Unguja ni njema atakaye aje — Zanzibar is good to those who will come, Swahili proverb

I approached the passenger side door with my bag slung over my shoulder, dripping with sweat as I waited for the taxi driver to unlock the car. As I stood there, wondering what might be taking so long, I saw that the driver was himself waiting patiently behind me — I was standing at the driver’s side. I had just landed in Zanzibar, and was discovering they use right-hand driving cars here. I walked around to the other side as the driver, Abdul, was tossing large papayas onto the back seat, each of which bounced off and rolled behind our feet.

I had to leave Oman in order for my visa to be finalized. Fortunately, this is the final step before I can return to Muscat and rejoin Emily as a fully-fledged resident of the Sultanate — but it could take weeks for my application to be processed and approved. So, seeking to make lemonade from a lemon, I decided to spend my time in Oman’s long time outpost and sometime capital: Mji Mkongwe,[i] or Stone Town, Zanzibar. Though separated by over 4,000 kilometers of open ocean, seasonal monsoon winds have connected the people of Oman and Zanzibar for centuries, and the age old bond between the two remains in manifold ways.

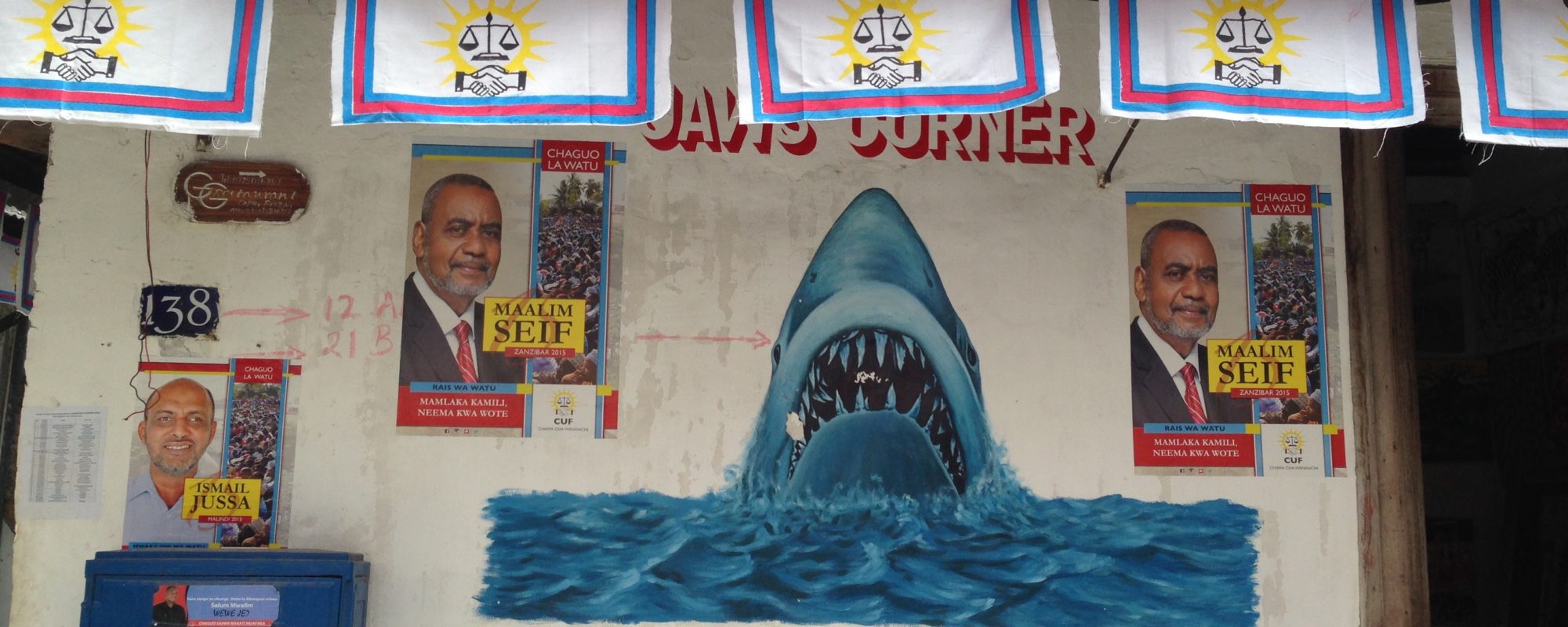

As Abdul and I zipped past corrugated tin shacks and roadside fruit stands on the road to Stone Town, he turned up the radio and rolled down the windows, letting in a humid breeze. He was wearing a vibrant red, white, and blue polo and a matching hat, both of which had CUF stitched onto them in block letters. On his hat was an image of a smiling man with RAISI WA WATU written under his chin — Swahili for “President of the People.” The man is Maalim Seif Sherif Hamad, Zanzibar presidential hopeful and longtime leader of the main opposition party on the islands, the Civic United Front, or CUF. The election this month is being seen as a referendum on the ruling Revolutionary Party, Chama cha Mapinduzi, or CCM, which has strong ties to the Tanzanian mainland.

The Zanzibar archipelago is a semi-autonomous region with its own president, but the islands have largely struggled since the 1964 revolution that ousted the Omani al Busaidi dynasty and installed a government inspired by mainland African nationalist and socialist movements. Shortly after the revolution, then-Tanganyika merged with the islands of the Zanzibar archipelago to create Tanzania;[ii] but in the decades hence, many Zanzibaris have found themselves desiring more autonomy from what they see as an economically unjust and politically out-of-touch mainland. This month, the air was pregnant with nervous anticipation in Stone Town, as several previous elections in Zanzibar have been marred by bombings and inter-party violence. On my first day on the islands, an ominous chalkboard sign in the heart of CUF territory in Stone Town read, “The Union’s days are numbered. 14 days remain. Please prepare yourselves. People power.” Hopefully, I would be back in Oman by then.

Speaking Swahili in Muscat

