HERAKLION, Greece — At the end of June, friends from the Turkish cities of Izmir (formerly Smyrna) and Kuşadasi pinged my phone with dozens of photos, videos and social media posts from the Cretan Federation of Turkey’s 11th International Cretan Festival, a three-day event I didn’t expect to see in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey.

One video from Erol Gurman showed a delegation of Cretan musicians and dancers performing folk dances in traditional costume under the watchful image of Turkey’s founding father Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and the Turkish flag. The men dressed in black leather boots, navy blue vests and baggy, pleated breeches with fringed kerchiefs called saríkia wrapped around their heads and knives tucked into their belts. The women wore colorful pleated skirts and hand-woven aprons adorned with intricate patterns and long-sleeved vests embroidered with gold thread.

In another video shot in a large, open-air park, the costumed dancers were nearly lost in a crowd, thousands of people of all ages linking arms, dancing to the lute and lyra. And even though I currently live in Heraklion, the capital of Crete, I wish I could have been there to experience it.

The annual gathering of the federation’s 18 member associations from along the Anatolian coast features live music and dance, home-cooked Cretan dishes, film screenings, lectures and photo exhibitions. The festival is the biggest event of the year, a cultural touchstone for Turkey’s one million Turkocretans, Muslims whose ancestors emigrated from Crete to Anatolia either before or during a mandatory 1923 population exchange that displaced 1.3 million Orthodox Christians from Turkey and 400,000 Muslims from Greece.

The descendants of those refugees have one foot in Greece and one in Turkey, countries whose relations have been acrimonious and at times bloody. The two NATO allies have long argued over maritime and airspace boundaries, energy resources in the eastern Mediterranean, the demilitarization of islands and Turkey’s occupation of northern Cyprus. Following re-election, Erdogan and his new ministers continue to promote Turkey’s revisionist “Blue Homeland” doctrine that challenges the sovereignty of Greece and Cyprus.

Last November, while based on the Aegean island of Chios, I traveled across the narrow strait to Izmir to meet Turkocretans who had resettled in the neighborhoods of Bornova and Eşrefpaşa. Later, in Crete, I visited statues, exhibitions and associations commemorating the exchange and satisfied my sweet tooth at patisseries run by Anatolian Greeks. I learned that despite their religious differences, the descendants of the 1923 exchangees in Turkey and Greece understand the trauma of exile and the difficulty of rebuilding lives in foreign places. With a shared longing for their homelands and a desire to preserve their customs and traditions, they are uniquely positioned as a bridge between the two countries.

Visiting Turkocretan communities in Izmir

Ascending the stairs to the Eşrefpaşa Cretan Association, I didn’t know what to expect. Who would be there to meet me? Would we communicate in English or Greek? At the door, a group of third-generation Turkocretans welcomed me with Turkish tea and cookies. Two of the men wore prominent mustaches in the Cretan style. We sat in a circle, and since most of the members spoke Turkish, Erol Gurman, a smiling man in a dapper gray suit, sat beside me and translated what they said into halting English, sprinkling in some Greek words. He told me his family’s story, then answered my questions in consultation with the group.

Gurman’s family came to Heraklion from Anatolia about 350 years ago as part of the Ottoman force sent to wrest Crete from the Venetians during the Cretan War. After conquering the island, the sultan asked Gurman’s ancestors to stay on Crete and gave them farmland. At that time, 30 to 40 percent of the local population—higher than in any other part of the Greek world—converted to Islam, largely for socioeconomic benefits or via mixed marriages.

By the time of the Greek revolution some 150 years later in 1821, a growing national consciousness and evidence of the Ottoman Empire’s decline led the island’s Christians to agitate for union with Greece. Frequent uprisings strained relations with Crete’s Muslim population, who sought the empire’s protection. The 1878 Pact of Chalepa attempted to subdue the insurrections by expanding Christians’ rights and self-government.

