BELGRADE — Its concrete and steel entrails exposed, the former headquarters of Yugoslavia’s Defense Ministry has ominously stood in ruins for over three decades in the capital’s administrative district. While recent reports suggest that—by some strange turn of events—former US President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, may have plans to turn the building into a luxury compound, the Serbian authorities have preserved it in its damaged state as a memorial to the city’s 1999 bombing by NATO forces.

The concrete carcass, as well as graffiti scattered across the city urging Serbia to reclaim Kosovo, epitomizes the lingering grievances many Serbs still feel—and that the government continues to weaponize—three decades after the country suffered major military defeats and territorial losses in the Yugoslav wars. The former Serbian region Kosovo unilaterally declared independence in 2008.

Some Russian emigres I spoke with, who arrived here after their country launched its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, quipped that present-day Serbia may offer a glimpse of Russia’s future if it fails to defeat Ukraine: a society still harboring ressentiment over lost glories, stemming from a failure to come to terms with a bloody conflict and the international community’s accusations of war crimes.

Despite few cultural similarities and a geographic distance of 1,400 miles between their capitals, Russia occupies a unique role in the imagination of many Serbs as the Slavic “big brother” nation, a grand empire asserting Orthodox Christian values against the West in a global standoff.

These lands have a long tradition of hosting Russians fleeing sociopolitical turmoil and repression at home. Following the 1917 Russian Revolution and subsequent Civil War, tens of thousands of Russian clergy and nobility fled the Bolsheviks to what was then the capital of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

For the estimated 150,000 to 300,000 emigres who have arrived in Serbia since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine—some escaping wartime censorship and mobilization, others worrying that sanctions might cripple their country’s economy—the Serbs’ generally positive attitude toward Russians has made life here more appealing.

Visa-free entry and a simplified process for acquiring residency permits make Serbia an attractive destination for Russians of all stripes, from LGBTQ+ activists to baristas and tech workers whose companies have opened offices here. Some have tried to collaborate with and hire locals and even learn the language, which bears some—although minimal—similarities to Russian.

However, many continue to live in isolated emigre enclaves, working for Russian companies and sending their children to Russian schools. Weak public support for Ukraine and the absence of kind of discourse seen elsewhere that thrusts responsibility for the invasion onto ordinary Russians has created a depoliticized climate for exiles.

Many emigres also trickle in from countries like Kazakhstan, Georgia, Turkey and Uzbekistan, which served as initial havens during the first year of the invasion. But challenging conditions for integration and anti-Russian sentiments in some of those places are rendering them temporary waystations.

Trouble for activists

By contrast, many Russians who have arrived in Serbia envisage themselves planting their roots here—a rare sentiment for a migration largely guided by uncertainty and ambiguity. This sense of permanence may position Serbia as a key destination for Russian emigrants who aren’t seeking political asylum in more stable regions like the European Union and prefer to continue working remotely in the Russian economy.

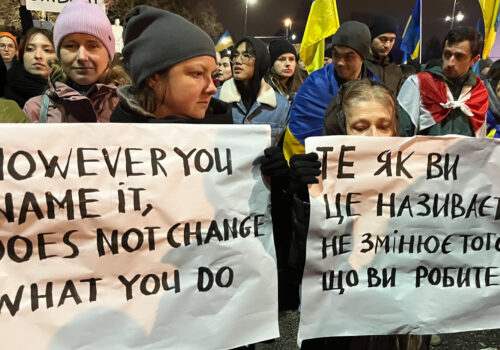

The situation is different for Russian exiles openly engaged in anti-war activism. They have become targets of the Serbian government. Numerous opposition activists, likely flagged for organizing political rallies in support of Ukraine, have been barred from reentering the country or denied residency extensions, fueling speculation that the authorities are acting in coordination with the Russian security services.

In the first weeks of the invasion, realizing that thousands of his former compatriots would be arriving in the country where he had already been living for several years, one such activist and dual Russian-Dutch citizen named Peter Nikitin began developing a political organization to represent anti-war Russians in Serbia.

From the spring of 2022 until its recent dissolution, the Russian Democratic Society was a registered NGO with a space to host lectures and discussions as well as volunteers to organize rallies and donation drives to support Ukraine and Russian political prisoners.