When I was last in Muscat as a part of a study abroad program, I signed up to stay with an Omani host family with the hope of mastering Arabic. I hadn’t even unpacked my bags when I noticed they were mainly speaking Swahili, peppering their conversations with an occasional Arabic and English phrase. My peers related similar experiences the next day in class, and lamented that they came “halfway across the world” to learn Arabic, not Swahili. Meanwhile, I was captivated by the idea that some Omanis spoke Swahili as a first language, and began what has become a years-long quest to better understand mobile histories, cultures, and identities in Oman, East Africa, and the greater Indian Ocean.

Some estimates place the numbers of Omanis with ties to the Swahili Coast at 20 percent or more of the population, although no official census or immigration records are available to the public. The Swahili and Zanzibari Omani community is extremely diverse — centuries of trickling migration between the Arabian Peninsula and Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, the Comoros, Zanzibar, and as far inland as Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi resulted in intermarriage, generational linguistic differences, and varying degrees of local assimilation. Distinctions within the community include variables such as tribal origins in Oman, date of arrival in East Africa (with early arrival being more prestigious), occupation, and the presence or lack of slaves in one’s family tree. An entire segment of citizens in Oman are descended solely from slaves, considered distinct from the more elite and mobile merchant Swahili and Zanzibari Omanis. Scholar Marc Valeri summarizes the sometimes-contradictory notions of identity within the entire community with ties to Africa this way: “Families, or even individuals, descended from the same clan can be considered ‘Swahili’ (or not) whether they have ties (or not) to Africa.”[iii] In other words, the terms Swahili or Zanzibari can be arbitrary labels, based on narratives rather than actual ties.

Swahili and Zanzibari Omanis have played an integral role in developing Oman and often occupy positions of influence and power in government and business. The current Grand Mufti of Oman and Minister of Education, for example, were born in Zanzibar and “returned” to Oman as members of a slow but large-scale migration out of East Africa by Omanis and other Arabs. The migration was triggered in part by the chaos and ethnic cleansing that followed the 1964 Zanzibar Revolution, and in part by the promise of a comfortable life and good pay in one’s ancestral homeland. These migrations are merely the latest swing of the pendulum between the Arabian Peninsula and Africa that has been oscillating for millennia.

In his first radio address as monarch in 1970, His Majesty Sultan Qaboos appealed to his countrymen for help in bringing prosperity and progress to Oman, but he also called out to those across the world with Omani roots:

Now, to our brothers who were forced out of the homeland by the unfortunate conditions of the past, and those who remained loyal to their homeland, but chose to remain abroad: you will soon be able to heed our call to serve your homeland; and to those who were not loyal to my father in the past, I say “let bygones be bygones, let bygones be bygones.” We call those of you with Omani nationality[iv] to return to ranks of unity in the Sultanate of Oman… We hope that you will be able to quickly return to your homeland and gather with your loved ones freely in peace and loyalty to your dear country.