After the pact granted Christians a majority in Crete’s General Assembly and preference for public posts like the gendarmerie, Gurman told me, the situation for Muslims on the island deteriorated. Violence escalated in the mountainous villages outside Chania and Heraklion. One association member said he lost 43 ancestors in the bloodshed.

Mehmet Soydan, a butcher who translated for me when I visited the Bornova Cretan Association, shared a similar story. “Christians killed my granddad’s father,” he said. “That’s why he ran away. After he settled down in Turkey, he never said anything about Crete. He didn’t want to talk about it. That’s why we don’t know much about what happened.”

Thousands of Muslims fled Crete for Ottoman domains in modern-day Turkey, Egypt, Libya, Syria and Lebanon between 1897 and 1899, during the final uprising that resulted in Crete’s becoming an autonomous state. The mass emigration during those years reduced the Muslim population by more than half, to 33,000 residents, or 10 percent of the total, by 1900.

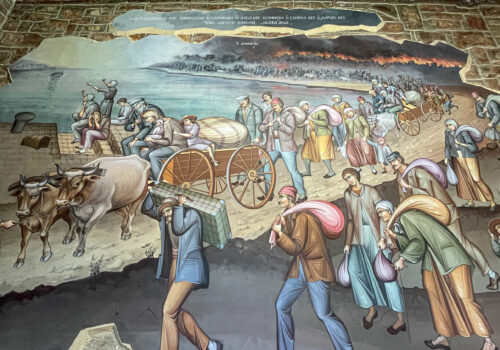

Gurman and Soydan’s ancestors, who escaped to Anatolia around 1900, refer to themselves as muhacirs, a Turkish word meaning “immigrants, refugees.” They brought little more than the clothes on their backs and perhaps a single wooden suitcase. They left any property they had behind and could not exchange it for land or real estate in Turkey like the mübadils, Muslims who came during the compulsory, government-facilitated 1923 population exchange. By then, the Muslim population on Crete had fallen to around 24,000, mostly living in the island’s cities.

After Turkey’s victory in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922, what Greeks call the Asia Minor Catastrophe, Greece and the newly formed state signed the 1923 Lausanne Convention Concerning the Exchange of Populations, setting in motion the largest displacement in modern history. Leaders of both countries wanted to create ethnically homogenous nation-states based on the European model, and religion was used as the defining criteria. So Muslims became Turks and Orthodox Christians became Greeks regardless of the language they spoke or how long they had lived on the opposite coast. Battle-weary Turkey also feared Greek irredentism, while Greece needed property for the refugees streaming into its borders from Anatolia.

As a result of the agreement, nearly 2 million people were forced from their homes and endured arduous journeys to unknown lands. Mustafa Sualp from the Bornova association told me his family members didn’t know where they were headed until they boarded a ship, and they were nearly separated. His grandfather was a tailor in Chania, and the family was given the choice of settling in either Çanakkale or Izmir. They handed over the deeds for 14 properties in Crete and were given a two-story house in Eşrefpaşa that had belonged to a Christian. At the Eşrefpaşa association, I had a chance to see some of the dresses, silverware and linens exchangees had brought with them.

The Memory House of Migration and Exchange in Izmir’s formerly Greek and Levantine suburb of Buca tells the story of the mübadils and muhacirs who resettled in Turkey. Housed in a 1904 residence of the Chios architectural style, the museum describes the “legendary” Gulcemal, a steamship used to transport Turkish exchangees across the Aegean and Black seas. It includes photographs and artifacts from the tahaffuzhanes, or quarantine stations where they were sent upon arrival. It also features testimonies about the lives they built in Turkey and how much they missed their homeland. A plaque in the courtyard connects the displaced communities. It reads, “The experiences during the exchange and migration formed a common memory and identity among the peoples living in both sides of the Aegean.”