But over the past year, Nikitin explained by phone, several members have been barred from reentering Serbia or were not granted residency extensions on the vague grounds that they “posed a threat to the stability and security of Serbia.”

One of Nikitin’s fellow activists who organized concerts featuring musicians labeled “foreign agents” by Russia was ordered to leave the country. Another Russian family has been refused residency extensions, Nikitin said, as punishment for hosting a Ukrainian refugee.

“Such decisions contradict the Serbian constitution, which requires the government to explain specifically why it is denying a residence permit extension,” Nikitin told me in adidactic tone that suggested he was thoroughly versed in Serbian rule of law.

One of the most egregious cases was that of a 19-year-old activist named Ilya Zernov, who was stalked and assaulted by a group of far-right vigilantes after he had painted over a mural that read “Death to Ukraine.” He fled the country for Germany on humanitarian grounds, but when he tried to renter Serbia for a scheduled court date, the Serbian authorities barred him.

Nikitin and his colleagues have tried to challenge those decisions in court, even galvanizing locals to sign petitions, but mostly to no avail. He explained the authorities’ behavior as a symptom of the decision by Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić to “sit on two chairs,” pursuing a position of neutrality by appearing amicable to the West while not angering Russia

The impression that Serbia has been pursuing an entirely pro-Russian stance was diminished last year when the Financial Times revealed that Belgrade was sending military aid to Ukraine. While the country has refused to comply with Western sanctions against Moscow—one reason so many Russians have registered businesses and opened bank accounts here—it did join Western countries in its condemnation of the invasion.

“The government leans on pro-Russian, anti-Western propaganda as a populist tool to gain popular support,” Nikitin said.

The fraught climate has made Serbia a dangerous place for activists, Nikitin added.

“Russians with [politically motivated] criminal cases opened against them should not come here—there are few perspectives for the political diaspora,” he told me.

At one point, far-right Serbian outlets launched a disinformation campaign against Nikitin, alleging that he was using “Western grant money” to purchase drugs, for his own psychological treatment and queer orgies.

When I asked how he felt about non-political emigres such as the IT specialists who comprise a large fraction of the diaspora here, Nikitin said that while many may not publicly show their opposition for the war, some are among the largest donors to organizations helping Russian political prisoners and Ukrainian refugees.

In any case, with rumors swirling that the government may reduce the required waiting period for residents to obtain citizenship—likely to accommodate the tens of thousands of Russian migrants—the conditions for legal integration continue to make Serbia an attractive destination for nonpolitical emigrants to a country that welcomes their contribution to the economy.

The Yandexoids

Russian emigres have coined a new colloquialism for a specific cohort of their compatriots. “Yandexoids”—employees of Russia’s major tech giant Yandex—who are commonly in their mid-to-late 20s and early 30s, and can be spotted at their laptops in cafes across the city’s old town. The company is referred to as both Russia’s Amazon and Google, which provides the country’s main search engine as well as ride-share taxis and a slew of other services. The central office here is in a sleek black building with a rooftop terrace that peers over the Danube River on one side and the Belgrade fortress on the other.

Each floor features a modern café as well as rounded, sound-proof pods where employees can take calls, ping-pong tables and strangely shaped furniture with spinning capabilities. In short, all the typical amenities meant to optimize productivity and increase worker satisfaction.

It seems to be working. One employee told me on condition of anonymity that 85 percent of the company’s Serbian wing staff indicated in surveys that their current mood and psychological state is “great.” Considering that they recently left behind their home country—which is waging a full-scale war against its neighbor, conscripting civilians and incarcerating opponents of the regime—that is quite a feat.

Elsewhere, my observations in various countries indicate that many emigres—troubled by uncertainty, the challenges of having to abruptly move to new countries and an increasingly pessimistic news cycle of death and destruction in Ukraine and repression back home—have significantly increased their reliance on anti-depressants, therapy and alcohol.

The company underwent a transformational split after the war, breaking into domestic and international branches; the Belgrade office belongs to the Russian branch. Desperate to retain the large portion of its workforce, it splurged on two offices here.