In the subsequent decade, thousands heeded this call and “returned” to a country many of them had not yet visited, creating a segment of what Valeri has called the “demographic legacy of the Omani maritime empire.”[v] As long as one could prove Omani ancestry through their paternal bloodline, citizenship was granted in accordance with the relaxed immigration policy directed by His Majesty, at a time when the fledgling Sultanate was in desperate need of manpower. Many Swahili and Zanzibari Omanis who had left East Africa in the mid-1960s were not allowed into Oman by Sultan Qaboos’ father, and had started lives in Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia when His Majesty came to power. In addition to East African returnees that spoke Swahili, French, and English, a number of Baluch from southern Pakistan/Iran and Khojas from Gujarat also “returned,” joining their distant relatives in extant communities of Muscat. A unifying sense of “Omanity,” as Valeri has called it, is the thread that binds them together: the wearing of Omani national dress, the use of Arabic as a lingua franca, and fervent dedication to the Sultanate are just a few examples of how these diverse communities have rallied under a nebulous sense of “Omanity” to create a unified society.

Historical Omani Mobility in East Africa

Oman and East Africa are uniquely bound by shared history, language, culture, and ancient familial ties. Their connection is one of the oldest and strongest transcontinental networks in the Indian Ocean: in antiquity, Greek explorers recorded the presence of sailors from the southern and eastern Arabia Peninsula (present-day Oman and Yemen) along the East African coast. Often called the “Swahili coast” for the language spoken in southern coastal Somalia, Kenya and Tanzania, the word Swahili itself is derived from the Arabic sawahil, meaning “coasts.” Folklore places the arrival of Omanis in East Africa with the flight of two brothers, Suleiman and Said, from the Umayyad invasion of Oman in the 7th century C.E. They fled to Zanzibar, “land of blacks,” zanj being the old Perso-Arabic word for “black,” and bar for “coast.” Scholar Wendell Phillips refers to Arab migrants to Zanzibar and the rest of the Swahili coast over the subsequent centuries until the modern period as “Omani empire-builders” — trade and intermarriage flourished between the Arab visitors and Africans, laying the foundation for what would become a period of Omani domination of East Africa.[vi]

