gram of truffles every third day consistently over long periods of time. While research on the effects is still limited, anecdotally it has received positive attention—including from The Wall Street Journal as noted earlier.

Hans G. packages his own micro-dosing kits. They are sold by his wholesalers who also repackage his truffles with their own packaging and branding. He sells the truffles in parcels of six 1-gram doses. It is important to him that his packaging clearly states that each dose should be taken only once every three days, along with health information in six languages. The reason for packaging only 6 grams at a time is preventing people from macro-dosing by consuming all the truffles at once.

His wholesalers are not as focused on safety, providing little information on their boxes. That could mislead customers into using daily or more than recommended. Unfortunately, here, too, there is no regulation and the government does not reward Hans G.’s good behavior or punish others’ bad behavior—another example of the need for thoughtful regulation. Both Hans V. and Hans G. wish the government would take a more active role.

The lack of regulations prompted responsible smartshop owners to come together as early as 1997 to set up VLOS, a trade association to discuss best practices and self-regulation. Under the leadership of Floris Moerkamp, the young and energetic executive director, VLOS does its best to educate new smartshop owners and set safety standards to reduce the possibility of harmful incidents. However, they have no enforcement mechanisms when their members decide to do their own thing, and not all smartshops are part of the group. Voluntary standards are, after all, only voluntary.

The open availability and de-facto legalization of psilocybin truffles has led to a growing demand for, and supply of, therapeutic psilocybin and other psychedelic retreats over the past 10 years. During ceremonies that can be conducted in a group or individually, lasting a weekend or spanning a whole week, participants take a high dose of truffles—usually considered to be over 30 grams, although it varies by person—under the supervision of a facilitator.

After one such ceremony, Luc Van Poelje, a Dutch Marine veteran and former corporate executive, quit everything to become a 1:1 facilitator with a focus on English speakers and helping with research on the impact on veterans. He screens people to make sure dosing is really right for them and helps them think through their intentions. For the session itself, he sets up a comfortable and relaxing setting and guides users through their trips. Afterward, he is available to assist users as they try to integrate the lessons they learned into their daily lives. He told me that he does the work because of the powerful positive transformation he experienced himself and observes in the people for whom he’s facilitated such experiences who come to him from around the world.

The founder of Liann, Floris does his best to educate facilitators like Luc about best practices such as proper screening of participants and preparation prior to a ceremony, and refraining from making unscientific health or medical claims. He is also actively engaging with the government in the event it tries to regulate the practice. Although the anecdotes I’ve heard from people who have facilitated and participated in such ceremonies are overwhelmingly positive, the experience is still the Wild West, and I’ve heard some bad stories as well.

Reflecting on my conversations with magic mushroom and truffle entrepreneurs, policy wonks and truffle enthusiasts, it’s clear the Dutch model of openly selling naturally grown psilocybin truffles works relatively well both ensuring fun for users and protecting public health. That seems mostly down to the hard work of Hans, Guy and other pioneering entrepreneurs whose backgrounds in harm reduction before becoming businessmen set the stage for responsible selling. While their founding philosophy continues to be influencing the smartshop industry because there is no license requirement for selling magic truffles, I’ve run across many tourist shops and other unspecialized stores selling magic truffles with little regard to harm reduction as they prioritize quick sales and profits.

Similarly to how US states adapted the Dutch example when it came to regulating cannabis production and sale, state and local governments should do the same with the regulation of psilocybin fungi. The implementation of thoughtful regulation must replace the criminalization regime currently in place.

Simple decriminalization does not by itself ensure safety for users or public health. The impulse to infuse psilocybin in gummies or chocolates must be balanced with the risk that those items may be attractive to children or could be unknowingly consumed with harmful consequences. For their part, Hans V., Guy and Hans G. believe that only fresh plant-based psilocybin products such as truffles should be sold. They fear that anything else would be treated like candy, become less safe and also lose some of the essence it has as a plant-based substance.

In a simply decriminalized and unregulated market, the government does not have the necessary guidelines and tools to ensure quality control, promote good actors and punish bad ones. While the number of harmful incidents with openly available psilocybin fungi in the Netherlands has been minimal, and the peer-reviewed medical journal The Lancet has determined psilocybin to be the least harmful substance compared to alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, MDMA and cocaine, it remains a powerful drug that can create deeply negative experiences when mishandled.

When it comes to the growing popular interest in psilocybin fungi, it seems the genie is out of the bottle. In 2023, 8 million Americans used psilocybin at least once, half of them micro-dosing, according to the RAND Corporation. It’s important that policymakers as well as responsible businesses promote thoughtful standards for providing the most fun and meaningful experiences for people using those substances while ensuring their safety and public health. The record shows that not doing so would lead to harmful incidents, bad press and a public backlash.