The Turkocretans pursued similar professions in Anatolia. Many cultivated olive trees as their ancestors had in Crete. They grew fruits and vegetables in the farmland that once surrounded Bornova and brought skilled professions to the district, which had previously served as a summer residence for the wealthy. Soydan’s family worked as butchers in Heraklion and continued the profession in Bornova, opening a butcher shop there in 1925 that he still runs.

One of the biggest difficulties the exchangees faced upon arrival was learning the Turkish language, since Greek, particularly the Cretan dialect, was the language of daily life in Crete. Soydan’s aunts and uncles, now in their 90s, still speak Greek when they’re together. Like the Anatolian Greeks, they weren’t accepted by the locals because they came from a Christian place. Another problem they faced was economic. “They didn’t have money, land or business networks,” Soydan said. “They started from zero.”

The Bornova and Eşrefpaşa associations were founded in 2015 and 2017, respectively. Both groups meet in person once a week and maintain active Facebook pages, sharing birthdays, funeral announcements, photos and articles about Crete. In addition to the festival, they host panels, trips and conferences aiming to keep the Turkocretan culture alive for future generations.

Many of the members have visited Greece multiple times. Gurman, for one, has been to Crete twice and regularly messages with Greeks he has met through Greece-Turkey friendship and language exchange groups. He has been hosted by friends in Crete and repays the favor by showing them around when they visit Izmir. “I am a little bit famous in Crete,” he told me. Before I left, he connected me with several of his friends in Heraklion.

Traces of the population exchange on Crete

In early June, a few weeks before the Cretan festival, federation president Yunus Çengel traveled to Crete to promote the event, invite local officials and discuss potential collaborations. Along his journey, he also took pictures of various sites in Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion that served as mosques during the Ottoman period.

These buildings have complex histories. One structure in Chania’s old town was originally constructed as a double-aisled church during the Venetian period and converted into a mosque under the Ottomans. In the 20th century, it was used as a private residence and now operates as a lamp shop. The base of a minaret and a mihrab in the southeast corner of the building can still be seen, as well as 17 Venetian-era cist graves uncovered during a recent restoration.

Melis Cankara, an architect and postdoctoral researcher, examined how properties in the old town of Rethymno changed hands in 1923. She found that with the departure of the Muslim population, the use of certain buildings like mosques, hammams and medreses shifted. Today, most of those symbolic structures are used as cultural spaces. In addition, certain occupations worked primarily by Muslims like fez molding and horseshoeing became extinct after the exchange. Since many locals laid claim to Muslim properties before they were reassigned to refugees, the remaining properties were also subdivided to meet the needs of the new inhabitants.

In a video call, Cankara explained that while the exchange made Greece and Turkey religiously homogenous, it actually increased linguistic and ethnic diversity. On one street she studied, ownership after the exchange was divided between locals, refugees and Armenians who spoke the Cretan dialect, Greek and Armenian respectively. “The people who migrated from Anatolia had different backgrounds, different cultures,” she said. “Homogeneity was the purpose, but not the outcome.”

After my trip to Izmir, I also began to see signs of the population exchange everywhere on Crete. This year, in honor of the centenary, the regional and municipal governments mounted exhibits in Chania and Heraklion about the refugees who came to Crete after the catastrophe.

Some of the island’s best sweets are made by the descendants of exchangees. According to Iordanis Akasiadis, owner of the popular Chania bougatsa shop, the flaky phyllo dough pie filled with a slightly sour mizithra cheese and sprinkled with sugar is an Ottoman recipe taught to his great-grandfather in 1924 by a Muslim who sold him his oven before leaving the island.

In the old town of Rethymno, 88-year-old Giorgos Chatziparaschos, the descendant of Anatolian Greeks from Fokia, makes baklava and kataifi by hand. I’ve watched him throw phyllo dough billowing like a fresh sheet over the huge tables in his workshop, and I’ve been mesmerized by the enormous spinning copper disk that cooks batches of stringy kataifi. His crispy cubes of baklava remind me of the versions of the sweet I’ve savored in Istanbul and Izmir.