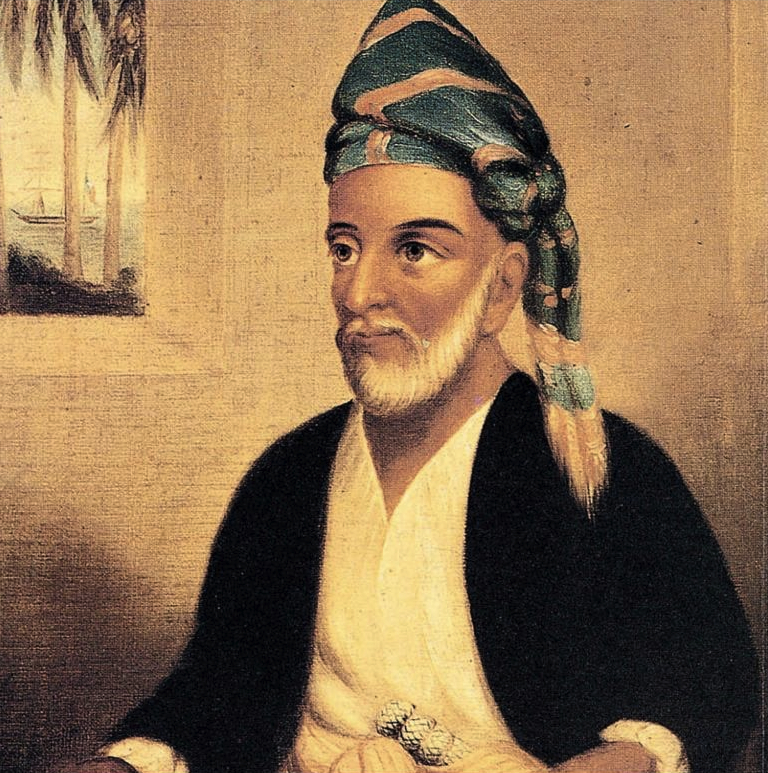

Members of the al Busaidi dynasty, who have ruled Oman since the mid-18th century, have always been highly mobile, spending seasons alternately in Muscat, Bombay, Mogadishu, Gwadar, Dar es Salaam, and other harbors along the Indian Ocean littoral. In the year 1832, Sultan Seyyid Said bin Sultan or “Said the Great,” set sail from Muscat harbor bound for Zanzibar, then one of the Sultanate’s many port dominions along the coasts of the western Indian Ocean. But the Sultan’s royal ship was not leaving Muscat for an ordinary winter retreat — he was moving his capital and seat of government from Muscat to Zanzibar, a pivotal moment in the converging histories of Oman and East Africa. His arrival cemented Zanzibar’s place as a center of trade, power, and culture that would last throughout and beyond the subsequent century.

During and after Said the Great’s reign, the floodgates were opened to Omanis from all strata of society, who plied the waters of the Indian Ocean for the promise of a better life. Some had small businesses, loading single ships with frankincense, dates, and dried fish from Oman to sell along the Swahili coast, returning to Muscat with ivory, spices, and dried coconut. Seasonal workers hitched a ride to Zanzibar as deckhands in the fall and winter, stayed for the clove harvest, and returned to Oman in the spring and summer for the date harvest. Others yet left for East Africa and chose to stay as merchants, plantation owners, or found positions in the Sultan’s government, later sending for their family to join in the tropical paradise of the Swahili coast.

The dynasty that preceded the al Busaidi managed to dent European colonial ambition in East Africa, but it was Said the Great who earned the reputation of ejecting the reviled Portuguese from the Swahili coast once and for all, relegating them to Mozambique and Madagascar. Under Sultan Said, trade in the western Indian Ocean boomed, with Arab noblesse, Indian merchants, laborers and other economic opportunists of all ethnicities leaving their homes for the many ports of Swahili coast. The most lucrative sources of revenue were cloves, ivory, mangrove poles, and the grimmest commodity of all: slaves. Both Omanis and Zanzibaris hail Sultan Said for halting the slave trade, and for solidifying Zanzibar’s status as a closer set of “spice islands” than the Dutch East Indies, but “quarantining” the slave trade might be a more accurate description. Said the Great forbade his subjects from selling slaves to the European powers, and from transporting slaves to Oman — but it was his successors who finally scrubbed the specter of slavery from the islands under the British in the late 19th century.