Although all signs in the main building are written in Serbian and English to comply with protocols required of all companies registered here, only about 60 Serbs—excluding security guards and cleaners—are among the workforce of roughly 1,900.

Another striking feature is that about 70 percent of employees are men—who largely fled military mobilization. “When I visit our offices back in Russia, I only see dolled up girls and a few gargoyle-like men,” my source quipped.

In accordance with corporate policy, the Yandex offices are politics-free. While the employee I spoke to told me she had fled Russia because of her political convictions, she could not say the same of her coworkers. Occasionally, she said, slurs directed at Ukrainians appear in anonymous company chats, quickly met with a torrent of “thumbs down” emojis.

Stepping out into the streets of Belgrade through the sliding doors of what is perhaps the city’s most modern corporate office—staffed primarily by ordinary Russians—is a strange experience. Picture a Google office in Peru staffed exclusively by Americans.

The company is just one of roughly 9,500 Russian businesses registered in Serbia since the start of the war, according to a recent Deutsche Welle report. Novi Sad, a small suburb of Belgrade, is home to several of them, as well as hundreds of young Russian families. Emigres have opened Russian-language preschools, further emphasizing how they live in a “parallel reality,” the report notes.

A descendant of White emigres

But some—particularly in the culture and service sectors—have made it their mission to integrate, learning the language and opening businesses that attract locals. Many Russian-owned coffee shops and bars now dot the city center, with menus in Serbian and English, where delighted locals can be found sipping vodka infusions and occasionally toasting “our Russian brothers.”

Andrei, a tall, young and handsome aspiring actor, is a local who pours organic Balkan and imported wines at Process, a Russian-owned bar. The owner, a St. Petersburg native and former event organizer named Grigory Vlasik, is the “ideal model” of a Russian emigre in his approach to integration, Andrei said. Vlasik has been learning Serbian and says he has watched perhaps every Serbian art-house film ever made. “I really respect that kind of an effort,” Andrei said. “It makes us much closer, and if more Russians try this, it will make integration easier.”

With roughly 6.6 million inhabitants, Serbia is largely a monoethnic country, and Russians form a sizable diaspora. Locals notice Russians who refuse to learn the language, forget to tip waiters and order in Russian, Andrei said.

“My friends often complain to me about these types,” he said, “especially since their arrival sort of gentrified the downtown and caused rents to skyrocket.”

Andrei had a personal connection to Russia even before starting at Process. His great-grandfather, a former doctor in the Russian Empire, was among the many aristocratic emigres who came to Serbia after the Bolsheviks took power. Like many from the former aristocracy, he experienced drastic downward mobility, eventually finding work in a railway ticket office.

Suffering from PTSD brought on by the horrors he witnessed during the Russian Civil War, he slipped into alcoholism, Andrei said, recalling family stories. He would stew over lost glories, drunkenly belting out songs about the Russian Empire while clutching a portrait of Emperor Nicholas II as Serbian police arrived to detain him.

After Communist leader Josip Tito came to power in Yugoslavia after World War II, his spat with Soviet dictator Josef Stalin significantly worsened conditions for Russian emigres—in the form of repressions—spurring a mass exodus. Those who remained were forced to assimilate, avoided speaking Russian altogether and passing the language on to their children.

Despite his ancestry, Andrei has to learn Russian as a second language in order to speak it, which he is now doing through his job. He hopes that despite the war and domestic repressions in Russia, knowing Russian will increase his chances of pursuing an acting career there one day.

Rock-n-roll and black coffee

The warmth with which today’s Russian emigres have been welcomed in Serbia has created opportunities for cross-cultural collaboration. Stepan Kazaryan, a concert promoter from Moscow, is organizing Changeover—a music festival featuring Russian, Serbian, European and even American performers—for its third consecutive year in Novi Sad.

Kazaryan came to Belgrade in March 2022, already familiar with the Serbian underground-music scene and seeing potential for its evolution.

A few weeks before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he was asked by a member of the Moscow city administration to remove the Russian dissident rapper Oxxxymiron—now a designated a “foreign agent”—from a festival scheduled to take place that summer. When Kazaryan tried to push back, officials quipped that he might as well comply now, as he’d “be cancelling the festival anyway soon enough.”