I’m spending the summer in the village of Epano Archanes just outside Heraklion, and every time I drive the 15 kilometers into town, I pass through the neighborhood of Nea Alatsata near the Minoan palace of Knossos. Formerly a Muslim neighborhood, it was resettled by Orthodox Christians from the village of Alatsata near Izmir.

In February, I visited the Association of Alatsatans of Heraklion Prefecture, which is housed in an old mosque, part of the Bektashi tekke of Ali Dede Horasani, a dervish lodge and place of worship founded at the beginning of the Ottoman siege of Heraklion in 1650. The association was first established in 1936 to provide mutual aid, food and medicine to Anatolian refugees. Some 29,000 arrived on the island, according to the 1923 census, and 45 percent settled in Heraklion. The club’s activity faded with the outbreak of World War II, but it was reestablished in 1982 with the aim of protecting Asia Minor customs and traditions that were quickly disappearing. Today, the association has 400 active members.

Christina Hatziadam, the current president, told me that for the Anatolian Greeks whose families were “persecuted with fire and iron” during the 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe, the centenary of the population exchange is a reminder of how traumatic and deeply unfair those years were.

“Both the refugees in Turkey and our refugees in Greece experienced rejection where they settled,” Hatziadam said. “We were called ‘tourkósporoi,’ or ‘Turk-spawn.’ They were called ‘Yunan,’ Turkish for ‘Greek.’ But at least they left peacefully and weren’t killed en masse like we were. Here, most of the refugee population was female. The men were held captive by the Turks. Those who survived came in 1923 with the exchange, or they didn’t come at all.”

On July 16, the association hosted its annual music and dance performance, dedicated this year to the Asia Minor woman and the 100th anniversary of the population exchange. It was held in an open-air theater between Heraklion’s fortress walls for an enthusiastic audience that clapped and sang along to many of the 25 traditional songs on the evening’s program.

Slowly, the exchangees in Crete and Anatolia integrated into their new communities and intermarried with the local population. Hatziadam, a third-generation refugee, married a Cretan from the southern village of Vori. She told me that while the first generation married almost exclusively among themselves, by her generation, marrying outside the community wasn’t an issue. Nevertheless, when her husband and his parents came to ask for her hand, her grandmother asked her mother, “Daughter, is he one of ours?”

Anatolian traditions gradually married Cretan ones. “In the kitchen, our peppers and spices complemented and enriched the Cretan cuisine,” Hatziadam said. “Many Cretans say they like the food made by their Smyrniot and Alatsatan neighbors and learned to cook their recipes.”

Yunus Çengel, the Cretan Federation of Turkey president, emphasized the similarities between the Turkocretans and Cretans today. The only difference, he insisted, is that a Muslim goes to a mosque and a Christian goes to a church. “But we believe in the same God,” he told me. “We speak the same language, eat the same food. Same music, same dance. All together, we are the same.”

In general, the Turkocretans I met viewed themselves as European Turks. They showed great respect for Eleftherios Venizelos, the Greek politician from Crete who sought to consolidate all the territory occupied by Greek speakers within the Greek state and negotiated the 1923 population exchange. After the exchange, he normalized relations between the two countries. He visited Turkey in 1930 and nominated Atatürk for the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize.

“We don’t see the Greek people or government as enemies,” Erol Gurman stressed. “Never.” The sentiment, delivered as tensions between the countries ran high during the pre-election period this past fall, gave me hope that there might be grassroots support in Turkey for improved relations.

President Erdogan and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis agreed to resume talks and confidence-building measures at the NATO summit in Vilnius in July, the culmination of a months-long period of calm. As partners like the United States emphasize the importance of stability in the eastern Mediterranean, I believe that the millions whose families were affected by the population exchange could offer the two countries a way forward.

Top photo: Mehmet Soydan and Hakan Gülen, president of the Bornova Cretan Association, outside Soydan’s butcher shop, which his family opened in 1925