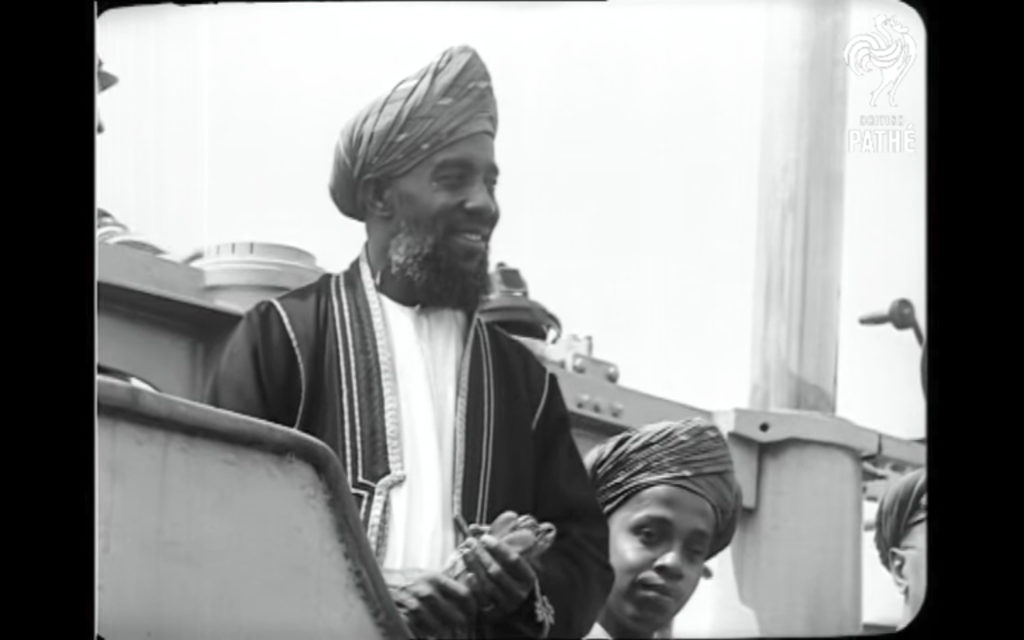

After Sultan Said’s death in 1856, his sons disagreed over succession, and the al Busaidi dynasty branched in two different directions — with one son accepting control over Muscat and Oman, and another over Zanzibar and East Africa. The conflict was mediated by Lord Canning, the British Viceroy of India, who hoped to (and did) cozy up to the Zanzibari wing of the dynasty for the gain of the Empire. The fracture had little effect, however, on the mobility of the thousands of Omanis that continued to sail to and from the islands of Zanzibar.

After the split, the two dominions of the al Busaidi developed in dramatically different ways. The Sultanate of Muscat and Oman faded into obscurity, feeling jilted by the British and suffering the financial impact of losing its most precious and successful foreign port. Religious and tribal wars plagued the al Busaidi sultans in Oman throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries.[vii] Those who could afford to leave Oman set their eyes on Zanzibar to cash in on the spice trade, further perpetuating Oman’s period of darkness by creating a brain drain. Omani and Arab migrants to East Africa had a built-in connection to the ruling elite in Zanzibar, and could easily coalesce with spheres of political and economic power. Zanzibar became the place where a deckhand could dream of earning riches — a land of opportunity. Lower and middle class Omanis could support families and businesses back in Oman by making seasonal trips to Africa.

In the years leading up to World War I, the British increased their influence on the islands, eventually incorporating Zanzibar as a protectorate of the Empire. The al Busaidis had no choice but to capitulate, retaining their titles but allowing all decisions of consequence to be made by the British resident. During this time, Zanzibar began its decline as a place of promise and plenty as the British focused on bolstering their holdings in mainland British East Africa, keeping the Zanzibar Sultanate in power to hedge German imperial aspirations in the region. Though the sovereignty of the al Busaidi in Zanzibar was compromised in part, Omani families that had settled in Zanzibar continued to hold a great deal of financial and political power as members of the elite. Today, many Omanis remember the reign of Seyyid Khalifa bin Haroub (r. 1911-1960) as the “golden age” of the Zanzibar Sultanate, despite having ruled at the apex of British influence.

Race and Revolution

In 1963, Britain abruptly discontinued Zanzibar’s status as a protectorate, and sovereignty of the Sultanate was briefly restored under Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah, albeit with an elected parliament. Meanwhile, many successful pan-African anticolonial movements had sprouted up across the continent, and some saw an opportunity to rid Zanzibar of its “imperial” and “Arab” monarchical government. The arbitrary distinctions between “African” and “Arab” gained momentum and political utility in the period leading up to independence, but the distinction was not, and is not today based on “blackness” or native tongue, but instead on a combination of paternal lineage, narrative generational history, and association (for example: an individual with primarily African blood could be accused of being ustaarabu, “striving to be Arab,” by adopting Arab dress, customs, and social networks). As with varied distinctions within the Swahili and Zanzibari Omani community noted earlier, the construct of race in Zanzibar is complex, and I hope to explore some of the nuances in both communities in future Newsletters.

As the fledgling Zanzibari parliament was taking shape in the early 1960’s, various ethnically-aligned social groups like the Arab Association, African Association, and Shirazi Association became nascent political parties that bore violent outcomes in the ensuing post-independence years. Racially charged language dominated the newspapers in Zanzibar throughout the 60’s, precipitating the violence that would occur during the revolution, which largely fell along dated and obscure constructions of race.

Discerning what “really happened” during the revolution is a difficult task for an outsider, as each side has its own narrative of the revolution’s motivations and aftermath. For a time, discourse was dominated by the African nationalists and supplemented by Western academics sympathetic to anti-colonial movements. Now, in a series of books in Arabic, Swahili, and English, Omanis are beginning to revise what they perceive to be an unjust history. They see historical portrayals of Arabs in the Western and mainland African imaginations as inaccurate; to them, the caricature of a crooked Arab slave trader was created and perpetuated by European colonial powers, forever enemies to Islamic ambition and success.

Both sides agree that some degree of violence occurred during the revolution. For the revolutionary party, the deaths have been downplayed over the years, and acknowledged only as an unfortunate byproduct of political upheaval. On the other hand, for families of Omani heritage living on the island, the violence is remembered as genocide — a stain on the charmed history of their beloved Zanzibar.