“I knew then that something very drastic was on the horizon,” he told me in his deep, hoarse voice, downing his third Serbian rakia outside a neighborhood bar where the bartenders knew him by name.

For several years before the war, Kazaryan was responsible for organizing Bol—the largest underground music festival in the Russia and a platform that had launched the careers of many bands from the country’s far-flung regions. Having studied political science at university, he attributed his foray into music to two specific experiences. The first was his earliest childhood memory, when he attended a concert in Copenhagen by the iconic Soviet rock band Kino with his father, a Soviet diplomat.

It was 1989, and Kino was the only Soviet band in a lineup of European artists performing to raise money for victims of a major earthquake in Armenia. “Back then, everyone was eager to engage with our culture,” he said of the period leading up to the collapse of the Soviet Union. “It was very a different time.”

Later, while completing a Master’s program at Le Salle University in Philadelphia, he spent several months living in what he called a “punk, vegan squat.” Mesmerized by America’s underground-music scene, he became determined to promote something similar in Russia.

Kazaryan’s prominence back in Russia meant he would eventually fall under the crosshairs of Ukrainian activists seeking to culturally isolate Russians abroad. For the third year in a row, Changeover’s headline artists—American and European—have withdrawn at the last minute after receiving letters from Ukrainian activists urging them not to participate in an event organized by an “enabler of war.”

“I think the fact that I shut down Bol in Russia, lost thousands of dollars in the process, publicly denounced the invasion and left my country just a few days after the invasion should be evidence enough that I am no enabler,” he told me.

He has also broken relations with his mother, who once called to mock him after reading an article by the pro-regime theater director Konstantin Bogamolov in which he refers to the current crop of emigres as victims of a “psychological epidemic.”

“Oh, how Bogamolov dragged you guys through the dirt!” Kazaryan recalled his mother as gloating.

Still, he says he’s grateful to be able to continue the work he loves in Serbia. He considers the festival a “gift” for a country that took him in at a difficult time and a way of bringing visibility to Serbian music.

Cherniy Cooperative Coffee Roasters—an iconic coffee shop in Serbia’s old town that was once a hub for activists, artists and tech workers in Moscow—has been transplanted from the Russian capital’s Chistiye Prudy neighborhood. Its founder Artemy Temirov, a pro-Ukrainian leftist, now primarily lives in Athens with asylum status with his Ukrainian wife, who works for a non-profit aiding her compatriots in their defense against Russia. He frequently visits Tbilisi and Belgrade, where he opened new locations for Cherniy after selling his share of the Moscow branch. In the long term, he plans to rebrand and expand the project into the European market, confident that its high-quality coffee and unique aesthetic can compete.

Before the war, Temirov hosted fundraisers at Cherniy—initially registered as a “cooperative” and operating under the principles of horizontal work structures—for NGOs supporting Russian political prisoners. The activism put the establishment on the radar of the Moscow authorities, leading to multiple raids on the premesis.

Despite his open political stance, Temirov says he regrets he was part of a generation that wanted to live “under the illusion that Moscow was ‘the greatest city on earth’ with relative freedoms, and that even [Cherniy] was part of its decoration.” He spoke outside the Belgrade iteration of the coffee shop, a cap covering his shaved head.

Temirov and his wife greeted the invasion on opposite sides of the front—he was in Moscow, and she in Kyiv. They first met in Belgrade soon after and eventually moved to Greece after being granted asylum. Far from the waves of Russian emigres, his wife can calmly continue her work there.

Temirov takes issue with the political apathy displayed by many of his compatriots in Belgrade. “Arriving in Belgrade, you end up in a large Park of Culture,” he said, referring to the official designation of Moscow’s Gorky Park, which has become synonymous with the apolitical, materialistic comfort of Muscovites in recent years. “It’s one thing to refuse to raise money for the Ukrainian armed forces,” he added, but emigres in Belgrade “could at least host events to support Russian political prisoners—and I seldom see this here.”

“Belgrade is a city where emigres can live a comfortable and privileged life and not think about Ukrainians or the repressions back home,” he said, adding that that attitude played a role in his family’s decision to live in Athens.