What does the Dutch magic truffle policy tell us about the Dutch? It continues to come down to their perspective that people have an inherent right to act as they please as long as their actions do not cause public disturbances.

A few people looking dazzled at a tree in the forest or cloud formations in a park, or enjoying some music in their bedrooms doesn’t rise to the level of requiring the authorities to abridge that right or expending precious law enforcement resources to curb its use. I do find it interesting, though, that the government does only half the job when it comes to overseeing the use of cannabis and magic truffles. It regulates parts of the industry while leaving others to market forces. Perhaps that, too, is Dutch. They are after all capitalists at heart.

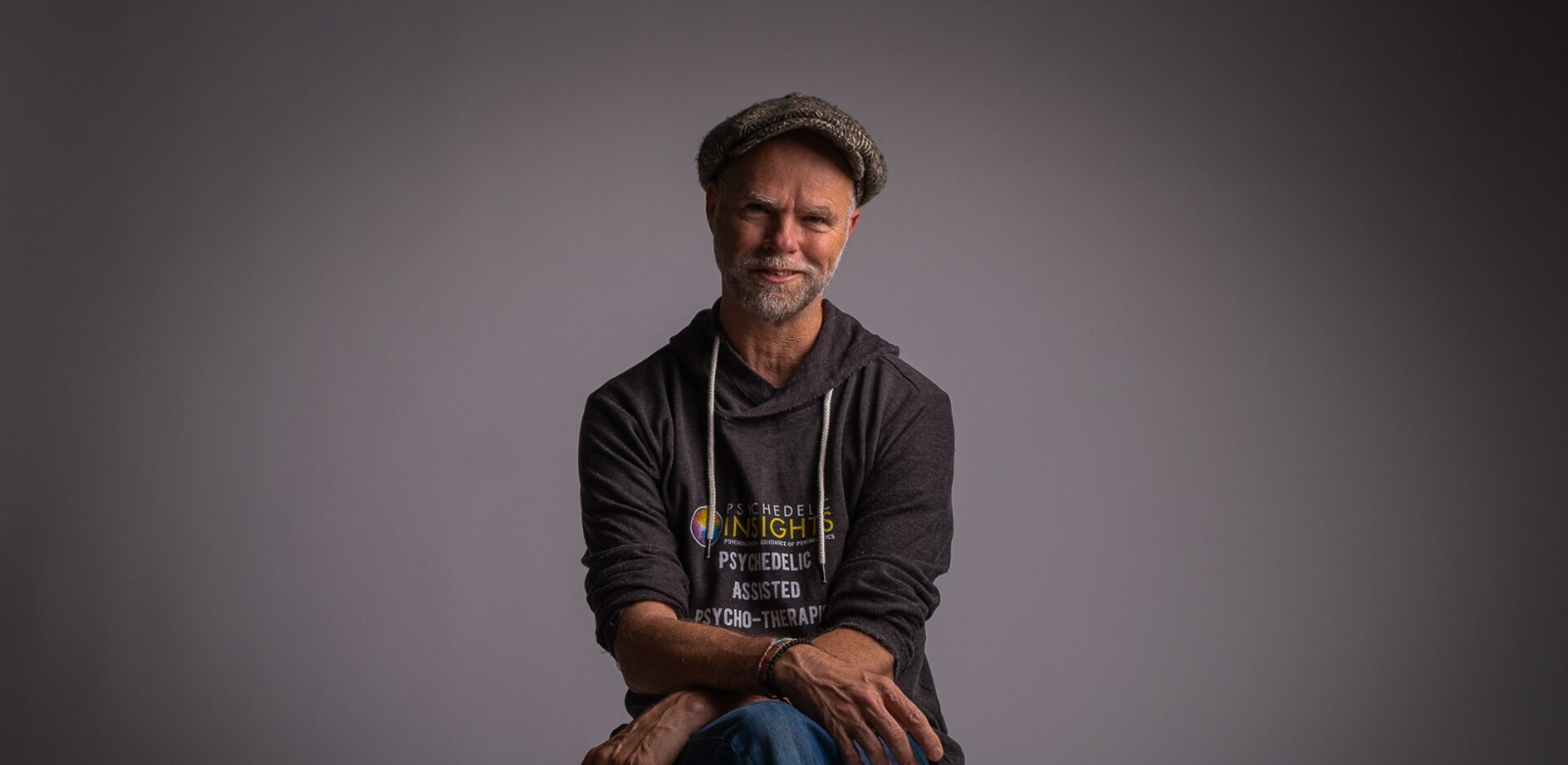

Top photo: Hans Grootewal and Rowland Robinson in the Fresh Mushroom Farm’s grow room