When the revolution began on January 12, 1964, a man named Field Marshall John Okello began a campaign of widespread anti-Arab violence that plunged the islands into chaos. Race-based rhetoric over the radio and newspapers reached a fever pitch, with Okello calling to rid the entire island of “slave-trader” and “imperialist” Arabs. Most of the violence now lives only in the memories of Zanzibari Omanis who witnessed it first-hand. Many Omani memoirs and histories of the islands choose not to reopen the still fresh wounds, describing their painful memories as “too terrible for words.”[viii] One author, Nasser Abdulla Al Riyami, provides graphic descriptions of the atrocities in the chapter “Ethnic Cleansing (The Massacre of the Century)” of his book Zanzibar: Personalities and Events 1828-1972. He describes Arabs being rounded up and tortured, dragged from cars, raped, dismembered, immolated, or forced to dig their own graves before execution. Building a consensus about how many Arabs were killed is difficult, but low estimates say a couple thousand, and the higher ranges say around a fifth of the Arab population, or 17,000 people.[ix]

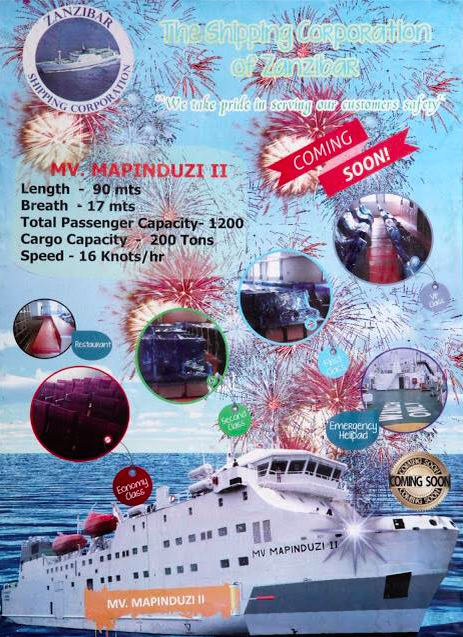

Although taboo to discuss in public, conversations about the revolution still play out behind closed doors in Oman, and are beginning to reenter semi-public forums like Facebook. On October 11th, someone posted a picture in the popular group “Zanzibar & Oman” of a new ferry named MV Mapinduzi II, which is scheduled to run between the two main islands of Zanzibar, Unguja and Pemba. In the comments section of the picture, users expressed varying degrees of outrage over the name of the ferry, which means “Revolution” in Swahili. One commenter wrote [all sic] “…my father was murder that day infront of our eyes… forgive but we will never forget.”

The only visual documentation of the violence was captured by Italian directors Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi for their 1966 shockumentary Africa Addio. Footage was shot from the air over two days, and condensed into a few minutes that made it into the final cut of the movie. The clips have taken on a mythic quality for Omanis and other Zanzibari Arabs, and have been spliced and reproduced on YouTube with Arabic narration, and printed as freeze frames in the Omani histories of the revolution, a tangible validation of their painful memories.

Chilling footage shows long lines of men marching toward the firing squad, groups of people sitting huddled in a circle waiting to be executed, and piles of bodies in a hastily dug mass grave. Through the haze of smoke, the smoldering remains of an entire village can be seen, with corpses splayed beside the charred homes. Another shot shows men, women, and children running into the receding tide, trying to climb aboard fishing boats; the next day’s footage shows the same spot, with the same people now lifeless and gunned down, their bodies floating along the shore. The Italians’ helicopter followed trucks full of dead bodies wearing dishdasha, or the traditional Omani dress, that were being transported and dumped into pits. Weeks later, when British filmmakers were allowed in, there were no mass graves photographed, and the bodies had been buried — just an interview with the revolutionary government, and images of plain-clothed men holding AK-47s in front of the Sultan’s palace.