LGBTQ+ exiles in Belgrade

Over the last two decades, St. Petersburg’s central Nekrasov Street was the “bar row” for the Russian intelligentsia, where celebrities like the author Vladimir Sorokin could occasionally be spotted downing whiskeys in one of the many watering holes lining the Baroque street.

On the outskirts of Belgrade’s city center, emigres from the northern Russian city opened a bar as homage to the street. More than a welcoming watering hole for locals and emigres of all stripes, Nekrasova Bar is also a hub for Russian LGBTQ+ exiles and activists.

None of the members of this community with whom I spoke left Russia in the immediate aftermath of the invasion. They arrived in Serbia much later than their more privileged compatriots for various reasons.

In the back of the bar, some of the activists set up a “library”—a project they refer to as “Shelf Community”—for emigres longing for the books they left behind. Visitors can rent books for extended periods using a QR code.

The two organizers of Shelf Community were both editors at independent Russian publications that published queer literature alongside a wide range of progressive domestic and international, translated works.

They initially had to remain in Russia due to a lack of resources, but when censorship, especially against LGBTQ+ material, intensified, they realized that continuing in the industry was no longer sustainable. “We’d publish work with nearly half the text blotted out to comply with censorship,” one organizer told me, describing a practice reminiscent of the most draconian periods of Soviet authoritarianism.

She described being forced to remove an entire chapter from a translated German book on breathing self-help practices because it alluded to BDSM.

It was also a matter of resources for Michelle, a 34-year-old trans bartender at Nekrasova. Behind a screen of cigarette smoke in the kitchen of his crammed basement apartment, he told me how his parents—both low-income artists—saved up for his departure. He was still in Russia in November 2023 when the government added the “international LGBTQ movement” to its list of designated extremists. “We got together with our friends that day and ironically cheered that we were now ‘extremists,’” he told me.

Amid Russia’s swing toward so-called “traditional values” in recent years, resources for transitioning have been restricted, and medical professionals who assist in such procedures can now face “extremism” charges. But in the safety of Serbia—where discrimination based on sexual orientation is illegal—he now has access to the resources necessary to complete his transition.

Michelle’s roommate, a queer-rights activist who asked to be called Lin, also stayed in Russia until the “extremist” law was passed because she felt it necessary to support a vulnerable group at a perilous time. Until her departure and the dissolution of the organization where she worked, she compiled cases of repression against LGBTQ+ community members to send to the European Court of Human Rights.

While Lin is grateful she can safely breathe in Belgrade—a city where the local LGBTQ+ community has welcomed its Russian counterparts—her inability to help those in need at home has left her feeling “helpless and guilty.”

Russian officials “perceive LGBTQ+ as some sort of political movement, which is completely absurd,” she said.

When I asked if she would consider returning to Russia if the war ended and circumstances changed, Lin said she would certainly not return in the “immediate future.”

“The new class of ‘vulnerable’ will be men with lost limbs and PTSD who will require prosthetics and therapy and who will be aggressive and make our cities unsafe. This is a process I want no part of,” she asserted.

Michelle and Lin recently attended a Belgrade Pride festival for the first time in their lives. Serbia is a relatively conservative society, so such events are not immune from aggression. One local approached Michelle and tore off his rainbow flag.

“This was nothing compared to Russia,” Michelle said stoically. “There, if I stepped out onto the streets with such a flag, I know for sure I would wake up in a hospital or in a jail cell.”

While Serbia is far from an ideal democracy—with recent reports highlighting how the government relies on anti-Western conspiracies to discredit its opposition and cozies up to Russia—Russian economic migrants, and even vulnerable groups like the LGBTQ+ diaspora, continue to perceive it as a comfortable long-term home.

The situation is far more precarious for politically outspoken migrants. In the coming days, the fate of a Belarusian dissident filmmaker arrested in Serbia at Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko’s request, will be determined. If he is extradited, it may mark a dark turning point for exiles fleeing both Putin’s and Lukashenko’s regimes.

Top photo: The LGBTQ+-friendly Neraskova Bar in Belgrade, opened by Russian exiles as an homage to St. Petersburg