Muscat and Stone Town in the 21st Century

Today, the Sultan’s former palace sits quietly in a state of decay. The Serikali ya Mapinduzi ya Zanzibar (SMZ), or Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar, appropriated all land belonging to the Sultanate as property of the revolution, along with many houses of non-royal Arab merchants and residents of the island. Most of the houses were ‘given to the people’ and divided into public housing, while other royal buildings became offices of the revolutionary government. For decades, the SMZ’s headquarters was one of the former Sultan’s largest palaces, called the House of Wonders for its plumbing and electricity in an era when the rest of the island had none. The SMZ has since moved elsewhere and it remains a shuttered museum. The final Sultan’s palace is filled with priceless antiques, oil paintings of the Sultans, and original fixtures, all of which collect dust in a museum run by the government. Paint peels off the walls in large chunks, and the first president of the revolutionary government’s portrait hangs prominently near the entrance.

Poignantly, in the royal court room, the Victorian rattan cane chairs that were a gift from the people of France have SMZ hastily hand-lettered in bright blue paint on the back. My government tour guide in the museum, who wore a starched short-sleeve button down and dark sunglasses indoors, was irreverent and eager to tell me about the practice of concubinage among al Busaidi sultans, pointing at various grand oil paintings saying “This one’s mother was a Russian slave, this one’s mother was an Ethiopian slave,” and going down the line. To enthusiastic members the Revolutionary Government, Omani rule is ancient history: feudal, racist, and oppressive.

In an antique china cabinet in the museum filled with books, stickers, and pins, I purchased a book called Zanzibar: The 1964 Revolution: Achievements and Prospects. On the first page, author Omar Mapuri says that the book has “been prompted by the proliferation of versions of the story of the Zanzibar Revolution, some of which contain significant distortions and confusion of the truth.” He goes on to call the massacres of Arabs “an unfortunate overstatement.”

“Some Revolution stories have been passed from parent to child among Zanzibari Arabs alleging that there were mass killings of Arabs during the Revolution… These stories are aimed at sustaining racial sentiments, and thus instilling hatred and a retributive stance among Arabs against Africans… Younger generations of Zanzibaris must be made aware of these distortions, lest all attempts toward bringing about racial harmony prove futile. Racial harmony can only be achieved in an atmosphere of equality and mutual respect between the races.”[x] Considering that the author attempts to flatly delegitimize what is a painful reality for thousands people, it is no wonder “racial harmony” is still something being sought by the Revolution.

Despite this rhetoric, today, most Zanzibaris seem ambivalent about Oman and “the Arabs,” if not eager to welcome them back. In one of the memoir-histories written by a Zanzibari Omani, the author shares a story of an old woman rebuking an SMZ official, saying “Where are those Arabs? When will they come back? I hope that they should come back as soon as possible. Under the Arabs, we had a good life, and got whatever we wanted. There were no human rights abuses, and no rations. What do we see now? Just hardship,” to the applause of others.[xi] CUF, the opposition political party that is expected to win this month if the polls are fair, has been accused of having Gulf backers, wanting to restore the Sultanate, and trying to bring the last Sultan (who is still living) back from exile in the UK.[xii] While the return of the Sultanate seems far-fetched, the CUF has indeed shown signs of reconciliation and acceptance of the island’s Omani history. Maalim Seif, CUF’s presidential candidate whose face is plastered walls, shirts and hats across Zanzibar, has publicly expressed remorse over anti-Arab violence during the revolution, and personal shame for the atrocities committed in his presence.

Even the SMZ has begun to eat humble pie, recently creating a website encouraging diaspora Zanzibaris to (re)invest in the islands, saying “evidence suggests that diasporas play a critical role in supporting sustainable development by transferring resources, knowledge, and ideas back to their home countries, and by integrating their countries of origins into the global economy.” Just as His Majesty Sultan Qaboos relied on educated and experienced diaspora Omanis living in Zanzibar to develop Oman, so now is the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar begging the people it once sought to eradicate restore their homeland’s former glory. The poetic justice of this appeal is not lost on Swahili and Zanzibari Omanis, many of whom are eager to connect with their beloved former home and see it flourish again.

In addition, the Omani government has slowly but steadily increased its investments in East Africa over the years, with joint projects aimed primarily at education, cultural heritage, and architectural preservation. The desire for even greater economic ties with East Africa is reawakening, especially in light of financial involvement from Chinese investors across the continent. Just this month, the Omani Minister of Transport and Communications broke ground on a colossal new port project and economic zone in Bagamoyo, an infamous former slave-trading outpost on mainland Tanzania just across the Zanzibar Channel. In the photo op, the Omani minister wears a flowing brown bisht over his disdasha, dressed like Omani gentry of old, holding a shovel beside his counterpart from the Tanzanian government and requisite Chinese investor, both in business suits.

Even at the micro level, Oman and the Gulf are the new lands of opportunity for residents of Zanzibar and East Africa. Just as sailors from the Oman once set out for Zanzibar in search of prosperity, the pendulum has swung in the other direction, with young Zanzibaris taking the direct Oman Air flight to Muscat with entrepreneurial spirits and dreams of success. And just as there were built-in connections to the ruling elite for the seasonal Omani visitors to Zanzibar, so now are there wide resources and vast networks for Zanzibaris in Oman. My guide’s brother in Stone Town works three months on, three months off in the oil fields of Oman for the Petroleum Development Oman, the state-owned oil company. When I asked if it was difficult for his brother to be away from home for so long, he said it wasn’t, adding, “we have a lot of cousins there.”

The ebb and flow of Omanis and East Africans across the Indian Ocean did not begin with Said the Great’s move to Zanzibar or end with the 1964 Revolution or the “return” of Swahili Omanis to Muscat. These events are merely markers of the beginnings and ends of eras in which the idea of “home” was more resolute for Swahili and Zanzibari Omanis whose histories and families exist somewhere between the two continents. Once seen as “diaspora Omanis” while living in Zanzibar, they are now “diaspora Zanzibaris” living in Oman. Nationality, identity, and “home,” are limiting words that make it impossible for the generations of migrants back and forth to be one or the other. The destinies of the people of Zanzibar and Oman are intertwined, and intersect despite misgivings on both sides of their histories. In the comments section of the Facebook post about Mapinduzi II, the new ferry in Zanzibar, one user wrote “all of us are victims of the ‘64 massacre. Omanis and Zanzibaris were affected in one-way or the other. It’s been 51 years now. And there is a ray of hope. Lets unite and be one. Our future looks bright.”

I am back in Muscat now, with my visa paperwork finally resolved, alhamdullilah. I returned just before the election, and despite the ominous sign I saw in Stone Town on my first day in Zanzibar, the election was peaceful and largely without major issues. After the polls closed, CUF’s Maalim Seif called on journalists and international observers to “respect the will of the people,” and defend his inevitable victory. The incumbent party, however, had other plans: the military stormed the Zanzibar Election Commission two days after the election, barring reporters and observers from entering for several hours. Shortly thereafter, the election results were annulled, due to allegations of vote tampering in Pemba, where CUF has widespread support. The election remains unresolved at the time of writing, but many expect a runoff in November.

Since I’ve been gone, a new store has opened on the ground floor of our apartment building in Muscat, called simply “Sale of Vegetables and Fruits.” The storefront has no decoration except for a string of flashing LED lights, and a single message on the window, written in Arabic and English: SWAHILI FOOD IS AVAILABLE.

[i] Mji Mkongwe translates as “Old Town” from Swahili, but the English Stone Town is more common

[ii] “Tan-” for Tanganyika, “-zan-” for Zanzibar, and “-ia” from Azania, the ancient Greek name for the western Indian Ocean

[iii] Marc Valeri, Oman: Politics and Society in the Qaboos State, p. 21

[iv] The Arabic jansiyya, in this context, means Omani tribal ancestry or parentage, not “nationality” in the strict sense of a naturalized citizen of Oman

[v] Marc Valeri, Oman: Politics and Society in the Qaboos State, p. 19.

[vi] Wendell Phillips, Oman: A History, p. 24.

[vii] When Sultan Qaboos said “let bygones be bygones” in his aforementioned 1970 radio address, he was in part referring Omanis who had opposed his father, or were resentful toward al Busaidi leadership in Oman, all of whom were welcomed back. The need to build a modern Sultanate surpassed tribal or nationalistic grudges.

[viii] Issa bin Nasser al Ismaily, Will Zanzibar Regain Her Past Prosperity?, p. xiv

[ix] Nasser Abdulla Al Riyami, Zanzibar: Personalities and Events 1828-1972, p. 204 and Marc Valeri, Oman: Politics and Society in the Qaboos State, p. 20

[x] Omar Mapuri, Zanzibar: The 1964 Revolution: Achievements and Prospects, p. 1

[xi] Issa bin Nasser Al Ismaily, Will Zanzibar Regain Her Past Prosperity?, p. 310

[xii] The Economist, October 21, 2015 “Why tensions are rising in Zanzibar”